Blood feuds may be an ancient rite with deep roots in Russia’s mountainous North Caucasus, but in Chechnya today they are prosecuted less in accordance with Adat, the Chechen system of customary laws and norms, and more in accordance with the code of the ruling Kadyrov family.

Indeed, Chechen head Ramzan Kadyrov never misses an opportunity to invoke the tradition, which perfectly encompasses the ideals of militancy, honour, and vengeance that underpin his regime’s brutal rule over the region. These days, however, blood feuds tend to end in “reconciliation” — code for financial reparations — between the transgressor and the victim’s family.

One such modern feud was resolved in January, when Chechen media boasted that the efforts of religious leaders and elders had reconciled two feuding families, the Turluevs and the Mamergovs.

The dispute began in 2006 when Dzhabrail Mamergov was convicted of murdering Apti Turluyev and stealing valuable items from his home. Mamergov was sentenced to a 25-year prison sentence, but following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, he was granted early release from prison to fight as a mercenary for the Wagner Group.

Mamergov was under no illusion that the Turluev family would be as forgiving as the state had been, however, and he sought ways to negotiate with them. The muftiate, the local spiritual board, asked him for 1 million rubles (€10,250) to carry out the reconciliation, which Mamergov paid.

While Mamergov did not respond to Novaya Europe’s questions about whether the reconciliation had really cost 1 million rubles, but Telegram channel NIYSO says that such “reconciliation procedures” are largely for show, but are encouraged by Kadyrov as a way to generate income.

Since 2010, the Chechen muftiate has overseen a committee charged with facilitating the reconciliation of blood feud enemies.

The committee serves a dual purpose, simultaneously burnishing Kadyrov’s image as a traditionalist while also lining the pockets of the muftiate.

The muftiate receives money not only from the transgressor — in theory, to pay for the reconciliation process — but also from Kadyrov’s administration itself, which showers the committee with extra benefits whenever it successfully brokers deals. In December, for example, its members received 26 new cars.

Even in this less bloody modern form, however, the tradition serves to reinforce the idea of collective responsibility, according to which a family must bear ultimate responsibility for the actions of its members.

The case of the Timurziev brothers

On 28 December 2020, a shootout on Vladimir Putin Avenue in Grozny killed 18-year-old Ingush twins Hasan and Huseyn Timurziev. According to official reports, the brothers had attacked police officers with knives, killing one and wounding another, after which they were shot and killed.

Ramzan Kadyrov at the scene of the Grozny shooting on 28 December 2020. Photo: Kadyrov_95 / Telegram

Later the same day, a message on the Chechen opposition Telegram channel 1ADAT warned the Timurzievs’ relatives that they could be held responsible for the dead brothers’ actions. Indeed, the twins’ closest relatives in Chechnya were duly detained the following day.

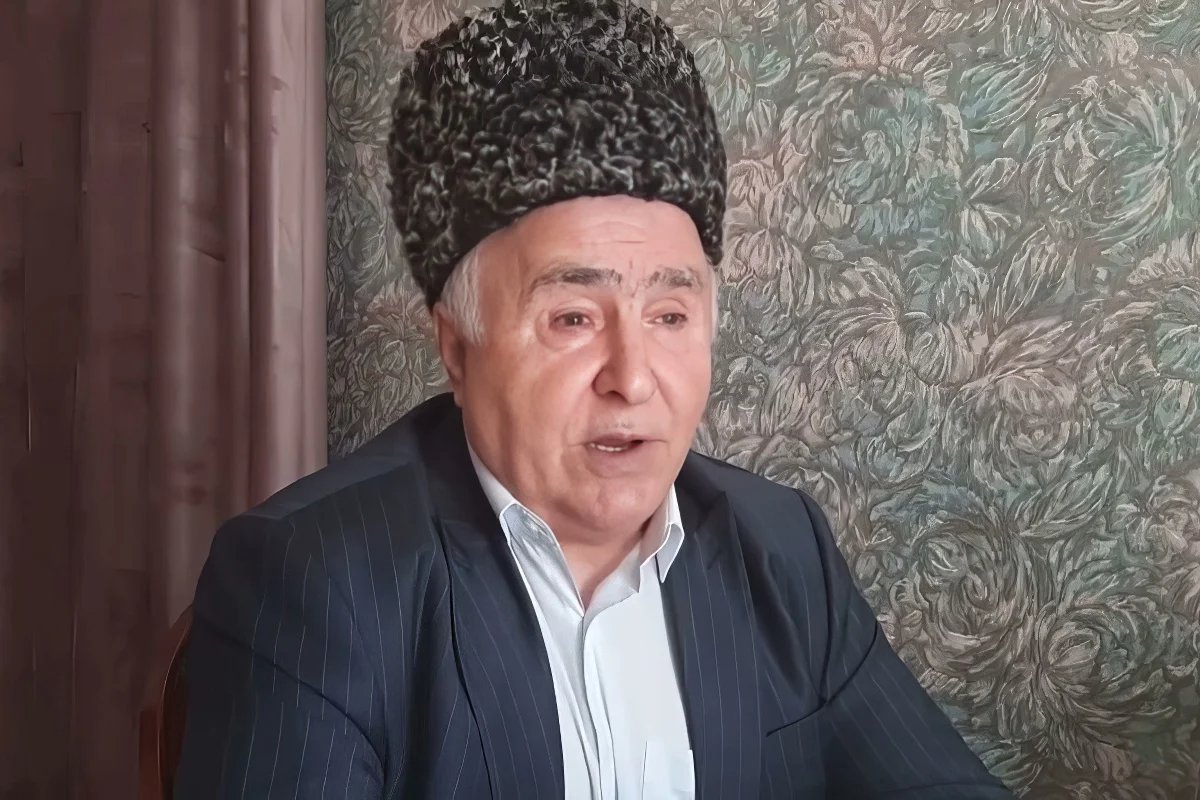

Then, on 30 December, the closely related Timurziev and Sultygov clans recorded a video message for Kadyrov in Ingush, a language mutually intelligible with Chechen, in which they demanded the Chechen head produce evidence that proved the guilt of the murdered twins. Sarazhdin Sultygov, a blind elder, spoke on behalf of the clans. He was blunt in his choice of words, demanding that Kadyrov return the Timurzievs’ bodies and publish footage of their killing online to see who had attacked whom first.

Sarazhdin Sultygov. Photo: Salavdi the Chechen / YouTube

Kadyrov couldn’t leave Sultygov’s challenge unanswered and promptly ordered Magomed Daudov, the chairman of the Chechen parliament, to declare a blood feud against the Timurzievs and Sultygovs on behalf of the family of the policeman supposedly killed by the brothers.

However, according to Adat, not being a relative of the dead policeman, Daudov had no right to declare a blood feud against the Timurzievs and Sultygovs. Daudov was also unable to do so in accordance with Sharia law, as in Islam, only the perpetrator can be answerable for an offence.

Magomed Daudov. Photo: Parliament of Chechnya / Miller KH / Wikimedia

“Islam rejects the practice of blood feuds, which date back to pagan times,” a theologian who asked not to be named told Novaya Europe. According to the Quran, he said, “the relatives of the person who committed the offence bear no responsibility for it. But in our region, Adat is often given priority over Sharia, and blood feuds are declared against the entire clan. This is absolutely forbidden in Islam.”

On the day the blood feud was announced, members of the Timurziev and Sultygov clans were summoned to the Ingush Interior Ministry where they were shown a video of the attack. Sultygov confirmed that the Timurziev brothers had indeed been the instigators, but still demanded that the Chechen authorities release their detained relatives and return the brothers’ bodies to their family.

But that was not the end of the story. Magomed Khanbiev, a current member of Chechen parliament and a member of Kadyrov’s own Benoy clan, spoke out about the incident, declaring a personal blood feud against Sultygov.

“I am addressing you on behalf of the entire Benoy clan. There are more than 10,000 of us, we have weapons, and we are in public office. You probably think your people will protect you, but you have no eyesight, and can’t even go to the toilet alone, and tomorrow, when I come for you and your entourage runs away, you won’t know which way to run,” Khanbiev said in January 2021.

The blood feud never came to pass, but a “reconciliation” did. On 7 January 2021, the Timurziev clan reconciled with the relatives of the murdered policeman in the Chechen parliament. The three detained members of the Timurziev family were released by Kadyrov on 12 January 2021, having supposedly been cleared of having links to terrorist organisations. The same day, patriarch Akhmetkhan Timurziev apologised to the relatives of the dead and wounded policemen on Chechnya’s state-controlled Grozny TV channel.

Six months later, he recorded a video message in which he asked Kadyrov to return the bodies of his sons for burial. The bodies were never returned, however, and a ritual funeral was ultimately held in the family’s ancestral village in Ingushetia with two tombstones marking empty graves.

Selective revenge

Kadyrov’s interpretation of Adat when it comes to blood feuds is very selective.

In December 2018, for example, Kadyrov’s cousin Turpal-Ali “Speedy” Ibragimov drove his Mercedes into a Lada with a couple and their two-year-old daughter inside, killing all three of them.

That evening, Ibragimov’s guards confiscated eyewitnesses’ phones so that footage of the accident couldn’t be posted online. The Chechen Interior Ministry announced that Ibragimov’s cousin, not Ibragimov himself, had been driving the Mercedes at the time of the crash.

Ramzan Kadyrov (left) with Turpal-Ali Ibragimov. Photo: Turpal-Ali Ibragimov / VK

In accordance with Adat, the victims’ relatives were entitled to take revenge on the man who caused the accident, but they chose not to.

A few days later, Adam Shakhidov, an adviser to Kadyrov, held a meeting with the wronged party. He went to the home of the dead man’s father with a TV crew and expressed his condolences, saying that “we must accept the decisions of Allah”. In the footage, the dead man’s father asks Kadyrov not to punish Turpal-Ali Ibragimov — suggesting that he was indeed the one driving the car.

Ibragimov, who headed one of Chechnya’s 15 administrative districts at the time and was widely said to be involved in extrajudicial executions carried out in the area, was not held accountable under either secular law or Adat for causing the accident, and today serves as the secretary of Chechnya’s Security Council.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]