Last month, the International Red Cross’s governing body in Geneva suspended the Belarus Red Cross from the international movement for its refusal to dismiss its secretary general Dmitry Shevtsov after he was found to have violated the organisation's fundamental principles.

Shevtsov’s breach of the Red Cross’s neutrality rules appears obvious and undeniable: he appeared in full military fatigues with the pro-Russian military symbol Z on them and confirmed on national television that the Belarus Red Cross was involved in transporting children from Russian-occupied areas of Ukraine to Belarus.

Still, suspension from the International Federation of the Red Cross (IFRC) remains rare, its communications manager Corrie Butler confirmed, saying that only three national branches have ever been suspended and that the IFRC considers it a “last resort”.

David Forsythe, a political scientist who researches the movement, told Novaya Europe that all other previous suspensions from the IFRC had been due to “administrative or financial problems” rather than the violation of Red Cross principles.

Dmitry Shevtsov, Secretary General of the Belarus Red Cross. Photo: sb.by

The Russian Red Cross (RRC) stands accused of misconduct strikingly similar to that of its erstwhile Belarusian counterpart. In February, the Ukrainian government placed the RRC on its sanctions list, where it will remain for at least the next 10 years, and the Ukrainian Red Cross (URC) has called on the IFRC to “take strict measures” against its Russian chapter for “violating the principle of neutrality”.

At the heart of both complaints is the RRC’s repeated co-operation with We Are Together, a Russian volunteer network that provides support to Russian military families and collects donations — including drones — for the Russian army. We Are Together displays the official RRC logo on its homepage, names the organisation as one of its primary supporters and frequently leads initiatives with the RRC to support Russian military families.

It is not unusual for Red Cross national societies to support military families in the countries in which they operate, according to Forsythe, and that activity is not typically viewed as a violation of the organisation’s neutrality. The American Red Cross, he pointed out, assisted the families of American soldiers during the Vietnam and Iraq Wars without reprimand.

Photo: Russian Red Cross

Butler agreed, calling it “common practice” for national Red Cross societies to provide “humanitarian support and mental health services” to military families. She said the IFRC had engaged in “detailed dialogue” with the RRC, who have assured the international body that they are not participating in “campaigns that support the military with military equipment”.

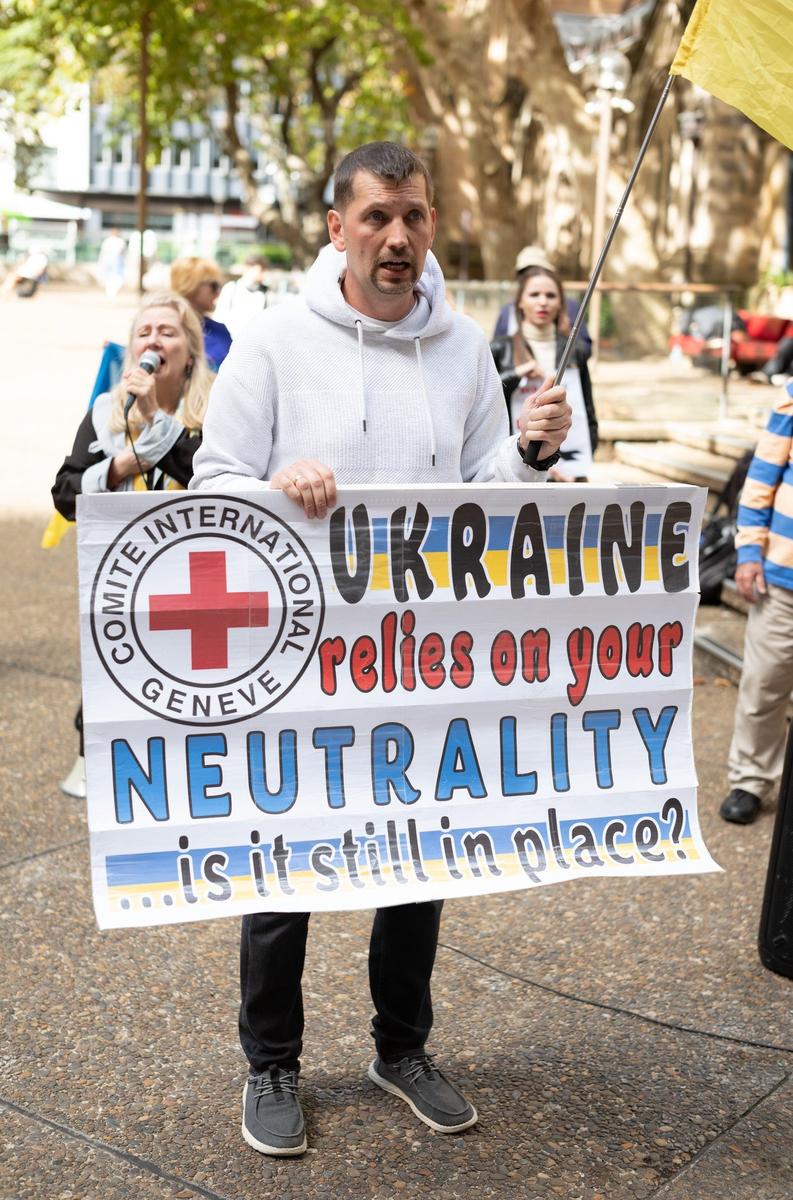

But activist Anton Bogdanovych, who sits on the Ukrainian Council of New South Wales, maintains that the RRC’s activities, in collaboration with groups such as We Are Together, goes beyond supporting military families; the organisation directly assists Russian troops. “Supporting families is one thing, while helping soldiers is another,” Bogdanovych said.

He and other activists have also decried the RRC’s connections to the People’s Front, another pro-war civil organisation. A political coalition whose nominal leader is Russian President Vladimir Putin, the group was founded to forge connections between ruling party United Russia and organisations such as youth groups and professional associations.

Australian Ukrainian activist Anton Bogdanovych at a rally protesting the actions of the Russian Red Cross. Photo: Nicholas Buenk

Heads of local RRC chapters, such as Anna Gromyko of Slavyansk-on-Kuban in southern Russia’s Krasnodar region, have been called out for reposting information about People’s Front initiatives, including a project called Everything for Victory, which delivers supplies to soldiers and civilians in Russian-occupied areas of Ukraine. The goal of the project, according to the People’s Front website, is to “prevent a humanitarian catastrophe”, but the equipment delivered by the group appears strikingly military and has included digital transmitters, camouflage nets, and quadcopters.

In several social media posts promoting the initiatives, Gromyko has included pictures of herself in an official Red Cross vest. In one photo she wears the vest while also holding a red banner emblazoned with a giant Z that reads: “For victory. The mission will be completed”.

Beyond constituting misuse of the Red Cross emblem — prohibited by the international Red Cross — these photos would also seem to violate the RRC’s own code, which states that its representatives must “refrain from publicly expressing their opinions about events with political overtones, and from engaging in political activities that could compromise the principles of impartiality, neutrality, and independence”.

Anna Gromyko of the Russian Red Cross poses with Russian soldiers. Photo: Anna Gromyko / Telegram

Gromyko is far from the only RRC affiliate to engage in activities with partisan overtones, however. Examples range from the RRC’s Voronezh branch reposting an advertisement for a first aid course held by a military training club and the Perm branch collecting donations of local honey for soldiers, to more obvious examples such as a mutual aid club at the Amur branch where the members sew balaclavas and tactical stretchers and weave camouflage nets.

Ukrainian news outlets have even reported that in the occupied regions of Ukraine, the RRC was distributing Z T-shirts and cups with Putin’s face on them.

Many recently founded RRC branches are even more fundamentally linked to the Russian military. The chapter in the city of Verkhnyaya Salda in the Ural mountains was established in summer 2022 by members of the local branch of the People’s Front, and the two groups promptly partnered with each other to hold a medical training course. In one photo from the course, RRC representatives can be seen standing next to a whiteboard that displays the phrase “All for Victory” and the People’s Front logo.

Despite these obvious political allegiances, the RRC still officially claims to be neutral. In December 2022, Bogdanovych called the Kamchatka branch of the RRC and offered them a donation of “drones and other military equipment” for Russian soldiers on the front line. On his personal Facebook page, he posted his recording of the RRC employee agreeing to accept the items.

Shortly afterwards, however, the RRC published a statement on its website saying that due to its status as a humanitarian organisation it had never accepted donations of military or “dual-use” equipment, and dismissed what it called the attempts to discredit the organisation as “slander and a provocation”.

Additional reporting for this story was carried out by Natalia Kapustina, Heino Ollin and John Martin.

Делайте «Новую» вместе с нами!

В России введена военная цензура. Независимая журналистика под запретом. В этих условиях делать расследования из России и о России становится не просто сложнее, но и опаснее. Но мы продолжаем работу, потому что знаем, что наши читатели остаются свободными людьми. «Новая газета Европа» отчитывается только перед вами и зависит только от вас. Помогите нам оставаться антидотом от диктатуры — поддержите нас деньгами.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]