The United States has suspended social assistance for Ukrainian refugees who entered the country after 30 September this year. But even those who arrived before then face big challenges getting vital social security cover.

On 23 September, 45-year-old Zhumakhul Yusupova felt a pain in her abdomen. Usually Zhanna, as her family and friends call her, would solve the problem with some painkillers, but this time, they were no help.

Zhanna was afraid to go to the hospital due to the prohibitive costs of healthcare for the uninsured in the US, where her family arrived earlier this year as part of the Uniting for Ukraine (U4U) refugee programme.

Zhanna didn’t have medical coverage. Her application for Medicaid, which she submitted in July, was still under consideration by the Georgia Department of Public Health.

Zhana and Bayram Yusupov. Photo: family archive

At some point, the pain became unbearable, and Zhanna’s husband, Bayram, took her to the hospital, where she was diagnosed with gallstone disease. The doctors removed the stones from the bile duct and then cut out the entire gallbladder.

Zhanna spent a week in hospital. After the surgery, the excruciating pain went away. And then came the $67,000 bill, with an ominous note at the end: “This bill is not final”.

Twice a refugee

A week after being discharged from hospital, Zhanna greets me with a wide smile. She shows me pictures of her with the nurses who treated her, describing the excellent conditions in the hospital. “I’m very grateful to the doctors, though of course there are these bills… I’m afraid to open the letterbox. I don’t know how we will pay them.”

Zhanna Yusupova, is a Muslim and an ethnic Turk. Her ancestors came from the Georgian region of Meskheti. In 1944, the Soviet authorities deported them to Uzbekistan, which is where Zhanna and her parents were born.

The Fergana pogroms of 1989 put an end to the family’s quiet life. When Zhanna was 11 years old, street conflict broke out between Uzbeks and Meskhetian Turks. The clashes eventually led to a bloody massacre throughout the Fergana region. The Basatovs and their four children had to leave and look for a new home — this time in Ukraine.

“The Ukrainians received us very well, like we were family,” Zhanna says.

The Basatovs settled in the Donetsk region. There, Zhanna finished school, married Bayram Yusupov, and gave birth to three children: Amina, Bekir, and Abdulla. Over time, the Yusupovs built a large house in the village of Khrestyshche and built a farm, which brought them a good income. The Yusupovs claim that their family was one of the “richest in the village” — until Russia invaded Ukraine.

Guns in the field

In the spring of 2014, the Donbas saw multiple rallies against the new government that had been installed in Kyiv after the ouster of President Viktor Yanukovych. At these rallies, activists called for Ukraine’s eastern regions to follow the “Crimean scenario” and join Russia.

In April, separatists announced the creation of the Kharkiv, Donetsk and Luhansk “People’s Republics”. But while Kyiv managed to swiftly regain control over Kharkiv, full-fledged hostilities soon broke out in the so-called DPR and LPR — events that the Yusupovs were witnesses to.

“I remember one day we were driving along the highway from Sviatohirsk to our village. We were going past a field and saw that there were 11 artillery guns stationed there,” Zhanna recalls. “We had only just got back home when they started shooting. My daughter screamed so loudly. We thought we had lost her. It was terrifying. Thank God the house wasn’t hit. One shell landed in our garden.”

Zhanna with her daughter Amina. Photo: family archive

The Yusupovs were against the war from the start. Zhanna says their family wanted “Ukraine to remain united”. In 2016, the Yusupovs fled to Turkey, where they had relatives. Starting in 2021, the family would occasionally return to Ukraine — their last flight from Turkey was scheduled for 8 March 2022. Less than two weeks earlier, on 24 February, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and the Yusupovs never returned home.

Neighbours who remain in the village keep them posted about what is going on in Khrestyshche. They say that Ukrainian soldiers are currently living in the Yusupovs’ house. Zhanna shows me one of the latest videos sent by her neighbours. The windows of her house are broken, the fresh plaster has crumbled, and the floor is flooded with water. The grey slate roof is riddled with shell holes. Outside, on the concrete fence, hangs a brownish carpet, which used to be bright-red. Her neighbours explained the colour to her as the blood of a soldier who was killed inside the house by shrapnel.

The Great Lakes State

The Yusupovs got their chance to go to the US thanks to their 27-year-old daughter Amina, who personally witnessed the start of the war last February. After medical school, she married in 2018 and moved to Krasnohrad in Ukraine’s Kharkiv region, where she was living at the beginning of the invasion.

“In our neighbourhood, we only had helicopters flying overhead. Apart from that, there was no danger. We didn’t hear any bombings,” Amina tells me over the phone.

“There were terrible things happening in places that were less than an hour’s drive from us. A lot of people died.”

Last summer, Amina’s husband, Ruslan Sarvarov, went to Turkey to apply for the U4U program. Two months later, when the paperwork for the entire family was ready, the Sarvarovs flew to Okemos, Michigan, where their relatives had previously immigrated.

The Great Lakes State is not as popular with immigrants as New York or California. Amina says that the “job situation in Michigan is really bad”. She now has part-time jobs as a cook at two restaurants, earning between $570 and $1,200 a month in total.

Her husband tried to work as a trucker, but the money was only enough to pay the monthly car loan, car insurance, phones, rent, and taxes.

Celebrating Ukrainian National Day in Boston, Massachusetts, 24 August 2023. Photo: EPA-EFE / CJ GUNTHER

“We don’t seem to buy anything much, but we can’t save up any money at all,” Amina says. “Things haven’t worked out for us here. Our [Humanitarian] Parole is valid until September 2024. When it expires, we are thinking of going back to Ukraine.”

Benefits

Amina’s family, whose finances were and still are severely limited, has benefited from US welfare programs. Amina’s relatives began doing the paperwork for her family in advance, so they began receiving social assistance almost immediately upon arrival.

The Sarvarovs were approved for Medicaid, food stamps worth $1,000 monthly, and supplemental nutrition under the Women, Infants and Children programme. After a year, the family’s food stamps were discontinued.

Following Amina, the rest of the Yusupovs came to the States through the U4U programme in July 2023, but they did not go to Michigan. A family friend invited them to Georgia.

Bayram and his sons were hired to work at Five Brothers Auto in Roswell, a used car dealership run by Russian-speaking Meskhetian Turks. The work the Yusupovs do is difficult: repairing, painting and reassembling cars that have been in accidents. They have no previous experience in the business, so their wages are low.

Zhanna, who is still looking for a job, says that, like Amina’s family, they are “barely making ends meet”.

The Yusupovs applied for welfare as soon as they arrived in Georgia, but their Medicaid application was still being considered in late September, when Zhanna was admitted to the hospital with abdominal pain.

Georgia only provides Medicaid to children, pregnant women, people with disabilities, people over 65 and those living in a nursing home.

This year, there has been discussion of removing those restrictions. Georgia’s Republican governor, Brian Kemp, proposed giving coverage to low-income adults provided they work, study, or volunteer. Critics pointed out that many people cannot get a job precisely because of poor health, and improving it is too expensive without insurance.

A shutdown looms

Changing US policy on the war in Ukraine is now making it harder to get benefits. Military and humanitarian aid to Ukraine has been a central issue in this year’s budgetary discussions. For Democrats, continuing to support Kyiv is a key demand, while Republicans have been sharply opposed to it, wanting to focus instead on unresolved domestic issues.

US President Joe Biden signed a stopgap spending bill last month covering the next 45 days. It did not include aid to Ukraine. As a consequence, social assistance for Ukrainians who arrived in the US since 1 October was suspended.

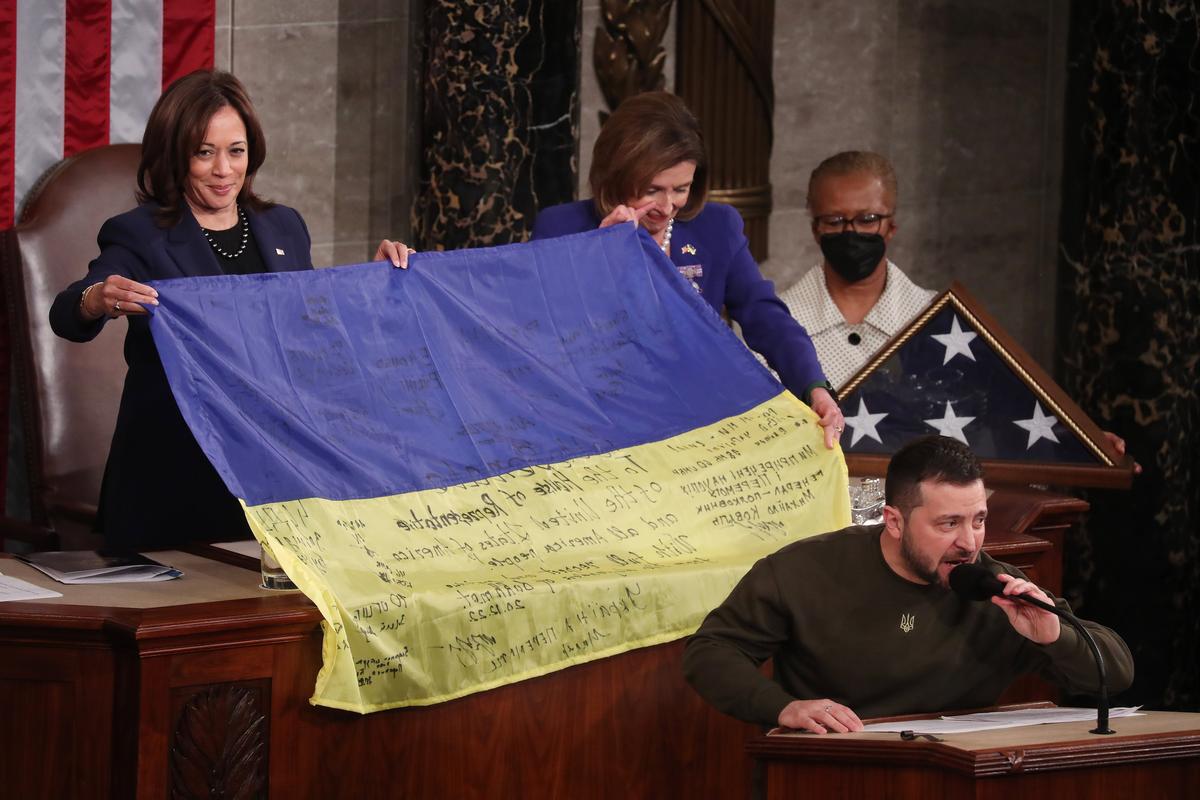

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky delivers an address to the US Congress in Washington DC in December. Photo: EPA-EFE/MICHAEL REYNOLDS

On 16 November, Biden signed another stopgap bill. By 19 January, lawmakers will have to make a final decision on spending for the military and housing, veterans affairs, transportation, and energy. All other budgetary issues have to be resolved by 2 February.

Novaya Europe interviewed Ukrainian refugees in red states who noted that, regardless of the budget vote, getting benefits will likely remain a hassle.

“When we came here, we didn’t think it would be so hard,” Zhanna Yusupova admits. “But I don’t regret being in the United States. If my husband or children were somewhere else, then I would regret it. But now they are all here. And my daughter is expecting a child.”

While this story was in the works, Novaya Europe received news that the Yusupovs’ Medicaid applications have been approved. But the issue with the $67,000 bill has not been resolved. Zhanna still has to find out whether she can use the insurance to pay for previous surgeries and, if so, whether Medicaid will cover the whole sum or only a part of it.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]