The Pre-Trial Chamber II of the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague has issued an arrest warrant for Vladimir Putin and Russia’s commissioner for children’s rights Maria Lvova-Belova. As per the court’s website, both are “allegedly responsible for the war crime: unlawful deportation of children from occupied areas of Ukraine to the Russian Federation”. What country may Putin be arrested in? We talked to Gleb Bogush, an expert in international law, to find out.

Why did the International Criminal Court start with this case, the one on unlawful transfer of children and unlawful deportation?

Gleb Bogush

an expert in international law, PhD in Law

a postdoc with the University of Copenhagen

From the very start Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine when the deportation of children was revealed, it was considered to be the most obvious reason for persecution. Additionally, the ICC gives priority to investigating crimes against the most vulnerable groups, including children. This is a pretty clear accusation, and I think the court has reasonable grounds to believe that the crimes in question were indeed committed, and that these two people are responsible. Also, this has been long discussed, so I tend to think the court has picked their best option.

It must be really hard to prove those crimes, right? The children that were displaced to Russia are held in orphanages and care homes, and there is no access to them. Those who transport those kids probably have a rather logical explanation: children should not be left unattended while the places they live in are being bombed and shelled.

There are clear provisions of the international humanitarian law that prohibit doing such things. Russia is a party to the Geneva Conventions, so it must abide by those regulations. Here is one thing I’d like to point out: there have been calls from various states and international institutions, such as the UN, urging Russia to put an end to this practice. Besides, the arrest warrants remain classified, they have not been published.

But there is information about the warrants on the court’s website, isn’t there?

Not quite. There are two options with warrants like these. The first one is a public warrant. This was the case of Omar al-Bashir, the former president of Sudan: there was a full procedure and a long 200-pages decision. Another option is a non-public warrant, and we do not know for certain how many warrants were actually issued: there might be more than two.

In our case, the middle ground was found, and one of the reasons was to protect the potential witnesses and victims who apparently would testify if the case actually goes to trial. The decision was made not to publish the warrants themselves, but to make an announcement on what kind of charges were filed against the two people. That is, the court decided to reveal that there are such warrants, but kept their contents secret. This is why we may only presume many of the things we are now discussing. We do not know, for instance, what kind of evidence the prosecutor is relying on.

Does the announcement that there are such warrants mean that the prosecutor has some kind of evidence already?

Yes, it certainly does. I believe that the fact that the warrants have already been issued means that there is enough evidence collected by this point. It is important that the decision was made by judges who considered the prosecutor’s motion. Such decision follow a well-defined procedural form, and the judges rely on certain regulations, which are quite strict. There were instances when judges used to reject warrant requests, like on early stages of an investigation. This is not done automatically, prosecutors do not issue warrants, those are issued by the judges who consider evidence submitted by the prosecutor.

I need to remind you that the ICC is not the only body that is investigating the crimes. Many states are engaged in investigations, and it appears to me that a lot of information has been collected.

Russia has already responded in its regular fashion: we do not give a damn about your court, it has no rule over us, we never joined the Rome Statute, so, we don’t care who you are.

By the way, it is true that Russia never joined the Rome Statute despite the fact it had signed it. This is a peculiar situation: one of the suspects here is a person who ordered to sign the Rome Statute some time ago.

However, Russia has no obligation to cooperate with the ICC. So, in legal terms, the response was correct.

Russia signed the Rome Statute but did not ratify it?

Not only did it not ratify the treaty, but it simply announced it was not going to become its party. Media and other non-legal sources often call this “a withdrawal of the signature”, but in reality, Russia simply stated that it was not going to become a party to the ICC. Actually, it might change its mind and join at any moment. Remember, Alexander Bastrykin, the head of Russia’s Investigative Committee, used to promote the ratification of the Rome Statute and wanted this to happen as soon as possible back in the day.

Alexander Bastrykin. Photo: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0

He must be regretting that now.

He said it in an interview, and I believe that it is still available online. I mean, the situation is developing, and many things we used to consider unthinkable are becoming reality. I wouldn’t make any guesses on how this situation is going to develop.

Is there any development possible? It is hard for me to imagine what this would look like in reality.

So far it is true, I agree.

I do not see a realistic scenario of how these warrants may be executed at this moment.

But the court’s objective is to investigate the crime. And then it’s up to the countries, including the Russian Federation. Do you believe that the current situation would last forever? I believe it’s not looking great right now, and nobody’s happy with it, but nothing lasts forever.

When it comes to international crimes, there is no statutes of limitations. We do not know so far when the trial is going to happen, who will be the accused, and if they will actually be called to the bench. But the main goal of everyone involved in this process, including professional lawyers, is to do their job. Be it judges, the prosecutor, or officials, they all abide by the law. A court decision may be tactically correct or incorrect, but my opinion is that the court has been staying silent for a year, and many people started asking questions, forcing the court to take certain actions. The court cannot arrest anyone or forcibly bring someone to The Hague, but there were all sorts of situations throughout history. Some of the defendants even arrived at the court themselves.

Vojislav Šešelj. Photo: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0

Of their own accord?

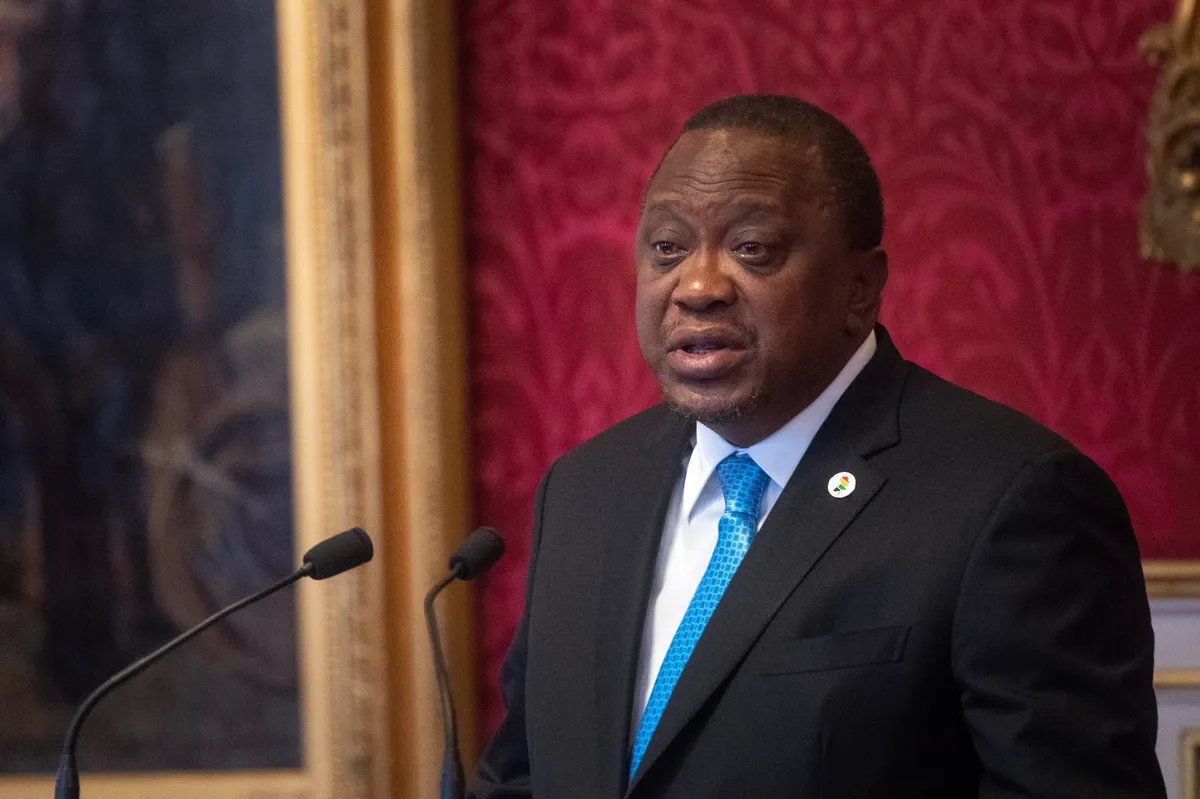

Yes, exactly. Vojislav Šešelj came to the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia all by himself. Uhuru Kenyatta came to the ICC himself while he was still an acting president of Kenya, and he remained in this position for some time despite being accused of crimes against humanity.

Was he acquitted on his charges?

The trial was simply never finished, but you could say he was acquitted. It’s just that the trial met a dead end at some point and was folded. What I mean is that we do not know how the situation will develop, we shall see.

These are only the first two warrants out there, after all. The prosecutor indicated clearly that those won’t be the last two, and that he will act further using the evidence he has at hand.

Uhuru Kenyatta. Photo: WPA Pool/Getty Images

Can the accused be tried in absentia by the ICC, as was in the MH17 case?

No, this isn’t possible, and that is indeed an issue. But a trial in absentia isn’t the best option anyway, and this is why the authors of the statute decided to rule this option out from the very start. No, the ICC cannot try people in absentia.

What is Putin’s status in the world now, what position is he in? Can he leave the country?

I think he can travel anywhere he wants, it’s up to him. Well, and up to the leaders of the countries that wish to welcome him and allow him to enter.

Speaking about the obligations to arrest him and turn him in to the court, only members of the ICC have such obligations.

There is also something that makes the whole situation significantly more complex: the international law provides acting leaders of countries with immunity until their powers are over. This is not going to last forever as well, though.

I wouldn’t be so sure about it.

Actually, apart from Kenyatta whom I mentioned, there were other leaders of countries that were found guilty, but they were taken to the court when they were no longer in power. There is another exception, though: Omar al-Bashir is still in Sudan and not in The Hague, although his arrest warrant is still in force. So, this creates a sort of collision: on the one hand, the state must perform certain compulsory actions, but on the other, they are precluded because of immunity. States have mutual obligations to respect the immunity of their leaders among other things.

There is an opinion, reflected in the ICC case law, and it relies upon decisions issued by other courts, including the case of Charles Taylor, the former president of Liberia, who was tried by the Special Court for Sierra Leone. The opinion is that international courts are not state organs, they act on behalf of the international community, and immunity cannot be used here.

There is also the practical side of any potential arrest and turning someone in to the court, and different states have different opinions on this. Many of them believe the immunity of a country’s leader cannot be ignored.

Of course, this will be an issue. But again, we do not know what the judges put in their decision to issue the warrants. Judging by what was done in the past, they must have somehow explained it.

I think the logic here is as follows: at this very moment, the judges have indicated what they think of the evidence provided to them by the prosecutor. How and when these warrants are going to be executed, and whether this immunity would mean anything at all: all of these are not today’s questions. When it comes to applying this in practice, we shall see.

Let’s see how it might happen. Say, Vladimir Putin arrives in…

In Dushanbe, for instance. Tajikistan is a member of the Rome Statute.

Let it be Dushanbe. What happens when he arrives there? Some kind of Tajikistan National Guard circles him and puts him in handcuffs?

Why not? I am simply telling you what potential scenarios might look like. I see, you’re being ironic here, but my suggestion with Dushanbe was intentional, too. In reality, the authorities of any country Putin visits will be deciding what to do with their international obligations of one kind or another. There was a lot of that going on with al-Bashir, by the way.

Omar al-Bashir. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

I was just about to mention al-Bashir. He travelled quite a lot even when his arrest warrant was already active.

He did not travel completely freely, but he travelled, yes, and visited the Rome Statute member countries, too.

And the ICC later ruled that those countries were not up to their Statute commitments. It was especially tough for him in South Africa where courts and local activists intervened, and the whole situation was quite tense. We may assume that something like this might happen to Putin somewhere. But we also do not see him travelling to any Rome Statute countries. If he does visit one such country, he will put the local authorities into a position where they will have to make certain decisions. Let me repeat myself: different states have different attitudes towards the immunity, and they are not very enthusiastic to ignore it.

So, from now on, every time Putin wants to go somewhere, he will have to hold a separate negotiation and discuss his own safety?

It’s hard for me to say, people who set up his trips decide such things. But I believe that there will also be some pressure upon certain states, for instance, forcing them to withdraw from the Rome Statute. The UN Security Council may freeze the ICC investigation, but this would require all permanent members to vote in favour of this, which is hardly likely these days. In any case, there are a lot of options here. The attitude towards the ICC is very different among countries, and the US, Israel, and several other countries are not quite eager to cooperate with it. Presumably, all those things will be taken into account.

The situation with Putin’s “accomplice”, commissioner for children’s rights Maria Lvova-Belova, is not that complicated, is it?

Yes, she is in a position that implies no immunity. There are three individuals that beyond doubt enjoy immunity: a head of state, a head of government, and a foreign minister. With other officials it is much easier.

If we look at the ICC decision from a symbolic POV rather than a practical or legal one, what meaning does it have?

From a symbolic POV this is a very important message. It means that the International Criminal Court relies upon the norms of law and considers it important to implement its mission. In simpler words, the court is not afraid to act against officials of a permanent UN Security Council member. From this perspective, the entire situation is unprecedented, and it marks a truly historical moment. I think this day will go down in history.

We shall see after some time what practical meaning it is going to have. There were many investigations throughout history, both international and domestic ones, that seemed completely hopeless and unrealistic, with political issues being discussed. You may remember that Radovan Karadžić, the former president of Republika Srpska, and General Ratko Mladić both participated in the peace negotiations. During his arrest, Karadžić referred to some kind of immunity, allegedly provided to him by the negotiators.

International justice is a very long-distance run, and the finish line is never in sight from the very start. But history shows that many individuals who were believed to be out of reach eventually stood trial.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]