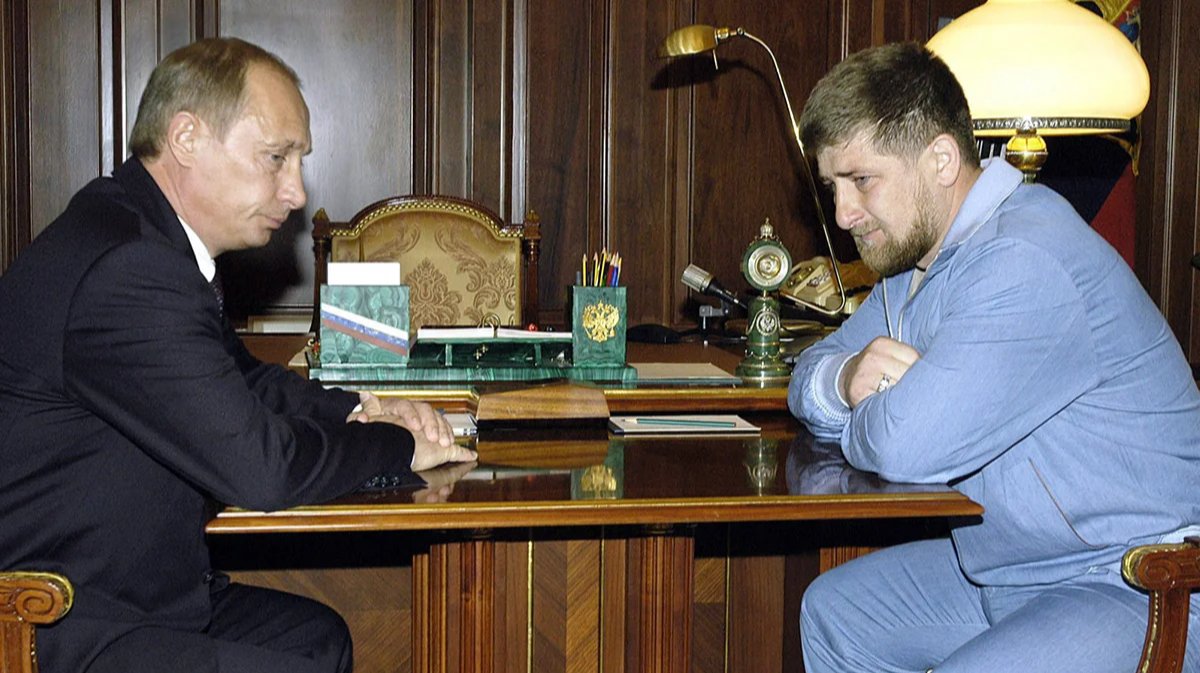

Twenty years ago, just hours after Islamist militants assassinated Chechen President Akhmad Kadyrov as he watched a Victory Day parade in Grozny, his nervous and deferential 27-year-old son Ramzan was ushered into the presence of Russian President Vladimir Putin in the Kremlin for an encounter that remains fascinating to watch two decades on.

Still widely unknown to the Russian public, Kadyrov is dressed incongruously in a blue tracksuit and speaks in faltering Russian without making eye contact. Until then, Kadyrov had been in charge of his father’s security detail, but on that day in the Kremlin an informal transfer of power took place in the full gaze of TV cameras as the younger Kadyrov was effectively tapped as Chechnya’s leader-in-waiting.

Kadyrov has now enjoyed almost totally unchecked power in Chechnya for 16 years. During that time he has been accused, alongside his guards and the Chechen security services, of systematic extrajudicial killings both in and outside of the republic, as well as torture, kidnap, and even the fabrication of terror attacks in order to justify the murder of civilians.

Now Kadyrov is attempting to legalise a practice he is widely believed to have employed for much of his reign anyway: the collective punishment of his enemies’ relatives.

“As has been forever customary, if someone is guilty and they cannot be found, you kill his brother, his father,” Kadyrov said at a Chechen government session in late December.

Collective punishment

“What Kadyrov says is true,” confirms Sergey Babinets, the head of human rights project Crew Against Torture, which has spend over a decade challenging police brutality and torture in Chechen courts.

Since the early days of Kadyrov’s rule, human rights activists have accused him of exacting revenge on both militants and his political rivals by punishing their relatives.

Smoke rises from the site of an alleged terror attack in the centre of Grozny, Chechnya, 4 December 2014. Photo: ERA / KAZBEK VAHKEV.

In December 2014, law enforcement agencies attempted to enter buildings being occupied by a militant group in Grozny, with the ensuing shootout claiming the lives of 14 police officers.

After meeting with ministers, industry leaders and security chiefs, Kadyrov took to social media to warn the population that: “If a militant murders a member of the police or anyone else, the militant’s family will immediately be expelled from Chechnya. They will be prohibited from returning and their house will be demolished.”

Masked individuals subsequently burned down houses belonging to the relatives of the militants involved in the 2014 attacks, forcing them to leave Chechnya.

This latest rhetoric about blood feuds is a clear signal to the Chechen security forces seeking to curry favour with Kadyrov and receive certain privileges, says Babinets.

Yet Kadyrov’s words don’t run both ways. Violence against human rights activists or journalists is not prosecuted with nearly the same degree of zeal. The most recent example of this disparity was the savage beating of Novaya Gazeta journalist Yelena Milashina and lawyer Alexander Nemov upon arrival in Chechnya last year. The pair's attackers remain at large, while Kadyrov typically stresses that he “cannot direct” the police or the Investigative Committee.

Yelena Milashina after her brutal attack in 2023. Photo: Abubakar Yangulbaev

“It is very convenient, because he cannot, by law, sanction violence. But in Chechnya there is only one law: 'Ramzan said'. The rest are excuses for people less familiar with the regional situation,” the Babinets says.

Fearing each knock at the door

Chechen human rights lawyer Abubakar Yangulbaev, one of Kadyrov’s most outspoken critics, is all too well aware of the targeted, extrajudicial violence and terror meted out by the Chechen regime.

In 2021, Chechen law enforcement agencies detained 37 members of the Crew Against Torture staffer's extended family. While most were later released, a month later armed men posing as police officers broke into Yangulbaev’s parents' apartment in the central Russian city of Nizhny Novgorod, forced his 54-year-old mother Zarema Musayeva into a car and drove her to Chechnya, supposedly for questioning in connection to a criminal case.

Zarema Musayeva in court. Photo: Crew Against Torture / Telegram

Later that day, Kadyrov recorded a video threatening the Yangulbaev family, accusing them of having links to terrorists and the political opposition, and vowing that the Chechen authorities would do everything they could to find members of the Yangulbaev family. “From now on, the family will have to be watchful, fearing each knock on the door,” Kadyrov said. Fearing for their lives, Yangulbaev’s father and his daughter left Russia shortly afterwards.

Following the Chechen leader’s threats, United Russia State Duma deputy and close Kadyrov confidant Adam Delimkhanov, recorded his own video, in which he vowed in Chechen to decapitate members of Yangulbaev’s family as well as anyone who dared translate the video into Russian.

Once in Grozny, Zarema Musayeva was accused of fraud and of using violence against a police officer and sentenced to five years in prison. A court subsequently denied her application for parole on the grounds that she had never confessed to her crime.

Death to all enemies

“It’s an old tale, of which history has many,” the late Novaya Gazeta columnist Anna Politkovskaya wrote of Kadyrov in the last year of her life. “The Kremlin raised a dragon and now it needs constant feeding, lest it breathe fire.”

Politkovskaya made her final public appearance on 5 October 2006 in a radio interview with Radio Liberty/Radio Free Europe in which she discussed footage of Kadyrov showing journalists the bodies of tortured and murdered civilians. “These people were abducted and killed for a reason that is completely incomprehensible — a PR stunt, done to be shown to journalists,” said Politkovskaya.

Two days later, Politkovskaya was murdered in the entry hall of her Moscow apartment building. Her assassins have never been brought to justice.

Anna Politkovskaya at work, 18 March 2004. Photo: Contributor / Epsilon / Getty Images

At least a dozen Kadyrov critics have been killed in the past two decades. As well as Anna Politkovskaya, those killed include two members of the Yamadaev family, a rival Chechen clan; Colonel Movladi Baisarov, an FSB lieutenant who was feuding with Kadyrov and who had been due to testify against him to a military prosecutor before he was shot in Moscow; Natalya Estemirova, a board member of Russian human rights organisation Memorial who was snatched off the street in Grozny in broad daylight and whose body was later found in neighbouring Ingushetia; Kadyrov's former bodyguard Umar Israilov, who accused his boss of torture and extrajudicial executions before he was shot in Vienna, and the opposition politician Boris Nemtsov, who was shot near the Kremlin in 2015.

Now aged 47, Kadyrov has traded in his tracksuit for the traditional garb and beard of a Chechen elder. He’s also much less guarded about his true intentions these days: at a meeting with ministers on New Year’s eve, Kadyrov openly vowed to kill all his critics, according to Telegram channel 1ADAT.

In the past, Kadyrov's instincts always led him to deny any involvement in his enemies' deaths, however unconvincing the performance he gave was. The fact that he's now openly vowed violent retribution against anyone who dares oppose his rule should be of concern to everyone.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]