Last weekend, an online benefit conference “What Good Is Philosophy?” was held in order to raise the funds required to establish a Centre for Civic Engagement at Kyiv Mohyla Academy. Amongst the speakers were novelist Margaret Atwood and scholar of Ukrainian history Timothy Snyder, as well as Ukraine’s public intellectuals, Mychailo Wynnyckyj and Volodymyr Yermolenko.

In the wake of the conference, Novaya-Europe interviewed one of the speakers, Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Oxford Jeff McMahan, who studies the morality and ethics of war. We spoke about what a just war is, whether it is possible to sympathise with the mobilised soldiers, and whether anti-war Russians should donate money to fund the purchase of drones for the Ukrainian army.

Jeff McMahan

White’s Professor of Moral Philosophy at the Department of Philosophy, University of Oxford. Professorial Fellow, Corpus Christi College

At some point it seemed like wars became a thing of the past (at least in the Global North), while progress and non-violence triumphed. But now it feels like the wars are back and we need to reflect upon them once again. What can philosophy teach us about wars?

War has not gone away. Even in Europe in the later 1990s, there were wars in what used to be Yugoslavia, and there were wars in Chechnya. Russia has fought smaller-scale wars in Georgia and Crimea. Wars have been very much present in the Middle East and Africa and other areas. When wars are far away, we pay less attention to them. But many people are still being killed in wars in various places.

What some philosophers and legal theorists are trying to do is to better understand the morality of war, when it might be justifiable to resort to war and when it’s unjustifiable to do so. There’s a long tradition of thought about this, known as the just war theory.

Very few people think that any form of violence is unjustifiable. Most people believe that if I see a man about to murder a small child, I am not only permitted but required to use force and violence if that’s necessary, to prevent that person from murdering the child. Children are being murdered in Ukraine right now. And we have to think about what can be done about that.

Some people are involved in war professionally, that is, soldiers. For them, it’s most important to think about the morality of war because they are the ones who are called upon to do the things that are done in war. For instance, in the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, and in many other countries, people who go through the military academies on their way to becoming officers do tend to study the morality of war. It’s certainly true at the United States Military Academy, the United States Naval Academy, the United States Air Force Academy. Michael Walzer’s book Just and Unjust Wars, which has been around since 1977, is a regular part of the curriculum at all of these academies.

Putin as well as other Russian officials have spent a lot of time trying to rationalise and justify the war in Ukraine (or, as they call it, “special military operation”). A lot of their arguments come down to the fact that Russia is defending itself, not attacking anyone. Why do they insist on this line of argument? Is it because the only just war in the 21st century is a defensive war?

It is widely believed, and to some extent, this is true in international law, that the only justifiable war by a state is a war of defence against someone who is attacking that state. It doesn’t have to be another state because states claim the right to defend themselves against what are called non-state actors, too, for instance, terrorist organisations.

There’s also a doctrine of collective defence, according to which if one state is unjustly attacked, other states are permitted to come to the defence, particularly if there are prior treaty commitments. All of this is part of international law and the law of armed conflict.

I would say that for many years there has been a rough consensus among just war theorists that the only permissible resort to war is in response to an attack against the state. But there are exceptions to this, particularly in the doctrine of humanitarian intervention.

If the government in a state is attacking or persecuting its own people or some segment of its own population, it is often thought to be permissible morally for another state to intervene to protect the people who are being attacked.

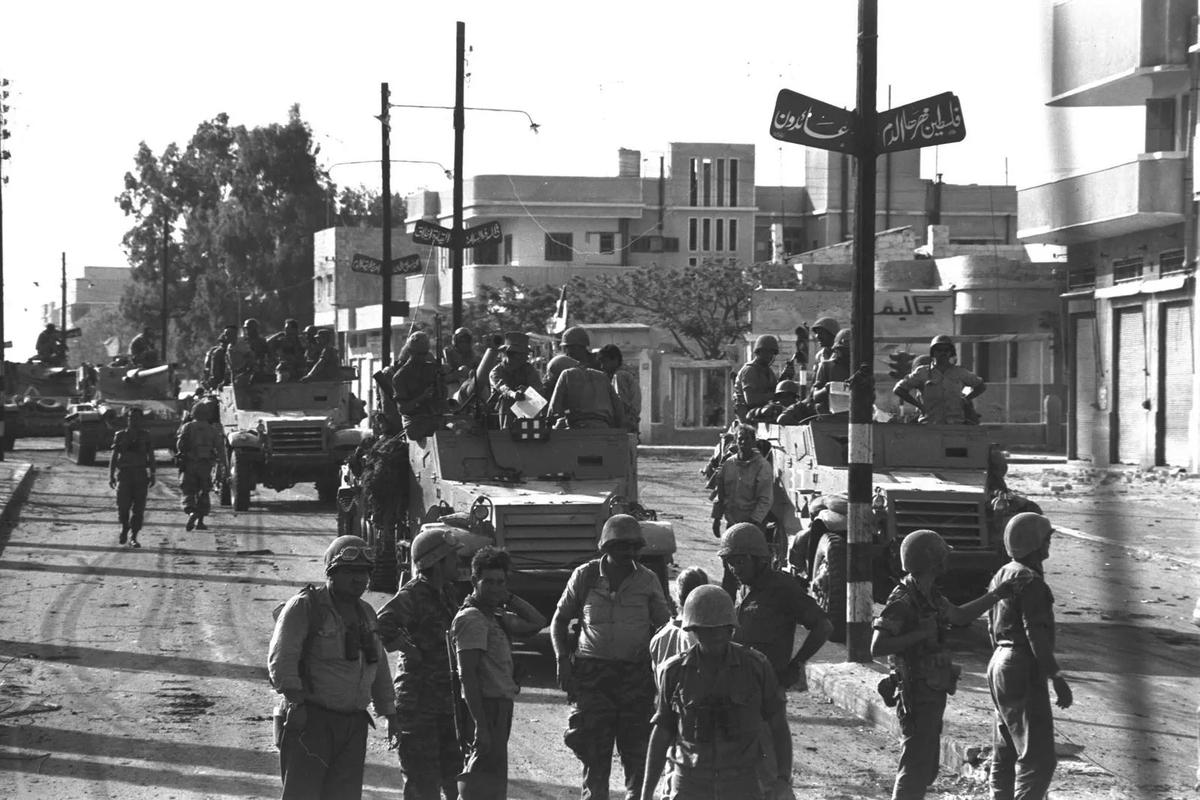

Six-Day War in Gaza. Israeli armoured troop unit entering Gaza during the Six-Day War, June 6, 1967. Photo by The State of Israel Government Press Office

Now, Russia has not been attacked by any other state. There is a notion of pre-emptive war, which is when a state X goes to war when an act of aggression against it is imminent. That is when the forces are mobilising on the borders. For example, in 1967, when Arab states were mobilising forces to attack Israel, Israel pre-emptively attacked those states. And that’s what’s considered pre-emptive war. But again, there was no mobilisation of forces for attacking Russia, so it couldn’t be justified as a pre-emptive war.

There’s also a doctrine known as preventive war, which means states perceive some threat that is imminent. What Kremlin officials have to claim is that there was evidence that at some time in the fairly near future, Russia was going to be attacked through Ukraine or by Ukraine. What’s the evidence for that? There doesn’t seem to be any. Apart from the fact that there had been some discussions about whether it might be possible for Ukraine to join the European Union and possibly even NATO.

I think to the extent that the United States and NATO countries allowed that idea to circulate, they have been irresponsible. The US and European countries ought to have said explicitly, “No, we are not going to make any move to admit Ukraine to NATO, we will not deploy NATO weapons in Ukraine.”

I don’t think the failure of the United States and Western European NATO countries to make that explicit declaration justifies what Russia has done, because I myself don’t believe that there is any prospect of Ukraine joining NATO at least for the foreseeable future. But still, I do think that it was wrong and irresponsible for the US and Western European NATO countries not to make that declaration, thereby giving leaders in the Kremlin a kind of excuse for launching this war of aggression against Ukraine.

Support independent journalism

In Russia, the debate on how to treat mobilised soldiers is ongoing. Some say they are war criminals, but others claim they also are victims of the Russian regime. Can one empathise with mobilised soldiers?

It’s a difficult question because the pressures that apply to any particular individual soldier vary. I think most of the time soldiers or combatants who fight in unjust wars have excusing conditions. That is to say that we shouldn’t regard them as evil criminals. We should, of course, if they commit atrocities of the sort that are occurring in Ukraine.

There are two questions here. One, the fundamental question — is what they do permissible? The other question is to what extent are they blamable or culpable for what they do? I would imagine that many of the soldiers from Russia who have gone to fight in Ukraine have believed the lies they have been told by their own government. “Ukraine poses a threat, the Ukrainian government consists of Nazis who are persecuting Russian-speaking brethren, and we have to go save them, this is a humanitarian intervention.”

Another [lie] is that this is a war of defence because Ukraine posed this grave threat to Russia. Some of the soldiers may believe that. And to the extent that they believe that and are motivated by the sense that they are actually defending innocent people, then they are perhaps not blameworthy. Except insofar as they ought to be more sceptical about what they are told by a government that clearly controls most of the media and has shut down a lot of media and internet access.

If your government does that, you have to wonder why. Why won’t they let you hear information from somebody else? And why if you refer to what Russia’s doing as a war, you might go to jail? People should ask themselves, do we really believe what we’re being told? If the penalty for not believing is so harsh.

Some soldiers fight because they are deluded, because they believe lies, because they don’t know the truth. Others fight because they are compelled by threats and pressure. They worry what’s going to be done to them and their families if they don’t go.

This happens, of course, not just in Russia. It happened in the United States during the Vietnam War and other wars that the United States has fought in. In all wars, soldiers are deceived, manipulated, pressured, coerced, and they often fight under duress. One can, to some extent, empathise with them. They are, in one way or another, victims as well.

The people one cannot empathise with are the political leaders who set all this in motion, who are responsible for this mass killing of innocents and continue to stand up in front of the world and lie and pretend that they are good people when they are mass murderers.

Interment for 300 unidentified victims of communist occupation of Hue in 1968. Photo by United States Army

How is this “supporting the soldiers dilemma” solved in the US? In the US, the anti-war movement never seems to be explicitly hostile towards their soldiers. Activists speak out against the war but the society does not seem to be ready to condemn their troops. At the same in Russia, anti-war activists frequently support the idea of donating money to the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

Perhaps protesters against the Vietnam War ought to have done that [donated money to the Vietnamese army], at least as a way of trying to make reparations to the victims of what I think of as American aggression. Some people in the United States did condemn the soldiers. Many did. Many of the Vietnam veterans felt at the time and probably continued to feel some great resentment against their fellow citizens when they came back. They were jeered at and mocked and persecuted when they returned. I think it’s inconsistent for citizens to do that to the soldiers unless they are also willing to do it to their fellow civilian citizens who support the war and don’t protest against it.

If people are going to condemn the soldiers, they need to also condemn all those who refuse to repudiate what the soldiers are doing or who support what the soldiers are doing, because, as I said, the soldiers are acting under duress. They’re acting under extreme pressure.

The civilians who support the war may be morally far more culpable or blameworthy than most of the soldiers.

Any action of any sort, violent or non-violent, taken against people because of their contribution to a war or support for a war, has to be justified in defensive, not punitive terms. It shouldn’t be regarded as punishment and it should be done only if it can have the effect of stopping the war, reducing the level of violence. So any action directed towards anybody in the course of a war needs to be justified by its effects. Which is not to say that the effects are the only thing that matters. But people who may be guilty, Russian civilians who actively support this war and go around putting Zs everywhere, they may be guilty, but nothing harmful should be done to them unless it promises to increase the probability that the war will end soon.

So I think economic sanctions can be justified even though they harm civilians. The harms are relatively slight. But that communicates something to people. And if it makes them less supportive of the war, then it may be justified.

What if the sanctions just make Russians hate the West even more?

If it has that effect, then it ought not to be done, it’s self-defeating. I’ll give you a good example of that. Some say that Russian forces were attacking power stations and energy supply units in the cities to deprive [Ukrainian] people of heat, food, and water because the plan was to demoralise the population and make them pressure their government to stop resisting and to make conditions so bad that they would be willing to end the war in a way favourable to Russia.

Now, that seemed to me, if that’s true, so obviously and clearly self-defeating. It just makes those people hate the people who are doing this to them.

If corporations and governments impose sanctions and deprive ordinary [Russian] people of things, it should make them think “Why does everybody in the world think that what we’re doing is wrong? Why are they all doing this to us? Why are we so isolated? Why are we not getting support if what our government is telling us is true?”

Economic sanctions are less likely to be self-defeating than Russia’s bombings of energy plants in Ukraine. The same way the Nazis bombings of civilian areas in England during the Second World War were clearly self-defeating. They were meant to lower British morale. And the same is true of the British destruction of German cities. This was supposed to demoralise the people, but in both cases it doesn’t have that effect. It makes you hate the people who are doing this to you and want to resist them.

Russian people stand in line to enter H&M store in the Metropolis shopping mall in Moscow, Russia, 03 August 2022. Photo by EPA-EFE/MAXIM SHIPENKOV

This war uses a lot of drones. This seems to be one of the most studied topics in the philosophy of war. How does the use of drones affect the ethics of war?

In the war in Ukraine, the drones are autonomous, pre-programmed to attack particular targets but they are pilotless. So what that means is that they can be used without any danger to those who are using them. They can be sent from a long distance.

Now, some people have thought that that was really important because they have thought that the only justification for using force for a soldier is using force as self-defence. So a soldier is there on the battlefield, and they can kill other soldiers because they are threatened by the other combatants. But a drone operator may not be under threat because the drone operator is somewhere entirely safe. So some people have thought that this undermines the justification for the use of force in war, because the people who are using the drones aren’t defending themselves. But I think that’s a mistake because the justification for the use of force in war is not individual self-defence by soldiers. It is to achieve the just aim of the war, which in this case is to preserve the self-determination of the people in Ukraine, those who want to not to be living under Russian domination and control.

Some criticise the West for sending weapons to Ukraine. They argue that a diplomatic, non-violent solution is needed instead even if it will result in the loss of territory for Ukraine. Others, at the same time, call for more military equipment. So it all comes down to what the West does essentially. To what extent is it responsible for the outcome of this war?

If the provision of more and better weapons by the West to Ukraine doesn’t increase the risk of nuclear war, if it helps to bring about the best outcome, which is complete Russian withdrawal, then yes, the West should provide those weapons.

I do think any outcome of the conflict that concedes unjust gains to Russia will be an undesirable one and it will be terrible for the people whose territory, whose lives are destroyed by that solution.

That is, people who want to be Ukrainians don’t want to be under Russian control, but their houses would be in the territories that Russia would take and control and would become part of Russia. Those people would either have to become Russians and live under Putin or leave their houses and become refugees, it’s a horrible outcome for some people.

So far the provision of weapons has been good in the sense that it has prevented Putin from achieving an easy victory, which is what everyone speculates he thought he would get. To the extent that the provision of more weapons to Ukraine helps to preserve Ukrainian sovereignty and helps to make the costs of continuing the war increasingly burdensome to Putin and the other officials in the Kremlin so that they would be willing to compromise more, then I think the effects of the provision of weapons are going to be good.

I have to add that the essential element of ending the war is that the NATO countries will make a pledge not to admit Ukraine to NATO. It’s clearly a source of paranoia for people in Russia to have NATO’s enemy forces on their border.

Continuing on with the war would result in more people dying.

I don’t disagree with that. On the other hand, you have to consider the autonomy of these [Ukrainian] people as moral agents. It seems to be the case that the vast majority of people in Ukraine don’t want to surrender, they would rather risk their lives with the continuation of the war.

We don’t know exactly what all the Ukrainians want, but to the best of my knowledge, nobody is reporting dissatisfaction, protests, saying to Zelensky, “Surrender, capitulate, negotiate, let’s stop this war.”

It doesn’t seem reasonable for people in Ukraine to have to sacrifice their self-determination to avoid having to kill more Russian soldiers. The Russian soldiers may be the people who are least desiring to sacrifice their lives.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]