Last week, Russia’s highest court deemed what it called the “international LGBT movement” to be an extremist organisation and banned its activities in the country. This is not the first time Russian courts have issued a blanket ban on a poorly defined group. In 2020, a prison subculture known as AUE was also declared extremist. The ad hoc “movement”, whose name translates to Prisoner and Criminal Unity, was, the court ruled, a danger to society that was in no way lessened by its lack of a manifesto, clear hierarchy, formal leaders, or even a single structure.

Banning what doesn’t exist

The Justice Ministry, which brought the LGBT case to the Supreme Court, argued that the movement’s activities amounted to “incitement to social and religious discord”. Human rights associations countered that no such movement formally exists.

Lawyers contacted by Novaya Europe suggested that the Supreme Court decision was directed against multiple LGBT organisations, initiatives and public activists, and identified LGBT organisations that have already been labelled “foreign agents” as those most at risk — the Justice Ministry’s “foreign agent” register currently includes 30 groups and individuals associated with the LGBT community.

For any of these organisations to be declared extremist, evidence that they form part of the “LGBT movement” is required. Yet lawyers fear that in the absence of such a movement, it will be much easier to allege involvement due to the vagueness of the definition.

‘All happy families are alike’. LGBT activists at a rally for International Day against Homophobia in St. Petersburg, 17 May 2014. Photo: Valya Egorshin / NurPhoto / Getty Images

This places managers, employees, participants and volunteers at LGBT initiatives at risk of prosecution. Once a court rules the activities of an organisation to be extremist, all of its structures must be shut down. Any subsequent activity will be considered a breach of criminal law, Alexander Verkhovsky, head of the SOVA Research Center, a Moscow-based non-profit, told the BBC Russian Service.

“Activists will inevitably be associated with some overseas organisation. This won’t necessarily mean membership somewhere, but just working contact, which LGBT groups in Russia have, of course,” Verkhovsky said.

Speeches given by Russian LGBT activists at international conferences or published resources could serve as grounds for criminal proceedings based on involvement with an extremist organisation, according to Verkhovsky.

Russian law makes involvement with an extremist organisation punishable by up to six years in prison, while founders of “banned” organisations can be jailed for up to 10 years.

Verkhovsky compared the current plight of the “LGBT movement” with that of the AUE in 2020, when the court’s decision was partially based on the fact that the AUE abbreviation was widely known, something that could potentially be used again in the case of the LGBT movement.

LGBT activists and feminists at a Labour Day rally in St. Petersburg, 1 May 2018. Photo: Anatoly Maltsev / EPA-EFE

The AUE precedent

Since Russia’s Supreme Court ruled the AUE was extremist three years ago, an extraordinary number of cases have been brought against its alleged members. The SOVA Research Center believes AUE ideology to be apolitical and to pose no threat to constitutional order, arguing that it shouldn’t therefore be subject to anti-extremist legislation.

Meanwhile, the number of AUE supporters increased sharply last year compared to 2021, according to state-owned news agency TASS, citing a source in law enforcement. This year has seen dozens of sentences being handed down for involvement with the AUE.

It is almost impossible to find any details on “extremist” cases, since rulings and sentences are only made public at the discretion of the court press service.

Rainbow ban

Now that the “LGBT movement” has been ruled extremist, future defendants will face administrative liability for displaying its symbols in addition to the criminal liability they already faced for involvement with an extremist organisation.

According to human rights activists, there will be far more administrative cases for displaying a rainbow or other symbols than criminal cases. That is the current pattern with other organisations which have been ruled extremist in Russia.

Experts are sure that the lack of official symbols of a non-existent organisation won’t prevent law enforcement initiating new proceedings.

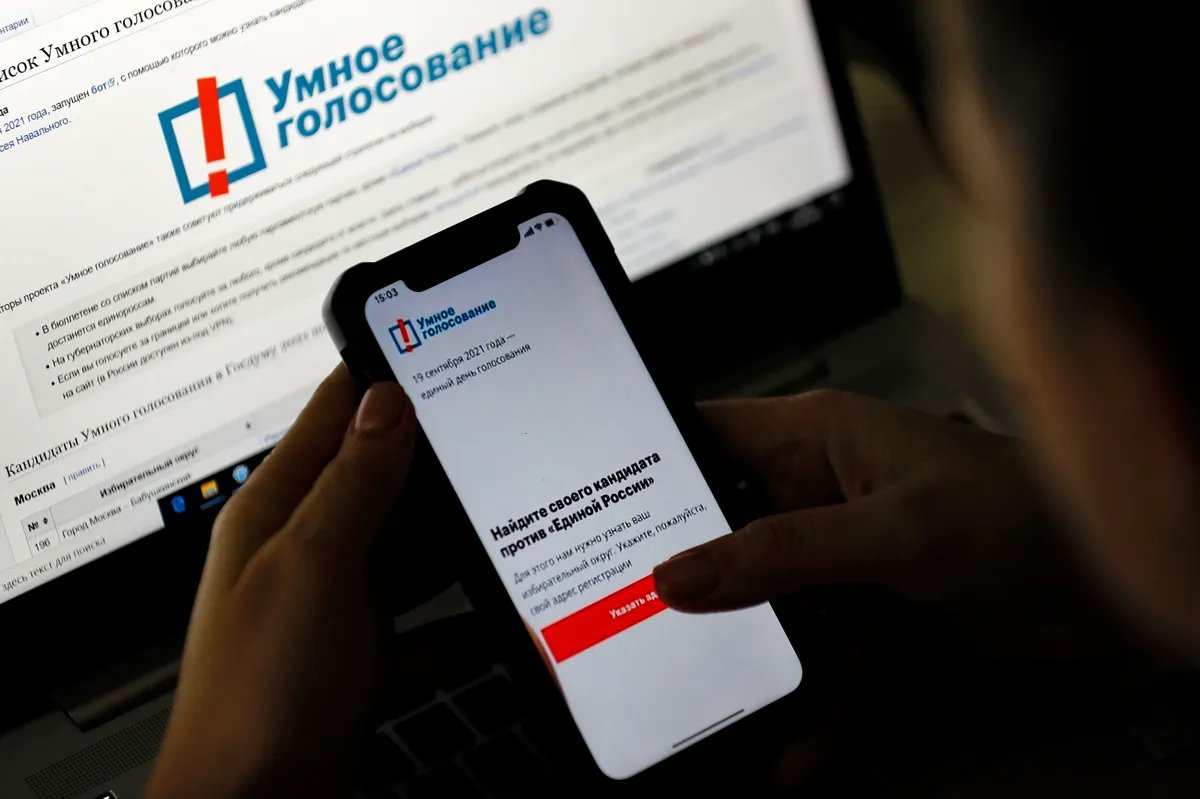

This is what happened to jailed opposition leader Alexey Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK), another organisation to have been ruled extremist. The authorities banned all the symbols used by the FBK and Smart Voting ― an associated app. Police have filed reports for the mere mention of Smart Voting on social media and for the use of the red exclamation mark associated with it, according to NGO Roskomsvoboda, which campaigns for internet freedom in Russia. Users have in some cases even been fined for old posts on social media made long before the FBK was ruled to be an extremist organisation.

Woman checking the Navalny Smart Voting app on her phone, Moscow, 17 September 2021. Photo: Sergey Ilnitsky / EPA-EFE

The authorities will from now on be in a position to declare people “supporters of the LGBT movement,” which could yet prove a very useful tool in disqualifying certain individuals from running in March’s elections.

Indeed, this is exactly what happened to Navalny supporters. In 2021, Ilya Yashin and Oleg Stepanov were not allowed to run in elections to the Moscow City Duma, the city’s parliament, and State Duma, the lower house of the national parliament, respectively. The electoral commissions and courts refused to register them as candidates precisely because of their support for an organisation ruled to be extremist. To justify their decision, they pointed out that Stepanov was the co-ordinator of Navalny’s Moscow headquarters, and Yashin was one of the organisers of a rally in 2019, at which there were calls for people to come out and protest.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]