Last month’s terror attack on Moscow’s Crocus City Hall and the subsequent detention of a dozen citizens of Tajikistan has been bad news for Central Asian migrants to Russia, who are already subjected to routine discrimination and harassment from the police.

But it also led to soul searching of various kinds, particularly with regards to how Muslim migrants are treated in Russia, and the stark differences that exist between Russia’s well-integrated indigenous Muslim communities in regions such as Tatarstan, Bashkortostan and the North Caucasus, and its more recent — and frequently temporary — Muslim immigrants from Central Asia.

The Tajik IS

Once they were in police custody following their capture in western Russia’s Bryansk region the morning after the attack, the alleged Crocus City Hall terrorists claimed that they had been recruited via Telegram by an assistant preacher they knew only as Abdullo. This was widely understood to be Abdullo Buriev, a Russian citizen of Tajik origin who is believed to be linked with the Afghan IS cell involved in a terrorist attack on a Catholic Church in Istanbul on 28 January.

It was Islamic State — Khorasan Province, more commonly known as IS-K, that claimed responsibility for the Moscow concert hall attack. Led by Shahab al-Muhajir, a 29-year-old Afghan, it takes its name from Khorasan, “the land of the rising sun” in Persian, a vast historical region of Central Asia that included parts of modern Iran, Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. Unlike a number of other countries, Russia hasn’t yet formally recognised this iteration of IS as a terror organisation. However, the group holds a number of significant grievances against Russia.

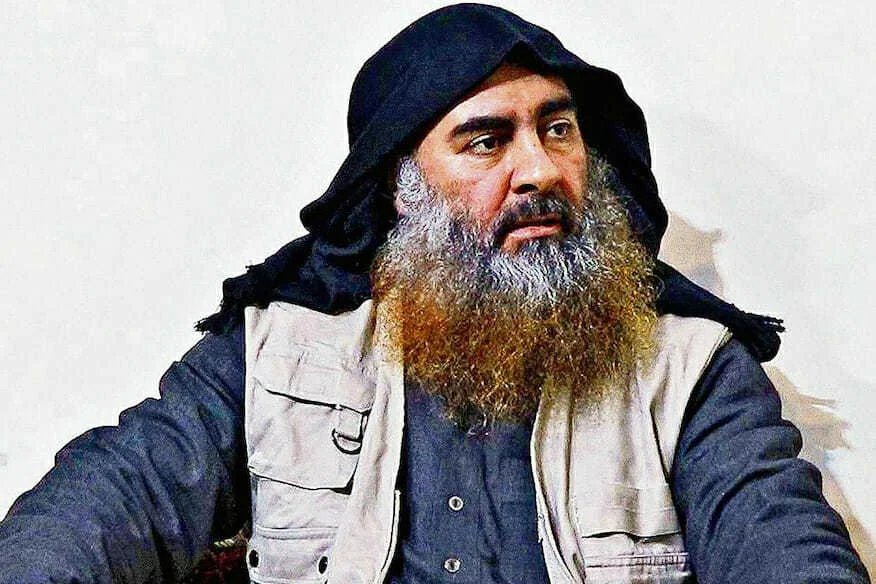

IS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. Photo: US Department of Defense

Between 2010 and 2014, when Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi was world caliph, IS aimed to create global structures and divide the entire Islamic world into a number of “provinces”. From then on, adherents could technically join IS from afar, by swearing an oath of allegiance, to the point where, as many Islamic scholars note, it went from being a territorial quasi-state to an international terrorist “franchise” with no single command centre. In some areas, such as Afghanistan and Pakistan, there are several competing IS cells operating at once, but in post-Soviet Central Asia, the most visible is IS-K, whose missionaries speak Tajik and actively preach online.

Like many radical Islamist groups, IS-K sees the Taliban as opportunistic, not least for its ties with “godless” Russia, and is in general extremely hostile to the group, which returned to power in Afghanistan in 2021. IS-K had already clashed with Russia in Afghanistan, with the group claiming responsibility for an explosion at the Russian Embassy in Kabul on 5 September 2022, in which two employees were killed.

IS-K also considers Russia’s two closest allies in the Middle East, Syria and Iran, its sworn enemies, and bombed a cemetery in the Iranian city of Kerman as recently as January, killing at least 94 people. Iran’s desire to spread Shia Islam around the world, which the Sunni Salafists of IS see as something akin to paganism, only adds to the group’s contempt for Tehran.

Money plays a central role in recruiting Tajiks to IS. In 2015, according to a UN study, almost a third of Tajikistan’s population was living in extreme poverty. The national population also rose sharply in the post-Soviet era, from 5 million to 9 million, and youth unemployment currently stands at over 20%. With this in mind, it becomes rather easier to understand why joining IS-K might appeal as a career move.

Orthodox jihad

In the words of Sayyid Qutb, one of the chief ideologues of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, humanity faces moral, and then physical death, due to its abandonment of spiritual values in favour of pursuing technology and material comfort instead. In order to guide humanity back to its true path, he argued, a renaissance of religious faith and a return to traditional ways of life lived in accordance with that faith was necessary. It’s perhaps unsurprising that such rhetoric struck a chord with Patriarch Kirill, who so hates the “post-Christian” West, has increasingly been singing the praises of the Islamic world in recent years.

“Our President Vladimir Putin … once told a journalist who asked a question about the relationship between Orthodoxy, Catholicism and Islam, ‘We are closer to Islam’. I agree… The West lacks even basic morality.”

Armed police officers carry out checks on Moscow’s Red Square following the Crocus City Hall attack, 27 March 2024. Photo: YURI KOCHETKOV / EPA-EFE

IS tried to practise what it preached in the areas of Iraq and Syria that came under its control in the early 2010s. Sergey Golunov, a doctor of political science at the Russian Academy of Sciences, said in a 2020 article that the caliphate “openly challenged the [international] community, encroaching on the inviolability of state borders, … explicitly ignoring generally accepted humanitarian norms”. Like the “special military operation”, the caliphate claimed to put an end to “the Westphalian system of international relations”, and required a permanent state of war to underwrite its existence.

Contradictory attitudes

According to some estimates, there are as many as 4 million Muslims living in Moscow, giving the city one of the largest Muslim populations of any city in Europe. Indeed, police statistics show that there are now more practising Muslims than practising Orthodox Christians in the Russian capital.

Guest workers from Tajikistan, whom the Russian authorities view purely as cheap labour and do nothing to help support or integrate, remain one of the most marginalised communities in the country and are frequent victims of xenophobia. Their difficulty integrating into Russia’s Muslim community has made them easy prey for global Islamist movements.

Policemen checking people at Red Square amid heightened security after the terrorist attack at Crocus City Hall, 27 March 2024. Photo: Yuri Kochetkov / EPA-EFE

Hand in hand with his new found fondness for Islam, Patriarch Kirill has also begun actively criticising Russia’s current migration policy. Claiming that migrant workers terrorise the local population, the patriarch has called for severe restrictions on the number of migrant guest workers entering the country, cautioning that otherwise “we will lose ourselves, we will lose Russia”.

At a specially convened emergency meeting last week of the World Russian People’s Council (WRPC) — an organisation that describes itself as a forum for those who share “concern over the present and future of Russia” — the patriarch surprised everyone by declaring: “Nobody should be scaring citizens with the idea of Russian nationalism. Russian nationalism doesn’t exist.”

In response to the terrorist attack, oligarch Konstantin Malofeyev, Patriarch Kirill’s long-time deputy at WRPC and owner of the ultranationalist pro-Kremlin Tsargrad TV channel, announced the launch of a special fund to “promote legislative initiatives” aimed at restricting migration. The patriarch even saw fit to grant Malofeyev’s request to step down as his deputy to allow him to focus all his energies on such a noble cause.

Muslims during morning prayers to celebrate Eid al-Adha outside Moscow’s Sobornaya Mosque, 9 July 2022. Photo: EPA-EFE/YURI KOCHETKOV

Given the level of obsession with Ukraine visible in the upper echelons of the Russian government and in the propaganda that serves it, it would be strange to expect a responsible and transparent inquiry into the events leading up to Crocus City Hall. Official reports sport multiple inconsistencies, and some important details are omitted completely. Nevertheless, the Islamist version remains the most consistent and plausible.

The Kremlin’s refusal to co-operate with international structures designed to combat terrorism and its inability to see beyond Ukraine make ordinary Russians even more vulnerable and ever less protected. The potential consequences of this for migrant workers in Russia, who are now seen as a legitimate target for the mob, is too dreadful to consider.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]