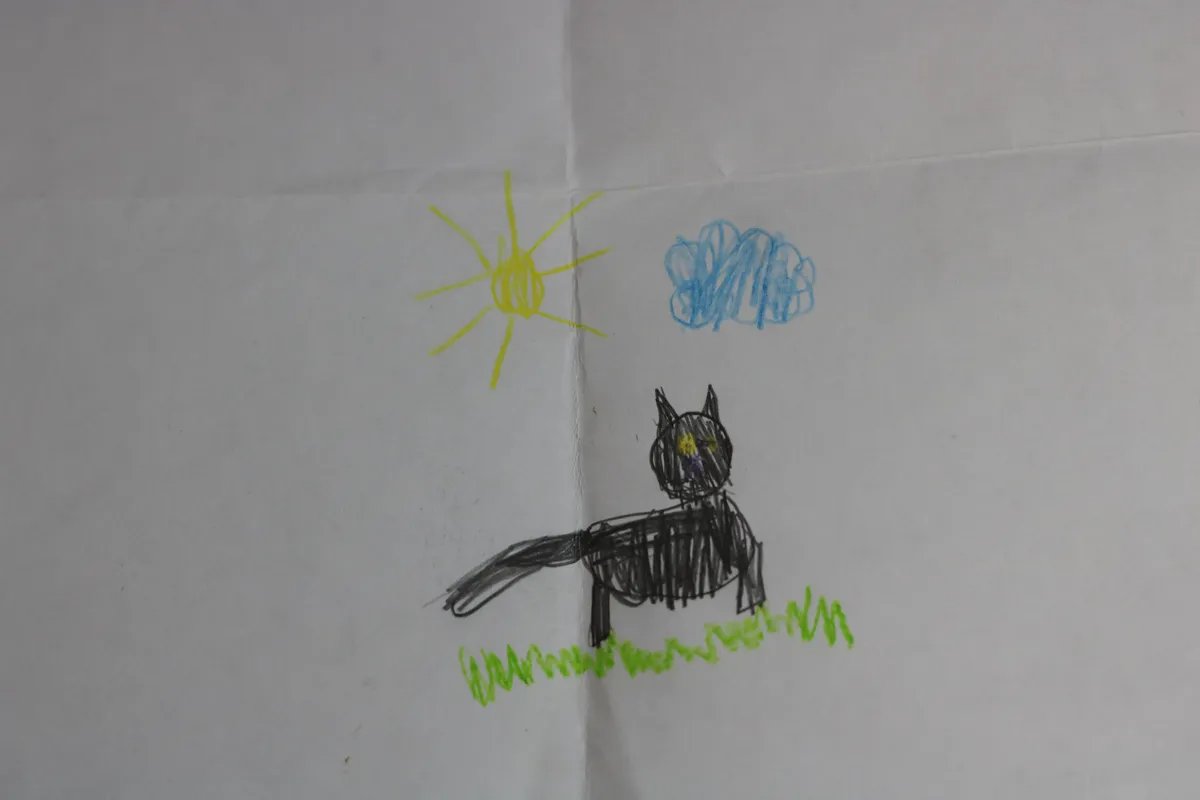

“I want to have this on me forever. It’s part of me, and I don’t know if I’ll ever forget it,” says Vyacheslav Korshunov, showing me a child’s drawing of a black cat, with the sun and a blue cloud in the sky above and green grass growing beneath its feet.

Korshunov was given the drawing by a girl who had been forced to leave Ukraine for Russia with her parents. The tattoo artist painstakingly transfers the simple motifs onto his skin while we talk.

The original drawing that inspired the tattoo. Photo: Pavel Kuznetsov

Hailing from Russia’s Bryansk region, which borders Ukraine, Korshunov began the dangerous job of assisting Ukrainian refugees when the war began. He continued doing so until it was clear he was about to be arrested, after which he moved to Georgia, where he now lives.

Among the few belongings Korshunov took with him were children’s drawings that had been gifted to him by those he helped. Today he’s having one of those pictures made into a tattoo in order to keep it forever. While the tattoo artist works, Korshunov tells me of his experiences.

Korshunov’s tattoo. Photo: Pavel Kuznetsov

‘I woke up and saw the news’

“Some of the refugees I met left me notes with kind words and sometimes they drew me pictures, especially the children. Now I have one of those drawings on my body forever, just as the people I met are with me forever.

I’m from Bryansk. I was born there and had lived there all my life. I went to school and to teacher training college there and worked wherever I had to. I was involved in activism. I went to rallies, worked on elections, collected signatures, like anyone else, and hadn’t noticed the time for quiet activism was over.

I woke up on the morning of 24 February 2022 and saw the news. I had a terrible feeling it was all over. I had lost Russia, my motherland, for ever and there was no future.

That day I went to the nearest stationery store, bought a black marker and paper and wrote: ‘No to war.’ I wrote the same thing on a mask. I called my friends and said that I was going to go to the square and might disappear for a few days.

The people on the bus looked like nothing was happening. They were living their normal lives. I got there, stood with my placard for about 40 minutes, and then a police car came for me. The cops came up and said: ‘Get in the car. We’re going to take your details.’ I knew all the anti-terrorism officers and investigators because I’d been apprehended before. But these were regular patrol guys, although I still recognised one of them. It was a guy who went to the same school as me, called K. He was only a few years older than me.

Korshunov holds a sign saying “No to war”, Bryansk, 24 February 2022. Photo from private archive

At the police station, I said to K.: ‘Mate, I know you! We went to the same school. Let’s have a chat.’ But he pretended he couldn’t hear me, and then that he didn’t know who I was. But we got talking. We were reminiscing when he said: ‘You sit around doing nothing and get money from the West. What for?’ I tried to explain that there was no money from the West, but he really thought that he was defending the motherland, and that we were idiots who’d been hoodwinked. I think he, and many other people, genuinely believe that.

I spent the night in a cell. K. gave me some cigarettes, and I was up in court in the morning. They let me read the police report. It said: ‘Behaved inappropriately when detained, was in a state of intoxication.’ It was signed K. I was given three days. I got off easily.

I didn’t hear the news for three days. I was hoping it would all be over. Three days later, I was released. I looked at the news and saw that none of it had stopped. I couldn’t sleep after that.”

Carrying bundles and sacks

“Refugees started coming to the Bryansk and Belgorod regions from Ukraine in large numbers in the spring and summer of last year. At first, in the spring, when the war had just begun, they were coming from big cities, but later on they were coming from the countryside too. They came however they could. Many didn’t even know where they were going to go next. Should they stay in Russia or travel to Europe? There were a lot of children and old people.

Chat threads for volunteers sprung up, and requests for help were published there. The coordinator would say things like: a family from the Donetsk region is on its way and needs somewhere to stay overnight in Bryansk. I would answer and start looking for somewhere through people I knew. Many people were sympathetic. Sometimes you had to meet people or bring them food, clothes or suitcases.

Suitcases were one of the biggest problems, because people didn’t have anything to carry their stuff in. Where were they going to get suitcases in the countryside? They were carrying bundles or sacks instead. One person had just wrapped their things in a jumper and left.

One time, I met a guy from Donetsk at the station in Bryansk. I found him, we went and got something to eat, laughed a lot, joked around. We got on well. He was open-minded, bright-eyed, very young. He had his whole life ahead of him. As we were walking along, he showed me his passport issued by the “Donetsk People’s Republic”. I’d never seen one before. It looked like it had been printed on an office printer. He wanted to give it to me as a memento.

He was glad just to be at a train station in Russia, happy to be safe, to stand around and chat. In the DPR, they could come up to him on the street and take him off to war on the spot. And in Russia, he was like, wow, you can walk around here! Then I took him to the bus station, he got on a bus and went to Moscow. He dreamt of becoming a model. I don’t think his dream will come true.”

Non-stop stress

“I was always aware the police could come for me at any time while I was trying to help refugees. I was searched twice even before the war, in 2019 and 2021, for my political activities. I was a volunteer in the local Navalny headquarters and my friends and I tried to raise awareness about corruption.

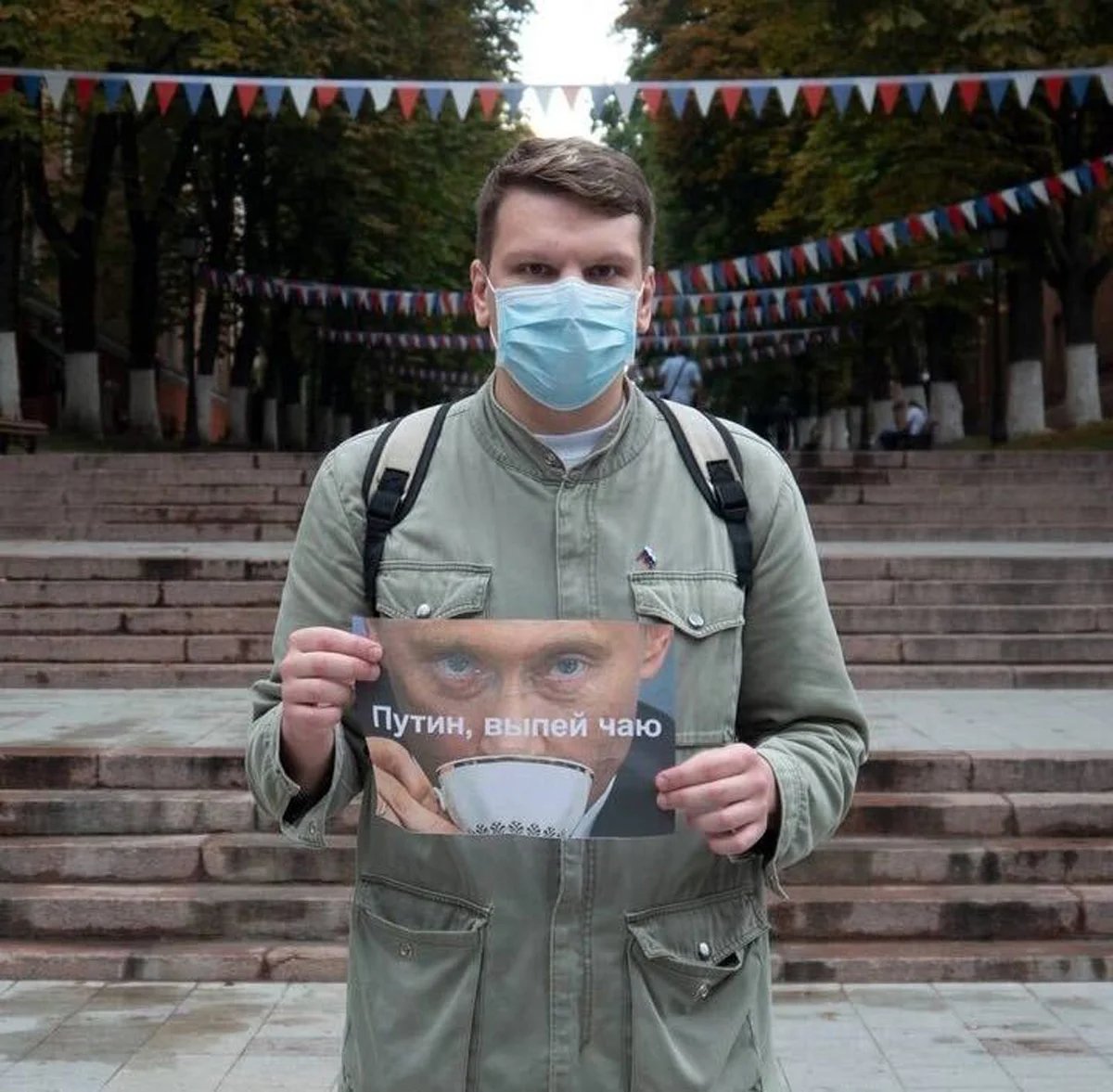

Korshunov holds a sign saying: “Putin, drink tea”. Photo: from private archive

From then on, I would notice any noise in the building, and I knew all the cars that were usually parked outside. When I went out, I would make a note of all the dangerous chats in Telegram so I could delete them if I was detained. It was basically non-stop stress. I was afraid to speak when in town. I was constantly looking over my shoulder.

But we — my friends and I, that is — still thought our region was OK, because we read news from other parts of the country, where things were totally bleak. People were being tortured and imprisoned. We were only threatened with having our genitals clamped in a vice.

When mobilisation was announced, a friend of mine was nabbed walking into his building. He was taken to the military enlistment office where they wanted him to sign up, but he refused. They wrote a report on him but let him go if he promised to come back the next day.

I knew I’d be next. So I either had to leave the country or go into hiding.

Friends suggested I go to Siberia. That same night I took a taxi to the bus station, bought a ticket and left.”

Guardian angel

“So I ended up quite far from the city, in a place where Ukrainian refugees were living. I stayed to help. They came and went. Some wanted to stay in Russia, others wanted to fly on somewhere via Istanbul. You can’t really go anywhere from this temporary accommodation. It’s basically a prison. Although most of them didn’t want to go anywhere else, of course. They hoped they would be going home soon. I worked and listened to their stories, which I can’t get out of my head now. There were entire families, with adults who could barely use the Internet, and all the responsibility ended up with the children, who were 15 or 16. They had to grow up early: if they couldn’t get their families out of hell, nobody could.

There was a constant flow, and everyone had their own story, their own terrible story. Those first few days I met refugees, I would just go and cry in the evenings. It’s impossible to ignore that your country is killing unarmed people in your name.

One story. A guy turned up with a dog, and the dog had a scar on its face. They’d got caught in an air strike. This man had lost his son and spent months looking for him in mass graves. His wife had a miscarriage due to stress. She went to Europe, and he continued looking for his son. A couple of months later, he gave up, took his dog and went to Russia. He realised that he would probably never find him.

I remember meeting a woman, Tamara Ivanovna, who was 83. She’d survived her house being hit. She’d been injured but had carried on living there, sleeping in her basement. She’d lost the hearing in one ear. She worried a lot and often cried. She was scared of people, but connected with me. Somehow, I was able to calm her down. We talked all the time while we were together. She would give me sweets she’d brought with her from Donetsk. I saw her off when she moved on and I was worried when we said goodbye. She was too, and I realised I couldn’t be with her all the way, I couldn’t offer any more support and probably would never see her again.

Korshunov with messages from grateful Ukrainian refugees. Photo: Pavel Kuznetsov

Some mornings, people would wake up and say their house or old school had been struck. There were lots of stories like that. I would try to joke around with people and cheer them up. It might sound silly, but I wanted them to feel kindness here so that they could at least relax for a day or two and feel safe. Otherwise you’d go mad. We usually stuck to neutral topics, didn’t mention politics and just chatted. They were really nice, kind people. They often tried to help me, although things were more difficult for them.

One day, a family of three arrived, a couple with a child, from the Kherson region. The child was maybe 12 or 14. He was so funny, playing online games all the time. The Internet connection kept cutting out and I would help him fix it. They’d had their own bakery before, making pizza and pies and that sort of thing. They said they had an Italian customer one day who said that he’d never had such delicious pizza in Italy. They were proud.

It turns out they had to stay in our shelter for almost two weeks. The husband had had a stroke shortly beforehand, and had an epileptic seizure on his way into Russia. They needed to stay where they were for him to recover. His wife cooked us potato pies and helped us however she could, and the husband would show me videos. There was one rock band he really loved and he showed me them performing. I asked a friend to print the group’s merch to give it to them when they were leaving.

We gave them a t-shirt.

They left, and that was the last we saw of each other. That’s not easy to get used to. You go and fetch these people yourself, you share food with them, eat breakfast and dinner with them. We collected money to buy them tickets. And we all cried when we said goodbye. I couldn’t give them my contact details because they had to cross the border.

But a few months later, they found me themselves and wrote to me. They said they’d gone to Poland first, and then on to Germany where they now live. ‘You’re our guardian angel,’ they wrote.”

‘The most important experience of my life’

“I used to go back to Bryansk a couple of times a month, but I spent the rest of the time at our shelter. I’d become estranged from the city. I came home, and the whole outside world seemed strange. People were living their normal lives, and I just sat there in silence. People were saying things, doing things, and I couldn’t utter a word. I felt nothing. I just wanted to go up to everyone and say, ‘There are people fucking dying every day, and you’re just sitting here drinking beer?’

Every time I went back, my mother told me the police had been to see the neighbours to ask about me. The neighbours confirmed that the cops were there all the time. They either stood near the entrance and questioned people leaving the building, asking them where I was and what I was doing, or they went door-to-door, though not to my mother.

But they did go and see her on one occasion. People in plain clothes came to the door early one morning at the end of March. They asked where I was and what I was up to. She didn’t answer and they began to threaten her. They said she needed to cooperate, that way it would be better for everyone.

Korshunov protests against police violence. Photo from private archive

They came back in the afternoon, this time in uniform. They told my mother that I had stolen or broken some woman’s phone and had to go to the police station to make a statement. That’s when I realised things were bad. I told other friends who were helping refugees, and they told me I had to go. I didn’t want to — I love Russia and want people to be able to live there in freedom. I had no idea how I was going to leave or what I was going to do. It was hard, but I knew it was time. Friends helped me with money for the ticket.

I threw away my phone, got to Minsk, and got on a plane to Tbilisi, which is where I am now.

Those six months I spent meeting refugees, living with them, sharing their joy and pain and listening to their stories, really changed me. I’m no longer ashamed of crying. People have had terrible things happen to them, at the whim of one crazy old man, and they have lost everything. Some have lived in their basements, others have lost loved ones, but they’ve all lost their homes.

I met over a thousand people during that period. Families with young children, old people, people with animals and children who had been forced to grow up fast. They were all wonderful, united by a single misfortune. I got to know some better than others, I became friends with some, I often re-read their thank-you notes. These are not just people fleeing misfortune. These are incredible, truly great people. I’m proud to know each and every one of them. This has definitely been the most important experience of my life. I will hold on to it, cherish it and never forget it.”

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]