Karin Kneissl, Austria’s former foreign minister, moved to a village in central Russia after a series of controversies and threats back home, a local news outlet reported. Kneissl’s case is not unique — over the centuries, many well-off Europeans and Americans who had to leave their home countries ended up in Russia. Today, we look at several such stories.

“Good evening. I only speak a bit of Russian. I now live in Petrushovo and I like the atmosphere,” Kneissl said in an address to the local villagers. She mentioned her desire to move to Russia for the first time during the St. Petersburg Economic Forum in mid-July, adding that she would have to learn Russian.

The statement was preceded by a nearly five-year-long affair with the Russian authorities, the most striking episode of which was Vladimir Putin’s appearance at Kneissl’s wedding in 2018, which caused mass outrage in the Austrian press. Kneissl did not deign to dispel suspicions of her ties with the Kremlin. In fact, she did exactly the opposite, becoming a columnist for RT in 2019 and joining the board of directors of Russian oil giant Rosneft in 2021. No official charges have been brought against Kneissl, but judging by the tone of the Austrian press, her political reputation in Austria is as good as ruined.

Kneissl’s journey from big politics in Europe to a village of less than 50 people (according to the 2010 census) in Russia may seem extraordinary. However, it is not particularly new: for hundreds of years, Europeans and Americans who had “sinned” in their homeland or were otherwise forced to leave often ended up in Russia.

Karin Kneissl in St. Petersburg. Photo: personal Twitter account

Ivan the Terrible’s police dog

One of the most quoted writings concerning the rule of Ivan the Terrible was authored by Heinrich von Staden, a fugitive from a family of wealthy German townspeople. As a teenager, he decided to follow the example of his older brother, a Catholic priest, and entered the seminary in his home town of Ahlen.

However, after allegedly stabbing a fellow seminarian, Staden fled to Livonia. There, he worked on the construction of the Riga city walls (which would soon be stormed by Ivan the Terrible’s troops), dabbled in trade, but in the end became a robber, pillaging towns and villages devastated in the Livonian War.

After several years of wandering, Staden crossed into Russia and persuaded Mikhail Morozov, ruler of the city of Dorpat, to send him straight to the Tsar’s court. Having won Ivan the Terrible’s favour, Staden joined the oprichnina — Russia’s first political police — and spent seven years studiously recording mediaeval Russian life, including the numerous atrocities committed by the Tsar against his people. By his own admission, Staden brought back fifty horses and two dozen wagons of loot from the oprichnina’s infamous terror campaign in Novgorod, during which thousands of people were killed.

After the Crimean Tatars burnt down Moscow in 1571 and the oprichnina dissolved, Staden, deprived of his Moscow property and income, tried to leave Russia, but failed.

He lived in northern Russia for several more years before finally making his way back to Germany.

Back in Germany, Staden compiled his notes into a detailed work, attached to it a plan for the occupation of Muscovy and his own autobiography, and sent it to the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II. Historians argue as to where and how exactly Staden ended his days. What they do know is that two other Germans who had served in the oprichnina and were mentioned by Staden in his notes — Johann Taube and Ehlert Kruse — eventually defected to Poland. A third German, Kaspar von Elferfeldt, failed to escape Ivan the Terrible’s grip: archaeologists unearthed his tombstone in the late 1980s during excavations just south of the centre of Moscow.

The mentor of Peter the Great

Religious wars and revolutions of the following century brought many foreigners to serve the rulers of Muscovy. Scottish Catholics who did not accept the fall of the House of Stuart and Cromwell’s rule played a particular role in Russian history.

Scottish aristocrat Paul Menesius (Menzies) was among the first mentors of Peter I. The English Revolution ruined the Menesius family, so Paul, the youngest son, had to make his own livelihood. Like many young Scotsmen at the time, he became a mercenary, fought in the Swedish army, then, in the midst of another Russian-Polish war, joined the Polish army.

Menesius was talked into travelling to Russia by Moscow diplomat Vasily Leontiev, who visited Warsaw in 1661 for peace negotiations. Menesius was accompanied by another Scotsman, Patrick Gordon, who would later find fame by becoming one of the founders of Peter the Great’s Guards Regiment. Upon their arrival in Moscow, the two found themselves in the midst of the Copper Coin Riot and helped Tsar Alexis to stay in power and punish the protesters, currying favour with the Tsar.

Gordon went on to build a purely military career, while Menesius, who spoke several languages, proved himself in the diplomatic field — he was sent as an ambassador to Europe to form an alliance against the Turks. After the European mission, the Tsar made Menesius a mentor to one of his sons — the future Peter the Great.

Young Peter’s portrait, late 1670s. Unknown author. Source: Wikimedia

“We do not know the details of how Menesius handled the prince, but it was he who sowed the first seeds of the ardent love for all things foreign that Peter had manifested since childhood,” writes historian Nikolai Kostomarov, adding that Menesius also kindled Peter’s fascination with military games, which later created the first European-style regular army in Russia.

After Tsar Alexis’ death, his daughter Sophia, who became regent, banished Menesius from the royal court and from tutoring the heir to the throne. Later, Peter himself returned his mentor to Moscow and favoured him in every possible way, granting him the rank of lieutenant-general. Unlike many foreigners in Russian service, Menesius stayed in the country until his death in 1694.

Interestingly, he was married to the daughter of another European in the service of Moscow — the Dutchman Peter Marselis, who became one of the founders of Russia’s metal industry.

Pushkin’s inspiration

After the French Revolution in 1789, more than 100,000 nobles left France, many of them ending up in Russia. Eugene Onegin’s tutor, Monsieur l'Abbé, “a starving Gaul”, as Alexander Pushkin calls him, embodies the collective fate of these French nobles — a fate shared by the poet’s real-life mentors, Count Montfort and Monsieur Rousselot.

There were truly exceptional people among those who fled France in the late 18th century. A significant part of them, having faithfully served Russia, returned home as soon as the opportunity presented itself. They include, for example, Armand Emmanuel du Plessis de Richelieu and Count Louis Alexandre Andrault de Langeron, who served as mayors of Odesa, or the painter Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, who created sophisticated portraits of members of the Romanov dynasty and introduced muslin dresses to the Russian court.

Portrait of Xavier de Maistre by P.E. Zabolotsky, 1840 Source: Wikimedia

The fate of the Savoyard Count Xavier de Maistre, brother of the famous conservative philosopher Joseph de Maistre, was different. He fought the French revolutionary forces as part of the army of the Kingdom of Sardinia, but hid in the mountains after their defeat. Deprived of all property by decree of the new authorities, de Maistre went into Russian service. He participated in the legendary Swiss campaign of general Alexander Suvorov, but, after a quarrel with him, de Maistre settled in Moscow and began making a living painting portraits. De Maistre gave us the portraits of the three-year-old Alexander Pushkin and his mother: perhaps we even owe him Pushin’s passion for writing poetry. Pushkin’s older sister Olga claimed that her brilliant brother decided to become a poet after hearing de Maistre recite his own verses.

Xavier de Maistre lived a long life, during which he wrote several books about Russia and translated major Russian authors into French. He died in Strelna, a suburb of St. Petersburg, in 1852, aged 88.

A Jamaican-Soviet engineer

In the 20th century, Westerners went to Soviet Russia not so much to flee from something, but to see for themselves what they thought a just society looked like. Such travellers included, for example, journalist John Reed, ethnographer Roy Barton, and aircraft designer Robert Bartini. Jamaican-born engineer Robert Robinson is an exception to this lineup, but his story is so striking that it is worth telling. In 1930, Robinson, a promising young mechanic at Ford’s Detroit plant tired of the pervasive racism in the US, agreed to a Moscow delegation’s offer to move to the USSR to help build up the Soviet industry.

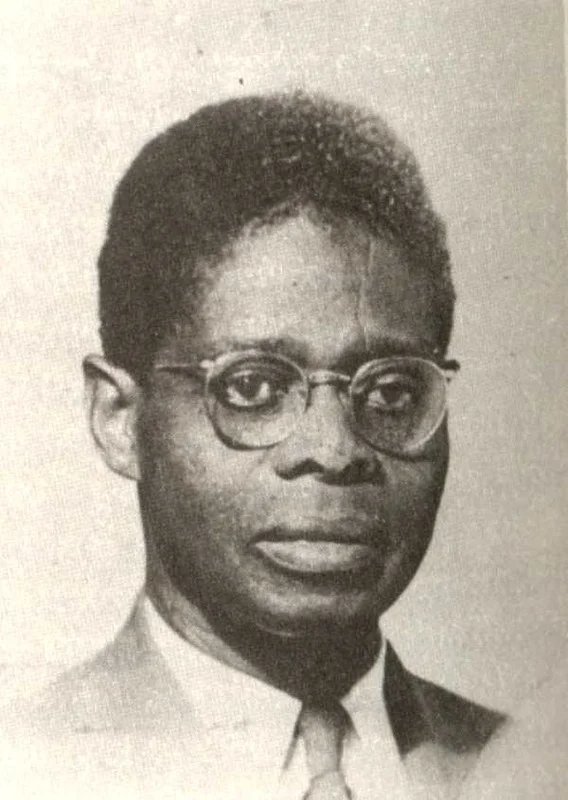

Robert Robinson. Photo: jamaicansabroad.weebly.com

Robinson lived in the Soviet Union for a whole 44 years and seemed to have received all possible favours from the Soviets: education, social status (Robinson was a deputy of the Moscow Soviet), interesting work and, on the whole, a trouble-free life. He even tried his hand at acting, starring in a film about the Russian traveller Miklukho-Maklai.

And yet Robinson escaped — applied for a trip to Soviet-friendly Uganda, evaded the vigilant control of his escorts and flew back to the United States. He lay low for 14 years, fearing that the long arm of Soviet power would reach him. Only in the late 1980s, when it became clear that the changes in the USSR were irreversible and he had nothing more to fear, did Robinson publish “Black on Red. 44 Years in the Soviet Union” — an autobiography that became an instant hit.

In it, Robinson partly paid tribute to the country that gave him a home, but also wrote in detail about Stalin’s purges, the constant fear (he knew seven African Americans who arrived in the USSR. All of them disappeared in the 1930s), and most importantly — the racism inherent in the Soviet people, which was even worse than the one from which he once fled.

“Racism constantly tested my patience and insulted human dignity,” Robinson wrote. “Since Russians boast of being free from racial prejudice, their racism is more cruel and dangerous than the one I encountered in my youth in the United States. I have rarely met a Russian who considered blacks — as well as Asians or any people with non-white skin — equal to himself. Trying to convince them is like catching a ghost. I felt their racism on the skin, but how can you deal with something that does not officially exist?”.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]