The belief that masculinity can be accentuated through acts of violence is just one of the patriarchal attitudes that reigns supreme in Russian society, but it also serves as a very convenient tool for military propagandists with an interest in driving recruitment and stifling the growing anti-war sentiment in the country.

A recent illustration of this was seen in January, when the wives of mobilised Russian soldiers paid a visit to Vladimir Putin’s Moscow campaign office to demand their husbands’ return from the front after more than a year away from home. The activists were told in all seriousness by a female member of staff that being sent home now before they could reach their objectives would only serve to “humiliate” them.

This discourse, which has gained traction in Russian society for generations, is especially useful for the authorities during wartime, as it provides an excuse to silence women who dare interfere in “men’s matters”. Even trying to prevent the death of a husband or son can therefore be framed as an assault on their male dignity.

Masculinity, referring to the practices and beliefs that define what is considered “a real man” in a social context, is far from a new concept, and its idealisation of a certain form of manhood remains a pillar of the Putin regime. Russia benefits from hegemonic masculinity, a system designed to ensure that power remains in the hands of a certain minority of men who represent a masculine ideal — in this case, Vladimir Putin.

“Putin would not have invaded Ukraine if he were a woman,”

former UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson said in June 2022, blaming the Russian invasion of Ukraine on “toxic masculinity”.

A couple of days later, the Russian Foreign Ministry summoned the British ambassador to protest what it called Johnson’s “frankly boorish” statements, which it said were intended to undermine “Russia, its leader and the Russian people”.

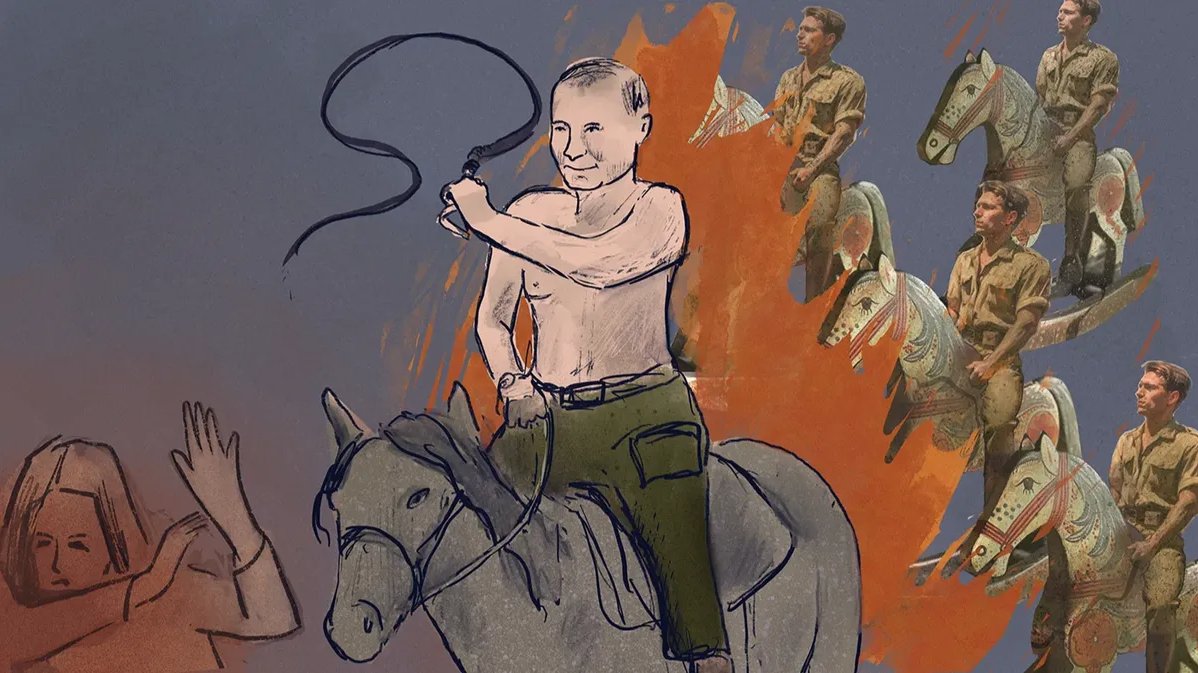

Putin has expended much time burnishing his “alpha male” image, which is likely the reason Russian diplomats were so quick to take offence at Johnson’s comment. The infamous photographs of Putin horse riding bare-chested, his hunting trips with Defence Minister Sergey Shoigu, and his annual dips into ice-cold water were all part of a years-long campaign to enhance this strongman image.

Despite his personal life being shrouded in mystery and strictly off limits to the Russian media, efforts were made to portray Putin as a “sex symbol”, too, especially during his earlier terms, exemplified by novelty pop song Someone like Putin, which was used by Putin’s team for his 2004 election campaign, the main lyric of which is “I want a man like Putin, who’s full of strength.”

The SUPERPUTIN exhibition at the Ultra Modern Art Museum (UMAM) in Moscow, Russia, December 2017. Photo: EPA-EFE/MAXIM SHIPENKOV

Throughout his time in power, Putin has sought to reinforce his macho image by making chauvinistic statements presented as jokes. “A real man must always try, and a real woman must resist,” he famously said at a press conference in 2004, quoting a line from a 1960s Italian film to describe the relationship between journalists and the government. Two years later, Putin reacted to the news of Israeli President Moshe Katsav being accused of raping and sexually harassing 10 women with praise: “He turned out to be a very powerful man, raping 10 women! He surprised us, we all envy him.”

The crude remarks seem to have reached their crescendo shortly before the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, when Putin quoted a Russian punk rock song describing a rape to illustrate Russia’s demands from Ukraine: “Like it or not my beauty, put up with it you must.”

Reinforcing stereotypical masculine attitudes has become a staple of Russian state propaganda since the war began, with the idea that military service is “what real men do” being inculcated in the population, all the while carefully omitting the fact that Putin himself has never served in the military.

Adverts for enlisting in the military promise Russian men they’ll return home as heroes, while earning enormous sums of money to boot. More often than not, it tends to be men from less well-off backgrounds who enlist in the military, hoping to become a traditional masculine archetype, the kind of desirable, well-off man it’s impossible for them to be in their ordinary life, according to psychologist Vlad Krivoshchekov.

The image of men as “defenders of the fatherland” is nurtured from an early age, as Russian schools and kindergartens hold annual military-themed celebrations, dressing up boys in military uniforms.

“A role model is created for a young boy — even if he doesn’t aspire to be in the military, he can’t completely abandon the idea,” psychologist Sofya Goldman explains, adding that the patriarchal upbringing of boys is to blame for adult men not taking the brutality of war seriously.

“The horrors of war are glossed over. Instead, a picture is presented of a hero who comes home with victory to a loving family. War seems like a child’s game in which you win.”

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]