Over 25,000 Ukrainians, including 20,000 civilians, have been listed as missing since 24 February 2022. Russia is trying to swap kidnapped civilians for its servicemen captured in combat. But this strategy is a dead end — no one wants to exchange civilians for soldiers. On occupied territory, anyone can become Russia’s hostage.

“The Russian Federation is obliged to return them unconditionally and not include them in the POW exchange process,” said Dmytro Lubinets, Ukraine’s human rights commissioner. Novaya-Europe tells two stories of such kidnappings.

THE FIRST STORY

Last call

“When the war started, my parents and my 14-year-old sister lived in the town of Oleshky in the Kherson region,” Victoria Barabash recounts.

Victoria’s dad, 50-year-old Serhiy Kotov, worked as a driving instructor. “He was a local activist: he often criticised the authorities for bad roads, for instance. He had respect among the townspeople. Many people approached him with various problems.”

At around 6 AM on 7 April 2022, five large military vehicles drove up to the Kotovs’ house and surrounded the yard. Serhiy had just stepped out onto the porch for a smoke; his wife and younger daughter were still asleep. He saw armed soldiers in balaclavas climbing from his neighbours’ plot through the bent iron fence. At the same time someone was knocking loudly on the gate. Kotov opened it, and several more armed men in masks, huge shields in their hands, entered the yard.

“They behaved politely, one might say. They did not hit my father at this point,” continues Victoria.

“They took away my parents’ phones, put all the family members into different rooms, and searched the house. All the while, armed men were watching every move of my mum, dad, and sister. Then, they questioned everyone individually. Afterwards, my mum got her phone back. I don’t know if they found anything in dad’s phone, but after the interrogation they took him away, telling him to take his passport and medication — dad has to use crutches because of his leg problems. Mum begged to let him go, but was told: ‘You see that we are not like other Russians, we don’t rob, we don’t beat you, we don’t rummage through your fridge.’ One of them gave an ‘officer’s word’ that they would have my father home by evening.”

Kotov’s wife was told to keep her phone handy and wait for a call. The next evening, Serhiy was allowed to call his family on speakerphone. His voice was different — frightened. He spoke to his wife, then asked to put his youngest daughter on the phone. That same evening, he also called his eldest daughter, Victoria. That was the last time the family spoke to him.

“He said then that he’d had a seizure and was on an IV drip, so that’s why he didn’t call yesterday,” Victoria recalls. “But you could hear in his voice that it wasn’t true. He was just reassuring us. I asked: ‘Dad, did they beat you?’, and he hastily said no. We never heard from him again until mid-August of last year.”

After this strange phone call, the family waited for another week, and then his wife and daughter left for territory under Ukrainian control. Once they were safe, they immediately started writing to the Ukrainian authorities. The prosecutor’s office even opened a criminal case, filing Kotov as a missing person. The family also appealed to the Russian-appointed “authorities” in the region, but there was no response. Before leaving, they did not dare make any inquiries, fearing what the Russian military might do to them.

Four months later, in August, Kotov was able to send word to his family through a cellmate. Once this man was free, he immediately informed Kotov’s eldest daughter that her father was in a pre-trial detention facility in Simferopol. To ensure the family would believe him, the caller told them a story that only they and Kotov could know.

After finding out that Serhiy Kotov was in the Simferopol detention centre, the family tried to hire a Crimean lawyer, but, according to Victoria, they were only scammed.

Shortly before the New Year, the family received a call from another man, Ivan (the name has been changed for safety reasons). He has also been in the same cell as Kotov, and Serhiy passed a letter for his family through him. Ivan was detained immediately after leaving the pre-trial jail and had to throw the letter out, but he had managed to learn it by heart. He was taken to another prison and released a month later. That was when the Kotovs found out exactly where Serhiy was and what had happened to him.

“In mid-January 2023, we made an agreement with the lawyer who [had] worked on the release of Ivan,” Victoria says. “Everyone told us that it was pointless, that Russians never release detained Ukrainians, but we know that there have been positive results.”

Almost a year after Kotov’s arrest, in March 2023, the family finally received the first official paper: the prosecutor’s office of the Russian Navy confirmed that Serhiy Kotov was arrested “in connection with countering the special military operation” and placed in a pre-trial detention centre, but did not indicate which one.

“After that, I started writing again to the National Information Bureau of Ukraine, to the coordination headquarters, to the Security Service, saying that my father was being held captive, but the response once again was that the aggressor country has not confirmed his detention,” Victoria explained. “I don’t know if they really made any inquiries, because the impression is that nobody bothers with civilians now.”

Serhiy Kotov before the war. Photo courtesy of Kotov’s family

On 11 May 2023, a court in Simferopol arrested Kotov officially for the first time — for two months. He was accused of espionage, and a criminal case was opened.

Immediately after his “arrest” for alleged espionage, the authorities tried to impose a public defender on Kotov, but his own lawyer thankfully managed to get through. The two were able to talk through the glass before the judge arrived.

Kotov told the lawyer that he was severely beaten in Kherson, lost consciousness, and then beaten again when he woke up. The tormentors wrapped a bag around his head and took him to be shot. They fired a machine gun near his ear, leading to a concussion and constant tinnitus.

Serhiy Kotov in a Russian jail. Photo courtesy of Kotov’s family

While under arrest, Kotov became infected with hepatitis C. He suffers from chronic pancreatitis, and his injured leg is rotting. Before the war, he had surgery after a compound fracture and got an infection. To keep the bone from rotting, he has to take medication all the time, but of course he is not given any in prison.

His lawyer asked the court to change Kotov’s form of detention, but the judge decided against it, saying that the detainee could flee abroad.

Kotov’s former cellmates told Victoria that the food in the pre-trial jail is very poor and her father keeps losing weight. He tried to exercise, but sports are forbidden in the detention centre. Kotov, who has always been a heavyset man, has lost over 20 kilograms (44 pounds). Before the war, he did sports and excelled at the bench press, even earning the title of International Master of Sports.

During the search, the Russians found nothing on Serhiy’s phone. But a search of the phone of Kherson resident Mykola Petrovsky revealed he and Kotov had been messaging each other, with the latter forwarding information about the movement of Russian military equipment. Victoria says the lawyer harbours no illusions and is convinced that his client will stay in prison. The hope is to have Kotov’s sentence reduced based on his health issues and then try to include him in the exchange fund.

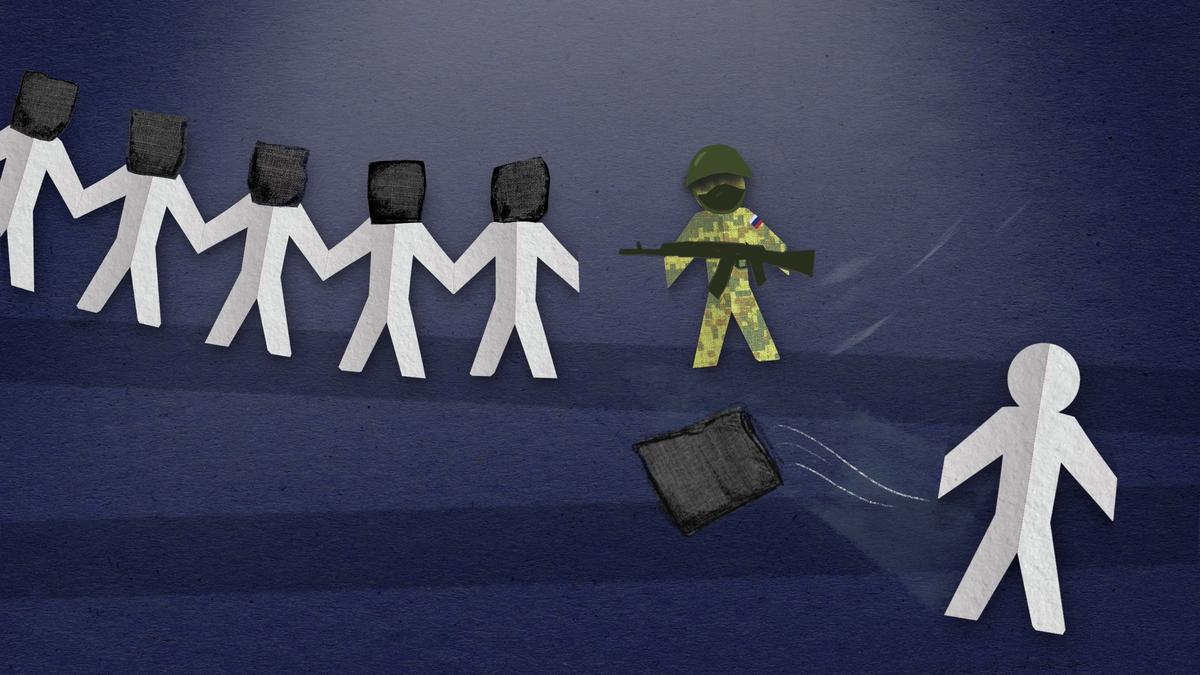

Illustration: Alisa Krasnikova / Novaya Gazeta Europe

THE SECOND STORY

Caught on the border

Ivan, who passed Kotov’s message on to his family, is now free. His story is rather miraculous: it is rare for a kidnapped Ukrainian to go free. Last July, he and his parents wanted to travel to Europe via Crimea and Russia. On crossing the makeshift border, 23-year-old Ivan was sent to undergo the so-called “filtration” — a conversation with an FSB officer. To this day, those who have never crossed this border (mostly men) are interrogated in a special booth near the checkpoint, their phones are checked, and their passports are taken away.

They connected Ivan’s phone to a laptop and restored all deleted media files using a special program. “Have you been filming Russian military equipment?” was the first question, and Ivan realised that the agent already knew everything. At the beginning of the war, he had indeed been filming the Russians passing through his village and handing the recordings over to the Ukrainian army.

Ivan was brought to the FSB office in Armyansk (Crimea), where he was held for three days and then taken to Simferopol.

His parents waited for him in Simferopol for another month. They went to the FSB office almost every day and were told that their son would be released soon. At some point, the parents realised they were being lied to and hired a lawyer. Only then did they return to their home village.

‘That’s how they joke around’

“On 1 August [2022], I was transported to Simferopol, and the next day someone from the FSB interrogated me for the first time,” Ivan recalls. “We chatted, and he said that everything was fine, that I would be taken to another place and do a polygraph test three days later. That’s when they put a cap over my eyes, duct-taped my hands together, and put me in the boot of a car.”

That is how Ivan was brought to pre-trial detention facility no. 1 in Simferopol. The agent treated him carefully, telling him where to bend down so as not to hit himself and pointing out where the steps were. But as soon as he handed Ivan over to the detention facility staff, they immediately twisted his arms till his head was at knee level and frogmarched him inside.

“They told me to undress completely without removing the cap from my eyes. I managed it somehow. Then they ordered me to get dressed. As soon as I got dressed, I received a heavy blow in the stomach. And again…” After the beating, Ivan was once again taken somewhere.

The pre-trial jail in Simferopol. Photo: Yandex maps

“They took me up and down the stairs. They would take me into a corner and beat me. They also beat me on the way. Then they led me somewhere again. They took me to some officer (a young man, by the sound of his voice), who was profiling all the detainees. They put me on my knees and told me not to move around.”

The officer asked Ivan the standard questions: surname, place of registration, place of residence, passport details, age... He also inquired about political views and asked why and under what circumstances Ivan was arrested.

“At some point he saw that it was difficult for me to stand on my knees and allowed me to stand up, and after another ten minutes allowed me to sit down on a chair. Almost immediately after that someone came into the office and started hitting me for sitting down. Must be how they joke around.”

After the interrogation, Ivan was given a pen, and his hand was held to the spot where he was to sign. He could not see what he was signing as he still had the cap pulled over his eyes.

The next place Ivan was brought to was the medical office. There he was examined, had a blood sample taken, and was again told to sign something — all this while blindfolded.

Kotov’s cellmate

Ivan was told how to prepare for officers’ visits: when they knocked on the door of the cell, he had to quickly assume the so-called “dolphin pose” (legs wide apart and torso parallel to the floor, arms halfway behind his back), facing away from the door. As soon as the order is given, one must swiftly run out into the hall in this position. The main thing is not to look at the faces and into the eyes of the staff.

“When I was led into the cell, they finally took off the cap but told me not to turn towards the door until the staff members had closed it behind themselves — all so as not to accidentally see their faces”, Ivan explains. “God forbid you glance at them — you’ll be severely beaten.”

Ivan was alone in the cell. Exhausted, he quickly fell asleep. The next day he was fingerprinted, videotaped, and photographed.

“There were two categories of guards there,” Ivan recalls. “There were the colony staff who wore blue police uniforms — you were allowed to look at them, though that was also unwelcome. Then there were the green ones — the military men who took us out of the cells — you weren’t allowed to see them at all, they would twist our arms as high as possible and hit us right away if they thought we weren’t bent down low enough.”

Ivan was alone in his cell for a few days. There were two beds in the cell; he was given a sheet and a pillow, but no blanket. There was dried blood on the walls. The toilet and washbasin were in working condition. Ivan was even provided with a toothbrush, some toothpaste, and soap.

Then he was transferred to a cell with Serhiy Kotov and Dmytro Zakharov. Kotov said that he had been constantly tortured in Kherson: beaten, assaulted with a stun gun, and brought before a firing squad.

He was lucky that the cap that was pulled over his face was wrapped very tightly with duct tape, covering his ears — otherwise he could have gone deaf from the gunshots near his head. The tormentors stood on Kotov’s injured leg and beat it.

“He is accused of the same thing I was: he filmed the Russians’ military equipment,” says Ivan. “But nothing was found on Serhiy’s phone. He got ratted out by Mykola Petrovsky, who was arrested in Kherson a week before Kotov was detained. Now they are listed in the same criminal case as accomplices.”

The prosecutor’s visit and singing the anthem

Ivan underwent a polygraph test on 31 August. He said that the interrogation consisted of five blocks of questions. The questions were simple, but there was always one that was sure to make him nervous. They asked, for example, if he could sell his homeland, and for how much, or to whom he passed the data about the Russians’ movements. They said the results would come in four days later, but of course nobody informed Ivan of them.

“When the lawyer my parents hired started filing complaints, the investigator recorded a video in which I said that I was in the pre-trial detention centre voluntarily, that I was fine, like it’s some resort here,” Ivan recalls bitterly. “I couldn’t refuse to record that video, otherwise they would beat me up straight away.”

The next time the investigator came a month later and told Ivan that his parents were continuing to push for his release through a lawyer. He was lucky that his parents did not give up and continued to fight for him for five months. The Ukrainians in the Simferopol pre-detention centre are completely isolated, and no lawyers are allowed to see them. Ivan’s lawyer was not allowed in either, but he was constantly filing complaints. At some point he even managed to get a prosecutor’s inspection launched.

On 22 October 2022, Ivan, Kotov, and Zakharov were transferred to another pre-trial detention facility. Now they were joined by Dmytro Vyadmuk from Kherson. As of today, all except Ivan are still under arrest. On 26 November, Ivan was unexpectedly released, but first the Russians read him a “caution”.

“It was a kind of ‘forgiveness document,’” says Ivan. “It basically says that Russia is very good and I am a scoundrel, but the Russians generously forgive me.”

Ivan was taken to the FSB office in Simferopol and then to the village of Henhorka near the town of Henichesk, where he was held for almost another month. There, the captured Ukrainians were forced to learn the Russian anthem in order to be given food. They learnt it, but never did sing it: one day, a man died in Ivan’s cell. He had been tortured very badly the day before and had a stroke during the night. Ivan is sure that the man’s relatives probably still do not know of his fate. After the incident, the guards temporarily gave up on having the prisoners learn the anthem.

On 21 December, he was unexpectedly called out of his cell, had a cap pulled over his eyes again, and was taken to Henichesk. There, the Russians dropped him off at a bus station and gave him back his passport, which even included 200 rubles (€2) for transportation. It was impossible to get home from Henichesk with that sum of money. The curfew was approaching. Ivan approached various people in the street and asked them to let him use their phone to call his father, but nobody agreed to help. Having nearly lost all hope, he finally met a man who let him use his phone and even wait at his house till Ivan’s father arrived.

“Towards nightfall, my father arrived, and we spent the night together at these kind people’s house. They fed us and treated us very well. The next morning, we drove home. A couple of days later I went abroad.”

‘There is a problem with the Red Cross’

Anastasia Panteleyeva from the Ukrainian Media Initiative for Human Rights explains:

“Our organisation has recorded 948 cases of civilian hostages who were kidnapped by Russian military and security forces. Some of these people (unfortunately, we do not know the numbers) were taken to Russian territory and some are in detention centres on occupied soil. Very few of them have been officially charged with anything or have a court case against them, which would at least mean that Russia officially has some sort of grievance against them. A person can be held for ages in a detention centre, in a penal colony, or even in a basement on occupied soil and still not understand what they are being accused of.

We consider such people to be civilian hostages because they are not POWs. The latter occasionally participate in prisoner exchanges, but civilians do not, because this is nonsense — you cannot make a civilian a prisoner of war.

Ukraine is not going to take Russian civilians as prisoners of war, so there is nothing to exchange our citizens for. Sometimes during swaps Russians give us back civilians, but I don’t understand even how they get into the military’s exchange pool. Maybe it is a problem of perception, and someone thinks that ordinary people are military personnel. Of course, it is good that they are coming home, but it is difficult to understand the logic behind these exchanges.

This problem is constantly being raised both at the state and international level. But no solution has yet been found. There is a problem with the Red Cross, whose volunteers could visit the hostages, but the Russian authorities do not allow them to visit Ukrainian citizens. And no other organisations have the right to visit prisoners. We believe that the representatives of the [International Committee of the] Red Cross could be more persistent. If they give up simply because they are not allowed in, the price of these hostages’ lives will drop immediately, as no one will be interested in their fate.”

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]