The National Anxiety Index is a survey that has been conducted every three months since 2019 by the Russian Company for the Development of Public Relations (RCDSC), which works with major Russian corporations including Sberbank and Gazprom. The survey’s results always toe the official line.

Nevertheless, as we analysed the index results over the past year, we found that the most common concerns Russians had in the past year could all in one way or another be traced back to the war.

To measure anxiety, RCDSC’s researchers use a metric called the MediaYoung unit. The system is normally used to assess the effectiveness of an advertising or PR campaign, but the company has repurposed the tool to measure the spread of anxiety across social media.

That data is then analysed to determine the 10 most-discussed sources of anxiety in a given quarter, the belief being that people are far more likely to post about their fears on social media than to speak openly about them to researchers. In the company’s own words, the survey reveals people’s “grey-zone” fears, or those that lie beneath the surface.

How we spent this year

Summing up the year — where you travelled, what you achieved, what you’ll remember most — is a popular New Year’s social media ritual, which provides rich pickings for researchers attempting to paint a picture of the past year.

Most Russians, it seems, were disappointed with 2023. They began the year already tired of the war in Ukraine, and their posts from the first months of the year reflect widespread preoccupation with when the war would end, and, in particular, about the senseless bloodbath in the Ukrainian town of Bakhmut that was going on at the time.

Many people shared their fears about Russian casualties in Ukraine and expressed concerns about the various attempts to calculate the actual scale of Russian troop losses in the absence of an officially updated death toll.

In March, a fresh concern suddenly burst into people’s consciousness: sabotage.

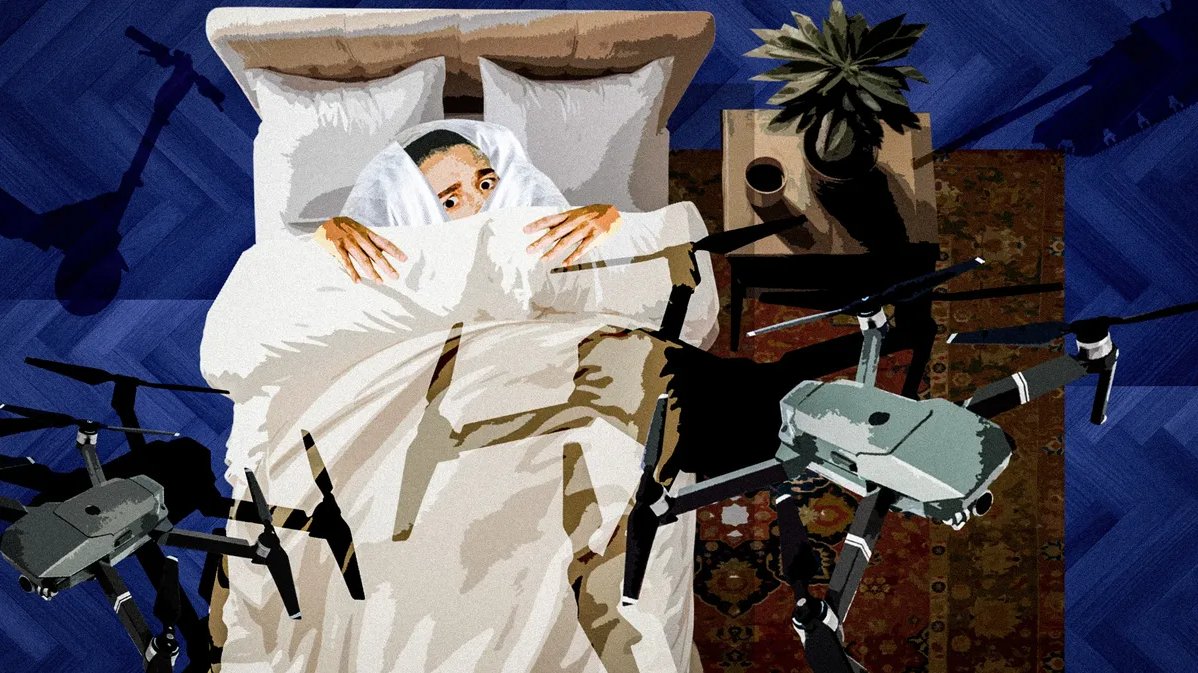

On 2 March, Ukrainian saboteurs — who turned out to be Russian far-right soldiers fighting for Ukraine — made the first of several incursions into Russia, entering villages in Russia’s Bryansk region where they encountered very little resistance from the authorities. The RCDSC said that fear of sabotage was then exacerbated by increasing drone attacks on targets in Russia and frequent government calls to prevent sabotage.

The other most common sources of anxiety included rumours about a new wave of mobilisation, rising food prices, the possibility of an AI-led attack on Russia, a string of gas explosions that had taken place across Russia, and the return of COVID-19.

Wagner Group fighters in Rostov-on-Don, 24 June 2023. Photo: EPA-EFE/STRINGER

From April to the end of June, the fear of sabotage became the dominant anxiety for most Russians. Fears about the consequences of the Wagner Group’s mutiny in late June was the second most frequently expressed anxiety in the period, with social media users expressing “fears that the situation could get out of control and end in armed conflict or civil war”, while the “unexpectedly rapid and peaceful resolution to the crisis caused confusion in a number of online media outlets, fuelling conspiracy theories and further anxiety”.

Other sources of anxiety in the second quarter of 2023 were the Ukrainian counter-offensive, fires and floods, the threat of nuclear disaster, and the dangers of bootleg alcohol, following a doctored cider that killed 32 people and left dozens of others needing medical attention in western Russia in June. The 10th-most common fear from this quarter was Russia’s continued exclusion from international sporting events.

The third quarter of 2023 was relatively calm for even the most anxious of people, with the number one fear being drone attacks, which had previously been included under the umbrella term of sabotage. The second-most prevalent fear was the further fall of the ruble, followed — at some distance — by rising petrol prices. The number 10 fear was the “impossibility of legally watching new Hollywood movies”.

Mobilisation in Russia, Rostov-on-Don. Photo: Arkady Budnitsky / Anadolu Agency / Getty Images

The fear of mobilisation also returned, brought about, according to the report, by recent amendments that raised the upper age limit for conscripts and increased the fine for failing to report to the military recruitment office when called up, as well as a new law that would strip dual citizens of their Russian passport for draft dodging.

However, if you look at the numbers, all of these fears — from the fall of the ruble to the impossibility of watching Barbie — are extremely minor.

In fact, based on the data, drone attacks trouble Russians almost three times as much as the fall of the ruble, and almost 12 times as much as the difficulty of travelling to Europe. And even the war seems to be less of a concern to people by autumn than it was at the beginning of the year: its day-to-day consequences apparently irking people more than the actual killing on the battlefield.

Novaya Gazeta Europe’s Anxiety Index

As the RCDSC has yet to release data for the fourth quarter of 2023, Novaya Gazeta Europe has attempted to fill in the blanks. To compile our list, we monitored news sites and social media networks for three months and selected the most “alarming” news stories. We measured interest in the stories through Google Trends and Wordstat, which allowed us to see what Russians were searching for on Google and Yandex. Here are the top five sources of anxiety we found:

1. Instability in the Middle East

The escalated conflict between Israel and Palestine has dominated the news since early October and heated debates on the events have similarly taken over social media. According to Google Trends, Russians Googled the words “Hamas”, “Israel”, and “Palestine” more on 7 October than at any other point in the last 20 years.

2. Waiting for demobilisation

Russian reservists mobilised in September 2022 are still serving in Ukraine a year and a half later, leaving many families bereft. On 7 November, the wives of mobilised soldiers in Moscow joined a Communist Party rally with signs saying “Bring the Conscripts Home”. The group’s Telegram channel, The Way Home, gained 24,000 followers in just a month. The keyword combinations “mobilised + home” are entered into the Yandex search engine about a million times per month.

3. Death of Putin

On 26 October, the General SVR Telegram channel published a message announcing that Russian President Vladimir Putin had died. Despite the channel’s dubious reputability, the news blew up on social media. Google Trends and Wordstat showed a record number of search queries on this topic: in October, the phrase “is Putin dead” was typed into Yandex almost half a million times.

4. Rising egg prices

Last year ended with a dramatic rise in the price of eggs in Russia — now 15% more expensive than they were just a month ago — and 36.5% more expensive than this time last year. Media outlets are full of egg-related headlines, including “what is happening to egg prices in Russia?” and “mass egg psychosis has begun”. In many Russian cities, a dozen eggs now cost 100-170 rubles (€1-€1.70). At some stores, customers stand in separate queues for eggs and are forbidden from buying more than a dozen at a time. One Russian grocery store has even resorted to selling eggs individually. The situation has given rise to countless memes, endless discussion on social media, and thousands of Google searches. According to Wordstat, in November the question “Why have eggs become more expensive” was entered on Yandex almost 32,000 times.

5. Pogroms in Dagestan

On 29 October, a mob riled up by anti-Semitic content on a local Telegram channel took control of the airport in Dagestan’s capital Makhachkala, having been told that refugees from Israel were arriving on a flight from Israel. The shocking images of the violent mob taking control of the airport and the total lack of resistance from the authorities caused widespread public alarm, despite the fact that state media largely avoided reporting on the incident. The day after the pogrom, the search query “what happened in Dagestan” surged in Russia.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]