Nurzia Latypova, a pensioner from the village of Iksanovo in Russia’s Chelyabinsk region, had two sons not so long ago. Her youngest son was inspired by a talk with a neighbour while fishing, left for Ukraine “to defend his Homeland”, and was killed soon after. His mother was unaware of his death. Around that time, her oldest son received a draft notice, and he was “partially mobilised”. Nurzia buried her youngest child in January 2023, and she has been trying all sorts of things to bring her other son back home since then, her efforts in vain.

Among the fallen

The main landmark in the Ust-Bagaryak rural community is the local middle school which turned 100 in 2022. A fresh-painted, spacious, and clean building provides education to 140 children. The village itself has a population of only 1,300, so it welcomes students from numerous surrounding villages and settlements.

The local headmistress gives me a tour around the school where Nurzia’s children graduated from. Each floor has photos of veterans from all sorts of wars: WW2, the Soviet-Afghan War, and both Chechen Wars…

Inside the school. Photo: Yevgeny Kulikov

“I see our country’s history is mostly represented in your school by its Soviet period,” I notice. “Where do I see any achievements of modern Russia?”

The headmistress points at two photos hanging on the wall.

“Here they are, our boys,” Fidalia Karimova, the headmistress, sighs. “There are two portraits here, but three of our graduates have already lost their lives during the special military operation. We only got the news of the third one recently, this is why he does not have a portrait here yet!”

All graduates of this school who lost their lives in the “special military operation” were volunteers. Rishat Latypov, 28, the son of Nurzia, and Alexey Kanabin, 27, served with PMC Wagner. Anfis Kashapov, 41, joined the military on 23 June 2022 and was killed on 2 July, not lasting a mere 10 days in the battlezone.

Nurzia Latypova recalls that it was said during a recent meeting at the local district administration that a total of 65 men had been drafted from the Kunashak district for the Soviet-Afghan War, of which four had been killed in action. Over 30 locals lost their lives in Ukraine during a year of war, however.

The school’s graduates who were killed in Ukraine. Photo: Yevgeny Kulikov

“When my son was leaving for the military, all our relatives said: if he is preordained to die at this age, he is going to die anyway, regardless if there is war or peace,” Nurzia recalls. “For example, my father could have died any moment when he was in captivity, but he lived a long life and returned home as he was predestined to.”

’Correct upbringing’

Ust-Bagryansk is a place mostly populated by pensioners. The local village head says there are 500 men of conscription age here, of which 31 have already been drafted: “other districts contributed fewer men, they took many from out here.”

“They were regular modest village folks,” the headmistress sighs as she recalls the deceased graduates. “Who would have thought they could become heroes or shoot other people. The war drafted them, so they took up arms. Well, I say drafted, but I mean, the war started, and they realised the country needed them. I believe we brought up these kids the right way.”

The second floor of the school building has its walls covered with countless portraits. Those are mostly people long dead, combatants in WW2, looking at kids from all around. This is where the photos of Rishat Latypov’s grandfather and great grandfather hang on the wall: both fought in that war. And now Rishat’s own portrait has claimed its spot in the row of remembrance.

“My father was captured and deported to Germany,” Nurzia Latypova, Rishat’s mother, recalls. “He didn’t like speaking about the war. He only said that he was hungry and cold all the time; captives spent their nights outside. Some local woman would give them a bit of food occasionally.”

Nurzia, Rishat’s mother, in the school building. Photo: Yevgeny Kulikov

“You have so many veterans of different wars,” I say as I stare at the portraits of the Afghan campaign fighters. “This land is kind of a soldierly one. Or is it that you cherish the memory of each warrior so thoroughly?”

“We need to cherish the memory of their heroic deeds, yes,” the headmistress says. “They did not fight in vain after all.”

“In Afghanistan?”

“So what? When their homeland called upon them, they went [to war].”

Heroes of the “special military operation” are welcome visitors here. Graduates who are now fighting in Ukraine visit their school as they come here for leave and tell the local school children about the operation and the heroism of Russia’s warriors.

“How do kids react? Do they dream of growing up as soon as possible and going to war after they attend your classes?” I ask the headmistress.

“Of course, we do not [openly] encourage them to go to war, no,” she replies. “We kind of bring them up in a way so that every one comes to this point on their own.”

“Do you have sons?”

“No. I only have daughters. But I have sons-in-law, and they are awaiting their draft notices.”

‘Who wants to conquer us? America!’

The entire Iksanovo village is one street and a graveyard on its outskirts. There are a total of 25 houses that still have tenants. Houses full of kids and joyful young people are but history these days: the local residents are mostly seniors. The “young ones” here are over 50, and there are only three children in the village.

The Latypovs’ house where Nurzia used to live a happy life with her husband and two sons still keeps the warmth of a big family. Outside, covered by mats and snow, are two cars. One was owned by Nurzia’s husband who died three years ago, and the other is the property of Rustam, the oldest son who was drafted last autumn.

Outside the Latypovs’ house. Photo: Yevgeny Kulikov

“Our mullah tells us that those who die in wars, protectors of their Homeland, go straight to heaven,” Nurzia says. “Some people are angry: what did this man die for? For some Ukraine? And why was it necessary to send our boys there? They say they died in vain.

How come they died in vain, may I ask? As an ordinary rural person, I reckon Ukraine is like a gateway to our country. So, our warriors are keeping this gateway shut with their lives so that no evil forces open the gateway to conquer us.

Who wants to conquer us? It’s America, of course!”

Nurzia recalls a recent district meeting. Some women who had lost their husbands and sons in the Ukraine war were outraged and said there was no reason to send men into a foreign country. She proudly tells me she said her piece, too — that her son decided to go to war at his own will, and added that if every man would use his wife and children as an excuse, there would be no one to protect the nation. Yes, there are people liable for conscription, but those are not enough.

Rishat Latypov was a supporter of the “special military operation” from day one, and glued a Z-symbol to his car. It took him longer to make up his mind about going to Ukraine, though, which he did after speaking with other men. First he had a talk with an acquaintance of his who served with PMC Wagner and visited the place while on leave from combat in Ukraine. He said the fact that he was alive proved that everything was going that badly there. Then Rishat met some other guys while fishing, and they said: there are lads out there in Ukraine who fight restlessly, stay in trenches for months without a proper wash while you keep sitting snug here. Nurzia believes that this talk was the decisive one for her son. He signed up to join PMC Wagner in September 2022, to everyone’s surprise.

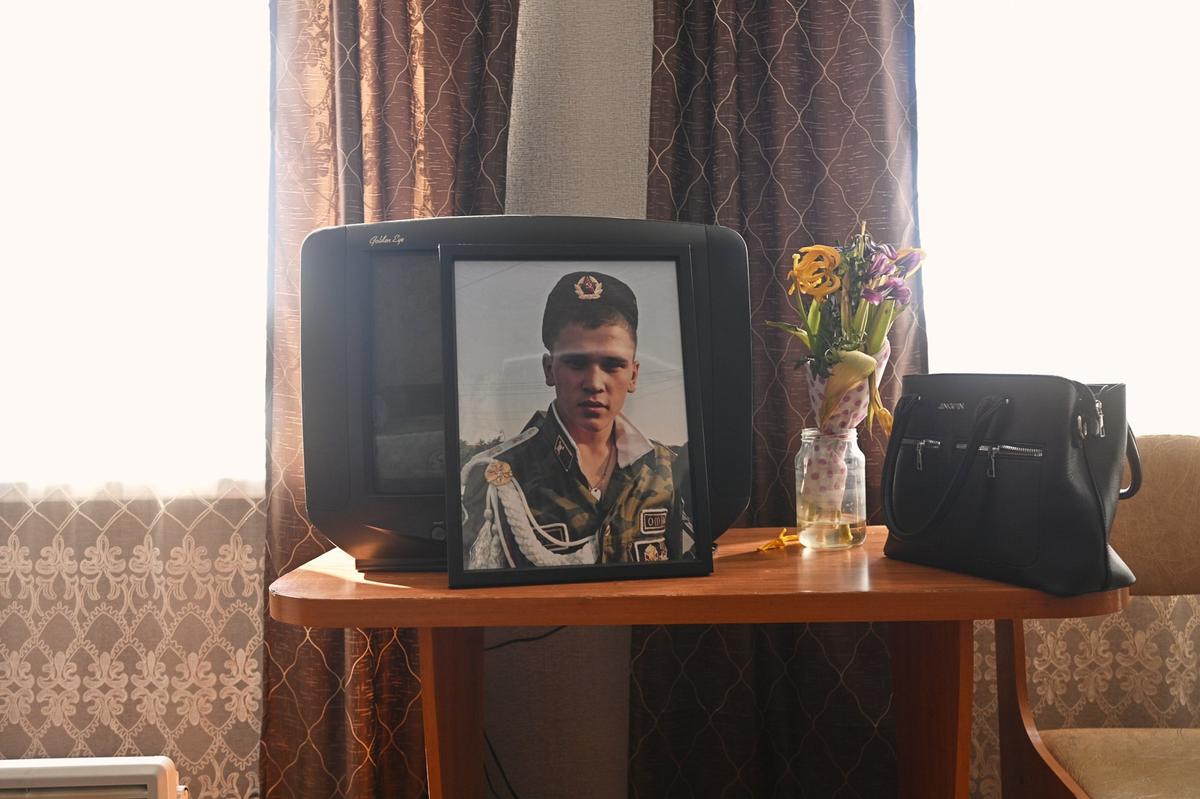

Rishat’s portrait in the Latypovs’ house. Photo: Yevgeny Kulikov

“My neighbour’s son also wanted to go to Ukraine, but they managed to talk him out of it,” Nurzia says quietly. “How could I talk Rishat out? That would never work with my son. His wife told him she was pregnant with their second child, to which he replied it was another good reason for him to get back home alive. To go or not to go was not a question for him at all. I for one thought he was doing this for the money. I asked him: ‘Why would you go? You have a family, a car, a house, and a job; you got all you need.’ But he said that he needed to ‘help the lads’, that he couldn’t ‘stay at home while they were all fighting for us’. He left for Ukraine with good intentions.”

Rishat left for the battlezone without a farewell party, said he didn’t want anyone to come. So, only the closest members of the family saw him off to Ukraine. They took a goodbye photo, and that was it.

‘We were told not to go public about our son getting killed’

Rishat Latypov was at a training camp at first, during that time he was in touch with his family. Nurzia says neither she nor her eldest son thought the “Wagnerites” would be the first ones thrown into the fray. She adds that one of her relatives is fighting in Ukraine and mentions that Rishat wanted to join him, but could not reach the man on the phone and signed up for PMC Wagner instead. He was offered an instructor position at the training camp, but the young man refused to “sit out in the rear”.

Nurzia. Photo: Yevgeny Kulikov

Rishat’s death certificate states the following: “death caused by heavy burn wounds of body parts as a result of a thermobaric shell explosion”. Place of death: the self-proclaimed Donetsk “people’s republic”. A representative of PMC Wagner told Nurzia that the location where Rishat’s group had been stationed was hit by a projectile on 22 October 2022, and the fire that followed killed almost all the combatants. It was impossible to retrieve the bodies for a long time. And even so, there was a long queue to arrange the death certificate necessary to send Rishat’s body home, so it had been stored in a refrigerator for a month. The funeral took place on 28 January 2023. The entire time, Rishat’s family had been hoping that the young man was alive and simply out of reach.

“When the zinc coffin finally arrived, we were told not to go public about our son getting killed in the special operation,” Nurzia recalls. “But why? He died on state duty. Why are we supposed to be secretive about his death? Is there some kind of threat over us? I don’t get it.”

Rishat’s family requested a DNA test certificate but were told that such certificates were not issued, and the only thing they can do to make sure is to open up the coffin and see for themselves.

“But as far as I know, my son’s body was out there in the field for a long time and turned unrecognisable,” Nurzia continues.

“What are we supposed to see there after four months following the death in a fire? To recognise his bones? We were about to do a DNA test on our own, but they told us we would only get the result in a month’s time. So, we simply took them on their word and buried him as is.”

Nurzia and her sons. Photo: Yevgeny Kulikov

A representative of PMC Wagner gave Rishat’s family 100,000 rubles [€1,100] to arrange the funeral and 5 million more [€55,300] as death reparation. In his civilian life, the deceased had a monthly salary of 35.000-40.000 rubles [€390-450]. For those two months he formally spent with PMC Wagner, his wife was paid out 300.000 rubles [€3.300], although a higher wage was initially promised.

“I never thought my son would die like this,” Nurzia says in a quiet voice. “He was athletically built, a strong, enduring, and brave lad. In his last phone call, he boasted about having tested all sorts of weapons and said he turned into some kind of Rambo. But the shell hit him from way out, and his physical abilities did not help him survive.”

Inside the Latypovs’ house. Photo: Yevgeny Kulikov

‘You give birth to them, and then they draft them and kill them’

March was a sunny, yet a cold month this year. We were lucky that the snow was still there, otherwise we would not have been able to approach Rishat’s tombstone.

“I never cry at the cemetery: perhaps my son has this calming effect on me,” Nurzia says in a voice that is barely audible. “Or maybe I just can’t believe it: I am standing here alive, and my child is there six feet under.”

Rishat on the day of his departure with his wife Viktoria at the railway station. Photo: Yevgeny Kulikov

Rishat loved his oldest daughter Darina a lot; she is now seven. Her father took her with him everywhere when they were going fishing or simply up the country. Another daughter will be born in their family in April.

“When I look at pictures of Darina posing beside her father, I always think: ‘What a happy child she used to be,’” Nurzia continues.

The adults of the family were sure that Darina was unaware that her father would never return. The girl has a doll which looks very much like a real child. One day Darina asked her grandmother to put a pair of trousers on the doll, and Nurzia struggled to put the doll’s leg through the trouser leg.

“It seems that I forgot how to deal with babies. Maybe I should give birth to another one to remember how it’s done?” the grandmother said.

“Yeah, you’ll give birth to them, raise them, and then they’ll draft them to war and kill them,” the seven-year-old girl replied.

Karina, the older granddaughter, Rustam’s child, said the following: “When mum was pregnant, grandpa died. Now auntie Vika is pregnant, and uncle Rishat died. So, enough with having children.”

“How do we live on?” Nurzia asks herself. “There will be New Year’s Eve without Rishat. Another summer, and still no Rishat. They say time is a healer, but I don’t know… I look at his photo and think: ‘Son, you’ll never grow old’. He enjoyed his life to the fullest, his career was going well, he never thought of dying so soon.”

Inside the Latypovs’ house. Photo: Yevgeny Kulikov

Letters to the son

“How do I know God heard my prayer?” Nurzia thinks aloud. “I always pray about my sons. We were in a car once with my daughter-in-law, and suddenly a huge rainbow appeared just before us. I thought God finally heard my prayers and gave me a sign that my children would be okay. Although Rishat did not respond, I wrote to him all the time; I was trying to keep the connection alive so that he could feel my love. When we were seeing him off to the train, I was filming him underhand. I couldn’t do it openly for he could have thought I was afraid to never see him again. He always called me ‘mum the reporter’.”

18 October. Hey there, my dear son. We are worried and waiting to get a call from you. I force myself to think that you are fine. You are my good boy, just take care out there. Rustam was also drafted, a month after you were. I’m feeling dreary without you boys. I just hope it’s over soon and you two are back home.

4 November. It’s a shame you will not respond to my question: how are you back there, baby? Is there no chance you can give me a call? I really hope you are doing well. I keep praying for you day and night.

22 November. It’s been a month. Today is Son’s day, so I congratulate you. Live long and happily, and all troubles will end someday. I want you to become a father to a son someday, to another little Rishat. I will love him as much as I love you.

1 December. My son, I miss you. I keep waiting for you eagerly. Love, mum.

28 December. You will soon get back home, this day will surely come. I keep waiting and loving you. See you soon!

7 January. Today is your birthday. Happy birthday! I only wish for one thing for you: to stay alive in this horrible war. Get back alive and well. I wish you happiness and well-being. Love you so much, hugs. Mum.

At the tombstone. The bullet cartridge and the cigarette were left by Rishat’s comrade-in-arms. Photo: Yevgeny Kulikov

“I work at a factory as a crane operator, and there we have a room where there’s never anyone,” Nurzia recalls. “I was there after my shift one time and suddenly I lost it and cried: ‘Rishat, get back, we are waiting for you’. It was 23 January. I thought he was lying somewhere unconscious and I reckoned he would hear my words and remember us. The next day, my daughter-in-law gave me a call, she was in tears. I couldn’t comprehend what she said, but I realised it was something about my son.”

3 February. It’s been seven days since we buried you. I can’t believe it, because you promised me you would come back. I will be waiting and hoping, I’ll keep believing that you are alive by some miracle and that you’ll get back some day.

7 February. Rishat, dearest, I love you so much, I can’t believe you’re no longer with us. But for some reason I am no longer saying hi to you. What would that mean? Please let me hear something from you. Or visit me in a dream.

15 February. Rishat, forgive me. Forgive me for letting you go to this war.

‘Mum, I never thought you’d be the one driving me to war’

Nurzia had two sons. Now, only her oldest, Rustam, is still alive. He has a wife named Riva and two children. Rustam was informed in late September that he was on the draft list. He did not receive a draft notice, though.

Rustam called the draft office to find out why he had received no notice despite being on the “partial mobilisation” list. He wanted to know if he had to get ready or not. So, he sort of forced himself in, Nurzia says.

Nurzia beside her son’s grave. Rishat is buried next to his father. Photo: Yevgeny Kulikov

Rustam is currently in Ukraine. After his mother found out her younger son was dead, she wrote a letter to President Putin: “Vladimir Vladimirovich! ...As a mother I ask you to free my son, my only son from now on, of his military duty in the special military operation and let him return to his family. He is now my only hope and the sole support not only for his own family, but also my family and the family of his younger brother. Please, help me!” The letter was sent to numerous institutions. The draft office said it was collecting papers to return the mobilised soldier from the military. Rustam’s unit was waiting for the papers, but they never arrived. The draft office said the documents had been emailed, but were not received for some reason...

The mother’s cry for help got a very formal reply from the Defence Ministry in early March. The officials noted that “military contracts signed by service members are active throughout the entire mobilisation period”.

“I hear it was one of the first letters with a complete refusal,” says Riva, Rustam’s wife. “Although two guys from Snezhinsk returned home in the past. They told us at the draft office that Rustam was added to the returnees list, and the papers were sent to his unit. And then we received the refusal letter.”

“When I was learning to drive, my oldest was worrying about me so much, and the youngest would cheer me up instead: ‘Come on, mum, hit the gas! Pedal to the floor and don’t be afraid, I’m with you here after all,” Nurzia recalls. “I got my driver’s licence after five attempts. Rishat called me, asked if I passed the exam. I wanted to do a tragic voice, but couldn’t hold it and burst out laughing. He was so happy for me and told me he woke up in the morning, thinking his mother would finally pass the exam that day. The eldest thought I would never pass it. When we were seeing Rustam off to the military, I gave him a lift to the collection point. He said: ‘Mum, I never thought you’d be the one driving me to war.’”

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]