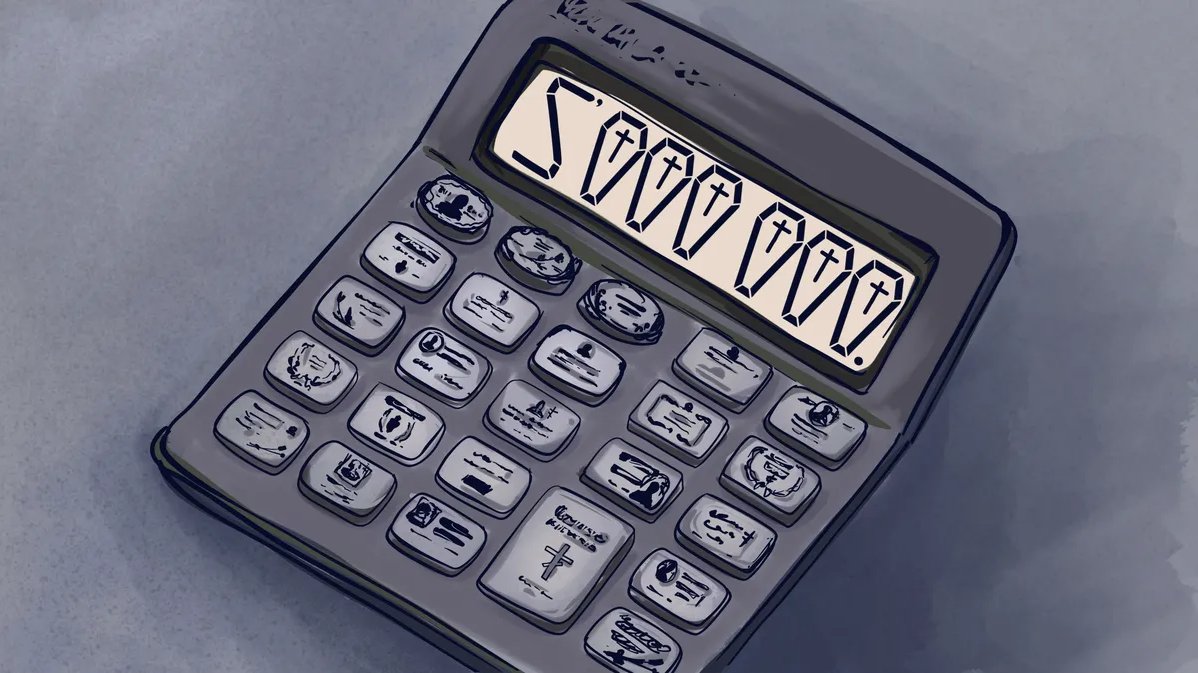

Russia may be spending as much as 850 billion rubles (€8.5 bn) a month on the war with Ukraine, according to some estimates. This incredible sum represents not only weapons and salaries, but also a vast array of social benefits for servicemen. Novaya-Europe has identified some 60 different allowances and non-cash benefits for servicemen and their families — four times what is currently offered to doctors or families. As a result, it is now more “profitable” for most Russian men to enlist in the army than it is to remain in the workplace. Has the Russian state really succeeded in making war a tool for social mobility?

Financial camouflage

As early as last year, when the 2023 federal budget was approved, it became clear that funding war, security, and state handouts remained the Russian government’s priority. While the sums spent on funding them have been disproportionately high for years, 2023 saw planned spending increase sharper than ever before, with the defence budget soaring by 42%, security costs by 26%, and “social policies” by 31%.

By contrast, year-on-year spending on education and economic development grew 13% and 11% respectively — an increase that was effectively written off by Russia’s 12% inflation in 2022.

This Kremlin largesse belies the fact that Russia is not really in a position to increase military spending: the 2022 budget has a deficit of 3.3 trillion rubles (€33 bn), despite being forecast to have a 1.5 trillion (€15 bn) surplus, and the preliminary budget for 2024 and 2025 are also both in deficit.

According to Ruben Yenikolopov, a professor at Moscow’s New Economic School, the projected military expenditure represents a lower estimate of war spending.

Firstly, these expenditures may hide only in the “defence” section, but also in the “economy” sector as expenditures going into the military-industrial complex or under “social policies” as payments to war veterans and their families, as well as in other sections of the budget. It is no coincidence that secret items account for 22% of the budget — more than 6 trillion rubles (€60 bn).

Typically around 15% of Russia’s federal budget is classified. The increased secrecy around the 2023 budget would suggest that classified items are being used to finance the military and maintain control over Russian-occupied territories in Ukraine.

The Defence Ministry’s actual spending may exceed the approved budget at the expense of other budget items. Yenikolopov notes that many items that do not appear to be related to the military actually are.

Current estimates of Russia’s war spending range from 6.7 to 10 trillion rubles (€67 bn to €100 bn) per year and are based on indirect indicators, making them somewhat speculative.

Military expert Pavel Luzin stresses the inadequacy of trying to assess the economic damage of the war in Ukraine by means of accountancy, and argues that it does not fully reflect the losses:

“War means lost income, loss of markets, loss of motivation to work, plan, and invest, rising costs, destruction of reputation, demoralisation, and a deep moral and ethical crisis. How can you measure that? You can’t.

This war has cost us much more than it may seem. And, no matter how things turn out, it will ultimately cost us even more.

Economist Sergey Guriev gives a rough estimate of the losses the Russian economy has experienced by comparing its forecast and actual economic data: claiming, for example, that in 2022, Russia’s GDP should have grown by 3%, but instead it dropped by 2%. The difference between these two figures is approximately 7.5 trillion rubles (€75bn).

Government handouts galore

Much like the vast expense allocated to the military and various other forces for protecting Putin from enemies domestic and foreign, Russia’s spiralling spending on social benefits seems like a poor investment in the country’s future. Economist Tatiana Mikhailova, a visiting professor at Penn State, calls this move “buying loyalty”.

Andrey Kolesnikov, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Centre in Berlin, is convinced that maintaining and strengthening the population’s dependence on the state is a fundamental element of Putin’s system.

“It has become a doctrine to keep the population in poverty so that they will be grateful for having their trousers held up by social handouts.”

During Putin’s time in power, the income received by Russians from entrepreneurial activity has dropped 2.5 times while that generated by state benefits has grown by 50% in the same period.

The fact that a huge part of Russia’s population lives below the poverty line and is dependent on state handouts has led to a situation where the payments offered for participating in the Ukraine war are mind-boggling sums that it would be virtually impossible to earn in any other way.

Sociologist and economist Vladislav Inozemtsev believes that the generous sums offered to those who enlist are the main reason why people are volunteering to go to war — and that this also explains why those who were mobilised or otherwise forced to go to war accept that and refrain from protesting.

A comparison of median salaries in different fields with that of an ordinary soldier shows that a father who has taken up arms can provide for his family much better than most civilians.

In addition to monthly salaries and lump sums for the families of those killed in combat, soldiers who served in the Ukraine war and their families are entitled to some 60 types of payments and non-cash benefits, according to Novaya-Europe’s research. This includes everything from regional payouts in case of injury or death (up to 3 million rubles, or €30,000) to pardons for convicts who have gone to war.

By contrast, Russian law provides only 16 types of benefits for families and 15 types of benefits for doctors (regular salary not included).

Moreover, Russia’s regions compete with each other by offering so-called “governor’s incentive payments” for those who enlist, increasing these payments, and even luring in potential contractors from neighbouring regions.

This is the only way to meet the requirements.

Inozemtsev warns of the risks inherent in the prospect of war becoming the most economically rewarding experience in the lives of many Russian men. It also seems unlikely that the money earned will be a significant contribution to their future well-being:

“Most of it will be spent on paying off loans, improving living conditions, some immediate expenses, a few months of a fairly prosperous life, after which they will have to face the reality, and it will be painful,” Inozemtsev says.

Death benefits

The most financially viable option for many Russian men is therefore to go to war, with their families standing to receive state benefits should they not return. Throughout Russia, a 35-year-old man who works until his retirement at 65 can expect to earn less in that time than the benefits the families of war veterans are eligible for.

Proving your death

Not everyone gets the exorbitant veteran payments promised by the state, though it’s hard to say if that’s due to bureaucratic chaos or a deliberate attempt to cut costs. Either way, thousands of Russians have not ultimately received the benefits they were promised, something made clear by the multiple accounts shared with blogs about the hardships faced by mobilised troops and professional soldiers alike.

We analysed 10,000 messages in one such blog and found 850 posts complaining about being denied a certain payout or receiving a significantly lower sum than expected. We did not include cases in which the delay in payment was negligible.

We also found that reports of being denied payments or receiving far less than expected applied to all types of payouts: salaries, compensation payments to the families of deceased soldiers, as well as various allowances and pensions, including survivor benefits. The number of complaints has increased with every month (data provided through 26 July).

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]