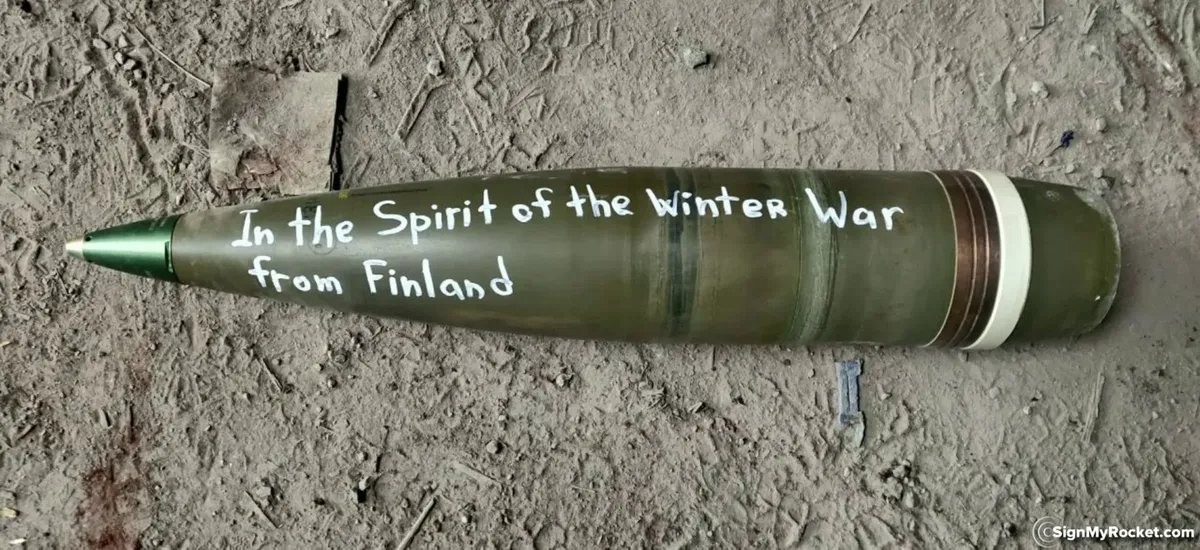

A message on a shell referring to the Soviet-Finnish (Winter) War. Photo: Signmyrocket

From Finland with love

On Christmas Eve 2022, Martti J. Kari, a professor at the University of Jyväskylä and former deputy chief of intelligence of the Finnish Defence Forces, tweeted a picture of a 155mm artillery shell with the caption “Merry Christmas from the Kari family”. This inscription was placed on the shell at his request and for a donation to the Ukrainian army by the volunteer service SignMyRocket, which collects donations for the Ukrainian Armed Forces. Other well-known people in Finland, including Jussi Halla-aho, chairman of the parliamentary foreign affairs committee, and writer Sofi Oksanen, have also announced their participation in the project. With their help, hundreds of Finns have already sent “a death greeting” to Russia, as the journalists of Finland’s largest newspaper Helsingin Sanomat aptly put it, for a total of more than 140,000 euros.

Shell messages are bought by people from all over the world, but Finland, though small in size, stands out against this backdrop too.

“Finns are the only ones who send messages of retaliation,” the project coordinator told YLE journalist Maxim Fedorov. On the shells they are asked to write, for example: “We will never forget 1939”, “In the spirit of the Winter War”, “Between the eyes. With respect, Mannerheim.” The latter inscription is a reference to the famous wartime song Silmien välliin, meaning ‘Between the eyes’, which includes the words: ‘Between the eyes, Ryssä [a Finnish derogatory term for a Russian person — translator’s note], and it will be the end of him’. Professor Kari also said that he had bought the inscription in memory of his father, who was wounded by Soviet grenade fragments on the Karelian Isthmus in February 1940.

A table that got evacuated twice

Russia’s attack on Ukraine shocked the entire civilised world, but Finland has old scores to settle with its eastern neighbour. “The news of the war instantly brought us back to our own history,” says Finnish writer Ewa Olandt. Immediately, an old wound that seemed already completely healed opened up — the trauma of the Winter War, as Finland calls the Soviet-Finnish War of 1939-1940. Soviet poet and writer Alexander Tvardovsky called that war “unremarkable” and was absolutely right: it did not bring any glory to the Soviet Union, having started with provocative shots near the village of Mainila, but the multiple advantages of the USSR in manpower and especially in equipment led to a fivefold, according to cautious calculations, excess in the number of dead.

And the goals of aggression could not be disguised in any way — the Soviets were immediately expelled from the League of Nations as aggressors. The terms “sisu”, i.e. unbending Finnish character, and “Molotov cocktail” became known around the world. The murdered men were taken to cemeteries in their home parishes, and it was done by women: members of the paramilitary organisation Lotta Svärd, denigrated by Soviet propaganda, which called it a fascist-type organisation.

Finland lost about 10% of its territory and its fourth-largest city, Vyborg. From Lost Karelia, as these lands are now called, some 430,000 inhabitants were evacuated deep into Finland.

…When we come to visit friends in Helsinki, we are seated at a table — an old, white-painted, large dining table. This table is not an ordinary table — it’s an honoured one: it was evacuated twice with our friend Martti’s parents. In the winter of 1940, it arrived in Ostrobothnia (west Finland — editor’s note) from the Karelian Isthmus and returned there in early 1942. By this time, the Continuation War, as Finns call the period of World War II which began on 25 June 1941 with the massive Soviet bombing of Helsinki and other towns in Finland (after which Finland fought on the side of Germany and its allies) and ended on 19 September 1944, with the withdrawal of Finland from the war with the Soviet Union and the signing of an armistice.

During the Continuation War, up to 260,000 evacuated Finns with their livestock and furniture returned to their homeland on the Karelian Isthmus and restored peaceful life there: the destroyed houses and railways were restored, and the post office, shops, banks, schools, medical centers, and church parishes were reopened. The second evacuation of the Martti family (and the table with them) happened in June 1944 when the Red Army began a counter-offensive in the direction of the Karelian Isthmus. At that time Finland lost this part of Karelia for good and the table was permanently settled in its new location. A living, tangible memory.

Finnish soldiers crossing the border into the USSR, summer of 1941. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Memory traversed by feet

In Finland, unlike in the USSR and Russia, remembrance is treated with reverence.

“We are a small nation, we can’t live by the principle of ‘women will give birth to new ones’,” explains Finnish journalist Anne Kuorsalo to Novaya-Europe. Anne is the daughter of evacuees from Muolaa parish (former Finnish parish on the Karelian Isthmus, now Krasnoselskoye Rural Settlement, Leningrad Region — editor’s note) and was born after 1945, but the war and evacuation occupy a large place in her life and professional activities. She — alone and in co-authorship — compiled and published several books of memoirs: “Childhood Wounded by War”, “Evacuated Children”, “The Long Evacuation Trip”, “The Evacuation Road” and “So Muolaa Stayed Alive”.

The Muolaa Society, an organisation that first brought together former residents of the municipality of Muolaa on the Karelian Isthmus and now brings together their children and grandchildren, published the latest book at its own expense. There are many similar societies in Finland:

The inhabitants of each parish in the Lost Karelia have set up their organisation to preserve themselves as a community, to preserve the spirit of their homelands, their history, their language, and their traditions.

Or even their heritage.

In pre-COVID and pre-war times, members of these Karelian societies often travelled to their ancestral homeland. Nostalgic “foundation-tourism”, as these trips to the native stones were called (the foundations are sometimes the only thing left of the Finnish houses in Karelia), were eventually replaced by practical matters: descendants of the evacuees tidied up cemeteries, erected memorials, organised memorial days, delivered lectures to local residents and engaged in other activities described as “folk diplomacy”.

The territories that the USSR acquired after the Soviet-Finnish War of 1939-1940 and the Soviet-Finnish War of 1941-1944 are marked in red. Photo: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0

The same Anne Kuorsalo came up with a project called Evakkovaellus, or the Evacuation Trip, implemented by the Muolaa Society. Every year (before COVID and the war) on a designated day, members of the society set off on foot and with their belongings on a difficult journey of several kilometres, the children and grandchildren of the evacuees trying to literally experience and understand: what it is like to be expelled from your own home, to leave with your children and what little belongings you can carry.

Experts write that the trauma of evacuation is not experienced by one generation. With the outbreak of war in Ukraine, these — not their own, but their parents’ — memories struck with renewed force.

“My father was born in 1927 in Harlu, and my grandfather in Suistamo. My mother-in-law’s family came from Terijoki and Kaukola Riaisala,” writer Eva Olandt said at a Christmas party for refugees from Ukraine organised by the Harlu Society. “When a bomb landed in a crowded Ukrainian railway station and killed a huge number of civilians, my husband and I remembered how my five-year-old mother-in-law and her mother were on the train that was bombed at Elisenvaara in 1944. They survived. Or when we read how Ukrainian houses were looted and desecrated, we know that the same thing happened when my family returned to their home in Karelia in 1941. In this sense, we are comparing the fates of our countries in a very concrete way”.

Support independent journalism

From disaster to a miracle

War graves — Hero Cemeteries, as they are called in Finland — are found in every church parish. The monuments in these cemeteries are never typical and are often created by famous architects and sculptors, such as the Cross in the village of Pusula, sculpted by the young Eila Hiltunen, who later became famous for the Sibelius Monument in Helsinki. In the last three wars — counting the Lapland War of 1944-45, when Finland was at war with Nazi Germany under the terms of the armistice, the country of 3.7 million people lost about 90,000 dead and about 200,000 wounded.

“Almost every family was affected, if not themselves, then their relatives or neighbours,” says Anne Kuorsalo.

After the war, the country — whose industry, as the self-ironic Finns aptly put it, stood on one leg, and even that was wooden — paid out about 400 million dollars worth of goods in reparations.

The volumes are staggering: war reparations accounted for up to 16% of public expenditure. Finland delivered more than 600 ships to the USSR in six years, and 345,000 railway wagons were needed to carry all that was sent in reparations. The Finnish media calculated that if lined up in a row, this train would stretch from Moscow to the Urals.

And then the devastated country made the leap to a welfare state. “Miracles don’t happen — people make them,” Eva Olandt put it poignantly when describing how the Finns rebuilt their country. According to the writer, the same miracle can be performed by Ukrainians. “You Ukrainians can be sure that almost every Finn is praying for you every day and is actively involved in helping Ukraine!” She is not exaggerating: “Finns’ support for Ukraine never wanes,” reads a headline on the website of the state-run media company YLE. Almost 90% of the respondents support the economic sanctions against Russia, and 80% of the respondents are in favour of hosting Ukrainian refugees in Finland. Aid to Ukraine has been collected by famous artists at large charity concerts and by Finnish grandmothers at small provincial charities.

Finnish PM Sanna Marin’s interview with CNN. Photo: screenshot of the video

Russia’s attack on Ukraine has radically changed public opinion in Finland and the rhetoric at all levels. The war in Ukraine put an end to the policy of Finlandisation, i.e. looking towards a large and influential neighbour (Finlandisation is a negative term that characterises Soviet-Finnish relations after World War II, when Finland’s policy, while nominally maintaining sovereignty, was subordinated to that of the USSR — editor’s note).

Finland no longer hopes for good-neighbourly relations and sends deadly greetings worth hundreds of thousands of euros to the aggressor attacking Ukrainian cities. Finnish Prime Minister Sanna Marin said in an interview with CNN that Ukraine must surely win the war against Russia. “And we have to make it a reality.” This is not unsubstantiated: Finland’s total military aid to Ukraine amounts to 750 million euros, according to the Finnish government’s website.

Ukraine’s victory will be celebrated in Finland — at this twice-evacuated table, too.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]