What makes millions of Russians support the invasion of Ukraine? This question has many answers — from imperial ressentiment to the desire to absolve oneself of responsibility for war crimes. To understand the true beliefs of the ideological supporters of the war, Novaya-Europe analysed some 250,000 posts published on VK, Russia’s main social network. The results were unexpected: one of the most frequent arguments to justify the invasion was “striving for peace”. This article looks at how this paradox coexists in the minds of millions of Russians.

Reluctant support

In the first weeks after the invasion started, the behaviour of Russians on social media changed dramatically. The outbreak of hostilities was followed by laws introducing de facto war censorship. On 4 March 2022, the law on “fakes about the Russian army” was passed, introducing administrative and criminal liability for any information that could be interpreted as disapproving of Russia’s military actions. In the following two weeks, Meta, which owns Facebook and Instagram, was declared extremist and its websites were blocked in Russia.

All of this led to a marked change in the audience of VK, a social network closely monitored by Russian security services. Many opponents of the invasion left VK after the “fake news” law was adopted, leading to a sharp drop in the number of anti-war posts. Conversely, pro-war users began to use VK more frequently as a substitute for the blocked “extremist” social networks, and so the number of pro-war posts increased.

Researchers believe, however, that there is one more factor in this process that is not at all obvious.

Sociologist Sasha Kappinen, co-editor of the Public Sociology Lab (PSL) report on the Russians’ attitude to the war, draws attention to the dynamics of change in the number of pro-war posts compared to the number of anti-war posts in the first month of the invasion. It makes sense that the number of anti-war posts decreased after the new laws were passed, but the number of pro-war posts did not increase immediately after that.

“Many people who ended up being pro-war were in a state of shock in the first days and weeks after 24 February, having heard that the invasion had begun. Their support for the war was not automatic,” Kappinen says.

According to Kappinen, this shows that people were going through a severe internal conflict: the state demanded support for something that was morally unacceptable to them.

Both supporters and opponents of the war describe the same state of shock: “I couldn’t understand how in the 21st century my country could wage a real war — and against its neighbour at that”.

However, despite the similarity of the first reaction, the distinctive feature of the pro-war camp was that their original negative assessment did not become a political stance. It took them a while to get over the initial shock, but eventually they were able to find justification for the invasion and convince themselves that the state had done the right thing.

PSL’s report describes the ways in which many Russians dealt with this moral conflict. The graph shows that it took future supporters a month to digest what was happening.

As we can see, the assimilation of propaganda talking points is a two-way process, and not one-way as is commonly believed.

Narratives of war and peace

A significant part of the pro-war camp are, as the Re: Russia analytical project puts it, “conformists”. These people are rather apolitical, they do not “resist” the war, and they trust the state with all political decision-making. According to the PSL, such people often do not feel positive about Russia’s actions and may even disagree with some elements of its policy, but they are afraid to admit that Russia is doing something fundamentally wrong.

In our analysis, we looked at another category of war supporters (although it may overlap with the category of “passive” supporters): people from our VK sample endorse the war actively, have their own position on this issue, and find it important to express their viewpoint publicly in online posts. They probably do not make up the majority of the pro-war camp, but they are the ones who are ready to take action in support of the war: collecting money to buy weapons for the Russian military, writing denunciations, and, perhaps, even going to the front line.

So, what drives them? To find out their motives, we selected VK pro-war posts and analysed them by key themes (see the “Our methodology” block above). We did the same with anti-war posts.

Many of the results were to be expected: supporters of the war condemn “Ukrainian fascism”, make comparisons with the Great Patriotic War, talk about patriotism, freezing Europe, information-based warfare, and the shelling of Donetsk. Opponents of the war write about support for Ukraine, anti-war protests, political repression, sanctions, and the numbers of those dead and wounded.

Expectedly, both groups speak most of all about Putin’s role in starting the war (the pro-war camp supports him, while opponents of the war condemn him). In the personalist autocracy that Russia is, the absolute majority of people, regardless of their position, perceive the invasion of Ukraine as Putin’s personal decision and recognise his responsibility.

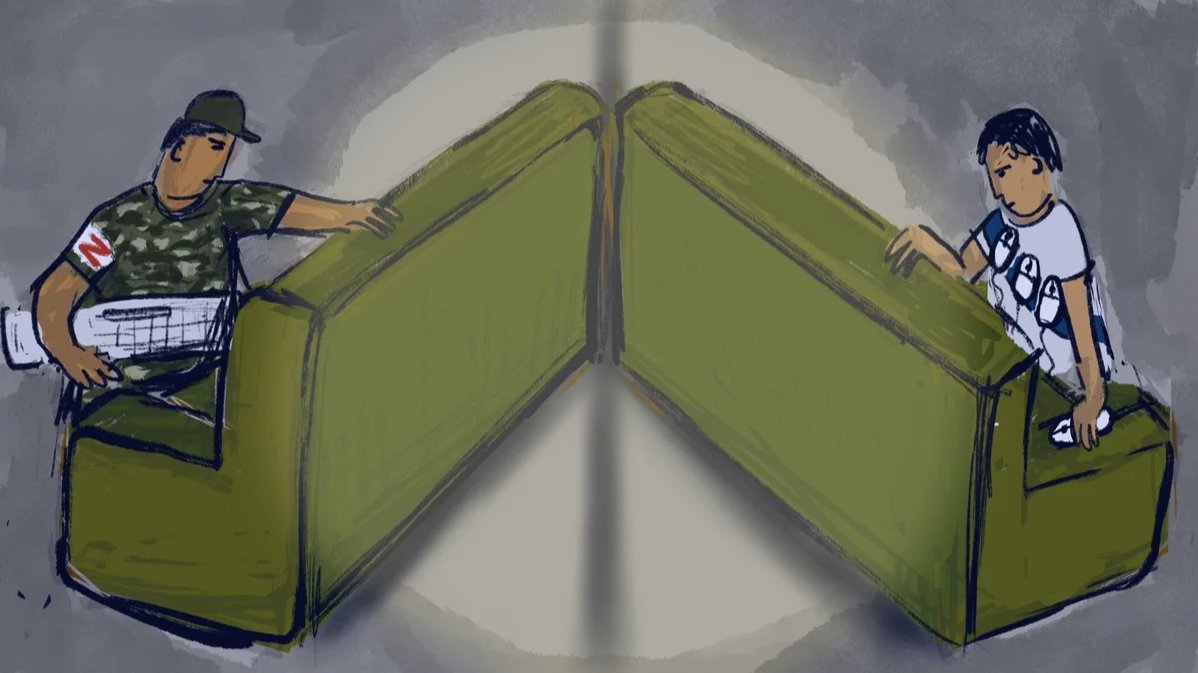

What was unexpected was that the second most popular narrative — the value of peace — was the same for both groups. The difference is that one group believes the war is distancing them from this goal, while the other group believes it is bringing them closer.

The peacekeepers’ paradox

“Stand together for freedom and peaceful skies!”, “Peace is the most important word in the world. Our planet needs peace”. Such posts could easily be mistaken for anti-war statements, if it were not for the hashtags. In the first case, the author accompanied their post with the hashtags#ForPeace#WeDontAbandonOurOwn#NotAshamed#WeStandTogether#TimetoHelp, and in the second case —#ForThePresident#WeDontAbandonOurOwn#RussianSpring.

In this context, the numerous arrests of people taking to the streets with peace posters take on a special meaning. As we can see, supporters of the war often talk about peace as well. This means that the true reason for the arrests are not the statements themselves, but the way they are being expressed — as a demonstration in the street.

In order to understand how supporters of war manage to use the value of peace as an argument justifying the invasion of Ukraine, we read several hundred pro-war posts about peace.

One of the arguments is that the war is necessary to achieve peace in Donbas: “The people of Donbass, who have lived for 8 years in horrible conditions — under constant shelling — finally got hope for a peaceful life!!!! We stand for Peace!!!” At the same time, the invasion is presented as a peacekeeping operation: “Russia continues its special operation in Ukraine, liberating its brotherly people from fascists, Banderites, and nationalists! In carrying out a peacekeeping operation, our soldiers are fighting for peace. We stand with you, Russian peacekeepers!”

“For many people, the war has become a challenge to their own moral image, to their belief that they are a normal and good person,” says Sasha Kappinen.

In an attempt to come to their senses and find a justification for what happened, future supporters of the war readily accepted state propaganda aimed at portraying Russia as a force for peace and justice. Kappinen points out that, before the Third Reich invaded Poland in 1939, Hitler and his acolytes had also worked to convince people that the attack was necessary by similar rhetorical means, saying that “our people” were being oppressed and must be protected.

Another popular meaning that pro-war VK users put into their statements about peace has to do with Russia’s security: “We stand for peace, for our country, for our sovereignty”. In such posts, the value of peace is mixed in with fear for one’s own safety due to external threats, usually from NATO: “It is a fact that Ukraine was preparing an attack on Donbass and Crimea with NATO support. Our president foiled their plans in time. We stand for peace!” Fear for one’s country should it lose in the war often leads to the conflation of peace and victory: “For the country! For the future! For peace!”

Some supporters of the war believe that the invasion of Ukraine is necessary to defeat Nazism: “In support of the Russian Army! For a world without Nazism!” This is obviously the influence of propaganda, which has been convincing people of the need to “denazify” Ukraine. Some VK posts portray Russia as a messiah who is meant to save the whole world from fascism:

“Today, our soldiers are not only defending our country, but they are standing guard over the world to prevent the revival of fascism,” “Russia has a historical mission — to save the world”.

Kappinen draws attention to the clichés that often crop up in the interviews that the PSL conducted with supporters of war: “I am against war, but…” After that comes the justification — for example that “there was no other way” and that the invasion was a reaction to the situation rather than the Russian state’s own initiative.

“The support we see is not unconditional. It comes with certain reservations. People have chosen to justify [the war] instead of approving of it because it allows them to maintain a balance: to believe themselves to be good people who are against murder and violence, but not to go against their state, instead supporting its aggressive policy,” Kappinen concludes.

An identity alternative

Paradoxically, even ideological support for the war uses the rhetoric of peace and safety as important values. Almost none of the pro-war VK users think that aggression and murder are normal, so they have to find excuses. Propaganda, in turn, plays on universal values, emotions and fears, offering people a way out: if you want to feel like this is meaningful — feel like you’re saving the world from Nazism. if you want safety and stability — that’s what the “special military operation” is for.

“In order to get mass support or non-resistance to such an objectively and obviously terrible action as war, propaganda needed to wrap it up in positive messages, to fill it with some palpable virtues that people supporting the war could relate to,” Kappinen points out.

This means that if the pro-war camp discovers another version of what is happening, while maintaining their self-image as a normal human being, their stance may change. This can happen both at the collective level as the sociopolitical situation and the media landscape change, and at the individual level — through communication with other people.

If the only idea that is offered to the pro-war camp is that they support crimes and will be held responsible for them, they will have little motivation to uphold this viewpoint — especially when the state narrative casts them either as peacekeepers or as victims of the “collective West’s treachery”.

“If you have not yet given up on these people (as many have done, which is understandable) and if you still have the desire or the need to sway them, then this is something you should definitely consider,” says Kappinen.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]