For some elderly Jewish residents of eastern Ukraine, 2022 was not the first time in their lives that they were forced to flee their homes. Eight decades after running from the invading German army as children in 1941, some of the same people — by now well into their old age — found themselves fleeing once again, this time from the invading Russian military.

Michael Gold, who edits the Ukrainian Jewish newspaper Hadashot, has been interviewing Jewish refugees since the start of the full-scale Russian invasion for the Exodus 2022 project, which records the testimonies of Ukraine’s Jewish community in the wake of the Russian invasion. Gold chose some of the most moving stories he’s collected for Novaya Europe’s readers.

The stories of Holocaust-survivor refugees from the Russian-Ukrainian war stand out even against the horrific backdrop of the armed conflict, and not only because the youngest of them is well over 80. These are people who, in their declining years, were forced to flee violence unleashed on them by a country whose language and culture they rightfully considered their own.

In June 1941, the image of the enemy was obvious and unambiguous, especially for Jews. But in February 2022, the invaders dressed up their invasion of a neighbouring country as concern for its Russian-speaking population and a need for Ukraine to undergo “denazification”. The reality, however, was starkly different. None of the local Jewish community had ever felt the need to flee mythical “Ukrainian Nazis”, but when the approach of their Russian “liberators” could be felt, they knew it was time to leave.

A second tragedy

“On the day of the Russian invasion, I reproached myself: how could a historian fail to have seen this coming?”

laments Borys Zabarko, a Ukrainian historian and president of the Ukrainian Association of Survivors of Concentration Camps and Ghettos.

His childhood experiences in the Sharhorod ghetto in the Vinnytsia region of western Ukraine remain vivid, and he recalls the hunger, cold and disease he witnessed as a six-year-old boy with terrible clarity. He remembers victims of a typhus epidemic being undressed and their naked corpses piling up, as the frozen ground made it impossible to dig even a mass grave. Children were orphaned and there were multiple suicides. However, the mass executions and death camp deportations that were typical of Jewish ghettos elsewhere in eastern Europe didn’t occur in Romanian-occupied Sharhorod, making it unique.

Borys Zabarko. Photo: Marijan Murat / picture alliance / Getty Images

The war in Ukraine is the second tragedy in the life of 88-year-old Zabarko. He didn’t want to leave Kyiv, but the constant anxiety left his only granddaughter on the verge of a nervous breakdown.

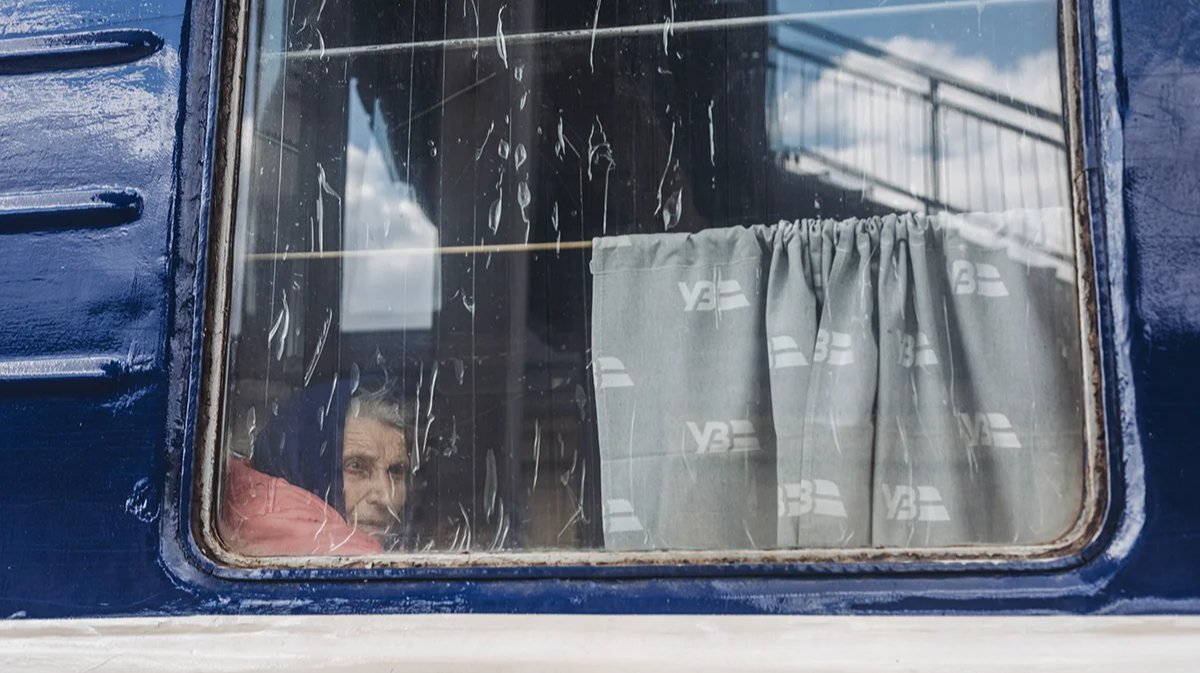

In March 2022, they boarded a crowded train from Kyiv and made their way via Lviv, Uzhhorod and Budapest to Stuttgart. Zabarko is well-known in Germany where his books on the Holocaust have been published, and in 2009 he became only the seventh Ukrainian to be awarded the country’s Order of Merit. Many members of the association he headed have also found refuge in Germany.

Zabarko returned to Kyiv at the start of the year to complete a compilation of recollections written by Jewish Ukrainian Holocaust survivors that he had been working on when he was forced to flee the country.

Promising to survive the war

Not everyone I spoke to is as energetic and mobile as Zabarko, however. When the full-scale Russian invasion began, Ukrainian actor Yevhen Chepurniak’s parents had for years scarcely left their apartment in the city of Dnipro in central Ukraine.

But at 5am on the 24 February 2022, a powerful explosion blew out the windows of the room they were in, stopping their clock as if drawing a line under a past life. No longer a matter of mere evacuation, it became one of outrunning death.

In 1941, his father, Samuil, then 13, fell behind while walking in a column of people the Nazis were taking to be shot. Slipping away, he spent the next 10 months walking to the frontline, eventually arriving in the town of Kizlyar in Dagestan, in the North Caucasus. He lived where he could, warming his feet in manure and drinking water from rivers in which corpses floated.

“Dad has never wanted to buy anything his whole life,” says Chepurniak.

“He always thought you needed to be ready to drop everything and leave. And that’s what happened. We dropped everything and left.”

His father has one prosthetic limb and his mother uses a Zimmer frame. They remained wide awake on the bus all the way to Lviv, despite being given sleeping pills. “I don’t know how they survived. They’re a steely generation,” says the actor, adding that their lives began with an evacuation and were now ending with one too.

Chepurniak’s parents. Photo from personal archive

“Back then, they had their whole lives ahead of them. Now they’ve lived them,” Yevhen reflects. “At such a great age, they should be enjoying their grandchildren and great-grandchildren, not running away from a crazy neighbour.”

But run away they did, from Lviv to Warsaw, and from there to Israel.

“They promised to live until the end of the war, and I promised to bring them home.”

Mistaken for thunder

When 83-year-old Larysa Volovyk left her home in Ukraine’s second city Kharkiv in March 2022, there were two keys on her keyring: one to her apartment and one to Ukraine’s first Holocaust museum, which she founded.

In the autumn of 1941, Larysa and her parents fled their hometown of Bakhmut. A few months later the Nazis walled in the town’s remaining Jews in a tunnel in an alabaster plant. She now has just vague memories of her first evacuation, how her hair froze to an iron rail in a cold train and how they had to boil their clothes upon arrival in Kazakhstan to get rid of lice. On 24 February 2022, Volovyk was awoken by the sound of war, which she says she initially mistook for thunder.

Larysa Volovyk. Photo from personal archive

She and her husband made it onto one of the last buses to the city of Dnipro. From there they travelled to neighbouring Moldova and then on to Israel. She had planned to return to Kharkiv and to the museum where she had worked for 30 years, and managed to record a video for the Exodus 2022 project. Just two days before her unexpected death, we had agreed on a guest list for a private screening. It went ahead anyway, a tribute to the founder of the first Holocaust museum in Ukraine.

‘Not a real evacuation’

As a young man, Pesach Shengait fled to the Urals to escape the Germans. Now aged 99, he has fled to Germany to escape the Russians. In July 1941, the 16-year-old found employment digging trenches near Dnipro in central Ukraine. When the invading German army was closing in, he fled by taking a month-long train ride east, ending up in a tiny village in the Ural mountains, where he found work making tools.

Pesach Shengait. Screenshot

Over 80 years later, he was faced with the same decision whether to stay or go, only now he was 96.

Unlike in 1941, when entire factories were uprooted, equipment and all, leaving Ukraine in 2022 hadn’t felt to Shengait like a real evacuation. But as he could no longer get down to the bomb shelter from his fourth-floor flat, his son — Director of the Kyiv City Jewish community and co-founder of the Exodus 2022 project — decided to take him to Moldova, and from there he went to Germany.

‘Help yourself to some borscht’

Germany is now also home to Svitlana Petrovska, a teacher from Kyiv whose daughter, the well-known writer Katja Petrowskaja, lives in Berlin. Petrovska didn’t just have air-raid sirens to contend with on 24 February 2022, she was attending the funeral of her friend Ivan Dziuba, a literary critic, erstwhile Soviet dissident and Ukraine’s former culture minister.

In early March 2022, Petrovska, whose teaching career spanned 63 years, recorded a video urging her Russian colleagues and other mothers to take action to prevent the war and not to let their sons kill Ukrainians. But as the security situation in Kyiv got worse, her daughter persuaded her to leave, and Petrovska fled to Berlin.

The bus evacuating refugees set off from a synagogue where she met a new mother who had just left hospital with her four-day-old son. The anti-tank traps and checkpoints she saw along the way, coupled with the crying baby, evoked memories of her first evacuation in July 1941. Then, some members of her family had stayed behind in Kyiv and were killed in the Babyn Yar massacres that September.

Svitlana Petrovska. Photo: Katya Libkind / YouTube

Their route constantly changing, they travelled for 26 hours, eventually being told that they were heading to Mukachevo, a city in the far west of the country. As the bus passed through Ukraine, Petrovska’s video appeal went viral. “There were some ridiculous moments,” she recalls. “It was 2am, we had a toilet break, it was freezing, I was on crutches … and suddenly I got a call from The New York Times. ‘Svitlana, we want to interview you.’”

From Budapest, Petrovska took a diversion to visit the site of the prisoner-of-war camp where her father, a Red Army lieutenant, had been imprisoned during the Second World War. Approximately 4,000 Soviet prisoners died there, and it is now the site of a Russian cemetery and memorial.

She then made her way from Vienna to Berlin. “There was a table set for Ukrainian refugees at the train station, but I wasn’t hungry and just passed by when two girls in masks ran up to me,” the woman recalls.

“One of them handed me a bowl, and the second read off a piece of paper, in Ukrainian, ‘Help yourself to some borscht’. And I burst into tears right into the borscht.”

In Germany, she gave interviews, spoke publicly, and opened an exhibition about Ukrainian refugees in Berlin, but by the time she turned 88, she was back in Kyiv. When asked about Russia, she admits she hates the Russian authorities, but cannot bring herself to hate the Russian people or the Russian language. “I became the person and history teacher I am by taking on the best, democratic part of Russian culture — Chekhov, Korolenko, Okudzhava,” Petrovska says. “I don’t want to give up their work and I’m not at war with the language and culture.”

Her century in Ukraine

Former schoolteacher Doba Huberhryts taught Russian language and literature. She was born 102 years ago in the southeastern town of Orikhiv, 80% of which has been destroyed in this war.

She remembers the Dnipro dam being built when she was a girl and how “everyone, young and old, carried at least one brick, participating in a common cause”. Molotov’s speech in June 1941 announcing the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union remains seared in her memory to this day. Her father and sister, a doctor, were immediately called up, but she and her mother were evacuated to Uzbekistan. She had completed two years of teacher training by then but found work there at a textile factory. “I had to feed the silkworms,” she says with a smile.

Centenarian Huberhryts with volunteers evacuating her from Kyiv. March 2022. Photo from personal archive

Huberhryts settled in Kyiv as soon as it was liberated at the end of 1943, she cleared rubble from Khreshchatyk, the city’s main avenue, and went on to work as a teacher for almost 50 years. Ever since Russia launched its full-scale invasion, she hasn’t gone down to the bomb shelter. She set up something like a cardboard shelter in her hallway instead, threw a mattress down and listened for air raid alerts on the radio.

“Don’t go near the windows and don’t turn on the light. I remember all that from the last war,”

she says. In mid-March, she was given two hours to pack up and move to Israel, which she did.

Being the oldest person to arrive in Israel from Ukraine, she immediately attracted media attention. She reads a lot, regularly calls former students in various cities around the world, and follows the news on two fronts. “A refugee from the south of Israel was brought to me on the day of the Hamas incursion and I was asked if I knew that Israel was also at war. I told them not to talk to me like an idiot,” she fumes. She says that despite her immense gratitude to Israel, she inevitably misses Ukraine, the country where she spent the first 100 years of her life.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]