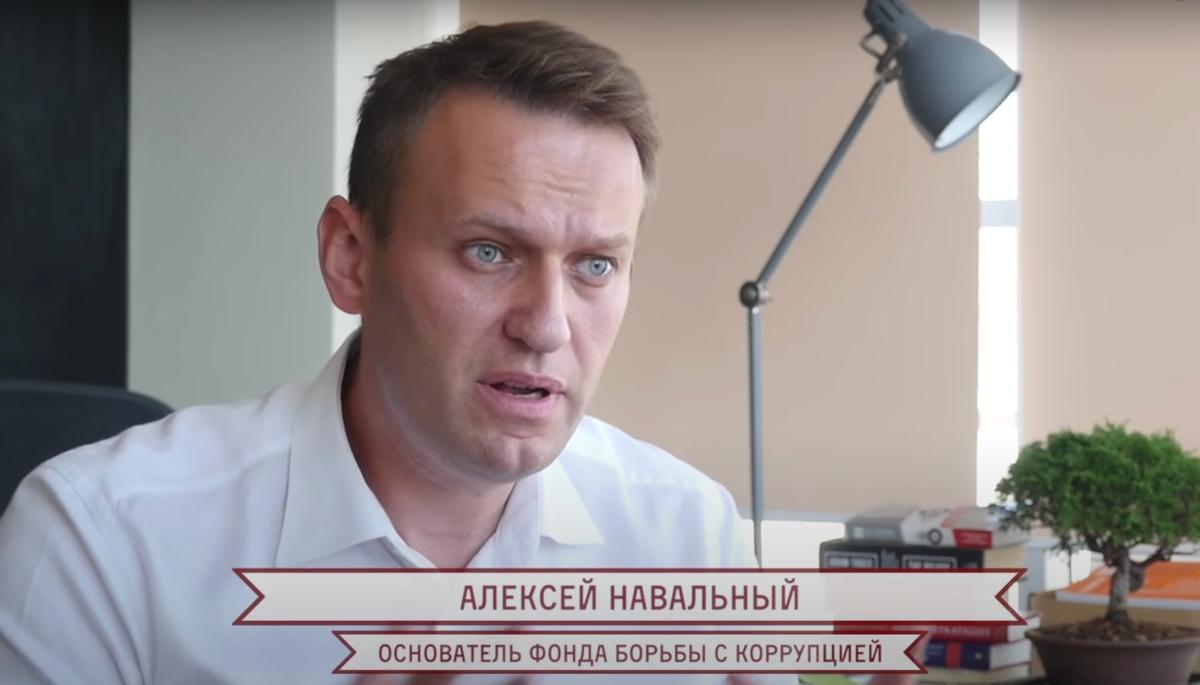

On 4 August, the Moscow City Court is expected to sentence Russian opposition politician Alexey Navalny on extremism charges. The prosecution has requested a 20-year sentence in one of the most restrictive types of prison. There is no doubt that the court will find Navalny guilty: he is a personal enemy of the Russian authorities and Vladimir Putin himself. The Russian President has never dared to call his opponent by name, although Navalny has repeatedly provided them with reasons to do so: over the past 10 years, his political career has taken many incredible turns. In 2013, Navalny was Moscow Mayor Sergey Sobyanin’s main rival and came in second in the mayoral elections. A decade later, Navalny finds himself the regime’s most famous political prisoner. In today’s photo gallery, Novaya-Europe looks back at some of the milestones in Alexey Navalny’s political life.

Photo: Wikimedia

2013. Navalny is running for mayor of Moscow despite having a criminal record following the first of many embezzlement cases against him. Found guilty and initially given a custodial sentence, Navalny was released the following day after a massive public outcry. Of course, it was impossible to pass the municipal filter — a special procedure that weeds out undesirable candidates — without the help of the authorities themselves, and they entertained his bid in the expectation that he would take the last place in disgrace. However, Navalny won over a quarter of the votes and Sobyanin only narrowly avoided a second round.

Photo: Mikhail Svetlov / Getty Images

After a fairly successful election campaign, Navalny focused on investigating corruption with his Anti-Corruption Foundation, or ACF (the authorities would later do everything they could to destroy the ACF and criminalise even its rank-and-file members. One of their first investigations led to the documentary Chaika about the businesses belonging to the sons of Yury Chaika, then Prosecutor General of Russia. While Chaika would soon move on to another position, his sons opted to have their names classified in all government registers, where they became the codenames LSDU3 and JFYAU9, which led to a slew of memes online. Photos: a screenshot from the Chaika documentary and Igor Chaika, son of former Russian Prosecutor General Yury Chaika.

Photo: Mikhail Svetlov / Getty Images

Don’t Call Him Dimon, an investigative documentary detailing the real estate and business assets of then Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev, became the Navalny team’s biggest success to date in 2017. Medvedev may have dismissed the investigation as “weird stuff, nonsense and some pieces of paper”, but the film sparked a wave of protests across Russia — primarily among young people. A Russian court ordered the film to be removed from YouTube, but it remains there six years later. A defamation lawsuit was filed by billionaire Alisher Usmanov, who, among other things, recorded a video message calling Navalny a “loser” and a “puppy barking at an elephant”.

Photo: Kira Yarmysh’s Twitter page

Of course, Navalny’s activities put him in considerable danger, and while the head of the Russian National Guard, Viktor Zolotov, contented himself with challenging Navalny to a duel and promising to make “mincemeat” out of him after one of his investigations, others took more radical steps. In April 2017, unknown assailants sprayed Navalny with brilliant green dye, damaging his eyesight. This was portentous and things would soon get far worse.

Photo: EPA-EFE / CLEMENS BILAN

In 2017, Navalny attempted to run for president, but his candidacy was unsurprisingly rejected, leading him to launch the Smart Voting strategy, inviting his supporters to vote for any candidate not from the ruling party United Russia. Navalny and the ACF received massive criticism for this initiative (since many politicians elected as a result went on to support the Ukraine war), but Navalny’s political influence was by now so great that the Russian secret services resorted to poisoning him with Novichok. In a later phone conversation with the poisoners themselves, Navalny found out that the nerve agent had been applied to his underwear. Luckily, he survived — in part because Putin ceded to international pressure and allowed Navalny to go to Berlin’s Charité hospital for treatment.

Photo: Andrey Rudakov / Bloomberg, EPA-EFE / YURI KOCHETKOV

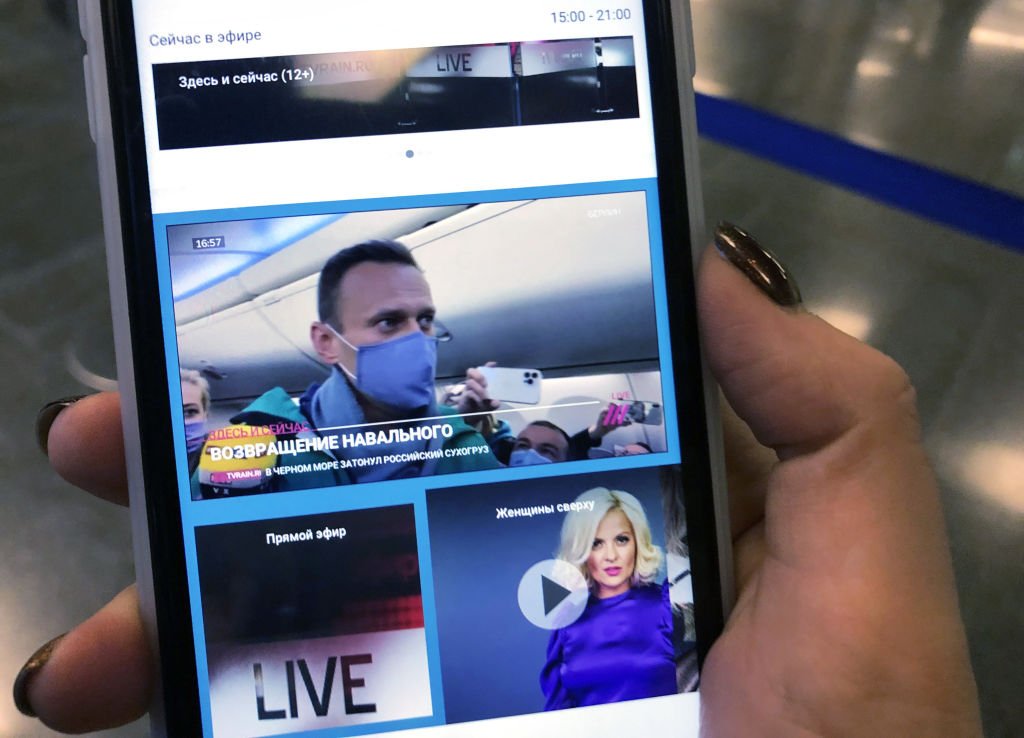

The unspoken rationale for allowing Navalny to go abroad was the belief that he would not come back — having been given a suspended sentence in a 2014 embezzlement case, the authorities found that his transfer to Germany violated the terms of his probation, meaning he could be arrested if he ever returned to Russia. Nonetheless, in January 2021 Navalny flew from Berlin to Moscow and was immediately detained upon arrival, sparking mass protests across the country. Despite the public outcry, Navalny was sentenced to 2 years and 3 months behind bars.

EPA-EFE/SERGEI ILNITSKY

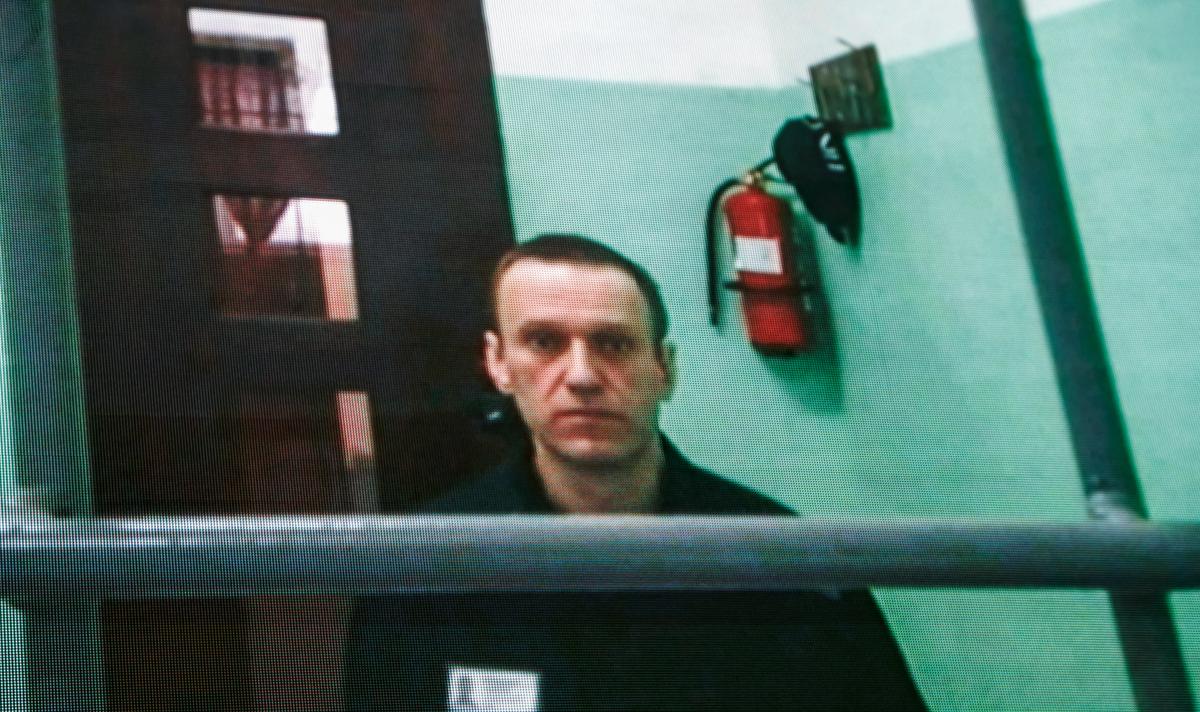

Since 2021 both the conditions of Navalny’s incarceration and the charges brought against him have become ever harsher. Nearly always kept in solitary confinement, Navalny has also seen his initial jail sentence of 2 years and 6 months be extended to 11 years after a guilty verdict in a case of fraud. In addition, Navalny now faces an additional 20 years in even worse conditions on charges of creating an extremist community.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]