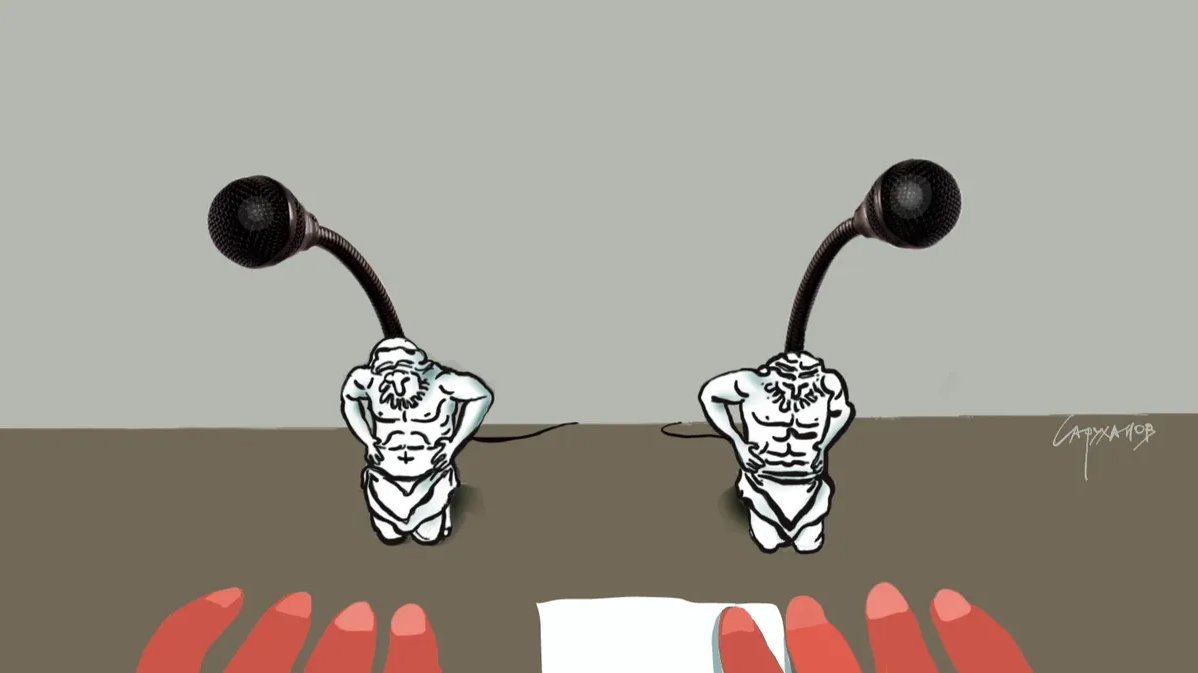

The annual Direct Line call-in TV show with Vladimir Putin had by 2021 become the only remaining bastion of public power in Russia. In a country without parliaments or courts, Russia’s president assumed the role of a miracle worker who solved problems live on TV, granting citizens’ requests for everything from new roofs to having gas installed in their homes — all the while reprimanding the governors who had failed to help them sooner.

The war in Ukraine led to a two year hiatus in presidential miracles, during which Putin began addressing Russians in a series of increasingly alarming speeches — each of which served to make people fear for their financial security and the wellbeing of their loved ones.

What would the all-powerful leader announce next: nuclear war, a new wave of mobilisation or the execution of his political opponents on live TV?

Two factors led to the resumption of Direct Line on Thursday. First, in a few months Putin will once again put himself at the mercy of the managed democratic process, and so for the benefit of that charade he feels a display of confidence and cosplaying concern for his subjects are in order. Second, Putin has found himself in an improved position in the last few months.

After two years of relentless bloodbath following the invasion of Ukraine, the situation no longer looks so dire. With the US elections on the horizon, Congress appears in no hurry to allocate further military aid to Ukraine; the Ukrainian counteroffensive has been unable to penetrate Russian defences; and Putin’s apologists in the EU, such as Viktor Orban, are now openly discussing the need to accept the Kremlin’s conditions for peace. All this means that Direct Line Putin is back — with big plans for us all. To raise the stakes further, journalists were invited to ask questions alongside ordinary citizens.

Putin begins his performance by saying the word “sovereignty” seven times: everything he’s done is for the sake of sovereignty, he claims, just as Walter White did everything for his family.

But there’s a shortage of sovereignty, just as there’s a shortage of eggs, so Putin has to continuously increase its supply.

True, sovereignty normally describes a people’s right to make its own political decisions, but when Putin repeats the word, he also adds to its meaning: now it also describes his personal right to take arbitrary decisions. You need more Putin to strengthen Putin, he reports at the end of the second year of his war.

He doesn’t shy away from the main question troubling Russians, according to the last Levada Centre survey, namely when will peace come? Peace will come, Putin declares, when we attain our objectives — which, by the way, remain unchanged. The objectives — also known as “demilitarisation” and “denazification” — are to destroy Ukraine as an independent state and ensure that the whole world recognises that destruction.

He appears to be setting out a plan for eternal war — one Russian citizens will be forced to accept when the president’s emergency powers are extended by popular demand on 17 March. Peace is not an option, and it’s no coincidence that the extension of Putin’s term was proposed by Artem Zhoga, a collaborator from the self-proclaimed “Donetsk People’s Republic”. Ukraine is an invented term, Putin maintains, but “Odessa is a Russian city”. More attacks and more deaths lie ahead. But a new mobilisation, he claims, will not be required — take his word for it. At least the awkward demands being made by the wives of the mobilised are now out of the equation.

But this show, dedicated to perpetual war as the new Russian norm, is held in a studio, where incoming questions texted by the citizenry flash up on blue screens. “Why does your reality diverge from ours?” says one. “We’ve given gas to China. When will Khakassia get it?” inquires another. “How do we get to the Russia shown on TV?” ask a third.

This whole set-up is prepared in advance and is intended for foreign audiences and to provide viral content on social media. You see, a strong leader doesn’t fear difficult questions, and even if he doesn’t answer them, he is perfectly willing to share the studio with them.

However, this arrangement only partially does its job. Questions may surround the dictator, showing up in the background before reappearing … but many thousands of people don’t get answers. They really do live in a different reality.

Instead, when asked about the shortage of eggs Russia is experiencing, Putin first opts for humour, an easy option given that eggs is also slang for balls in Russian, and then goes on to explain the egg deficit in terms that would make Marie Antoinette seem relatable: the people, quite simply, have eaten too many of them. Though he somewhat incautiously admits that he himself can sometimes polish off as many as a dozen in one sitting. They’re a valuable source of protein, after all.

His good mood loosening his tongue, Putin comments on the verdict against Alexandra Bayazitova, the administrator of a Telegram channel sentenced to five years in prison on extortion charges. He admits to not knowing about her case, and wonders aloud why resources were allocated to go after her? Is she some major opposition figure that needs to be pursued? It’s quite normal to go after major opposition figures after all, he says in a signal to his court.

Of course Putin understands the situation at the front better than anyone else. When a military correspondent questions the quality and quantity of drones being delivered to Russian troops, Putin interrupts the question and insists the correspondent admit that the situation is improving. Because it is improving, isn’t it?

To pay less for housing and utilities, Putin advises a journalist from Magadan to have children, because he is a “handsome young man”. In a tsarist flourish, he exempts pensioners from paying bank charges when settling those same bills (now that they can no longer take his advice to have more children). Civil aviation problems have occurred because Russia “bought too many foreign aircraft”, but “will produce 1,000 of its own by 2030”. Mercenaries will receive the same benefits as other combat veterans. The country’s “new territories”, i.e. the occupied regions of Ukraine, have already paid 170 billion rubles (€1.7 billion) into the Russian budget, which proves that the local economy is recovering, despite the more than 1 trillion rubles (€10.2 billion) that have been allocated to these regions from the federal budget. A so-called “soft” ban on abortion is akin to the anti-alcohol campaign of the Gorbachev era and will only benefit the country.

This year’s Direct Line, in which Putin reprised his beloved role as the sole guarantor of Russian sovereignty, wise man and bon vivant all at once, spells doom for a Russia that dreams of waking up to find that peace has returned and of living a normal life again. The course is now set for perpetual war and the total destruction of the state’s enemies. Even to reflect on the matter will henceforth be seen as harmful and considered a crime against the state.

Делайте «Новую» вместе с нами!

В России введена военная цензура. Независимая журналистика под запретом. В этих условиях делать расследования из России и о России становится не просто сложнее, но и опаснее. Но мы продолжаем работу, потому что знаем, что наши читатели остаются свободными людьми. «Новая газета Европа» отчитывается только перед вами и зависит только от вас. Помогите нам оставаться антидотом от диктатуры — поддержите нас деньгами.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]