South Africa is still trying to decide what to do about the potential arrival of Russian President Vladimir Putin at the BRICS summit, which is due to take place in August. The International Criminal Court (ICC) issued an arrest warrant for Putin, and South Africa signed the Rome Statute, which means it must arrest and deport the Russian leader should he attend the summit. But it clearly has no desire to do so: the South African authorities are going back and forth between offering to grant immunity to Putin and reconsidering their statements. At this point, South Africa has decided to grant immunity to delegations and their heads — but it doesn’t apply to people with arrest warrants looming over them. Irina Tumakova attempts to make sense of this situation with the help of Gleb Bogush, an expert in international law.

Gleb Bogush

international law expert, PhD in law

a postdoc with the University of Copenhagen

South African officials have made various statements about the likelihood of Putin’s arrest. For example, that they have to arrest him if he comes to South Africa.

It’s true. South Africa isn’t just a member of the International Criminal Court — it has signed all of its legal provisions. This includes the provision that ICC warrants must be obeyed in such a situation.

But now they guarantee immunity for members of delegations that come to them. So will they arrest Putin if he goes to South Africa or not?

We don’t know if he even decides to go there. It is unlikely.

And hypothetically?

The South African authorities keep changing their statements. You have to understand that South Africa does have significant elements of democracy, it has a rather vibrant political life, and an independent judiciary. This has to be taken into account when analysing all these political statements. The announcement on Monday, 29 May, was made by South Africa’s main opposition party, and it was widely disseminated.

The statement explicitly called for this arrest warrant to be executed should such a situation arise.

That is, the suspect must be arrested.

What does the statement on immunity mean, then?

An explanation from the authorities has already emerged, saying that the promise of immunity does not apply to the arrest warrant situation. That is, the immunity statement does not apply to President Putin.

The statements change, but the legal status of South Africa doesn’t. They are obliged to execute the warrant. This stems from international law, South African domestic legislation, and the position of South Africa’s Supreme Court.

The South African authorities are unwilling to create a situation that will put them in a difficult spot, and all these statements are partly aimed at creating an impression of uncertainty.

So, they are hinting to Putin that it is better not to visit them?

I suppose there could be an additional message that it’s better not to come. But just in case, they’re preparing an escape manoeuvre, explaining why they will not arrest him. There is supposedly some kind of uncertainty. But there really is none. Part of it, I think, has to do with the internal political processes in South Africa itself.

But when you and I discussed the arrest warrant for Putin last time, you said that heads of state still have immunity. Can a collision arise here: on the one hand, the Head of State’s immunity and, on the other hand, South Africa’s obligations under the Rome Statute?

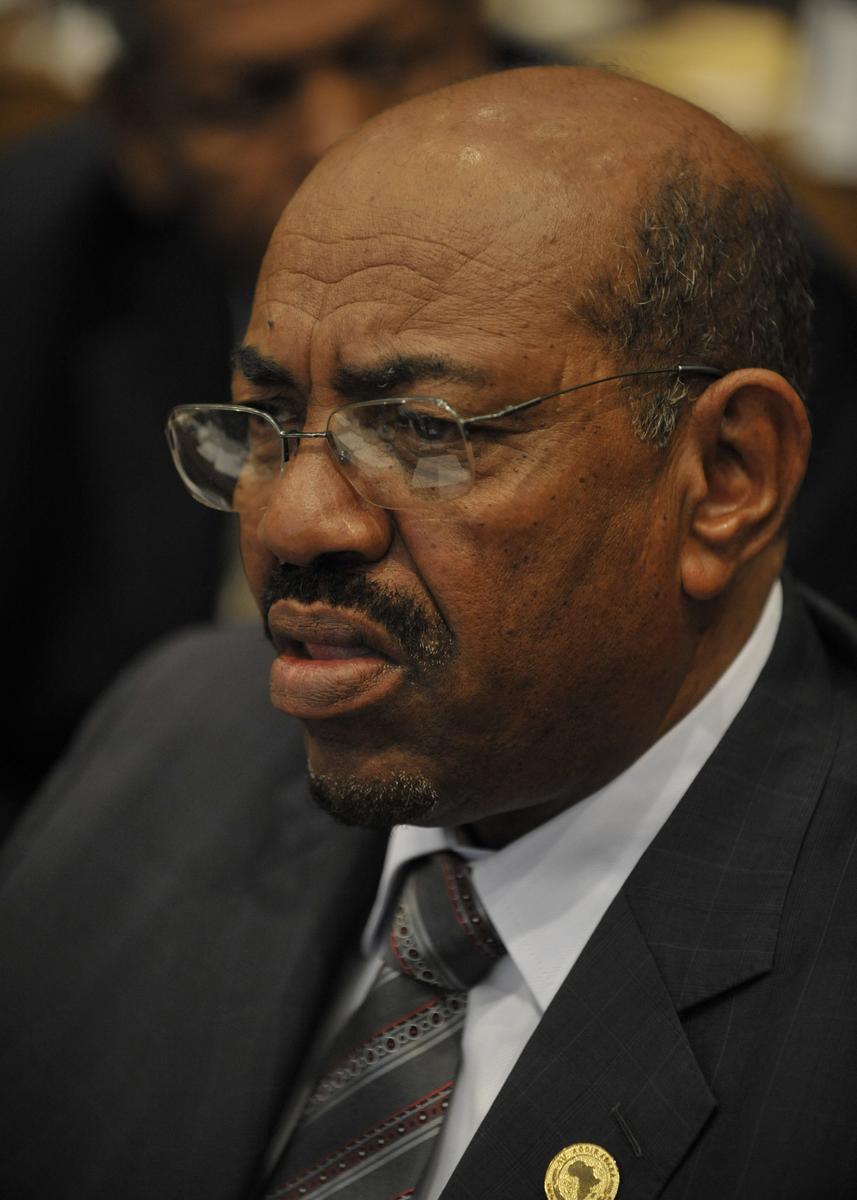

That is a question that will be resolved in accordance with the applicable law. We must remember that South Africa remains a party to the Rome Statute of the ICC. There has been a lot of talk about the country’s withdrawal now, but it is not going anywhere. And it doesn’t plan to, I think. Plus, the position of both the International Criminal Court and the South African Supreme Court was adopted following the situation with Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir.

Omar al-Bashir. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The position is unequivocal. The International Criminal Court also clarified this in a ruling that concerned South Africa. The court spoke in more detail about it when it came to Jordan. Therefore, the situation will be handled in accordance with South African laws.

However, it is difficult to say what will happen in reality. It is clear that if the situation comes down to concrete, practical action, there is minimal scope to force specific representatives of the state, its police forces, or the president of the country, to make any decisions. So it seems that every effort will be made to avoid this situation. I fear South Africa is no longer that glad to be hosting the summit.

Is there any third party that could come to South Africa and arrest President Putin there?

Some West Cape provincial leaders have already said: if the government fails to act, the West Cape police force will execute the warrant in accordance with the provisions of the Rome Statute. I would take this with a grain of salt, but it shows the domestic political friction this issue is causing in South Africa.

Russia’s prevalent attitude is that the rule of law is separate from the country’s authorities. This is far from being a universal case.

I would not underestimate the importance of democratic institutions in South Africa.

To put it bluntly, this is not a good state for President Putin to visit in this situation. Although states often violate international law.

BRICS leaders in 2014. Photo: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0

I do not recall a time when the state explicitly emphasised that immunity is guaranteed to visitors before any summit. Why do they need this statement anyway?

I do not rule out that these are just standard rules of procedure. We have not kept track of such things until now. But in this case, the South African authorities are referring to international conventions, and the head of state’s immunity is provided for by ordinary law. And don’t forget that there are also other members of delegations. The move could be seen as an attempt to create a safety net.

The statement on immunity refers to ministers, in particular foreign ministers. Putin is not, after all, a minister.

Putin, of course, is not a minister. But he is a member of the delegation. There is a certain cunning here: as if the statement refers to one person, and not another. But we must understand that we are talking about an international meeting, and all delegations here are state delegations. Nothing would have changed without this statement; it only confirmed what already exists. I wouldn’t overestimate it because, again, nowhere does it say that the ICC warrants will not be honoured.

The bottom line is this: South Africa is well aware of the situation it finds itself in. I would consider all their statements from this point of view: they want to avoid this situation and its international repercussions. South Africa also had a period when it was in isolation, under sanctions, and so on. And now, it wants to avoid creating an unfavourable image of itself, especially since not everything runs so smoothly there.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]