Russia’s National Guard — the federal agency often referred to as Putin’s private army — is in the process of becoming Russia’s second military force. Reforms introduced last month now make it possible to call up regular citizens to serve in its ranks, and permit its recruits to use “arms and military hardware”.

What are the origins of Putin’s “Praetorian Guard” and how has it steadily gained so much power over the years?

The plan to create a national guard in Russia subordinate directly to the president was hatched in 2012 with its main task described as “ensuring national security and defending constitutional order”.

This decision didn’t come out of nowhere: in 2011, as Vladimir Putin and Dmitry Medvedev prepared to swap back their roles as Russia’s prime minister and president, protests erupted all over Russia after parliamentary elections saw seats only won by four Putin-affiliated parties. Unnerved by the scale of the popular anger, the Kremlin judged the country’s “constitutional order” to be weaker than ever.

Putin and Medvedev at the 2011 United Russia congress at which Medvedev announced he supported Putin’s return to the presidency and confirmed he would gladly serve as prime minister. Photo: EPA / SERGEI CHIRIKOV

On 2 April 2012, Russian newspaper Nezavisimaya Gazeta first reported on the Kremlin’s plans to establish a National Guard, but the claims were quickly dismissed by Putin’s spokesperson. According to the newspaper, the organisation would be headed by the chief of Russian Internal Troops, a paramilitary force of the Russian Interior Ministry. Back then, that position was occupied by Army General Nikolay Rogozhkin.

In 2013, Putin appointed his old friend and longtime bodyguard Viktor Zolotov to be Rogozhkin’s deputy. The following year, Rogozhkin would be promoted to being Putin’s envoy to the Siberian Federal District, clearing the way for Zolotov to take his place.

Director of the National Guard of Russia Viktor Zolotov. Photo: Kremlin.ru

Zolotov, a contemporary of Putin who has known the president since the 1990s when he was the bodyguard to Putin’s mentor and St. Petersburg mayor Anatoly Sobchak. In 2000, Zolotov became Putin’s head of security, and has long been one of the people Putin trusted the most, according to political scientist Nikolay Petrov. This can be used to explain Zolotov’s constant career advancement, becoming Russia’s deputy interior minister following the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014 and being promoted to the rank of general in 2015.

Vladimir Putin on a visit to North Africa in 2006. Behind him on the left is Viktor Zolotov, then his head of security. Photo: Konstantin ZAVRAZHIN / Gamma-Rapho / Getty Images

In April 2016, Putin signed a decree on the establishment of Russia’s Federal Service of National Guard Troops, with Zolotov at the helm. The Internal Troops were no longer controlled by the Interior Ministry following the creation of the National Guard.

The strategic decision to create a second army out of the Internal Troops was born out of the 2011-2012 protests, according to Petrov. “Likely, that was when Putin grew afraid and realised that there are worse threats at home,” says Petrov, adding that Putin must have been disappointed in Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB) which had not prevented the protests from happening.

The establishment of the National Guard changed the overall balance between security forces and law enforcement agencies in the country. “There was now a new organisation that Putin could trust — and it was essentially led by his bodyguard,” notes Petrov.

Without a team

As per Putin’s decree, the Internal Troops weren’t the only forces that became part of the National Guard. All security police units, including rapid response teams and police aviation, were now under its control. The National Guard ended up acquiring its own fleet, too.

The only force that the Interior Ministry managed to keep to itself by some miracle was the Grom special squad, which had 65 servicemen in 2017. Any police operation that had a need for more forces now had to rely on the National Guard troops.

Riot police officers during a protest in Moscow organised by Alexey Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Fund in 2017. Photoо: EPA / YURI KOCHETKOV

The change significantly decreased the capability of the police to respond to calls quickly, says a former Interior Ministry investigator who agreed to speak with us on condition of anonymity. According to him, if an act of vandalism, robbery, a brawl between fans, and rape are happening at the same time in some area, then there’s no one to answer all of these calls. “This is how things currently stand in most big cities,” he says.

Another problem, according to him, is that the Interior Ministry no longer has its special units. Interior Minister Vladimir Kolokoltsev tried to rectify the situation by expanding the Grom special squad, the only unit he had left at his disposal. “Kolokoltsev relied on Grom to be able to carry out operations without depending on the National Guard,” says Nikolay Petrov.

Kolokoltsev’s actions led to ire from Putin himself. “We do not need a second National Guard. What we need is the good coordination that we always had,” Putin said during an expanded meeting of the Interior Ministry Board in 2017.

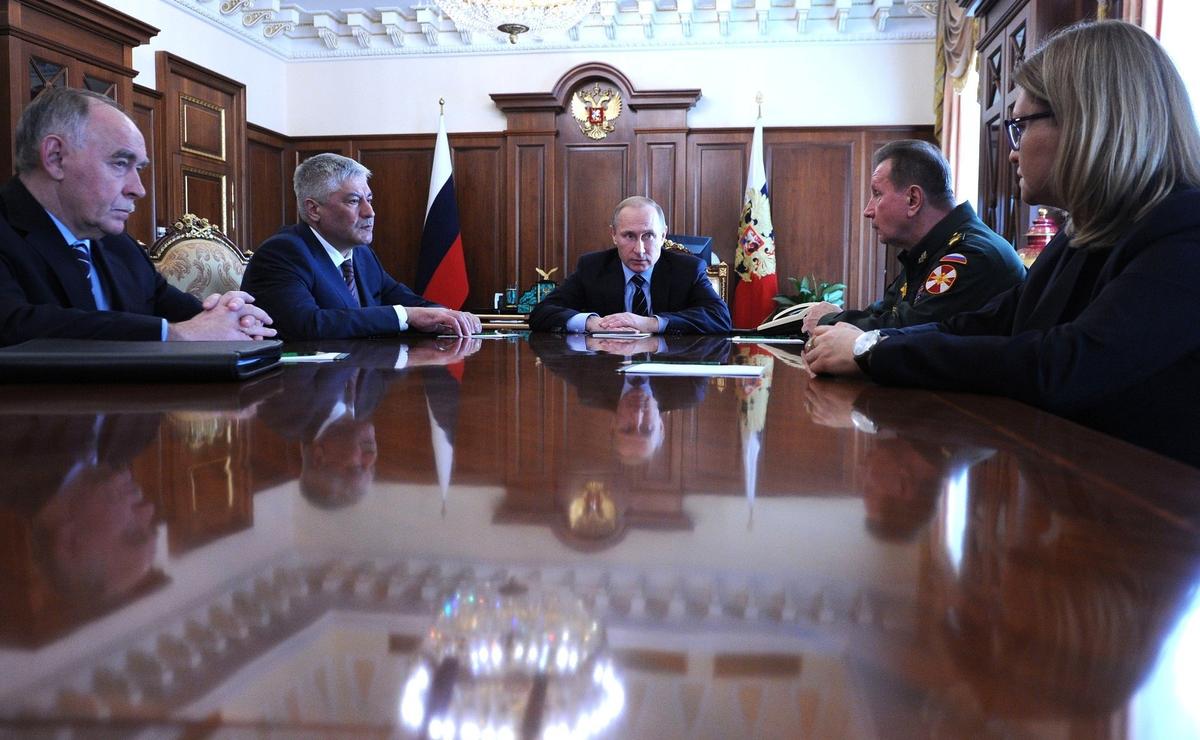

Director of the Federal Drug Control Service Viktor Ivanov, Interior Minister Vladimir Kolokoltsev, Commander of Internal Troops Viktor Zolotov, and First Deputy Director of the Federal Migration Service Ekaterina Egorova during a meeting with Vladimir Putin. Photo: Kremlin.ru

When the full-scale invasion of Ukraine started, Kolokoltsev once again attempted to add more personnel to the Grom special squad, doubling the number of its members. MP Alexander Khinshtein, who at one point was in charge of Zolotov’s PR, condemned Kolkoltsev’s actions in a 17 July post. According to Khinshtein, the Interior Ministry explained adding new members to the Grom squad by “the operational environment related to the special military operation”, which Khinshtein called an “unconvincing” reasoning. He even claimed that Grom would be passed over to the National Guard, however as yet it remains under the control of the Interior Ministry.

In a country at war, the lack of police response teams could lead to big trouble, the former investigator believes. And especially after the war — criminologists have shown that crime rates grow after soldiers return home from war, something that happened in the Soviet Union after its withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan.

“This won’t be like after Afghanistan. This will be a completely new situation, the likes of which no one has ever faced before,” he says.

“Who in the National Guard knows, for example, how to clamp down on the drug trade? Nobody,” the former investigator says, adding that any forces that might have been used to build such a force have been dissolved.

Petrov believes that fighting crime is not currently on the Kremlin’s agenda. Putin has no need for an effective security force, he just needs a loyal one.

Fiercely loyal

Zolotov began his tenure as head of the National Guard in 2016 by firing people. The National Guard had no place for anyone or anything that had ties to the now-defunct Internal Troops. Dozens of generals were forced to resign, with one even being jailed for fraud.

A National Guard armoured car during the Red Square Parade dedicated to the 73th anniversary of the Victory in WWII. Photo: Kremlin.ru

According to Petrov, the new high-ranking members of the National Guard, hand picked by Zolotov and likely even Putin himself, were appointed to ensure the National Guard would obey the Kremlin’s wishes without question.

The war in Ukraine does not appear to have affected Putin and Zolotov’s relationship. Even the failed June mutiny by the Wagner Group did not sour Putin’s attitude towards his former bodyguard. Miraculously, Zolotov even improved his reputation after the failed coup, referring to the response by security forces as “brilliant”, despite the National Guard’s failure to protect its patron from the mercenaries. Putin promised that its guardsmen would soon have access to military hardware as a mark of his gratitude.

“In some ways, the National Guard is Putin’s private army,” concludes Petrov. Putin put a “frankly incapable but loyal” man in charge of it — all part of a longer process to weed out any dissenters in the security forces.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]