Robert Sapolsky, a professor of neuroendocrinology at Stanford University in California whose parents came to the United States as immigrants from the Soviet Union, spoke to Novaya Gazeta Europe about the neuroscience of psychopathy.

Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely, wrote the historian Lord Acton in 1887, gifting the world a memorable maxim that has never gone out of fashion, but is the theory behind the pithy phrase actually true?

Scientific research suggests the causality might be reversed: perhaps those who are biologically less empathetic are simply more likely to rise to power?

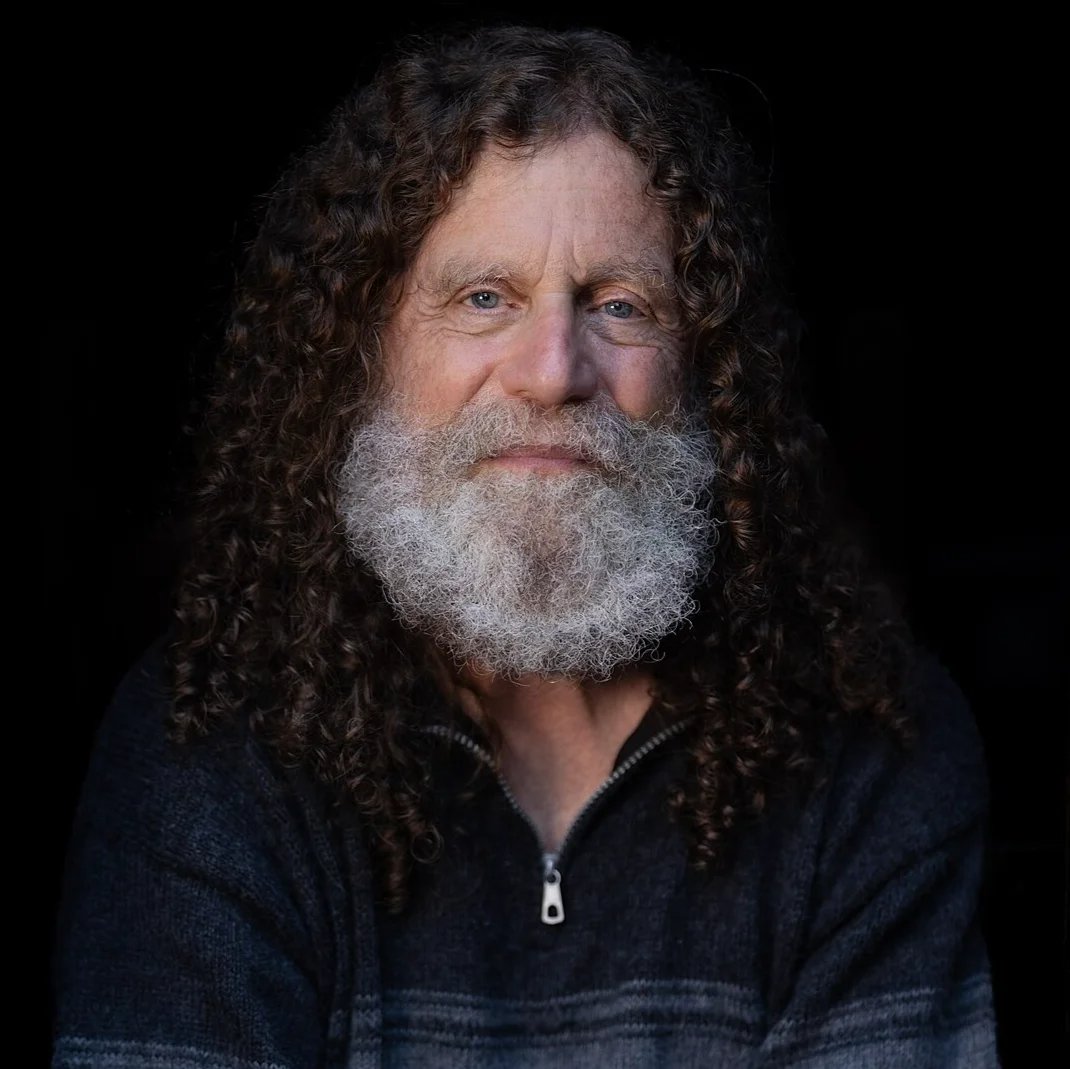

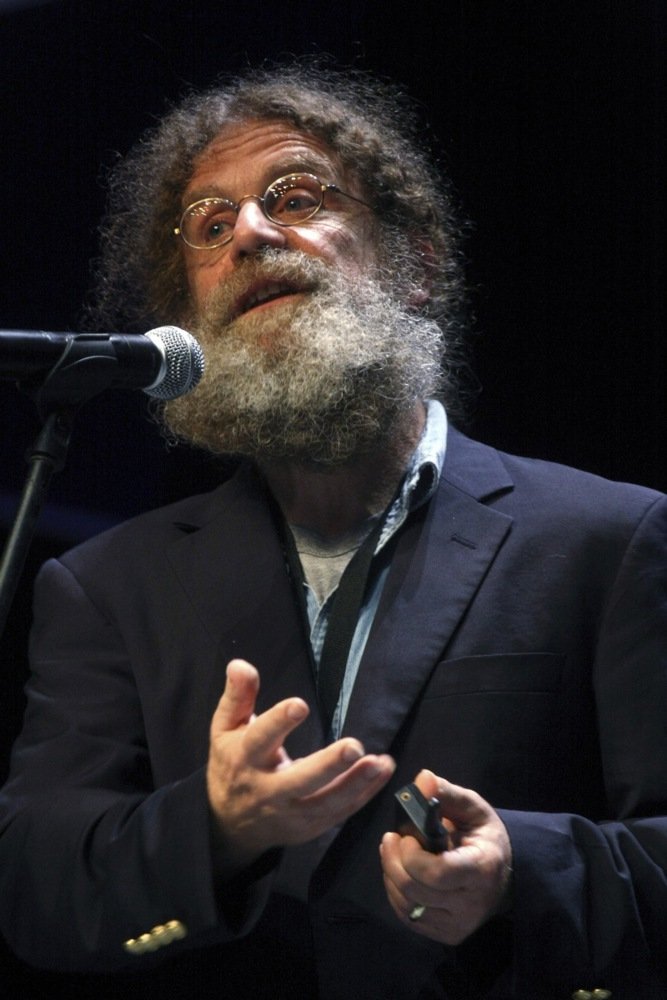

Robert Sapolsky

professor of neuroendocrinology, Stanford University

“There aren’t a lot of dictators whose brains we’ve been able to remove and study under a microscope,” Sapolsky jokes. Still, he says, he believes many dictators might be psychopaths, and explains this by describing the two main elements of psychopathy. First, psychopaths exhibit a total lack of empathy. Not only do they struggle to feel someone else’s pain, but they often have remarkably high pain thresholds themselves. Second, psychopaths have a very highly developed “theory of mind”, which is the term psychologists use to describe our ability to model and predict other people’s thoughts. For psychopaths, that “doesn’t lead to empathy or compassion. All it does is give them a great tool for manipulating other people.”

Sapolsky recalls a journalist who worked at the White House during the Trump administration telling him that Trump showed outstanding theory of mind. “He could walk into a room and chat with someone for 30 seconds and he would know their vulnerabilities. He knew how to exploit them.”

In some cases, psychopathy results from damage to the frontal lobe in what’s known as “acquired sociopathy”, Sapolsky explains. If the damage is suffered in adolescence or adulthood, people “can tell you the difference between right and wrong, but every single time [they are faced with a choice], they do the wrong thing.”

If the frontal lobe is damaged earlier in life, Sapolsky said, “it’s one step further. They will tell you these rules [about right and wrong] make no sense. [They will say], here’s why it is okay for me to kill someone. Take a 10-year-old kid who gets into a car accident and half his frontal cortex is destroyed, and that’s what you’re going to get.”

Sapolsky, who often provides medical testimony for criminal proceedings, recalled one trial in which the defendant had murdered nine people, but who had only started doing so after suffering a serious brain injury himself that left him in a coma for a month. “I was trying to explain to the jury that this guy does not have an evil soul. He’s a broken machine.”

Robert Sapolsky. Photo: EPA/Francisco Guasco

Sociopathy can also result from a combination of genes and childhood trauma, Sapolsky said, though he was careful to note that not all people who suffer childhood trauma become mass murderers. Lots of people just “wind up depressed or anxious or alcoholics”.

Returning to Trump, Sapolsky said he sees him, too, as a victim of childhood trauma. “Trump is a pathetic, broken person. His mother and father were both monsters. They drove his older brother to alcohol and death at 25. Trump has spent his entire life knowing the only people who have ever loved him were people he paid to love him. But don’t destroy our country. Just go be a sad alcoholic somewhere.”

Another American neuroscientist, James Fallon, has claimed that you can tell Putin, too, is a psychopath based on his biography and behaviour. Although Sapolsky hedges his answer on that one, he does admit that Fallon is “probably right.” If a person is willing to bomb a maternity hospital “you probably don’t need to sit with him once a week and have him talk about his childhood to [diagnose] something wrong there”, Sapolsky says.

Vladimir Putin at a Russian Security Council meeting, 30 October 2023. Photo: EPA-EFE/GAVRIIL GRIGOROV / KREMLIN POOL / POOL

And if science can help describe the psychopathy of dictators, it can also help describe the allure they hold for many people. Sapolsky mentioned one study which placed children in a room with new toys and had their mothers leave. “You look at five-year-olds and you can already see, is this a kid who gets excited by new things or is this a kid who becomes afraid of new things? You can see this biologically, with stress hormone secretion, with heart rate. And the amazing thing this study showed was that 25 years later, the kids who freaked out at novelty as five-year-olds are already likely to be voting conservative — voting for the likes of Trump.”

Donald Trump at a rally in Nevada, October 2022. Photo: EPA-EFE/PETER DASILVA

He also pointed to several experiments in the 1950s conducted by Jewish refugee psychologists who spent their postwar careers studying conformity and obedience. In one experiment, participants were shown three lines, one of which was clearly longer than the others. Ninety-nine percent of the participants correctly identified the longest line. Then they were shown the same lines in a different room, where people working for the psychologist told them another line was really the longest.

Sapolsky recalled that something like 70% of participants would ultimately change their minds and agree with people being paid to work on the experiment. This group, he said, can be further divided into “public conformists” and “personal conformists.” Public conformists pretend to agree with something in the moment. “Afterward, you say ‘What was that about?’ And they say, ‘Yeah, that was bullshit. But, you know, whatever. They seemed like nice people. I didn’t want to make a fuss.” Personal conformists, on the other hand, actually convince themselves. Asked after the experiment about why they changed their minds, “those people will say ‘I don’t know what was wrong with me [the first time], why the other line looked longer to me.”

“The second group is obviously far more scary,” Sapolsky said. Here, too, he explained, neurological differences play a role. For people in the second group, “when everybody else around them is saying ‘no, no, actually that one is longer,’ a part of the brain called the amygdala, which is about fear and anxiety, activates.” These people, he added, are more likely to have a history of childhood abuse.

In such circumstances two other parts of the brain are also activated: first the insula, which is related to feelings of disgust and repulsion, and then the hippocampus, which is responsible for memory. “What’s your brain doing? It’s telling your hippocampus to remember something different than what it actually does. And then what’s really amazing is that you [also] see activation of the visual cortex, which is at the back of the brain.” Overwhelmed by fear and disgust, the brain is overriding and amending what the eyes originally saw.

To draw political parallels, Sapolsky suggested that at a certain level of atrocity, public conformists will eventually change their minds about dictators. “Public conformists say, ‘you know, Russia needs a strong leader — my god, Yeltsin was drunk all the time — and we need something that will make us an economic power again. And yeah, he’s a jerk and he’s heartless, but you know, sometimes you need somebody like that.’ These are the people who are eventually going to say, you know, “This is not right.” Maybe they’re going to say that within two minutes of Ukraine being invaded, or maybe it’ll take, you know, a year and a half.”

However, personal conformists will never have that moment, Sapolsky says. “The people whose [levels of] fear and anxiety and disgust are through the roof — they’re the ones who, five years later and 50 years later, are still going to be saying, ‘They were trying to destroy us. They really were a menace.’”

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]