In 2002, Russia’s new president Vladimir Putin visited Poland and met his counterpart Aleksander Kwaśniewski, handing over declassified documents of the WW2 era that touched upon Władysław Sikorski, the leader of Poland’s government in exile, into Poland’s possession. The intention of the gesture was to stress that after long years of tense relations, the sides are eager for reconciliation and partnership, namely when it comes to interpretation of some of the most problematic issues of mutual history.

It looks like there is nothing left of this intention in 2023. Among the recent confrontations covered in the media was the incident with Russia’s ambassador to Poland: he was refused entry to the burial site of Soviet soldiers in Warsaw where he was going to lay flowers on 9 May. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Warsaw and Moscow have teetered on the precipice of cutting off diplomatic relations altogether. No thaw is to be expected as people in both countries consider each other enemies.

Novaya-Europe has reviewed what ups and downs happened in the Russo-Polish relations during the past 25 years, trying to find out if Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the invasion of Ukraine is the only stumbling point.

Russia’s ambassador to Poland, Sergey Andreev, tried to lay flowers at the Memorial to Soviet Soldiers in Warsaw on 9 May 2023. However, he failed to do this. Ukrainian and Polish activists who were protesting against Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in this location blocked the way for him. The police were present, but did not intervene.

Sergey Andreev approaching the Memorial to Soviet Soldiers in Warsaw. Photo: screenshot from the video

A bit earlier, in late April, the Polish authorities confiscated the building that housed a school for the children of Russian diplomats in Warsaw. At the same time, Poland’s Foreign Ministry stated that this had been done by court decision and did not violate the local laws: it was the Polish state that formally owned the building. However, Russia’s Foreign Ministry considered Warsaw’s step a violation of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations and invasion of Russia’s diplomatic property. Russia warned there would be “consequences for the Polish authorities and Poland’s interests in Russia”. The Russian Investigative Committee promised to launch an investigation into this matter.

After Russia invaded Ukraine last year, the entire relationship between Moscow and Warsaw has been an exchange of hostile rhetoric. Last spring, a month after the start of the invasion, each country expelled 45 diplomats. Last autumn, Poland’s authorities banned Russian nationals with tourist Schengen visas from entering the country and announced their plans to erect a wall on the border with Russia’s Kaliningrad exclave. In December 2022, the Polish parliament adopted a resolution that referred to Russia as “a state supporting terrorism”.

It looks like the relations between the two countries are at the lowest point in modern history.

But it has not always been this way: despite numerous contradictions and historical grievances, Moscow and Warsaw had been trying to maintain normal dialogue for the best part of the post-Soviet period.

Overcoming the past

Moscow and Warsaw have few historical reasons to like each other. The history of their relationship is full of invasive wars and periods of occupation, so times of occasional peaceful coexistence seem more like exceptions.

There were several military and political confrontations between Poland and Soviet Russia in the 20th century alone. A Soviet-Polish war started in 1919: Moscow was trying to Sovietise the Western parts of the former Russian Empire, while the young Polish state was eager to take control over the lands that historically had been part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. The war ended in 1921 in a victory for Warsaw.

In 1939, Poland was occupied by the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, and in 1940 the notorious Katyn tragedy happened when over 20 thousand Polish nationals were executed in Soviet labour camps. The USSR only assumed its responsibility for the massacre in 1990. A pro-Soviet regime was installed in Poland after WW2, and the country had been under Moscow’s influence up until the late 1980s when the first free election was held there.

Despite the heavy historical burden, Moscow and Warsaw were trying to build a partnership in the 2000s, and even achieved certain success, although these attempts were often bogged down by political controversy.

Polish President Aleksander Kwaśniewski hosts an official dinner during Putin’s visit to Poland. Photo: Kremlin

In 2002, the presidents of the two young democratic countries, Vladimir Putin and Aleksander Kwaśniewski, exchanged formal visits. Putin’s trip to Warsaw in January 2002 was the first visit a Russian president paid to Poland since 1993. It was then when Putin called the 1990s “a time of missed opportunities” for the mutual relationship that had by then, as Putin said, reached “a new positive level”. This assessment was not far from being true.

During his visit, the Russian president handed over declassified copies of documents on Władysław Sikorski, the leader of the Polish government in exile during WW2, to Kwaśniewski. He also promised to pay compensation to Polish nationals who had suffered from Stalin’s oppression. The visit resulted in the creation of a Poland-Russia Group on Difficult Matters with a goal to discuss problematic issues in the relationship between the two countries, the historical controversy being its priority.

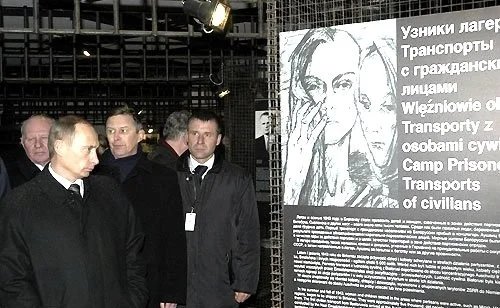

Vladimir Putin visits a museum exposition in Auschwitz. Photo: Kremlin

Mutual visits and meetings continued after Putin’s landmark trip. However, the relationship saw a deterioration after the winter of 2004-05 because of the Orange Revolution in Ukraine.

In that year, after the second round of the presidential election, the victory was awarded to the Russia-backed candidate Viktor Yanukovych. The official election result contradicted the exit poll data and the interests of a significant part of Ukrainian society that supported Viktor Yushchenko, a pro-Western candidate. This provoked mass protests in the country as people demanded the second round of the election to be held again.

The Polish side and Kwaśniewski himself took part in settling the conflict. It was the Polish president’s initiative to set up a roundtable discussion of the controversy. On top of that, when the public pressure resulted in repeat voting and Yushchenko won the election, the Polish members of the European Parliament were among the movers of the resolution that recognised the vote as legitimate.

The rift in the relationship turned out to be so painful that the two sides exchanged statements that were closer to today’s rhetoric than that of the mid-2000s in terms of tension.

“The Polish speak of Russians the same way antisemites speak of Jews,”

Gleb Pavlovsky, who was Vladimir Putin’s advisor at the time, said during his visit to Warsaw in the summer of 2005. “You are looking for an enemy and you’re finding it in Poland,” Adam Rotfeld, the Polish Foreign Minister, responded to that.

A freeze in the relationship was sealed in 2005 when the right-wing Law and Justice party, led by the Kaczyński brothers who positioned themselves against rapprochement with Russia, came to power in the country. The leaders of the party stated on multiple occasions that their foreign policy priority was protecting national interests, while Russia was considered one of the biggest threats.

Support independent journalism

‘Georgia today, Ukraine tomorrow’

A new attempt to find common ground and “unfreeze” the relationship became possible after a liberal government led by Donald Tusk came into power in Poland in 2007 and Dmitry Medvedev became the president of Russia in 2008.

Vladimir Putin, who was Russia’s PM back then, even published an open letter to the Polish nation in the Wyborcza newspaper. In his address, Putin condemned the Molotov—Ribbentrop pact, the one that virtually predestined the partition of Poland between the Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in 1939. Putin also visited Gdańsk as part of the policy aimed at “smoothening historical contradictions”, arranging his visit to the date of the 70th WW2 anniversary.

However, the attempts to draw historical disputes aside in favour of partnership could not stave off new confrontations in the political and economic relations between the countries. The reason was the construction of Nord Stream, a gas pipeline that could potentially connect Russia to Western Europe via the bottom of the Baltic Sea, bypassing Poland and the Baltic states. The Polish authorities were of the opinion that the pipeline was crucially undermining the country’s energy security: in case of any new altercation, Russia would continue selling natural gas to Europe while completely cutting Poland off from gas supply.

Apart from that, Poland openly supported Georgia in the Russo-Georgian conflict. In August 2008, Polish President Lech Kaczyński arrived in Tbilisi alongside leaders of other Eastern European countries where he delivered the following speech: “Georgia today, Ukraine tomorrow, the Baltic states the day after tomorrow, and the next in the line will be my country, Poland.” During Kaczyński’s next visit to Georgia in November 2008, his presidential motorcade that also had Georgian president Mikhail Saakashvili in one of the vehicles was shot at not far from the border with the South Ossetia region. Although neither side claimed responsibility for the incident, Kaczyński blamed it on Russia’s military.

Vladimir Putin and Dmitry Medvedev light candles in a chapel on the territory of the presidential residence to honour those killed in the Smolensk plane crash. Photo: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0

The Smolensk disaster

The incident that largely preordained further negative attitude of a significant portion of Poland’s elite towards Russia was the crash of the Polish presidential jet near Russia’s Smolensk in 2010. In April that year, Poland’s delegation was on its way to a tribute ceremony timed to 70th anniversary of the Katyn disaster. The crash killed all 96 people onboard, including President Lech Kaczyński and his First Lady, the chairman of the National Bank, the entire Polish military top brass, several MPs, and other officials.

The Russian investigation concluded the following in January 2011: the reason behind the crash was the pilots’ refusal to land the jet on a reserve airfield, despite the poor weather conditions they were aware of. As an additional factor, Russian experts noted that the chief commander of the Polish Air Force was inside the cockpit during the flight, “putting mental pressure upon the pilots”. During the investigation, alcohol was found in the chief commander’s blood.

The Polish side completed its own investigation, patronaged by Tusk’s government. This investigation did not contradict the Russian one, but stressed some of the details in a different way. In particular, it mentioned the lack of necessary instructions from the Russian air traffic control, poor training of the Polish pilots, and the fact that the Smolensk North Airport was non-compliant with safety requirements. That said, the report also stressed that “unauthorised individuals were coming inside the cockpit”, interfering with the pilots’ work.

An impromptu memorial in Smolensk near the crash site. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

However, Jarosław Kaczyński, the brother of the deceased president, harshly criticised both investigations. “Tusk did nothing to put Poland in charge of the investigation. He was unable to advocate the interests and the honour of Poland on the global arena,” he stated after the report had been published, noting that he would do anything to arrange a proper investigation. “It is our duty before the deceased and before the Polish people.”

Russia’s refusal to hand over all of the plane’s debris to the Polish side caused more suspicion. In 2015, Russia’s irreplaceable ambassador to Poland Sergey Andreev stated that laws did not allow Russia to return the debris before the investigation was completed by the Polish side. Andreev also expressed confusion since Poland had not finished the investigation despite having been presented final reports. Russia’s Foreign Ministry published an identical statement in 2021.

Apparently, this tragedy became the turning point of Jarosław Kaczyński’s attitude towards Russia and his political opponents inside Poland. After his Law and Justice party came to power in 2015, a new investigation was launched, led by Antoni Macierewicz, the Defence Minister and member of Kaczyński’s party.

In 2022, after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Polish investigation concluded that the plane had crashed after an explosive device detonated onboard.

Macierewicz’s commission stated that the explosion had been plotted by Russia, and that Polish pilots made no mistakes. Jarosław Kaczyński then accused Tusk’s government of suppression of evidence. The Russian side denied the allegations.

However, in September 2022, a journalistic investigation by Polish TV channel TVN24 found out that Macierewicz’s commission had concealed the facts that contradicted the wilful blowing up theory. The facts in question were, among other things, the conclusions made by American experts from the National Institute for Aviation Research who did an expert study upon a request of Macierewicz’s commission. A computer-generated simulation run by the Institute’s experts confirmed that the damage suffered by the jet could have been inflicted by a collision with trees, and not by an onboard explosion. It was then when the opposition in the Polish parliament stated that the Law and Justice party triggered a “political war using lies and manipulations”.

As a result, the Smolensk disaster not only largely determined the Law and Justice party’s attitude towards Russia, but also became subject to political confrontation inside Poland.

No more momentum

However, Moscow and Warsaw managed to hold on to the momentum of previous cooperation: the sides kept working together on some issues while clashing over some other ones. In late 2010, Dmitry Medvedev visited Poland where he met Donald Tusk and Bronisław Komorowski, the new president. Medvedev assured the Polish side that an impartial investigation would be conducted on the account of the Smolensk tragedy. The leaders of the two countries once again confirmed their commitment to partnership and desire to develop economic, energy and humanitarian cooperation.

In 2012, Patriarch Kirill of Moscow paid a historic visit to Poland where he held a meeting with Józef Michalik, the leader of Poland’s Catholic Church. The two religious leaders signed a joint message to the peoples of Russia and Poland in which they called on the “fraternal peoples” to reconcile, and all believers to “ask forgiveness for mutual hard feelings, for injustice and evil.”

This, however, could not prevent the relationship between the two countries from descending into enmity after Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014. Poland was one of the first countries to condemn the annexation. Warsaw supported the new Ukrainian government and began to actively seek tougher sanctions against Russia. When Law and Justice came to power in the country again in 2015, the geopolitical clash became the new reality, and the multi-vector approach, same as partnership, had to be ultimately abandoned.

Poland’s foreign policy strategy, adopted in 2017, referred to Russia as the number one culprit for the change of the European security order. Poland started to build up its military potential, diversify energy supplies, and strengthen cooperation with NATO.

Mateusz Morawiecki. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

At the same time, Poland began to openly criticise those of its European partners that opted for a more composed attitude towards Putin’s regime after the annexation of Crimea. The main target for Poland’s criticism was Germany that continued its joint Nord Stream gas pipeline project together with Russia. Mateusz Morawiecki, Poland’s PM, called on Germany to withdraw from the project in 2020 after Russian opposition leader Alexey Navalny had been poisoned.

The Russian leadership finally abandoned its attempts to smooth out historical contradictions: Putin now justifies the Molotov—Ribbentrop Pact, comparing the role of the USSR and Germany in WW2 is considered an offence in Russia, commemorative plaques in the memory of the executed Poles are being destroyed in the country, and the recognition of mutual claims and special commissions on the settlement of the relationship are now out of the question.

The relationship between Moscow and Warsaw had apparently reached its lowest point in modern history by the early 2020s. The full-scale invasion of Ukraine triggered a new escalation.

No chance

Poland became one of Ukraine’s main European allies in 2022. The country welcomed most refugees, namely over 1 million people, and was one of the top suppliers of Western munitions for Ukraine’s military. Moreover, Poland continues to initiate European sanctions against Russia: the Polish government suggested in early May that the EU’s 11th sanctions package include restrictions for Russia’s agriculture.

Unlike many other European countries, the Polish society is united when it comes to supporting Ukraine. In all of the EU, the average proportion of survey respondents ready to support further arms supplies for Ukraine stands at 56%, while this figure is as high as 89% in Poland. This support does not decline: figures recorded in the summer of 2022 stood at 84% of the Polish population.

Russia has Poland, just like other EU nations, on its list of “unfriendly countries”. In addition, Moscow does not hesitate to use Poland for its domestic propaganda purposes: claims about Warsaw’s desire to seize a part of Ukraine often appear in pro-state Russian media.

Finally, public opinion surveys confirm that the two peoples share the same hostile attitude towards each other. In 2022, 94% of Poles considered Russia to be Poland’s main threat, and 91% of respondents had a negative attitude towards Russia, compared to less than 70% a few years back. In Russia, 41% of respondents included Poland into the top 5 list of “unfriendly countries” after the US and the UK. This figure doubled compared to 2021 results.

Under these conditions, the possibility of a thaw in relations is completely out of the question; stable public opinion figures in both countries make such political decisions extremely unlikely.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]