In early April, Russia provided Belarus with an Iskander-M ballistic missile complex, which is capable of striking adversaries with nuclear warheads. Additionally, Defence Minister Sergey Shoigu has stated that some of the Belarusian aircraft can now also carry out nuclear strikes. These actions follow statements made by Vladimir Putin in late March that Moscow was preparing to supply Belarus with tactical nuclear weapons.

The US maintains military bases with tactical nuclear weapons in several EU countries, in addition to the strategic nuclear arsenals of the UK and France. Still, the Kremlin’s decision does introduce significant changes into the longstanding structure of nuclear security in Europe.

In this article written exclusively for Novaya Gazeta Europe, political scientist Denis Leven has spoken to several experts to find out what the decision to supply Minsk with the missiles truly means, how big the European nuclear arsenal is, and how we can expect NATO to respond to Russia’s latest actions.

Real threat or provocative act?

“The United States has been doing this for decades … I [and Alyaksandar Lukashenka] agreed that we would do the same without violating our international obligations regarding the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons,” Vladimir Putin said in late March as he explained his decision to deploy tactical nuclear weapons in Belarus.

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Putin has repeatedly threatened the West and Kyiv with nuclear weapons, and in February 2023 he announced that Russia would suspend its participation in the strategic arms reduction treaty. Because of Putin’s frequent mentions of nuclear weapons, his statement about Belarus was not especially surprising.

Nevertheless, the growing nuclear threats and the movement of Russian nuclear forces closer to European borders cannot but cause concern for Western countries, especially Russia’s closest neighbours. In the days following Putin’s new statement, representatives of Poland, France, and the US — as well as NATO and the EU — issued statements on the matter.

The Polish Foreign Ministry stated that the step taken by Moscow and Minsk was drawing Belarus still further into the Russian military machine and that it jeopardized non-proliferation of nuclear weapons. Andrzej Duda, Poland’s president, most likely foresaw this potential development, which is why he suggested that the US deploy nuclear weapons in Poland last autumn. Representatives of Ukraine demanded an immediate emergency meeting of the UN Security Council and appealed to the leadership of Belarus not to agree to this “Moscow-forced” step as it “would turn the country even more into a hostage of the Kremlin”. A similar appeal to Minsk was made by the head of European diplomacy Josep Borrell, who also noted that the EU was ready to respond with new sanctions.

However, the reactions of France, the US, and NATO were more restrained. The French Foreign Ministry stated that Paris condemned the plans of the Kremlin and called on Russia to “demonstrate the responsibility expected from a state that possesses nuclear weapons.” US representative John Kirby went so far as to say that the US was monitoring the situation closely but had so far not seen any evidence of the implementation of Putin’s nuclear plans in Belarus — or even of preparations to use tactical nuclear weapons against Ukrainian territory so far. NATO also stated that there was no new nuclear threat coming from Russia.

In their reactions to Putin’s statement, the Polish and Ukrainian authorities questioned whether the deployment of nuclear weapons in Belarus was legal under international law. However, Andrey Baklitskiy, Senior Researcher at the UN Institute for Disarmament Research, says there is no ground for these complaints:

“There is no treaty that prevents countries from placing nuclear weapons in foreign territory.”

The active Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons prohibits the transfer of nuclear weapons to third countries, but not their deployment on the territory of other countries while [the owners] maintain full control. In fact, the US uses the same basic logic to justify its deployment of tactical nuclear weapons in Europe.

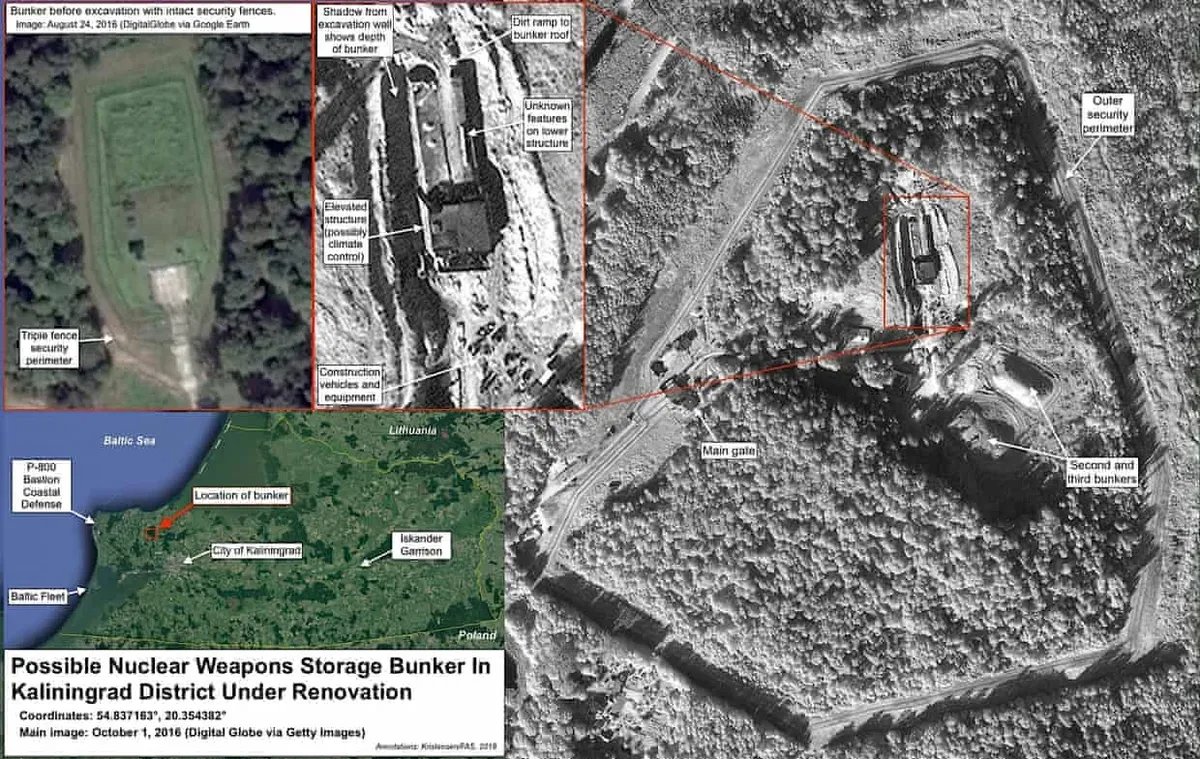

A bunker for storage of nuclear weapons in the Kaliningrad region. Photo: FAS

Even before the recent deployment to Belarus, Russia already had tactical nuclear weapons in Europe. Many have speculated that Iskander missile systems capable of using tactical nuclear weapons were deployed in the Kaliningrad region in 2018. Therefore, even if Putin follows through with the transfer of tactical nuclear weapons to Belarus, the action will not greatly affect the existing system of European nuclear security.

It does not matter if tactical weapons are deployed in Russia or in Belarus as they can still be directed at European countries, says Professor Jamie Shea, Deputy Assistant Secretary General for Emerging Security Challenges at NATO Headquarters in Brussels.

The nuclear map of Europe

The restrained reaction to Putin’s statement from Paris, Washington DC, and NATO may also arise from the fact that Europe already has nuclear weapons that can counter the Russian ones.

Approximate data shows that about 100 tactical nuclear warheads fully controlled by the US are already stationed in EU countries. They are based at Kleine Brogel in Belgium, Büchel in Germany, Aviano and Ghedi in Italy, and Volkel in the Netherlands. The US nuclear presence in Europe started in 1954, becoming part of NATO’s policy to ensure the security of its European allies. Throughout the Cold War, NATO had been using its nuclear presence in Europe to deter the Soviet Union. These days, all US nuclear weapons in Europe are B61 air bombs used by dual-purpose aircraft such as the F-35.

France’s nuclear arsenal is the second-largest of the NATO countries (after the US). France conducted its first nuclear tests in 1960, with Paris currently holding around 290 warheads at its command. Most of them are deployed on ballistic missiles used by four Le Triomphant-class submarines, which have been in French service since the late 1990s. All four submarines are stationed at the Île Longue naval base in Brittany. The rest of the warheads are mounted on air-launched cruise missiles. These missiles require 40 land-based multi-role fighter aircraft and 10 sea-based ones to launch. Ground-based fighters are stationed at the Saint-Dizier air base 190 kilometres from Paris. Sea-based fighters are stationed on the only French aircraft carrier, the Charles de Gaulle, in its home port of Toulon.

The third NATO country with its own nuclear weapons is the UK, which acquired its first weapons in 1952. By the turn of the 21st century, however, the United Kingdom had reduced its nuclear deterrence arsenal to a minimum, with 225 nuclear warheads at its disposal. These warheads are designed to be used with Trident sea-launched ballistic missiles; they are deployed on four Vanguard submarines, each capable of carrying 40 warheads. One of the submarines is constantly on permanent alert at sea, two more are at the Clyde Naval Base in Faslane in Scotland, and one is currently undergoing repairs.

Therefore, despite the fact that Russia has the largest nuclear arsenal in the world, there are at least as many nuclear weapons in Europe, and these are also constantly being modernised.

Support independent journalism

Political answer to the nuclear question

“Nuclear weapons are first and foremost political weapons,” Andrey Baklitsky says. The possibility of a retaliatory strike — catastrophic in its consequences not only for the enemy army, but for the entire country and its population — is used as a deterrence factor. This is why Baklitsky believes that decisions like the deployment of nuclear arsenals in Belarus should be considered a political gesture. Putin is demonstrating to Western countries that his foreign policy ambitions are serious, and he may be willing to receive some kind of response signal.

At the same time, one should not think that “nuclear diplomacy” rules out the possibility of a real nuclear conflict completely. Although nuclear doctrines, including the Russian doctrine, allow nuclear weapons to be used only as a response to, or in the event of, a threat to the existence of the state itself, the very participation of a nuclear power in an armed conflict (as is the case with the war in Ukraine) already increases nuclear risks, Baklitsky notes. In addition, three other nuclear powers, the US, France, and the UK, are also indirectly involved in the conflict in Ukraine.

Statements from representatives of the Russian elite underscore this risk. In addition to repeated speeches by the Russian President himself, Secretary of the Security Council Nikolay Patrushev has mentioned that the Russian side might potentially use nuclear weapons. Dmitry Medvedev, the Deputy Chairman of the Security Council, has spoken of a “nuclear apocalypse”. Even Ramzan Kadyrov, the governor of Chechnya, threatened to use tactical nuclear weapons. Although none of these politicians or officials are authorised to make decisions regarding the use of nuclear weapons, the rhetoric of these public figures increases the chance that both sides will take the threat of a nuclear war seriously, as was the case during the Cuban Missile Crisis — and in the early 1980s.

Therefore, although Putin’s decision does not technically change the balance of power, it is a symbolic step that could lead to an additional aggravation of the situation, Jamie Shea believes. In this sense, NATO’s relatively muted reaction is a good sign as it demonstrates that the Alliance is self-confident, the expert believes.

Boeing B-52H with weapons, Barksdale Air Force Base. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

NATO has enough nuclear capability to respond to Russian threats using its existing capacities, Shea says. It can deploy additional US nuclear bombers, such as B-52s, B-1s, and B-2s, to European military bases using rotation. It can also move some of its warships closer to Europe, like Aegis-class destroyers. Those can be effectively used for missile defence in the Baltic Sea or the North Sea. Another option is more active modernisation of B-61 ballistic bombs, a process that has already begun. In particular, Germany reported purchasing a large batch of new American F-35 multi-role fighters that are capable of carrying such bombs.

NATO is unlikely to change its nuclear stance in Europe in response to Russian actions, Shea says.

However, Western countries are still likely to take responsive measures of a political nature. In particular, the US will have to do something about the emerging strategic threat created by Russia’s withdrawal from the New START treaty. Additionally, Shea believes it is important that the West conveys to the Kremlin the consequences of a potential violation of the ban on nuclear weapons (which was developed after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki). At the same time, if nuclear weapons are used not against a NATO country, but, for example, against Ukraine, NATO can respond using conventional weapons.

The deployment of tactical nuclear weapons in Belarus raises the stakes in the political confrontation between NATO and Russia, but the European nuclear balance will not change. NATO’s composure in responding to the threat shows that the Alliance believes Putin is trying to provoke the West into further escalation. Washington and Brussels are unwilling to fall for it, at least not yet. Nevertheless, Europe still has the opportunity to respond by strengthening NATO’s nuclear presence in the EU member countries.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]