Russians waited for hours in the freezing temperatures across the country last week to add their signatures in support of Boris Nadezhdin’s candidacy in the 17 March presidential election. The only potential candidate standing on a platform of ending the war with Ukraine, for many in Russia Nadezhdin represents a last hope.

The Russian opposition is in tatters. Any politician daring to put themselves forward as a credible alternative to Vladimir Putin, is either dead, in prison, or in exile. There is also almost no independent press, and that which remains must contend with strict military censorship.

Given these conditions, the recent groundswell of popular support for a politician with a symbolic surname — nadezhda is Russian for hope — might not seem that surprising, even if Boris Nadezhdin’s supporters appear to openly accept that he has little chance of even making it onto the ballot, let alone winning the presidency itself.

While suspicions remain that Nadezhdin may be a spoiler candidate put up by the Kremlin to grant a thoroughly unfair election a degree of legitimacy, his campaign has become the sole possible form of legal protest for Russians opposed to Putin.

Party lines

Nadezhdin is the nominee of Civic Initiative, a small centre-right party founded in 2013, which does not currently have any seats in the State Duma, Russia’s lower house of parliament. Under Russian law, any would-be presidential candidate nominated by a registered political party that is not represented in the Duma requires 100,000 signatures of support to launch a nomination bid.

While that figure may be far less onerous than the 300,000 signatures of support required by independent candidates such as Putin himself, it remains a significant logistical challenge for a small party without a national volunteer network, not least as the rules stipulate that no more than 2,500 signatures can come from a single Russian region.

Despite that, Nadezhdin’s campaign announced on Monday that it had gathered over 200,000 signatures — twice the amount required — in anticipation of the Central Election Commission’s likely attempts to reject Nadezhdin’s candidacy application over a tiny infraction of the rules.

It’s safe to assume that many of the Russians supporting Nadezhdin today hadn’t even heard of him until recently. So why have more than 200,000 people already lent him their support? There are multiple reasons. First, it is the only legal way in the current situation to voice opposition to the war in Ukraine and persecution at home. Second, the campaign has provided people opposed to the regime with a rare opportunity to congregate with others like them, reminding them that people in the country wanting change are many in number.

Russians queuing up to put in their signatures for Boris Nadezhdin’s candidacy, St. Petersburg, 21 January 2024. Photo: Artem Priakhin / SOPA Images / Sipa USA / Vida Press

Nadezhdin openly says that Putin is “dragging Russia into the past” and that he “made a fatal mistake in invading Ukraine”. “We’ve been through turmoil and collapse twice in the past century. And now we are entering another rut of authoritarianism and militarisation. I won’t be able to forgive myself if I don’t try to stop it,” he said in his manifesto.

The campaign for Nadezhdin’s nomination — Russia is one of the few countries in the world in which getting onto the ballot is just as much of a challenge as winning the popular vote — received a huge boost in the second half of January, when several opinion leaders announced their support.

These included politicians, pop stars and supporters of the jailed opposition politician Alexey Navalny, including his wife Yulia. Russian opposition figures so rarely agree on anything, but they appear to have found common ground in supporting Nadezhdin as an opportunity to voice their anti-war position.

Nadezhdin is also supported by Yekaterina Duntsova, a journalist from the small town of Rzhev in the Tver region of western Russia, who also opposes the war in Ukraine and planned to run for president herself until the Central Election Commission rejected her application to register her electoral association.

Who is Boris Nadezhdin?

Born to a Russian family in Tashkent in 1963, Nadezhdin spent his earliest years in Soviet Central Asia before moving with his family to the town of Dolgoprudny in the Moscow region, a town to which his future political career would always remain closely tied.

After studying physics at university and working as a teacher, Nadezhdin went into politics during the glasnost era, and in 1990 was elected to the Dolgoprudny council. He is fond of reminding people that he has been contesting elections for almost 35 years, albeit with varying degrees of success.

His first attempt to enter the State Duma in 1995 failed, and from 1997 to 1999, he worked as an adviser to Boris Nemtsov, then Russia’s first deputy prime minister and later Russia’s de facto opposition leader who was assassinated in 2015. He was also an assistant to then-Prime Minister Sergey Kiriyenko, who is now a senior figure in the Presidential Administration.

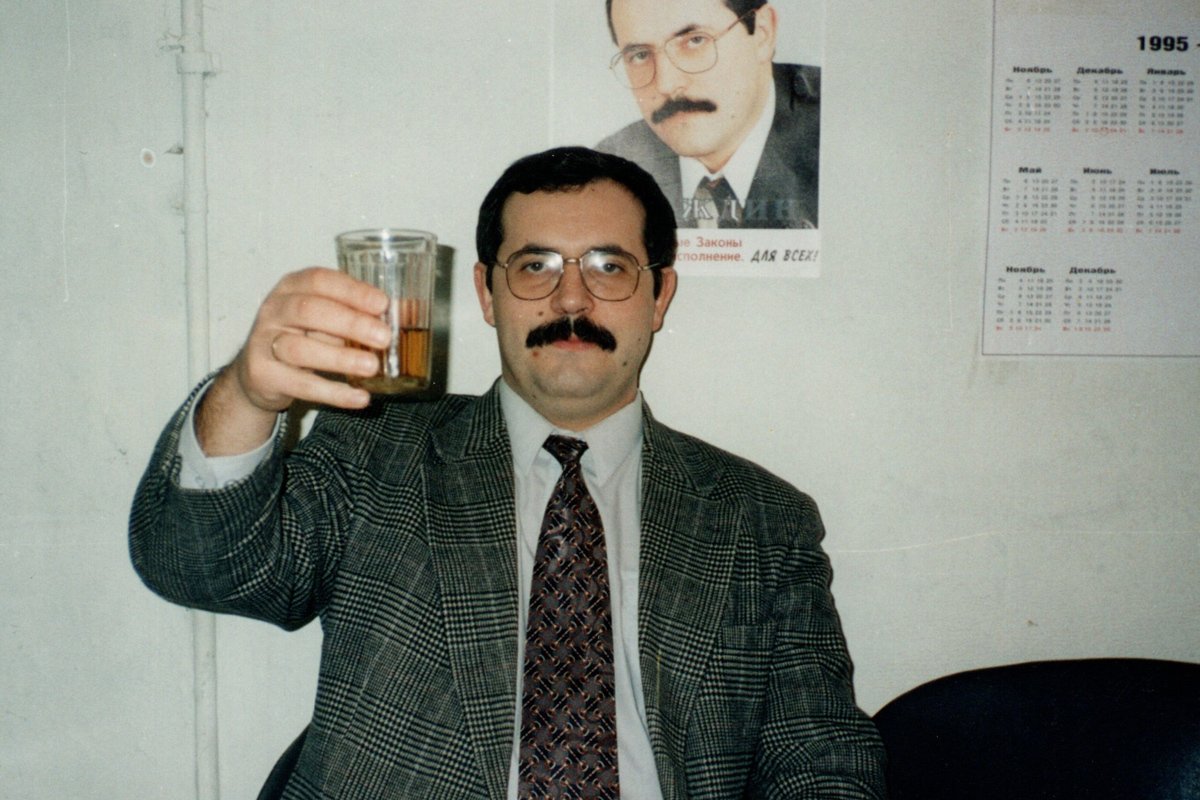

Nadezhdin in 1995. Photo: Boris Nadezhdin’s VK page

In 1999, Nadezhdin joined the Union of Right Forces, a liberal centre-right party founded by Kiriyenko, Nemtsov and future presidential candidate Irina Khakamada, and went on to win a seat in the Duma for the party, serving as a deputy from 1999 to 2003. After failing to secure his re-election, Nadezhdin became the deputy chairman of the parliamentary party until it disbanded in 2008. Since then, Nadezhdin has held no significant political posts, something that’s admittedly quite common among members of the opposition.

In 2016, Nadezhdin launched an unsuccessful bid to return to the Duma, running as a candidate for the Party of Growth. In 2018, he ran for governor of the Moscow region, representing the same party. A year later he tried his luck with A Just Russia — For Truth, a socially conservative, social-democratic party, and was elected to the Dolgoprudny town council. Last year Civic Initiative nominated him as their candidate in the Moscow region’s gubernatorial election, but the regional election commission rejected his attempt to register.

Last January, however, Nadezhdin promptly cut ties with A Just Russia after its leader in the Duma, Sergey Mironov, was photographed with a sledgehammer that had been given to him by the Wagner Group founder Yevgeny Prigozhin.

Head of A Just Russia Sergey Mironov photographed with Wagner chief Yevgeny Prigozhin’s sledgehammer. Photo: Mironov’s Telegram channel

Two months beforehand, footage of an apparent extrajudicial execution of a former Wagner mercenary who had deserted from his unit had emerged. “I definitely don’t want to stand alongside Prigozhin’s sledgehammer,” Nadezhdin later told a Siberian news website by way of explanation.

Nevertheless, Nadezhdin continues to head the Just Russia faction on the Dolgoprudny council.

“I have never been a member of the party, and yet I head the faction. How can I get out of it? It has six representatives on the council, and is the largest party in the region. … A Just Russia in Dolgoprudny is Nadezhdin, not Mironov,” he told Novaya Kazakhstan in October.

It’s hard to say whether Nadezhdin’s myriad links to different political parties is evidence of him lacking firm convictions or his pragmatism in the face of a political system in which there is no room for genuine opposition.

When asked by Novaya Kazakhstan about his frequent change in party allegiance, Nadezhdin responded by saying that he’d just “been around for a very long time, and Russian parties don’t last very long”.

In any case, such questions may be of little importance for now, as Nadezhdin finds himself, perhaps inadvertently, required to be the voice of liberal Russian society in the run-up to the election.

However, Nadezhdin appears to be under no illusions about his role.

“I don’t have the charisma of Boris Nemtsov or Alexey Navalny. I’m a nice, intelligent person, but I won’t be a Che Guevara figure,”

Nadezhdin told independent TV channel Dozhd last week, before ascribing his presidential run to circumstances simply falling into place.

The acceptable face of liberalism

While he may have lacked name recognition among Russian liberals until recently, Nadezhdin is no stranger to regular watchers of state TV, however, appearing as a regular guest on Russian talk shows since the early 2000s.

As a rule, these thinly disguised propaganda broadcasts have one commentator invited to represent the views of “liberals” in society, and whose answers are constantly interrupted by the heckling of the other commentators.

Nadezhdin appeared to accept his role as a “whipping boy” invited onto shows just to provide the other guests with a liberal to berate, but admitted that his invitations to appear on state TV channels dried up after the start of the war in Ukraine.

However, in his dwindling number of appearances since then, he has managed to make some brave statements. For example, when he appeared on pro-Kremlin channel NTV in May, he said that Russia needed a new president. “Under this regime, we have no way back to Europe. We need different leadership to build a normal relationship with European countries. Then everything will fall into place. Next year we have a presidential election. We need to elect someone other than Putin, and everything will be fine.”

In June, he even breached the taboo subject of the Russian troops killed in the war on state-owned propaganda channel Russia-1, saying that “the sooner this nightmare ends, the better for both Ukrainians and Russia”.

Photo: Boris Nadezhdin’s VK page

How liberal a liberal?

While campaigning in St. Petersburg earlier this month, Nadezhdin told local residents he met that he supported the repeal of what he called the “idiotic laws” on “LGBT propaganda” and spreading false information about the Russian military. When asked who his favourite politician was, he named Boris Nemtsov.

State-affiliated business daily Kommersant described the atmosphere at the meeting as resembling a protest, noting that the audience had criticised Putin’s policies and spoken in favour of ending the war in Ukraine.

Time and again, Nadezhdin returns to two main theses. First, that Russia should play a pivotal role in Europe, and not allow itself simply to become a Chinese vassal; Second, that Putin has completely destroyed all the state institutions necessary to Russia’s functioning as a normal, democratic country.

“For almost 25 years, Putin has slowly but surely been destroying the key institutions of the modern state — an independent parliament, an impartial judiciary, federalism, local self-government, freedom of speech, free and fair elections, and genuine competition in the economy and politics,” he says in his manifesto.

Whether or not Nadezhdin has much more to offer in terms of a vision for Russia’s future than these oft-repeated ideas remains to be seen. Many would also argue that for now, at least, it’s irrelevant, given that Nadezhdin’s sole task is to briefly represent the legal voice of dissent in the country for the next month and a half before it returns to business as usual.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]