Prison inmates granted pardons or early releases from jail to serve in Russia’s Storm Z penal military units are frequently discovering that the promises made to them when they enlisted weren’t worth the paper they were written on.

Sergey Cherepanov, 34, from the Novosibirsk region in western Siberia, signed a six-month contract with the Defence Ministry on 28 April. He had nine months of his six-year term still to serve when recruitment officers turned up at his prison. He refuses to say what he was in prison for, but will say that he “committed no crime” and “had been convicted without real evidence”.

Cherepanov was one of about 150 convicts recruited from his prison on that occasion, though many others had previously opted to fight as Wagner Group mercenaries, he says. When Wagner had come to the prison to recruit new fighters, Cherepanov had not been interested. “I was sure Wagner was lying about something. I trusted the state. But it turns out the state was lying.”

He agreed to enlist due to what he called his “strong love of Russia”. The money and a pardon, he says, only played a secondary role. In the combat zone, he was appointed commander of a company of assault troops, all of whom had been at the same prison.

He refused to discuss combat missions, but did say that “wherever Storm is fighting, life expectancy is in the hours”.

On 20 May, within a month of signing his contract, Cherepanov stepped on a mine near the town of Soledar in occupied eastern Ukraine. Half his foot was blown off and his leg was broken below the knee. As is the case for most former prisoners, the hospital refused to give him the certificate he needed for an insurance payout of 3 million rubles (€30,900). To date, he has only received the 500,000 rubles (€5,150) the government pays to wounded soldiers.

Cherepanov blames the non-payment on “corrupt Defence Ministry officials” who “want to rip people off and pocket the money”. He continues to have faith in Russian President Vladimir Putin, however.

“I admit there’s a lot he doesn’t know, and he only sees what is reported to him. We have only one of him, unfortunately. The country is huge, and he is on his own. And I don’t believe for a moment that he would approve if he knew what was really going on.”

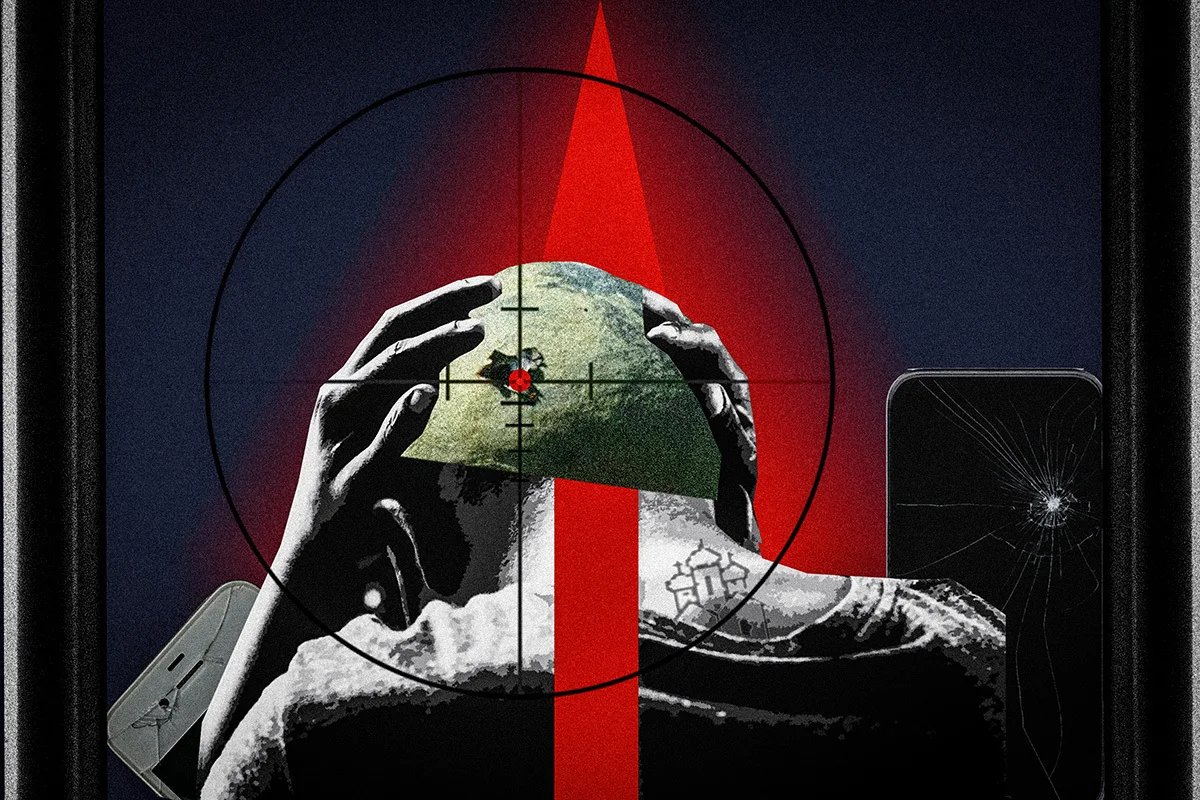

Illustration: Novaya Gazeta Europe

‘There’s nothing frightening about war’

Another former prisoner, Igor Kharaponov, from Kaluga in western Russia, signed a six-month contract with the Defence Ministry on 30 August, but within two months of fighting was caught in artillery fire and had to have his right leg amputated. In his case too, the hospital refused to issue the certificate required to be eligible for the insurance payout of 3 million rubles.

Kharaponov was released from a maximum security correctional facility with five years still to serve for murder. The Defence Ministry recruited 15 of the prison’s inmates to serve in its ranks.

His decision to go to war was based, he says, on his desire to “clean up his life and defend Russia”. Most former prisoners recruited into the military we spoke to used similar phrases.

Kharaponov says that “there’s nothing frightening about war”, and that, on the contrary, he enjoyed carrying out combat missions.

Military and prison life have discipline in common, but differ, according to Kharaponov, in that “there is no social rank at the front”.

“That doesn’t exist in the combat zone. We were told straight away to forget prison and codes of conduct. You can get killed for that sort of thing here. Everyone is equal in the war zone,” he says.

When asked about serial killers and cannibals being granted early release to fight in Ukraine, Kharaponov says such people should be executed or left to rot behind bars since “they would surely return to their old habits” if released. He has a different view of “ordinary killers”, however. “The only people who shouldn’t be granted early release are reoffenders.”

This was Kharaponov’s first time in prison. He is currently in hospital.

Illustration: Novaya Gazeta Europe

‘I’m missing two fingers’

Vlad Dyumin from Buryatia in Russia’s Far East signed a contract with the Defence Ministry on 14 October, but rather than being pardoned as Kharaponov and Cherepanov were, he was promised early release, a one-year contract that would automatically be extended until the end of the war in Ukraine, the salary and benefits of a professional soldier, and the status of a serviceman. Those who serve for six months and a pardon don’t receive such benefits.

Dyumin was serving a sentence for attempted murder. He says the case against him was fabricated, but he believes that a prior murder conviction had contributed to the court finding him guilty.

Before the prison recruitment campaign had even begun, he was sewing sacks, grenade pouches and other supplies for soldiers on the front.

About six months into his sentence, Wagner Group recruiters came to his prison but Dyumin was not considered due to the fact that he couldn’t do 40 push-ups. So he waited for the Defence Ministry recruiters instead. Like most former prisoners who enlist, he too went to war to “clean up the past”.

Like many others recruited from prisons, Dyumin was assigned to the assault forces as soon as he reached the combat zone. In one offensive, Dyumin’s detachment came under mortar fire and he lost two fingers on one hand.

He is sure that he will soon be sent back to the combat zone.

“There are people with only one leg or one eye in the forces and I’m only missing two fingers,” he explains.

Illustration: Novaya Gazeta Europe

‘Are we just meant to die on the battlefield?’

Denis (not his real name) from the city of Kursk in southwestern Russia signed a contract with the Defence Ministry on 13 May last year. Five months later, he stood on a mine that blew off one of his legs and sent shrapnel flying into his remaining limbs.

Denis received no compensation for his injuries.

“They promised me the mountains of gold and payouts that an ordinary professional soldier would receive, but in the end I got nothing. We were paid 100,000 rubles (€1,030) a month, rather than the 204,000 rubles (€2,100) we were promised, and some people didn’t get paid anything at all. I don’t understand, were we just supposed to die on the battlefield, and that be that?” the former prisoner asks.

Denis still had 11 years of a murder sentence left to serve.

“The prison sentence isn’t my reason for going to war. I have other reasons. I’m not the type of person who could watch civilians, including children and the elderly, suffer,” says Denis. “I could never understand the people who went to fight in order to be let out sooner.”

Denis went to war with 30 other former inmates from his prison. Before that, the Wagner Group had recruited around 100 prisoners from the same facility.

Despite his lack of experience, he was appointed commander of a platoon of 22 former prisoners upon arrival at the front. He prepared them for assault manoeuvres and took part in them himself. It was in one such assault that he stepped on the mine. He was dragged to safety from the battlefield by his comrades-in-arms and his leg was amputated the same day.

Denis refuses to say where this happened, fearing for his safety. Disclosing information about military operations could lead to him “being arrested and taken away and annulled”, he explains.

“And you know what ‘annulled’ means? It means getting shot and then being declared ‘missing in action’.”

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]