When the whole country took to the streets

When Alaksiej Velikaselec was beaten up by riot police units in downtown Minsk in July 2020, he thought it was a necessary sacrifice: freedom does not just fall from a tree, you need to fight for it, and your opponent in this fight knows no mercy.

When a video showing a man being dragged into a police van and Alaksiej trying to wrestle him out of the police hands was uploaded to Onliner, a popular Belarusian portal, the protagonist of this story did not think that it was dangerous: it seemed like these videos would soon end up in archives and journalists would put them together from time to time to celebrate another anniversary of the victory over the dictatorship.

When Alaksiej left Belarus in autumn 2022, he did not mean to stay in Europe for long. But that’s not what happened in reality.

Alaksiej had been protesting from 2010 and onwards. However, he did not think that the protest would change anything: he only came out to raise the protester numbers and show that a lot of people oppose the authorities. He did it to live at peace with his conscience and know that he did not sit back and remain silent.

But when the presidential elections were announced in the spring of 2020, he decided that it was not enough to just protest. Alaksiej joined a public action group of opposition figure Viktar Babaryka and signed himself up as a volunteer for all civil rights projects — from independent monitoring to CCTV tracking. He printed out leaflets of independent candidates and disseminated them around his area, registered as an election observer, and took part in rally bike rides. It all seemed like a normal political process at first.

Later, opposition activist Syarhiej Tsikhanousky and Viktar Babaryka, who both intended to run for president, were arrested, another would-be presidential candidate Valery Tsapkala was denied registration, and people took to the streets in protest.

Alaksiej saw a guy being dragged to a police van in downtown Minsk. People were still unaware of what could happen and Velikaselec ran towards a special police force officer to try and wrestle the guy out of his grip. A stranger approached them as well. They helped the guy to free himself and he managed to run away. Alaksiej was battered but still felt like a victor who prevented an injustice.

Then it was 9 August when it seemed like the whole country came out to protest — even in cities where Lenin statues still adorn central squares and no rallies ever took place. People were coming out every day despite bruises, rubber bullets, stun grenades and water guns. Syarhiej Tsikhanousky’s birthday was on 18 August. Babaryka camp volunteers asked Alaksiej to come to the detention centre where the politician was held and film the rally. He did just that. Meanwhile, security officers dressed in civilian clothes were recording him and, naturally, all the others who came out to protest near the detention facility that evening. Alaksiej did not think about any danger then. He took to the square every evening.

The rest will get the same

In late October 2020, Alaksiej’s kids had autumn school holidays, while his wife contracted COVID. She asked him to take the children away because staying in a tiny apartment was not a great idea. Alaksiej and the kids got in a car and travelled to Switzerland via Poland that opened its borders to Belarusians despite the pandemic lockdown. Alaksiej’s mother and sister have been living in Switzerland since the 1990s and have Swiss citizenship. The whole family would go to see his mother regularly. Alaksiej even started a small business thanks to these trips. He first transported cars from there and then began supplying sports equipment from there to Belarus.

So he saw his mother. There were lots of hugs. They dreamt together about a new Belarus that was just within reach. Meanwhile, the Belarusian authorities started cracking down on the mass protests by placing people in detention centres, and not just for 24 hours. A real bloodbath took place in Minsk’s Arlouskaja Street on 25 October. Artist Alyaksandar Nurdzinaw was arrested on October 26 for taking part in the 9 August rally (he got four years in prison). Drummer Alaksiej Sanchuk was detained on 4 November: photos from protest rallies were found on his phone and he was ultimately sentenced to six years behind bars. Viktoryia Kulsha and Aleh Krautsou were taken into custody at the same time (both in prison, Viktoryia recently got an additional year of imprisonment).

Mikalai Karpiankou, head of the Belarusian Interior Ministry’s Chief Organised Crime and Corruption Fighting Directorate at the time (now deputy interior minister), said in early November that 500 protesters had already been detained while the rest would get the same. He also said that law enforcement agents would use weapons against the protesters “in a humane way, including firearms”.

The horrific murder of Raman Bandarenka took place on 11 November right in the backyard where locals were hanging red-and-white ribbons and having tea.

Journalist Katsiaryna Barysevich and doctor Artsiom Sarokin were arrested later — Katsiaryna published the doctor’s verdict that deceased Raman Bandarenka was battered to death and not drunk as propagandists tried to make it out to be. It was dangerous to come back. Later, Karpiankou and other law enforcement and security officials rolled out threats via state media that each person who took part in protests would be found and get what they deserve. That’s when Alaksiej decided to seek protection.

Overt bluff

He lived in a refugee camp for a year. The kids at first stayed with Alaksiej’s mother but then had to reunite with him: those are the asylum-seeking rules. The family spent the first six months in a filtration centre with tough conditions for primary screening: the authorities can deport you even without an interview if they think your reason for seeking asylum is not convincing. Alaksiej’s wife joined them later and the whole family was moved to a different dormitory-kind camp. They were granted a separate room with free leave and entry policy.

The family was provided with social housing in spring 2022. But then they received an asylum denial letter from the State Secretariat for Migration. Alaksiej appealed the decision in the Federal Administrative Court, but the court's decision was the same: appeal denied. Meanwhile, the reasons for the denial are the most surprising part of this story.

It was stated in both rulings that the applicant had not been subjected to repression while the mere fact of his photos appearing in the media from peaceful protests could not pose any threat. “Although the Belarusian authorities often detain opposition demonstrators for up to two weeks to suppress their activism, this does not apply to the complainant, who has never been arrested,” writes the secretariat for migration and the court (Novaya-Europe has seen the documents).

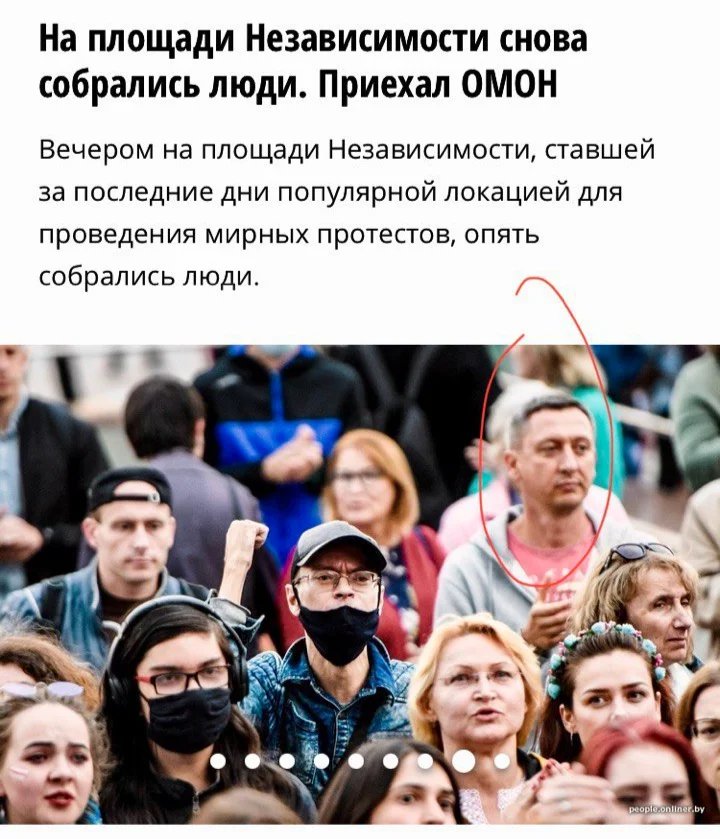

“People gather once again on Plosca Niezaleznasci (Independence Square). Riot police units have arrived”. Alaksiej Velikaselec in a picture posted on Onliner. Screenshot

“For up to two weeks” is a wonderful phrase, keeping in mind real prison sentences given for protesting. Alaksiej Velikaselec also thought that he could be blowing it out of proportion and wrote a letter to the Viasna Human Rights Centre. This was the response: “The presence of a person in photos/videos available in the public domain can potentially be a reason for initiating a criminal case under Part 2 of Article 293 of the Criminal Code (participation in mass riots). At the moment, Viasna is aware of 161 such cases when a guilty verdict was rendered.” So, these verdicts were only based on photos from the media and social networks, in which the security forces identified the participants of the actions.

There’s more about the photo identification process: “As for the alleged possibility of identifying demonstrators using facial recognition software, the analysis conducted by SEM (State Secretariat for Migration — editor’s note) shows that it was introduced by the Belarusian authorities solely as bluff."

A round of applause, please, because Switzerland joined the EU sanctions on the Lukashenka regime which means it also sanctioned Belarus’s Synesis LLC that created Kipod, a face recognition platform. The security forces (not only in Belarus but also in Russia) use it and quite successfully: “Synesis LLC provides the Belarusian authorities with a surveillance platform that can search and analyse video materials and use facial recognition software, making this company responsible for suppressing civil society and democratic opposition by the authorities in Belarus. The Belarusian State Security Committee (KGB) and the Interior Ministry are listed as users of the system created by Synesis.” Nice bluffing.

An ordinary Belarusian

The main point in this story is paradoxically not the case of Alaksiej Velikaselec and his family. As stated in the court’s decision, “the applicant failed to substantiate long-term commitment to any party or dissident organisation”. And that’s the crux of the matter. Let’s not even imagine long-term dissidence in North Korea or Iran and one backed by documents. That’s not the point. Swiss officials are right about one thing. Alaksiej is not an opposition leader or a celebrated dissident. He is an ordinary person.

He is one of the hundreds of thousands of Belarusians who rejected any compromises in the summer of 2020 and rushed into public action groups, volunteering, and to the streets to change the country.

Those who can “substantiate long-term commitment” behind bars are few and far between. But there are thousands like Alaksiej: they go out with flags, manage tiny local chats, hang red-and-white ribbons, hope for change, and end up either in prison, in emigration, or in a horrible state of anticipation that security forces may break into their homes at any moment, while propagandists urge to denounce protesters, while security force-run Telegram channels hiss: “If you are not taken away today, it means you are on our schedule for tomorrow”. And they do come. According to Viasna, 62 people were sentenced for politically-motivated criminal cases in March, while 12 people were freed after completing their terms. That’s what the statistics looks like in Belarus today.

Lawyer Vadim Drozdov. Photo from personal archives

“Swiss authorities do not recognise the scale of repressions in Belarus,” says Swiss lawyer Vadim Drozdov, who once helped the family of Vitaly and Vladislav Kuznechik, who hid for 18 months in the Swedish Embassy in Minsk. “The migration secretariat and the court did not consider the individual circumstances of the case and ignored the fact that people in Belarus are imprisoned not only for participating in protests, but also for likes, comments, and follows online. Repressions affect not only well-known politicians and human rights activists. Anyone can be subjected to arbitrary arrest if they express an opinion that runs counter to the policy of the current government. At the same time, the logic of many European officials is such that if you are a well-known politician or human rights activist you can be imprisoned. But if you are just an ordinary person, there is no threat.”

True, that’s exactly what the court ruling says: Alaksiej’s presence on images published online will not put him in danger upon return to Belarus, while the political situation in the country does not prevent expulsion in any sense.

Lost in translation from the totalitarian language

The issue does not lie with Alaksiej or the Swiss court but with the fact that the more you go west, the less possible it seems for locals — even officials who are supposed to at least read UN reports — that what happens in Belarus can be real.

Swiss nationals truly cannot comprehend what danger can be there for a person who just went out to protest.

It is difficult to understand how people can be imprisoned for photos on their phones two and a half years after these protests. How subscribing to a Telegram channel or commenting on social media platforms can land people in prison for several years. They do not understand because these things do not happen in their world, and therefore, it just cannot be happening in Europe. In Afghanistan, there are the Taliban, there’s ISIS in Syria, but Belarus is in Europe.

Photo taken from personal archives of Alaksiej Velikaselec

For instance, British journalists couldn’t believe that two KGB officers could be present in an apartment during house arrest: “This cannot happen, because private residence is inviolable.” In Europe, they in all honesty were asking the presidential candidates released after the 2010 elections: “If you were illegally arrested, why didn’t you go to the police?" It's simply unimaginable in their world, but it does happen in ours. However, attempts to convince the world of this sometimes end with the conclusion that it is just a “lost in translation” situation.

A month ago, a woman I didn’t know got in touch with me through social media. Alexey Pivovarov’s programme called Editorial about Belarus was on air then. I was one of the speakers, my interview segment was over, but the woman asked me to urgently convey a message to the producers:

“Good evening! Your programme used my photo with a poster at 40:36. I still live in Belarus and we are thrown in jail for this! They imprison people even for photos of book pages, for photos found online, an effective face recognition system has been developed and is operational. Please, cover my face somehow, it is a matter of my security and freedom! I was detained three times in 2020 and 2021, I was interrogated in the Belarusian Interior Ministry’s Chief Organised Crime and Corruption Fighting Directorate, my house was searched, the repressions have got even tougher now, and even a tiny reason is enough to get a criminal case. I implore you. The sentences are unimaginable, while the charges are terrorism, treason, and attempted power seizure. Almost all the protesters I know left the country. Please, I cannot leave, don’t expose me to unwanted danger for the sake of a pretty picture. If you need verification, I can send you pictures.”

I thank my colleagues for immediately blurring the photo of the beautiful woman with a poster. And I will not write anything else about the case of Alaksiej Velikaselec and other Belarusians whose risks are in doubt. This girl explained it better than any expert, journalist, or human rights activist. “Cover my face”.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]