Since the start of his second tenure as Hungarian prime minister in 2010, Viktor Orbán has crafted an image for himself as a beacon of conservatism, unafraid to champion “traditional Christian values” against a supposedly liberal global establishment, making him a politician fêted by far-right politicians around the world, from former US president Donald Trump to France’s Marine Le Pen.

Orbán’s disregard for democratic norms and civil rights, on the other hand, has earned him a very different kind of attention, with the EU deciding in July to withhold €12 billion in funds from Hungary over its breach of the bloc’s rule of law requirements. In 2023, US-based democracy think tank Freedom House condemned Budapest for “demonising the opposition and vulnerable groups”, while Amnesty International has described the situation in Hungary as an “ongoing rollback on human rights and violations of international and EU law”.

Yet none of this worries European officials quite as much as Orbán’s closeness to another “illiberal leader” — Russian president Vladimir Putin.

Hungary’s relations with Russia blossomed as Orbán moved to cement his power post-2010. Following Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014, Orbán described Russia as a “star” among countries that were “not Western, not liberal, not liberal democracies, maybe not even democracies, and yet making nations successful”.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 seemingly did nothing to dampen this admiration. While Orbán has publicly condemned the war, Budapest has provided Ukraine with little in the way of military assistance. Repeated calls for peace by the Hungarian government have understandably been interpreted in Kyiv as pressure for Ukraine to surrender its territories under Russian occupation. Though it has ultimately never vetoed the EU’s imposition of sanctions on Moscow, Hungary has repeatedly blocked EU initiatives to send aid to Kyiv.

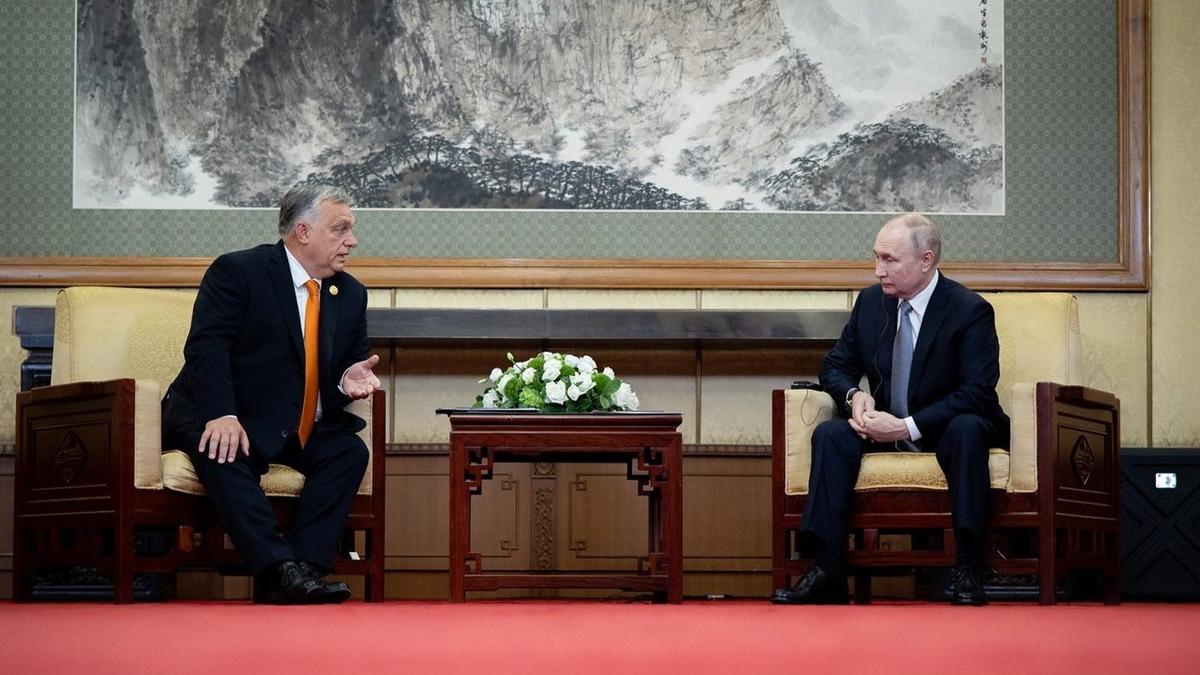

Vladimir Putin and Viktor Orbán shaking hands at the 'One Belt, One Road’ forum in Beijing on 17 October 2023. Photo: EPA-EFE/GRIGORY SYSOEV /SPUTNIK / KREMLIN POOL

Perhaps most shockingly of all, Orbán met Putin in Beijing in November on the sidelines of a conference marking 10 years of the Belt and Road initiative. The pair were pictured shaking hands in a cosy photo-op, and publicly reaffirmed their “commitment to bilateral tiesTo many, Orbán’s friendly encounter with a man wanted by the International Criminal Court for war crimes was an affront. Luxembourg’s Prime Minister Xavier Bettell described the meeting as “a middle finger to all soldiers, all Ukrainians that are dying every day and that have to suffer from Russian attacks”.

But for others, the event also exemplified a key aspect of Orbán’s approach to statecraft, in which ideology is primarily a political tool, but political pragmatism reigns supreme.

A political animal

At home in Hungary, Viktor Orbán is no longer an outlier or an upstart, but a pillar of the establishment, having played an active role in the country’s political scene for some three decades.

Born the eldest son to a rural middle-class family in 1963, Orbán studied law in Budapest and went on to work as a sociologist. He first came to prominence aged 26, when, as the spokesperson for the Federation of Young Democrats (better known today as Fidesz), he spoke at the funeral and re-interment of Imre Nagy, the executed leader of Hungary’s 1956 uprising against Soviet rule, in Budapest’s Heroes Square in June 1989.

Viktor Orbán’s speech at the funeral and re-interment of Imre Nagy. Photo: YouTube / Viktor Orbán

Orbán had co-founded the radically liberal Fidesz just a year earlier, the party base being made up of students and dissidents opposed to Hungary’s socialist government. As the communist regime began to crumble, Fidesz took an active role in the country’s democratic transition, and Orbán won a seat in the country’s first post-communist parliament, being elected Fidesz leader in 1993.

However, despite its initial success, Fidesz fared badly in the country’s next election in 1994, barely managing to scrape the 5% of the vote it needed to enter parliament. Orbán’s solution was to reorientate the party to the political right, a decision that sparked a rift within the party, with many members leaving never to return.

Today, it remains unclear whether Fidesz’s move to the political right mirrored Orbán’s true political beliefs or was electoral expediency. Similar questions about Orbán’s convictions have followed him throughout his career, not least regarding his position on Russia. How could someone who rose to political stardom by calling for Soviet troops to leave Hungary later become the Kremlin’s greatest supporter in the European Union?

Prime Minister candidate Viktor Orbán drinks champagne in the headquarters of the Fidesz-Hungarian Civic Union in Budapest, Hungary, 24 May 1998. Photo: EPA/ATTILA KISBENEDEK

Péter Krekó, head of the Political Capital Institute, a Budapest-based think tank, believes that Orbán’s policies do have some ideological basis, though he also characterises Orbán as a political animal who makes the necessary choices to stay in power.

“If you look back to his interviews even 20 or 30 years ago, you feel that he has this instinctive way of verbalising the nature of politics,” Krekó told Novaya Gazeta Europe.

However, he remained wary of Russia, describing its five-day war against neighbouring Georgia in 2008 as “imperial” and condemned the Kremlin for its invasion.

When Hungary’s economy floundered in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis and Budapest was forced to go cap-in-hand to both the IMF and EU for a bailout, Hungarian voters began to find Orbán’s conservative policies and his promise of new jobs, lower taxes, and less bureaucracy highly attractive amid ballooning unemployment.

That translated to a Fidesz landslide in Hungary’s 2010 parliamentary elections, giving the party a two-thirds supermajority: the first of its kind in Hungary’s post-communist history that gave it a free hand to that meant that Fidesz could force through any legislation it wished.

Putin’s playbook

Orbán used his supermajority to make sweeping changes to Hungary’s constitution, attracting widespread criticism. In a 2012 report, Human Rights Watch warned that the changes would “weaken legal checks on [the government’s] authority, interfere with media freedom, and otherwise undermine human rights protection in the country”.

Above all, Orbán had the country’s judiciary in his crosshairs, introducing legislation that ended the selection of judges for Hungary’s Constitutional Court by an all-party committee in favour of parliament, where Fidesz’s supermajority allowed it to handpick justices.

Orbán’s other focus was his control over the country’s media. “[He] learned a lesson in 2002,” says Krekó. “If you do not occupy the media when you come to power, you’re over,” adding that the government managed to bring the media to heel by ensuring Fidesz loyalists controlled all major outlets. Reporters Without Borders estimates that Fidesz took de facto control of 80% of the country’s media “through political and economic manoeuvres and the purchase of news organisations by friendly oligarchs”.

“Orbán has accumulated so many resources in the economy and media that he’s arrived at a point where he cannot make a mistake,” says Krekó. “It makes him almost a Teflon politician.”

“If the economy is in bad shape, then the media can blame it on Brussels. Nothing can burn you.”

These steps mirrored the methods used by Vladimir Putin in his own consolidation of power in Moscow a decade earlier: particularly the systematic takeover of all major TV channels in the early years of his presidency. Suddenly, Budapest had much more in common with Russia.

Initiating a foreign policy pivot towards Hungary’s so-called “eastern opening”, Orbán worked hard to attract investment from China, but also began courting Moscow, signing a deal with Russia’s nuclear energy agency Rosatom in 2014 to expand Hungary’s sole nuclear power plant. The project was never put out for tender.

Vladimir Putin and Viktor Orbán shake hands during their meeting in the Kremlin in Moscow, Russia, 31 January 2013. Photo: EPA/IVAN SEKRETAREV / POOL POOL PHOTO

Publicly, the driving force behind the eastern opening was purely pragmatic. Diversifying trade made logical, geopolitical sense, and markets in Russia, China, and beyond were strengthening quickly in the wake of the 2008 crash.

But the deals struck were not always the shrewd investments they appeared. For example, the Hungarian government borrowed €10 billion from Russia to cover the cost of the nuclear plant deal, ensuring Budapest would remain indebted to Moscow for several decades.

But not all of Hungary’s decisions on the world stage are made for solely rational or pragmatic reasons, experts say.

Orbán’s continued disregard for democratic norms had by 2016 become a consistent theme of the criticism he received from the rest of the EU member states, something neither Beijing nor Moscow were concerned about, of course. The fact that his cosy relationships with autocrats irked the EU so much ultimately became another reason to pursue them, as Orbán became more openly eurosceptic.

“Orbán didn’t start as an anti-Western politician. He became anti-Western as the antagonism between Hungary and the European Union and NATO became more bitter,” says Krekó. “He’s a revanchist politician: if you don’t treat him well in his eyes, then he will attack you.”

Hungarian journalist Edit Inotai added that Orbán’s ties to the Kremlin and Beijing also satisfied his own desire for recognition on the global stage. “It’s like when you have divorced parents. If one is criticising you, then you run to the one who will spoil you instead,” she says.

Crony-centric capitalism

While Orbán may have chafed at increasing Western scrutiny, his critics had good reason to be concerned.

Bálint Magyar, a former education minister, describes Hungary today as a post-communist mafia state, with Orbán at its heart. By putting loyal clients in charge of key assets, such as profitable businesses and media outlets, the prime minister has been able to consolidate his grip on power and make Hungary’s institutions work in his political and financial favour, Magyar says.

Many of these clients — some of whom have been friends with Orbán since his youth — have made substantial financial gains.

“In the case of Orbán, his network is a fraternity-based clan. Until 2015, Hungary’s biggest oligarch was Lajos Simicska, Orbán’s roommate who did military service with him,” says Magyar. “Then there’s Lőrinc Mészáros, he’s a former pipe-fitter, and not a genius I would say, but he was also friends with Orbán in elementary school. Now he’s Hungary’s richest man. This is an adopted political family with twin motives: the concentration of power and the accumulation of personal wealth, carried out bloodlessly by means of state coercion.”

Orbán himself has only ever declared modest personal wealth. But the fortunes of those close to him — many of whom head companies that have received government contracts worth significant sums of money — have led many to suggest that at least one of these old friends acts as Orbán’s “wallet”. Investigative journalists at direkt36.hu have uncovered cases of Orbán’s family receiving money through companies owned by Mészáros.

Viktor Orban at the Budapest Demographic Summit on 14 October 2023. Photo: Facebook / Viktor Orban

Orbán’s grip on power is all but guaranteed by this giant patronage network. Companies with Fidesz ties consistently get government contracts — especially those put out on “restricted” tenders, for which only certain companies are invited to bid on contracts valued at less than 300 million Hungarian forints (approximately €800,000).

A 2023 investigation by Hungarian news outlet Atlatszo found one Fidesz-linked company won 73% of the restricted tenders they were invited to, while others had a 100% success rate.

Such prospects provide a powerful incentive for those within Hungarian politics to remain loyal to Fidesz — and to Orbán.

“Even if you don’t agree with everything in Fidesz, if you don’t step out of line, you’ll be rewarded,” says Inotai. “So, many people in the party who may not agree with Orbán just don’t speak up.”

This system of cronyism is a replica of the well-established one in Russia, where many friends of Vladimir Putin have found themselves in positions of high power — such as Arkady Rotenberg, the president’s former judo partner, who is now a billionaire. Others are linked to shell companies and off-shore bank accounts that investigators have connected to Putin, such as cellist Sergey Roldugin — a long-time friend of the president’s who has been called “Putin’s wallet”.

Viktor Orbán at the Fidesz Congress 2023. Photo: Fidesz / Facebook

“A criminal organisation has two basic functions: it accumulates wealth for its members, and it gives them impunity. After 2010, Orbán faced an EU which provided Hungary with funds, but wanted oversight — undermining impunity,” says Magyar. “Eastern autocrats would not complain about the corruption risk and rule of law issues. They became an alternative source of wealth on Orbán’s radar, but this also created a dependence, especially in the case of Putin.”

Many of the construction deals related to the nuclear Paks II deal, for example, were not open to public tender; project documents will be confidential for the next 30 years. Such conditions invite corruption. Researcher András Deák estimates that such contracts account for approximately 40% of the project’s total budget, and that many of the companies involved will be linked to Fidesz.

This gives Orbán a reason to maintain strong ties with Russia — or even to echo the Kremlin line in return for staying in Moscow’s good graces.

An unfair fight

Today, Orbán’s grip on power remains unlikely to weaken. Hungary’s parliamentary elections in 2022 once more delivered landslide results for Fidesz, despite facing a strong challenge in the form of a largely united opposition.

Commentators raised concerns that Orbán exploited his power in Hungary’s public institutions to steamroller his opponents. In its report on the election, the OSCE highlighted biased news coverage that “limited voters’ opportunity to make an informed choice”, and pro-government social media advertising by Fidesz-linked organisations, which circumvented party spending limits. Meanwhile, the government rolled out a $5.35 billion social package in the run-up to the election, with incentives such as tax rebates and wage increases.

“Imagine we’re having a race,” says Magyar. “But before we start, I go and cut your leg off. Hey, you’re free to run, right? Except that you now have one leg. And that is what the elections in Hungary are like between the government and the opposition.”

In the meantime, Orbán’s pro-Russia rhetoric has continued. The government remains mindful of public opinion on issues such as Russia’s assault on Ukraine, Inotai says. But Fidesz knows it can rely on the full weight of the country’s state-controlled media to mould a domestic narrative, that can be justified by Orbán’s brand of conservative rhetoric. With this tool, the invasion of Ukraine and sanctions on Russia can be easily blamed for Hungary’s problems.

“Media campaigns can have a huge impact on public opinion,” says Krekó. “Yes, Hungarians are sceptical about the official line; there is little trust in the media. But when there’s this carpet bombing of information that comes from every source, it will have an impact on you.”

In the meantime, this media megaphone has other effects. Although Budapest claims that it seeks to build a stronger Hungarian nation, after 13 years of Orbán’s rule, Hungary is a divided country.

“I think there has been a lot of damage done in the last 10 years. I’m not saying that what we had previously was a paradise, but there was so much more room for discussion, for civilised debate,” says Inotai.

“Now, I avoid political topics with certain friends of mine who I know are Fidesz voters, because we can’t agree on facts any longer. When you criticise the government, there are people who make you feel like a traitor.”

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]