South Africa is set to host the 15th BRICS summit in August 2023. Leaders of the five members of this union — Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa — traditionally attend this event in person. However, the International Criminal Court (ICC) threw a spanner in the works for Russian President Vladimir Putin by issuing an arrest warrant against him on suspicion of committing war crimes in Ukraine.

South Africa is now trying to find a way out of this mess, balancing between the desire not to offend Moscow and Putin personally and the responsibility to uphold its international obligations assumed under the Rome Statute that established the ICC. South African President Cyril Ramaphosa will likely attend the Russia-Africa summit in late July to find a possible compromise for all parties involved. Alternatively, rumours suggest that the BRICS summit can potentially even be moved to China.

Novaya-Europe spoke to South African experts to get a handle on the situation: what’s happening in the country now, will Putin be able to attend the summit, and what influence can the US and the EU wield over Pretoria.

The jaw-dropping report that the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued an arrest warrant against Vladimir Putin on suspicion of being involved in the illegal deportation of children from Ukraine put South Africa in a real pickle. The country will host a regular BRICS summit in August 2023, which all the leaders of the bloc are expected to attend, including the Russian president. However, South Africa is a signatory to the Rome Statute — an international treaty that established the ICC — which means that the national authorities will be legally bound to detain Putin immediately after he disembarks from his plane and extradite him to the Netherlands.

This is why a very mundane event that rarely attracts much attention outside of the union’s member states suddenly occupied a top spot on the international agenda. The stakes are getting higher by the hour for all interested parties.

For Putin, this summit will serve as a brilliant opportunity to defy the international community by showing the world that the recent attempts to isolate Russia have failed. For the ICC, it is a test of its authority

— otherwise, what’s the point of an international body if member states turn a blind eye to its instructions.

The West is looking forward to the summit as a great chance to bring the man who ordered a full-scale invasion of Ukraine to justice. Meanwhile, South Africa is seemingly trying to pass an equilibristics exam: will the country manage to maintain its ties with Russia without ruining its international reputation?

Pretoria’s headache

The most accurate word that comes to mind when trying to describe South Africa’s reaction to Putin’s potential arrival in the country as a person wanted by the ICC is turmoil.

On 19 March, almost immediately after the arrest warrant was issued, spokesperson for the South African president Vincent Magwenya said that the government “will remain engaged with various relevant stakeholders with respect to the summit and other issues related”. On 23 March, Foreign Minister Naledi Pandor confirmed that Putin had been invited to the event, adding on 24 March that Pretoria is expecting “a refreshed legal opinion on the matter” but “continues to be a member State of the Rome treaty”. At the same time, Pandor lamented that the ICC is exhibiting “double standards”.

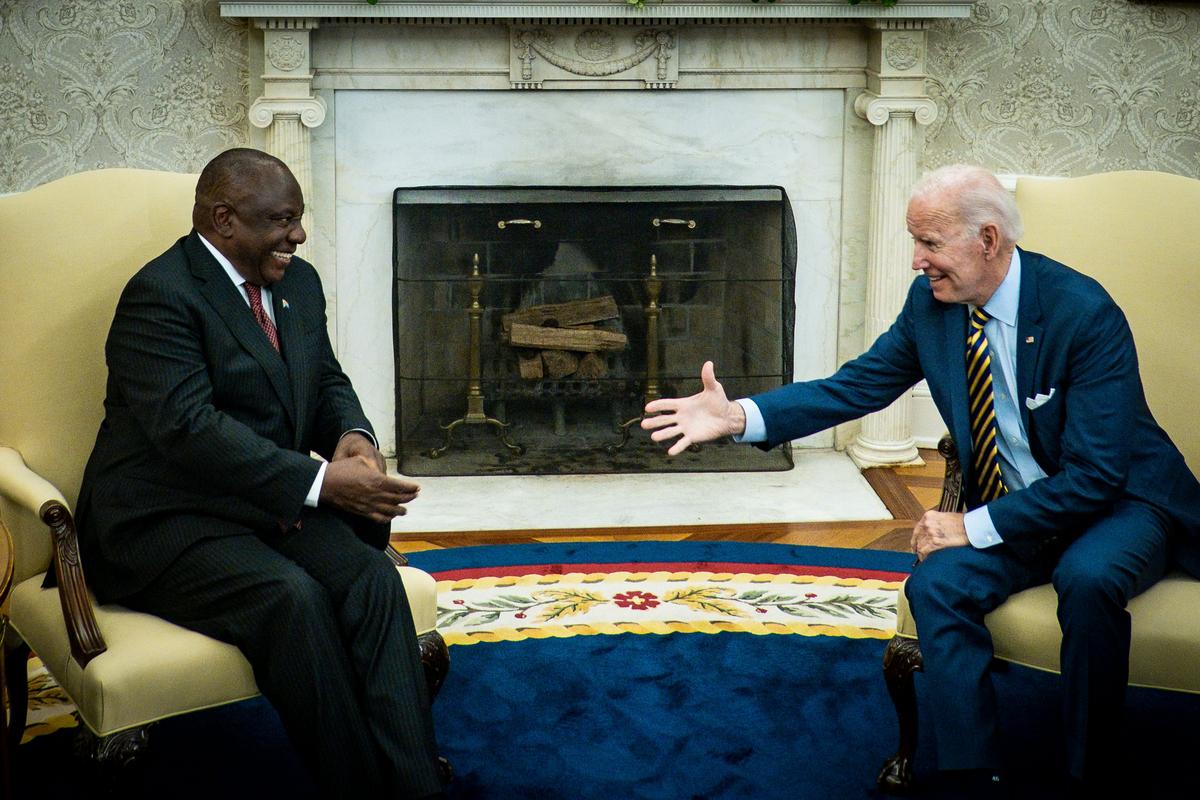

Cyril Ramaphosa. Photo: EPA-EFE/OLEG PETRASYUK

The havoc intensified further after Cyril Ramaphosa announced on 25 April that South Africa would quit the Rome Statute. This puzzling statement was met with an even more puzzling reaction: a few hours later Ramaphosa’s office published a rebuttal of the announcement, stating that it was “an error”.

Eventually, South Africa’s Foreign Ministry issued a brief statement noting that all members of the BRICS ministerial meeting and leaders’ summit would be granted diplomatic immunity. The agency claimed that it is “standard procedure” for all international conferences and summits irrespective of the level of participation. However, the Democratic Alliance, South Africa’s main opposition party, queried the decision and put out a statement on 31 May, containing a confirmation from the foreign affairs agency that the “diplomatic immunity will not apply to Putin and his arrest warrant remains enforceable”. Moreover, senior official Obed Bapela told the BBC that the government intended to change national laws to independently decide whether to arrest anyone at the ICC’s request. “In June, we’ll be submitting the law in parliament,” he pledged. However, no motions have been tabled in the national parliament as of yet.

Amid this political and diplomatic upheaval, various media outlets published stories, shedding light on behind-the-scenes negotiations going on between Pretoria and Moscow. The Sunday Times, for instance, reported that the South African government had asked Vladimir Putin to stay away from the country and the summit, opting to take part in it via Zoom instead.

“We have no option not to arrest Putin. If he comes here, we will be forced to detain him,”

one of the sources told Sunday Times. Reuters later noted that the summit can even be relocated to China to avoid following through with the ICC arrest demand.

The Kremlin is traditionally mum on Putin’s plans. According to spokesman Dmitry Peskov, a master of making statements without saying anything of value or substance, the decision on the Russian president’s trip to South Africa was “yet to be made” but the preparations were “going ahead as planned”.

Peskov later added that “Russia will take part in the summit with the appropriate level of participation”. If we look back at the 2022 G20 summit, which was held in Indonesia, we can expect that any official announcement regarding Putin’s travel plans will come right before the BRICS summit is supposed to take place.

Back in 2022, months of speculation whether the Russian leader would personally fly to Bali ended when Peskov told the press that the Russian delegation would be headed by Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov. The situations are not the same, however: BRICS is a club of much more closely aligned states than G20 and Putin’s motivation to attend it in person is much higher now.

Friendship against the West

Despite the fact that Vladimir Putin’s brand has turned especially toxic lately, Russia’s BRICS partners are not rushing to renounce the alleged war criminal. For example, Chinese leader Xi Jinping travelled to Moscow for talks recently. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi chaired a Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) meeting attended by Putin and Xi and met Russia’s security council chief Nikolay Patrushev in New Delhi (even though press reports suggest that he cancelled his in-person meeting with Putin in December 2022). Brazilian President Lula da Silva recently had a phone call with his Russian counterpart, where, truth be told, he declined to attend Putin’s flagship SPIEF economic forum in St. Petersburg, but confirmed that he is ready to speak with both sides of the Ukraine conflict.

As for South Africa, no significant (or any at all) cooling of ties can be currently observed. On the contrary, Pretoria did not back a single UN resolution criticising Russia’s actions in Ukraine, the South African defence minister flew to Moscow for bilateral talks in August 2022, a delegation of the country’s ruling party exchanged experience with United Russia, while Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov has already visited South Africa twice in 2023.

Russia’s Admiral Gorshkov frigate making its first long-range voyage with a Zircon hypersonic missile loadout as part of trilateral naval drills between Russia, China, and South Africa. Photo: video screenshot

The event that drew the most attention, however, was the trilateral naval drills conducted by Russia, China, and South Africa in the Indian Ocean, near Durban, on 17-27 February to somewhat mark the anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Steven Gruzd, head of the Africa-Russia project at the South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA), does not see the exercises as serious and large-scale in any sense but is certain that “South Africa used them as an opportunity to say, ‘We have an independent foreign policy, we are allowed to choose our friends and our enemies, we won’t let you choose our friends and our enemies, and we will decide what we do as a sovereign state’”.

The ideas of “anti-colonialism”, fighting against the hegemony of the “golden billion”, and “the West’s dictatorship”, which Moscow has been promoting for quite some time now, also resonate with South Africa. Since the Ukraine war began, these theories and ideas gained a new dimension, while Putin’s speech delivered at the official ceremony of annexation of four Ukrainian regions in September 2022 made it clear that the Kremlin will now position itself as a new and appealing leader in place of the “selfish and greedy collective West”.

“Those arguments that Russia makes about a fairer world, a multipolar world, have a lot of resonance in South Africa, they land on fertile ground here,”

Steven Gruzd is certain. “South Africa genuinely seems to see Russia as an ally for reforming the global international system. Now, whether Russia is sincere about that, that’s the question.”

Pretoria’s admission to BRICS in 2010 was largely a continuation of the country’s foreign policy of multilateralism and multipolarity. “The BRICS countries are all projecting an anti-colonial and anti-imperial ideological stance in world politics and the South African government echoes these sentiments in its foreign policy,” says Theo Neethling, Professor and Head of the Department of Political Studies and Governance at the University of the Free State. South Africa also seeks to reform the global system of governance — the UN Security Council, IMF, and World Bank. To achieve these goals, the country needs allies. This is one possible explanation why South Africa refuses to distance itself from Russia and Putin that has driven Pretoria to the current ICC conundrum.

The historical ties to Russia also add weight to this stance: the Soviet Union was actively involved in supporting the liberation struggle of the black population during the apartheid times in South Africa. The Conversation writes that Moscow was heavily backing the African National Congress (ANC), initially a liberation movement turned into a political party that has ruled South Africa for close to 30 years now, both financially and militarily. These efforts represent Russia’s contribution to the eventual fall of apartheid, which many ANC officials still remember.

Viktor Vekselberg. Photo: SPIEF

If not, their memory was refreshed by a hefty donation of $826,000 to the ANC received from a mining company associated with Russian oligarch Viktor Vekselberg. “Viktor Vekselberg has been linked to the ANC before; this is not the first time his name has come up, and this is a sizable donation to a very cash-strapped political party,” Steven Gruzd told Voice of America. Daily Maverick, a local South African newspaper, claims that “the relationship with a supposed Kremlin insider is key to party finances”, since this mining company “is arguably the largest single source of declared funding for the governing party”.

According to Bloomberg, at the summit, the BRICS leaders will discuss the club’s potential expansion and establishment of a single currency “to counter the US”. So, if the Ukraine war and Putin’s ICC arrest warrant had any impact on the harmony and unity of BRICS, the general public is yet to see it.

Support independent journalism

Omar al-Bashir 2.0

It’s not the first time that South Africa finds itself in an ICC-related stalemate. Back in 2015, the country hosted an African Union summit and received Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir, who had been wanted by The Hague court since 2008 on genocide charges thar emerged following the War in Darfur where ethnic cleansing operations reportedly took place.

Coincidentally, al-Bashir became the first sitting president to be indicted by the international court. He was invited to attend the summit despite the protests of South Africa’s civil society, activists, and human rights organisations.

The administration of then-President Jacob Zuma defended its actions by saying that all the event participants enjoyed diplomatic immunity protecting them against any law enforcement-related repercussions as officially invited guests. The ICC, in turn, insisted that immunity of any person slapped with an arrest warrant is suspended immediately, irrespective of whether their own country ratified the Rome Statute.

In the end, al-Bashir successfully evaded detention during his trip to South Africa and left the country after the summit.

Activists filed a lawsuit against the government for failing to honour its international obligations and won the case in two different courts. In 2017, ICC judges ruled that Pretoria had erred by letting al-Bashir leave the country a free man. The ruling in itself creates a precedent but also lays bare a very significant problem with this international institution’s jurisdiction: the ICC is fully dependent on its signatories to exact justice. The South African Institute for Security Studies (ISS) then wrote that “the judgement is important — not only because it raises questions about South Africa’s role in international justice — but because of what it says about the weak tools in the ICC’s arsenal to ensure cooperation by states”.

Fast forward to 2023, and Pretoria once again tried to use the diplomatic immunity defence strategy to welcome Putin for the BRICS summit. However, the public pressure seemingly forced the government to backtrack on its move and add that Putin would not be covered by this immunity. Nevertheless, Steven Gruzd believes that South Africa will once again come up with a way out of this deadlock and save its face as much as possible: “My suspicion is he [Putin] will come. But there will be some kind of deal made, somehow. And I don’t think he will have the embarrassment of being arrested in South Africa. But there may be legal challenges. Again, I think civil society will mobilise, and there might be another lawsuit”.

Theo Neethling also believes that the Russian leader will not be arrested if he chooses to arrive in South Africa in person. However, he thinks that “Putin might be convinced to attend online or even be represented at the BRICS summit by [Russian Foreign Minister] Sergey Lavrov”. The issue here is that Pretoria will need to strike a balance between its ties with BRICS and relations with the West. First and foremost, because South Africa should take care of its trade relations with the EU, the UK, and the US.

Joe Biden and Cyril Ramaphosa. Photo: EPA-EFE/Pete Marovich

Blackmail tool

The US and the EU hold a very powerful instrument to wield influence over South Africa: trade. The volume of foreign trade between South Africa and the US reaches $21 billion. At the same time, Pretoria enjoys the benefits of the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), which gives the country privileged access to the American market and several other advantages. South Africa’s trade with the EU is valued at €55.56 billion. In comparison, Russia is only able to offer a trade volume of $1.3 billion a year to South Africa.

Back in February, amidst the Russia-China-South Africa navy exercises, the US already announced that it might review its trade relations with Pretoria. Moreover, the US ambassador openly accused the country in May of supplying arms and ammo to Russia. According to him, the transfer was conducted at a naval base near Cape Town where a Russian ship was docked. “The arming of the Russians is extremely serious, and we do not consider this issue to be resolved, and we would like SA to [start] practising its non-alignment policy,” the envoy lamented.

In response, President Ramaphosa vowed to get to the bottom of the situation and put together a commission to investigate the incident, while his spokesperson publicly slammed the US diplomat for a hasty statement made in violation of an agreement reached with the White House, allowing the investigation to run its course. The New York Times notes that the South African rand accelerated its drop in value against the dollar following these accusations.

Pretoria then announced that the US envoy allegedly apologised for his comments. A few days later, South Africa revealed a plan to send a pan-African delegation to Moscow and Kyiv to offer the continent’s vision of a potential peace treaty that will end the bloodshed. This sequence of events seems too good to be coincidental.

According to Steven Gruzd, South Africa enjoys great privileges in international relations as one of the key players in Africa. “Frankly, I think South Africa is allowed a lot of space in the international community to do things that the West doesn't like,” he says. “[These] relations may be tense with the West, but they would never risk severing these relations.”

“And I think also, sometimes, we find that the more [Western] Embassies push that they don’t like it, the more South Africa [turns] towards China and Russia. So the more pressure that’s applied, especially if it’s just verbal pressure, the more South Africa digs its heels in.”

Nevertheless, the West has all the tools to make South Africa regret its alliance with the Kremlin and force the country to comply with its international obligations as an ICC member. Even more so now that Pretoria is already heavily chastised by its global partners and opposition forces from inside the country for its desire to avoid any criticism of Moscow for the war it unleashed on Ukraine at any cost.

This means that the decision on how to deal with South Africa if Putin arrives in the country for the summit lies with Western capitals. The only question here is whether they are willing to act swiftly and decisively.

Translated into English by Alexander Gorsky

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]