If you saw a rainbow flag flying from a building, you might naturally assume that it housed something LGBT related or its residents wanted to show their solidarity with LGBT people. But if seeing a rainbow in the sky leads you to think of the LGBT community, then perhaps something isn’t quite right with you.

Leonid Gozman

Russian opposition politician

Similarly, the Ukrainian flag, naturally, invokes Ukraine. But if someone wearing a combination of blue and yellow clothing is sufficient for you to denounce them for sympathising with an enemy power, then surely something is wrong.

As well as rainbows and random sartorial combinations of blue and yellow, the Russian authorities have identified yet another cause for concern in the form of the traditional May Day slogan “Peace, Labour and May”, its reference to peace being patently too dangerous to go unchallenged in wartime Russia.

Discarded “Peace, Labour and May” signs. Photo: Dmitry Tsyganov

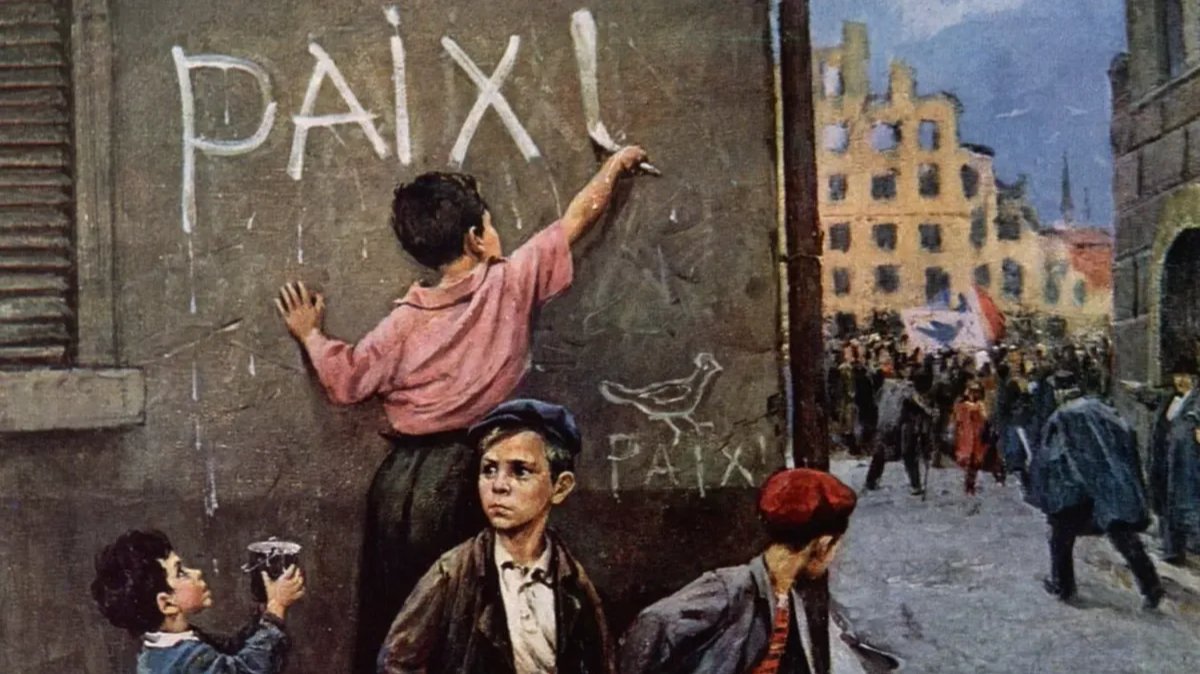

Removing the word “peace”, alongside its extremist connotations, is troubling, and the level of insanity marked by this development is upsetting. Fyodor Reshetnikov’s 1950 painting For Peace!, in which four Parisian children hiding from the police write the word “peace” on a wall, feels very much like a portrait of our times.

The charge to ban the word “peace”, or to make using the word “war” a criminal offence, seems, at first glance, to be led by nothing but extraordinary stupidity; but beneath the surface, there are explanations. One could be that the authorities do not understand that slogans are largely meaningless. “Peace, Labour and May” is simply a marker for the May Day holidays. “Peace to the World” means that everything should be good and not bad, but has nothing to do with any ongoing wars.

Yet particular words, which in the context of these familiar formulas mean nothing at all, do cause Russian officials disquiet.

This might be because they take their own statements very seriously, and therefore assume the same for their subjects, which is quite natural, if you imagine that 90% of the population hasn’t been paying attention to what they say for a long time.

Their actions are indicative of a fear felt within the government. A fear for the crimes committed in Ukraine, yes, but also a fear for everything else. They are seemingly even afraid of us! They have everything, we have nothing, yet they are the ones who are afraid.

Case in point: The State Duma committee on something or other has just approved a ban on “foreign agents” running for any kind of office in Russia at all. This new bill was drawn up in response to opposition politician Elvira Vikhareva’s plan to nominate foreign agents to stand in all 35 districts in next month’s Moscow municipal elections. Their chances of winning were always going to be rather slim, but judging by the hysterical reaction of the authorities, the stunt was a success.

But it is not only in the context of elections that they fear their opponents. Why else would the courts so relentlessly try cases for libel, terrorism and so on in absentia? They serve mainly to ensure that those convicted of crimes won’t return to Russia.

Do you wish to take revenge, to settle scores? Or are you afraid we’ll be there to take the Kremlin by force? Either answer paints you in a poor light.

I learnt many years ago that according to military strategy, anti-tank guns should be placed in areas where a tank could be dangerous. That is, defences should be placed in the areas where an attack could be deadly.

So the military digs trenches and converts basements into bomb shelters to protect themselves from an attack by Ukrainians. But when this is happening all the way to Siberia, can we really say that the “special military operation” is going well?

And where else is vulnerable? Where else could an attack prove deadly? Why everywhere! And to ramp up control at home, they entice soldiers back from the war by offering them political office. Elected to various levels of the Russian Duma, and in some cases the executive branch, they are, in Putin’s words, the “new elite”.

They don’t demonstrate loyalty to any particular leader or idea. The motives and circumstances that prompted their arrival on the frontline are varied, but patriotism is unlikely to have been their sole motivation. Despite this, they do have something which, according to the authorities, bureaucrats promoted in peacetime appear to lack — a willingness to use force and to disregard the law.

The new elite, armed with the logic of war and their first hand experience at the front, will promote a policy of unclouded violence from their new governmental positions. When the law doesn’t work for them, they will bribe, intimidate and use physical force, while taking care to build defences against any kind of dissent.

As the Russian state adopts ever more totalitarian policies, it’s worth remembering that their actions are motivated by fear, and, believing themselves to be vulnerable, they are bracing themselves for an attack.

They are afraid because they are aware of their own weakness, both on the frontline and at home. They are more aware of their own weakness than we are, and that’s good news on the whole.

Views expressed in opinion pieces do not necessarily reflect the position of Novaya Gazeta Europe.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]