Almost every single day of the Ukraine war has been a battle between Russian missile launching crews and Ukrainian air defence troops. According to Kyiv and experts, the Ukrainian army downs an overwhelming majority of the missiles and drones launched by Russia. Meanwhile, Russia cannot boast the same efficiency. The recent Kremlin dome explosion and other successful attacks on military and infrastructure facilities prove this. Novaya-Europe investigates what weapons and air defence systems Russia and Ukraine have and how efficiently they are used now.

Reaching Moscow

Ukraine can reach many targets, including those located in Russia, with two types of weapons: missiles and drones.

“The UJ-22 Airborne drones produced in Ukraine today are of the aircraft type with an internal combustion engine and can return from a distance of up to 700 km or be used as a kamikaze drone at a distance of up to 1,500 km,” Roman Svitan, a flight instructor and Ukrainian reserve colonel, told Novaya-Europe. “Dozens of such drones have already flown unimpeded into Russia and even into the Moscow region. This drone can carry 20-25 kg of ammunition: several grenade launcher rounds, mortar shells, or properly packed explosives. Fuel depots, warehouses and lightly fortified targets can be attacked with such devices.”

Moreover, Svitan believes that the Ukrainian army has dozens of various models with similar tactical and technical features provided by Kyiv’s allies in the West.

Discussing the Ukrainian-made UJ-22 Airborne drones, Israeli military expert David Sharp notes that at the moment it’s not evident that Kyiv possesses a large number of such devices. Those that have been used have not always reached their targets, often falling far from any military facilities. However, even this aircraft can operate successfully and benefit Ukraine. As the Russian-Ukrainian conflict experience has shown, mass-producing modern drones is not an easy task. It’s not surprising that Russia has not managed to do this either, even though the Lancet loitering munition has become a serious threat to Ukrainian forces. Up to 200 hits by this drone on Ukrainian military hardware and equipment have been recorded.

Roman Svitan recalls the Soviet-era Tu-141 Strizh — a multipurpose tactical UAV, a few of which are still used by the Ukrainian army. Svitan refers to this drone as proper unmanned aircraft. This five-tonne drone can travel about 1,000 km at a speed of over 1,000 km/h and carry several hundred-kilogram aviation bombs FAB on board.

Ukraine’s UJ-22 Airborne drones

The Soviet Tu-141 Strizh drones, in David Sharp’s view, are also a very formidable weapon. The Israeli expert recalls two Strizh attacks on the military airfield in Russia’s Engels as turning-point incidents. At the same time, David Sharp surmises that Ukraine is not able to produce new units of such weapons and a small number of units left in the depots from the Soviet times is used for air raids.

Both Strizh and other Ukrainian drones could in theory reach Moscow and other major Russian cities.

David Sharp also notes that London has promised to provide Kyiv with hundreds of kamikaze drones with an attack range of 200 km. Interestingly, there are no such devices in UK depots. It is possible that the drones are specially manufactured for exports to Ukraine. The tactical and technical features of these drones are currently unknown. However, if this type of weapon proves to be effective, it will cause significant problems for Russia.

Airborne lend-lease

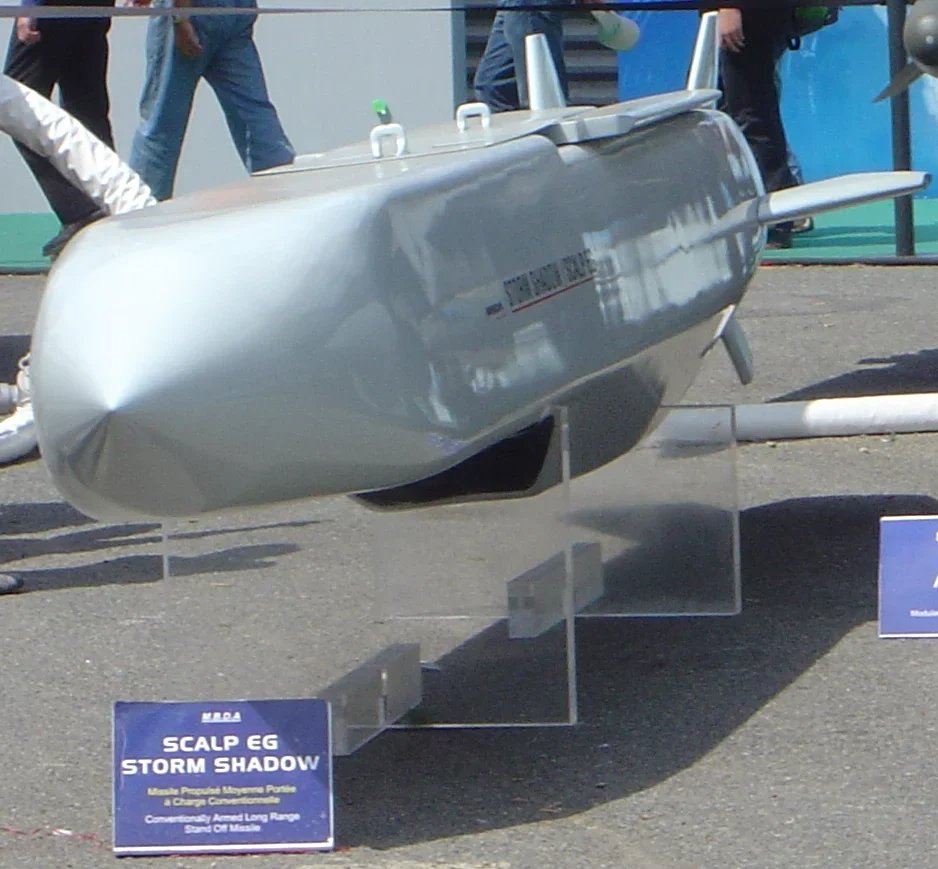

The news emerged earlier that Ukraine would receive Storm Shadow, an Anglo-French missile known in France as SCALP. Their operational range is at least 250 km (other sources state it as 300 km). When fired from a jet flying next to the frontline, for example, these projectiles can strike targets in all occupied territories of Ukraine, including Crimea and Sevastopol.

The Crimean Bridge can also potentially be targeted. Svitan is convinced that this vital artery will be destroyed right in the beginning of the large-scale Ukrainian counteroffensive.

“The French will potentially export a SCALP modification with a range of 560 km,” Svitan notes. “These missiles have a turbojet engine and their range is directly related to the amount of fuel they carry. It is a very powerful missile, with a warhead weighing 500 km. They are accompanied by armaments which become known only after they have been used. For example, the ADM-160 electronic warfare missiles hit Luhansk along with Storm Shadow. Nothing was openly reported about these lend-lease supplies.”

Storm Shadow missile. Photo: Wikimedia

According to David Sharp, it is worth mentioning that ADM-160 projectiles are used with jamming devices. This weapon is used to confuse Russia’s air-defence systems and get in the way of downing missiles coming towards it. It is unclear what was specifically targeted in Luhansk when Storm Shadow was used. The Ukrainian army was possibly trying to strike Russian personnel quarters. There’s currently no information about this operation available.

“I still don’t have full confidence in how the Storm Shadow missile is launched,” says the Israeli military expert. “Most likely, they’ve managed to adapt Soviet Su-24 frontline bombers for this purpose. However, it can also be sea-based launching. A modification capable of being launched from a ship wouldn’t be difficult to repurpose for ground-based operations. The range of this missile, as declared by the UK, is over 250 km. I suppose we’re talking about the standard export version, capable of hitting targets at a distance of 290 km. After all, international conventions prohibit the sale of high-powered missiles with an attack distance of more than 300 km. However, there’s no clear understanding of this issue yet. Agreements may not be taken into account in situations of extreme necessity.”

The number of missiles provided by the UK and France is unknown at this point. David Sharp assumes that it can’t be too high. Judging by open sources, London itself only has a few hundred of these missiles in its arsenal. The price of a single missile exceeds $1 million.

However, it’s possible that 10-20 missiles will be supplied each month. It’s crucial to carefully designate targets for this one-of-a-kind weapon.

According to David Sharp, both types of the cruise missile, British and French, can travel towards their targets via a very sophisticated trajectory and approach the target for the final strike from a side that the enemy does not expect. While en route, they circumnavigate enemy air defence deployment areas. SCALP and Storm Shadow are made of materials that radars cannot easily pick up and travel at very low altitudes and a very high speed, bypassing any obstacles, which presents a very complicated target for air defence efforts. In comparison, the ATACMS ballistic missile with a range of up to 300 km that Kyiv has been expecting for a while seems to be an easier target to intercept.

ATACMS Army Tactical Missile System. Photo: EPA-EFE / YONHAP SOUTH KOREA OUT

Moreover, Ukraine now already has JDAM kits for building guided gliding munitions based on Soviet free-fall aerial bombs. Their range stands at 40-75 km. Another comparatively long-range weapon received from Kyiv’s Western allies is the GLSDB bombs launched at 150 km by HIMARS or MLRS M270.

“We will definitely get something if not ATACMS,” Roman Svitan is certain. “The UK is armed with the Turkish KHAN missile, there are several hundreds of them in their depots. They can give us this type of ballistic missile with a range of 250-300 km and a 500-kg warhead.”

Rules of the game

Many tempting targets are within range of Storm Shadow and SCALP missiles in Russia as well. This projectile can easily reach Belgorod, Kursk, Bryansk, and Rostov-on-Don. Many military facilities and airfields are located near these cities. David Sharp argues that the ban on Western weapon attacks on Russia within its internationally-recognised borders is in place and being respected but for a few exceptions. Otherwise, what stops Ukraine from trying to destroy, for example, an airfield with planes on the tarmac?

“Americans directly prohibited these attacks,” the Israeli expert says. “Pentagon sources reported this. HIMARS, for instance, were never used to attack Russian soil.”

The only lend-leased weapon that has been proven to cross the Russian border is HARM anti-radar missiles that were found in the Belgorod region.

“It would be very irrational for Kyiv to break this promise,” Sharp tells Novaya-Europe. “Because the arms flow can be cut off then.”

Svitan, meanwhile, is certain that this condition not to attack Russia proper with supplied weapons allegedly imposed by the West is nothing but a journalistic invention.

“No one made any promises,” he claims. “Ukraine is sovereign in deciding what to fight and with what arms. If a target worth of being used by Storm Shadow or any other expensive projectile emerges in Rostov-on-Don or Belgorod, the Ukrainian army will be able to strike it.”

Impact zones of Ukrainian and Russian weapons

Shield is better than Kinzhal

Roman Svitan expects Ukraine to receive additional air defence systems and ammo for them in the near future. He says that three Patriot systems with eight batteries each are required in order to cover all of Ukraine. Their range in the PAC-2 modification is up to 150 kilometres. The density of weapon deployment is currently not sufficient to completely secure all Ukrainian cities. The Ukrainian capital is well protected by various air defence systems. Almost all weapons, from hypersonic missiles to Iran’s Shahed drones, are downed over it. But about 70% of Ukraine’s territory is exposed to air strikes now.

At the same time, the Ukrainian army has learned during the war how to repel Russian mass-scale attacks and to intercept virtually every type of missile and drone flying towards Ukrainian cities. Certainly, the results shown by the air defence forces over the Kyiv area are more than successful. An overwhelming number of targets are shot down there. But quite a few Russian drones and missiles still reach the capital.

Which means that they cannot be intercepted from afar. And that, in turn, means that other parts of Ukraine are exposed to Russian attacks.

To fully secure its territory from Russian weapons, Ukraine needs to establish a contiguous radar field over the entire country, install a larger number of anti-aircraft systems, and integrate all of this into a unified structure. Kyiv hasn’t yet received all the necessary equipment to achieve this. As of today, Kyiv is known to have two Patriot batteries and one SAMP-T. The exact number of missile launchers isn’t disclosed, but according to some sources there may be about 20 of them in total. Only these systems are capable of intercepting Russian missiles like Kinzhal or Iskander. However, anti-aircraft missile systems themselves need to be very close to the target being attacked by the enemy. Patriot PAC-3 missiles can shoot down a hypersonic missile within a few dozen kilometres, roughly within a radius of 20 km. On the other hand, with the PAC-2 variant, jets can be targeted at a distance of over 100 km.

Patriot, US surface-to-air missile system. Photo: EPA-EFE / Pawel Supernak POLAND OUT

Russia recently attempted to destroy a Patriot surface-to-air missile system with a combination of missiles and rockets. However, latest reports suggest that it was only able to cause minor damage without rendering the system inoperable. At a Pentagon briefing, Defence Department spokeswoman Sabrina Singh said that the damaged system had already been repaired and put to use. So far, the US system is winning in this death match.

The main issue facing the Ukrainian air defence efforts is the lack of precise information about some low-altitude travelling attack machines.

Reconnaissance jets of allies do not fly into Ukraine and do not see everything while on missions over Poland and Romania.

Moreover, Ukrainian troops are forced to learn how to operate Western systems right in the midst of the fighting.

According to BBC News Russian correspondent Pavel Aksenov, Ukraine is also receiving support from Western partners in this regard. Airborne radar (long-range radar detection) reconnaissance aircraft see at a distance of about 400 km and are likely to have information about sea launches of Kalibr missiles or the takeoff of Mig-31Ks carrying Kinzhals. Russia’s active air defence and electronic warfare radars can detect such aircraft at even longer ranges. The allies are sure to relay this information to Kyiv, helping them prepare to repel air strikes. In addition, Ukraine has been supplied with many radar systems to track attacking targets.

Mig-31K with a Kinzhal hypersonic missile dummy. Photo: Wikimedia

“During the war, the Ukrainians have learned to calculate possible courses of Russian missiles and drones, which helps air defence systems to fight them more and more effectively,” Pavel Aksenov explains. “In addition to military air defence, Ukraine also has civilian air defence. Citizens actively report sightings of missiles or drones in a special app called ePVO, which in the case of slow-flying drones also probably helps air defence systems go live to repel strikes.”

It is not clear how many different types of missiles Russia has left today. On the other hand, Kinzhals have rarely been used, and their stockpile could be quite large. David Sharp is confident that the Russian military could produce several dozen cruise missiles a month.

“Russia has stopped hitting Ukraine with heaps of 70-80 missiles at a time,” the Israeli expert says. “However, in the run-up to the Ukrainian counteroffensive, we see attempts to disrupt Kyiv’s plans with shelling attacks. But the choice of targets for Russian attacks raises big questions. Targets that often clearly have no military significance are struck. Remember the shelling of shops containing spent rocket fuel and decommissioned engines in Pavlohrad or the depot of long-expired Soviet bombs ready for disposal in Khmelnytsky.”

Sky full of holes

When it comes to the effectiveness of Russian air defences, according to David Sharp, the vastness of Russia’s territory must be taken into account. It is impossible to cover the sky over the entire country of this size. Even securing all major cities and military facilities is extremely difficult. There is an additional problem with intercepting drones. Small drones flying slowly at low altitudes represent a difficult target for classic air defence systems.

“When the whole Russian army did not show itself to be a great force, to put it mildly, why should we believe that air defences are fully ready and loaded?”

David Sharp poses the question. “Russian air defence issues have come to the forefront quite a few times. Drones conducted successful operations in many Russian regions. The consecutive strikes on an airfield in Engels is a shameful stain for the Russian army. Meanwhile, Russian anti-aircraft units downed their own planes on a few occasions.”

David Sharp is convinced that although Russia prides itself on its air defence, it turns out that the systems developed in Russia lag behind the high Western standards in terms of technology. There is no such thing as a completely airtight air defence, but Russia’s performance clearly falls below expectations. As Ukraine develops new types of weapons capable of destroying targets deep within enemy territory, the Russian air defence system faces an additional test of effectiveness.

“Russia has two different options for air defence. The army has a military air defence system, and separately there are air defence forces that are part of the aerospace forces,” Pavel Aksenov says. “The air defence forces, which are part of the air force under the command of Sergei Surovikin, are involved in the protection of big cities and important strategic facilities. In February, it was reported that the military air defence systems might be transferred under the jurisdiction of the air force. This information was never officially confirmed, only reported by the TASS news agency, citing its sources.”

If this turned out to be true, according to Pavel Aksenov, it could be dictated by a desire to resolve some of the air defence organisation problems by transferring it to a “specialised” command. On the other hand, some commentators noted that such a transfer would complicate lives of ground units commanders, who would have to coordinate the actions of air defence units assigned to them with the other armed force structures, which would hinder operational tasks as it would increase the number of links in the chain of command.

In Russia, as many experts point out, there is a problem with the effectiveness of the chain of command today. According to Aksenov, the operational response to emerging threats is complicated by the fact that information goes through several instances “upwards” so that when a superior commander has made a decision, his order is then passed down again to those who are supposed to implement it.

According to Pavel Aksenov, both the Ukrainian and Russian air defence systems operated under more or less the same principle, because the two were based on the Soviet system and used weapons developed by the Soviet Union, like in Ukraine, or built in the same technological spirit, like in Russia.

At the same time, Moscow has been allocating huge funds to improve its air defence troops, achieving relatively big success in this endeavour.

“However, the very principle of echelon air defence as well as several tactical moves allowed Ukraine, being a country armed with outdated and sparse systems, to force Russian aviation to stay away from its rear defence lines,” Aksenov continues. “Moreover, the Russian air force and its command’s general lack of readiness to conduct air operations also came to the forefront.”

However, Aksenov notes that because Russia’s air defence, just like any other, is incapable of covering the whole vast Russian territory, certain “windows” of opportunity inevitably emerge which became clear after Ukrainian drones managed to fly deep into Russia. Russian anti-aircraft units can boast about successfully intercepting HIMARS, MLRS, and other Western weapons but after Kyiv received longer-range British and French cruise missiles, the scale of territories which will have to be protected against any potential Ukrainian attacks will increase significantly. If the air defence in these areas is not boosted by adding more systems, the air-defence coverage drops significantly.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]