Police officers walk past an illuminated letter Z in support of the Russian army near the Kremlin, 25 March 2023. Photo: EPA-EFE / YURI KOCHETKOV

Over two years have passed since the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, and despite the situation for the country’s fragmented political opposition looking bleak, with the exile, imprisonment or murder of all leading Kremlin critics and the threat of long jail sentences brandished at every turn to silence dissent, beneath the surface a different story unfolds.

From the quiet defiance of green ribbons and online gatherings to a burgeoning network of underground workshops and printing houses, a decentralised civil resistance movement is quietly taking root in Russia. This movement, fuelled by a belief in a free future, provides a crucial counterpoint to the prevailing Kremlin narrative and attracts those who want to remain in Russia and fight for change from within.

Amid whirring 3D printers and the glow of computer screens in a Moscow coworking space, a camera offers me a glimpse of the bustling workspace in the background as a young woman welcomes me to one of these groups’ “little shelter”. She assures me that while they may look like a ragtag lot, their actions — that run from organising lectures to engaging in cyber espionage — are driven by one common goal: empowering others to fight for a better future.

The group operates in anonymity, embracing the collective power and safety it affords. Nevertheless, their work is fraught with risk. Just weeks ago, one of their members was arrested for funding an “extremist organisation”. While they were eventually released, the timing amid a huge surge in accusations against anyone engaged in any form of political opposition was poor and followed a disturbing trend that predates the war.

Hacking into official email accounts and disrupting government workflow would be dangerous enough anywhere, but it’s especially so in Russia during wartime. However, as one of the group’s members explains, you stand a far higher chance of success if you fight from inside the country. Few in the group would even consider leaving Russia, fuelled, they say, by a deep love for their homeland and a desire to challenge the state’s oppressive policies.

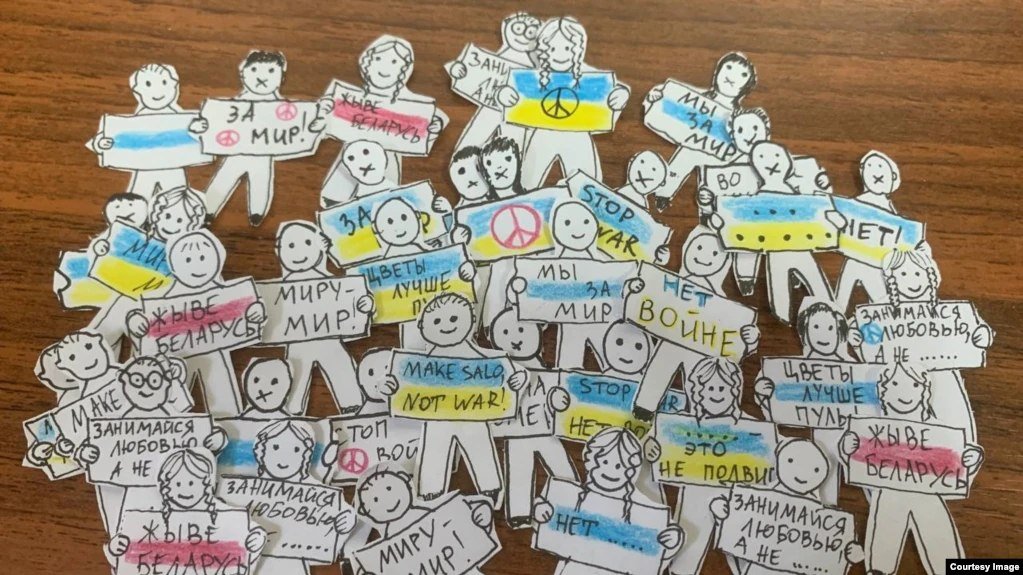

Anti-war group flyers. Photo: Feminist Anti-War Resistance Group

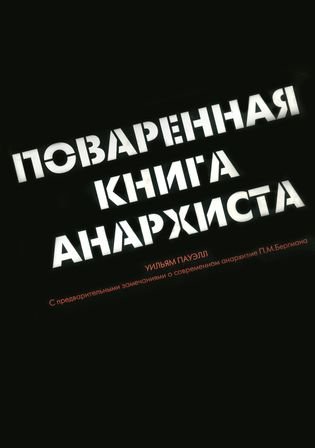

In the heart of St. Petersburg, a hidden printing press spits out forbidden texts in a rhythmic clatter. The titles of the 21st century samizdats being bound here include Prisma Queer, The Moscow Times, Feminist Anti-War Resistance leaflets and the legendary Anarchist Cookbook. Though chaos might seem to reign, it’s a meticulously orchestrated process.

“It’s never been smooth sailing for us,” admits Maria, a printing press operator.

“Even before the war there was literature, like queer books and stories by foreign agents, that no printing house would publish or even consider printing, so we often had to come to the rescue.”

While their printing and publishing house is not unique, it is one of the few remaining solely analogue underground publishers, and they clearly enjoy embracing old-school resistance methods.

Faced with Russia becoming ringfenced from the outside world by a Chinese-style great firewall scenario, the hope is that the printed materials they produce will lend themselves to a vital alternative means of distributing information.

Maria says that since the war began the publishing house has been forced to adopt extreme security measures, including multiple failsafes, such as shredders and metal barrels filled with petrol, should they be found. They’ve even taken the extra step of completely disassociating themselves from any published works, prioritising the survival of the literature itself and future editions in case distribution gets choked off.

“We cherish the trust the authors are putting in us … and so we’ll strive to keep this work alive for as long as possible,” Maria says.

Following a trend that predates the foundation of the Russian Federation, university resistance movements persist, but their fight for survival has become an uphill battle as the state tightens its grip on both universities and the broader student movement.

Yegor, a young activist at one of Russia’s top three universities, participates in one of the many active anarchist groups. While some call him “a lecturer”, Yegor dedicates his free time to engaging with other students on anarchist ideas, sharing practical approaches for change, and offering a discussion platform for students seeking a space to share their opinions and find those sympathetic to their work.

“It’s much easier than it seems at first. Sure, there are risks, plenty of them actually. But despite our actions being actively persecuted, they are quite simple to carry out. We’re actively using university resources like classrooms and digital tools without them knowing, reclaiming them in a way. We’re taking advantage of everything the state offers, again, without their knowledge”, Yegor says.

Cover of the Russian edition of Anarchist Cookbook. Photo: Wikimedia

“However, things are getting tougher. The war has scared some people into silence, while others who used to protest have become more radical, demanding immediate change and action. I try to teach the younger generation as well as those who are taking their final-year courses to fight effectively yet safely. Even some tutors and lecturers support our aims, but they can’t openly support us, so they just quietly spread the word about our meetings and the possibility of resistance”.

Increasingly common underground resistance groups offer safe haven to those who want to fight the regime without having to sacrifice their freedom.

The massive signature campaign supporting would-be liberal presidential candidate Boris Nadezhdin, the growing anti-war sentiment among both younger and older Russians, and even the frustrations of those who at one point supported the war — all demonstrate that belief in a “Free Russia” persists and things aren’t quite as hopeless as they may seem. Indeed, amid an ongoing war and looming elections, Yegor believes Navalny’s assassination could serve as “a potential catalyst for change and political unity”.

All the names in this story have been changed for the safety of those who contributed.