A shootout in Kherson

On the evening of 17 June 2022, gunshots rang out in a summer cafe on the embankment of the Dnipro River in the city of Kherson. At first, it was single shots. Then, a machine gun was fired, local residents recall. A few seconds passed, and three lifeless bodies and two injured men were lying on the ground. A few minutes later, the sirens of the arriving ambulance pierced the air.

Journalists would later learn that Russian serviceman Sergey Obukhov and two employees of Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB), Igor Yakubinsky and Sergey Privalov, were killed in the shootout. Soldier Igor Sudin and lieutenant colonel of the FSB Dmitry Borodin were hospitalised and later transported to a hospital in Crimea. The only person to come out unharmed, according to the media reports, was Yevgeny Tikhonov, the son of ex-head of the FSB Special Purpose Centre Alexander Tikhonov. He was able to quickly flee the scene.

“The Russians are so bored here that they’ve started shooting each other?” Yevgeny, ex-officer of the Kherson police, expressed bewilderment talking about the incident the next morning. The news about the shootout immediately spread around the city. “Russian gunners shot Russian FSB agents! These ‘warriors’ will now be made out to be ‘heroes’…”

The Kherson cafe where the shootout occurred. Photo: social media

According to the former officer, he found out from his former colleagues who had agreed to cooperate with Russian authorities that two gunners, in uniform and armed, had been drinking at the cafe. Four FSB employees were sitting at the next table. All of them were drunk. The FSB officers at some point decided to tell the soldiers that it was unseemly to drink while wearing the uniform. In response, the soldiers reached for their guns.

“There were constant conflicts between Russian servicemen and law enforcement officers in Kherson during the occupation. Even between employees of the same agency that were from different departments. We would often hear bursts of automatic fire in the evenings,” Yevgeny explains. “But this incident surprised even us. I guess the soldiers usually had dinner at that cafe and, as Russians do, drank one or two shots of strong alcohol. The fact that the law enforcement officers began making snide comments about their uniform and weapons… Well, I don’t know… I doubt that anyone changes out of their uniform and turns in their weapons to drop by a cafe when there’s a war.”

Russian national news stayed silent about the shootout that resulted in three corpses and two injured. The names of the people involved were basically swept under the rug. But a couple of months later, the media started reporting on two of the killed men — lieutenant colonel of the FSB Sergey Privalov and sergeant Sergey Obukhov.

Privalov, according to an article published in the media of his native Kamchatka, “was killed performing military duties”. He was buried with honours at the city cemetery in Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, Kamchatka’s central city. Despite his high standing and, judging by his tombstone picture, multiple medals, his death is not mentioned on the website of the local administration, even though there are articles on other participants of the “special military operation”. There is also no information on him being awarded an Order of Courage. Since the start of the war, almost all Russian soldiers whose deaths in Ukraine were confirmed have been awarded one posthumously.

Meanwhile, gunner Obukhov was made into a hero in the news. He was buried with military honours in Crimea’s village Kostyantynivka. He was posthumously awarded an Order of Courage, while 17 June was proclaimed Obukhov’s Day by the school he went to in the village of Shileksha, where the soldier grew up.

Village Shileksha, Ivanovo region of Russia. Photo: Elena Georgieva, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta Europe

‘Old drunks died, the new ones haven’t taken their place’

“If only we had a road, there would be no problems at all,” Svetlana Korchagina, director of the Shileksha House of Artisans, says.

The locals have a point. The best way to reach the village of Shileksha, Ivanovo region of Russia, is during winter, when snow and water freeze over in the countless holes in the road, making it a bit easier to drive through. Although it does not help with the shaking anytime the car hits a bump.

But the difficult road is worth it. The second you ride into the village, you see neat houses covered in snow, a well-kept road, and an architectural monument rising above it all — a partly-destroyed building of an old Trinity Church, built in the year 1800. According to Ruslan Kurochkin, the 33-year-old head of the village, there are no plans to restore it — the damage is too great. But there is still plenty to look at.

The House of Artisans. Photo: Elena Georgieva, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta Europe

I meet with Ruslan in the House of Artisans: an incredible place. The villagers managed to preserve the traditional crafts of central Russia, making hard work their signature trait. They also teach their children traditional crafts there.

The employees of the house are always happy to have guests. Sitting at a wooden table, we eat from clay pots — a delicious stew that was just taken out from a wood stove by Svetlana, who also works at the house. A Russian samovar puffs out smoke on the table.

The current population of Shileksha is about 400 people. According to Svetlana, life was busier here ten years ago. Young people stayed in the village back then, now almost all of them leave. They do not want to live in a village, as if they have forgotten how to work.

“They go to Moscow, because they see the financial prospects,” Svetlana explains. “For example, here people are ready to work for 12,000 rubles (€156) [per month]; in Moscow, no one will leave their house for this money — everyone knows how to count it. If they don’t go to Moscow, they at least leave for Ivanovo [the regional capital — translator’s note]. Everyone wants to go to a place with prospects. If parents buy a flat for their child, they try to buy one in the city.”

Village Shileksha, the Trinity Church. Photo: Elena Georgieva, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta Europe

There are a lot of problems in Shileksha, just like everywhere else, but it looks a bit different from an average Russian village — there are no rickety fences and hopelessly-grey houses.

“They say that villages are dying out and the first ones to go are the drunks,” Svetlana says before we part ways. “Before, we had a lot of drunks, you could ask one to chop wood in exchange for a bottle. But now we only have one or two men in the entire village that would agree to help for a bottle. And that’s it, there are very few drunks left. They do not make it to old age, as you know. Old drunks died, the new ones haven’t taken their place. Maybe they go to the city and drink themselves to death there?.. But in our village, there are certainly not many left.”

‘They wouldn’t just give him an Order of Courage for nothing’

A Russian flag is hoisted near the entry to Shileksha’s school. Another one hangs on the building itself. The wooden school is covered in white snow that glistens in the sun, an image straight from a postcard.

However, a black plaque hangs to the right of the entry. It has a picture of 28-year-old sergeant Sergey Obukhov, the school’s graduate, on it.

Photo of Sergey Obukhov. Part of an exhibit in the Shileksha school museum. Photo: Elena Georgieva, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta Europe

The door to the school is closed: only the students and the staff are allowed inside. There is a PE class held on the school grounds, with four kids aged about 10 skiing on a fresh track.

A PE lesson at the Shileksha school. Photo: Elena Georgieva, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta Europe

While kids are in class, the photographer and I wait for recess so as not to disrupt the lessons. We look around. Not far from the school there is a memorial to the residents of Shileksha killed in WWII and after the war. The village appears to be small, but there are a lot of names. It is clear that they are serious about preserving the memory of war heroes here.

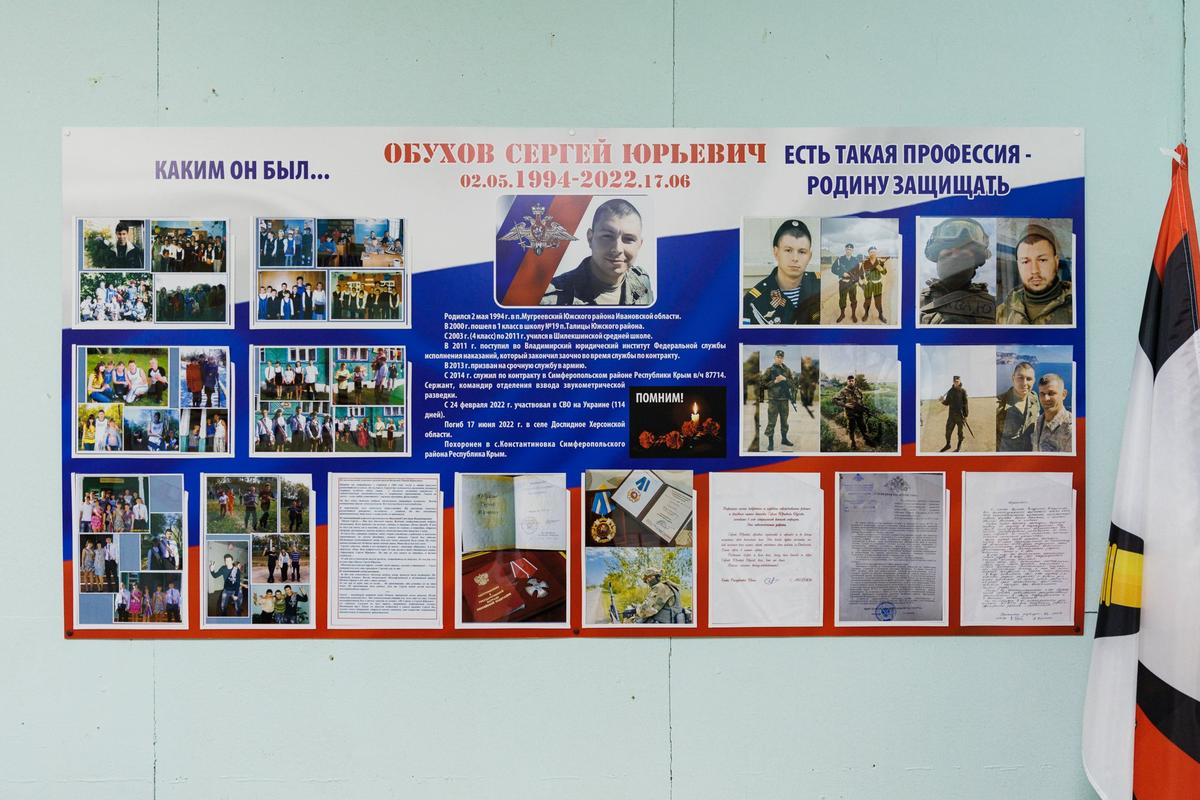

Natalia Semyonova, the school principal, is surprised by the unexpected guests’ arrival, but agrees to show us the little installation dedicated to Obukhov’s memory. A stand with photos and main facts about Sergey Obukhov was put up in a small room. Below there is a table with Sergey’s portrait. On the right from the table there is an artillery troops flag.

Natalia Semyonova, the school principal. Photo: Elena Georgieva, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta Europe

“Sergey was killed in June,” Natalia says. “On my initiative, we began gathering information about him in September. His wife sent us some stuff, the school team interviewed his teachers and classmates. Here are the photos from his school and army days.”

On 10 June 2022, Sergey Obukhov was awarded an Order for Loyalty to Duty. On 5 July, he received an Order of Courage, posthumously. The memorial plaque on the school building was unveiled on 9 December.

According to the principal, Sergey was a good boy, he was interested in computers. He didn’t get good grades, but he was the heart of the class — the funny kid. Girls loved him a lot. He always treated everyone well. Took part in many extracurricular activities, was a class leader.

“Our students got in touch with his classmates, they all left the village, so the students read out the classmates’ memories [at the unveiling],” Natalia continues. “We invited his mother, step-father, step-sister, the head of the administration. The residents of the village came, too, as did Sergey’s ex-colleagues from the local prison. He worked there while he was studying at the Federal Penitentiary Service Law Institute in [the city of] Vladimir. The kids learnt facts about Sergey’s biography during the event. This is patriotic education. One of his former teachers could not deliver her speech, she kept crying.”

The principal has, of course, heard about what is written in the media and social networks about the circumstances of Sergey’s death. But she has not found “confirmed reports of him dying in a shootout in a Kherson cafe”.

“We filed an inquiry with the draft office. We received a reply stating that Sergey was killed in [the village of] Doslidne, Kherson region,” Natalia explains. “They sent us a commander’s letter [honouring Sergey]. If you look into it, they wouldn’t just give him an Order of Courage for nothing. If this story [involves] high-ranking men… Then I won’t be able to learn the truth, how could you get to the truth here?..”

The gym in the Shileksha school. Photo: Elena Georgieva, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta Europe

‘It’s a pity, of course, about the boy’

There are a lot of items in the school museum, they do not fit in one room. In general, they are dedicated to WWII veterans, the most treasured pieces being their letters from the front. There are stands about the Afghan War, they are put up in the corridors. Men from Shileksha went to many wars, it seems.

“Three men from the village got mobilised, but they’re on the older side,” the principal says, referring to the latest events. “Mostly those who previously did contract service. I think there were no volunteers. There are three draftees. I think that should be enough. I hope there won’t be any more of them.”

In the room next to the school museum, one can see antique items, many of them are over 100 years old.

The Shileksha school. Photo: Elena Georgieva, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta Europe

“We try to get kids into history so they know our heroes,” Natalia says. “The students collect information on their grandfathers and great-grandfathers so they themselves take an interest in their family history and learn more about it.”

That morning the students were shovelling the snow at the houses of veterans — the home front workers during WWII — and those who live alone, without any help. The school is big on volunteer work. It is also in possession of a hectare of land, used to grow vegetables. The canteen employees use the vegetables in their cooking. So, even if the road to the village gets lost in the snow, the people here will still get by.

During our goodbyes, the principal says sadly: “It’s a pity, of course, about the boy. He was a good one. And his young wife is a widow now. His six-year-old son has been left without a father.”

Village Shileksha, the central street. Photo: Elena Georgieva, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta Europe

‘What happens if everyone raises their hands…’

Alexander Kruglyakov is Sergey’s step-father, he raised him from when Sergey was 11 years old. Alexander is an ex-employee of the Federal Penitentiary Service. He is retired, but he can’t sit idle at home doing nothing. He now works as a cooper in the House of Artisans. He makes wooden containers and teaches children cooperage.

“We started getting along quickly,” Alexander recalls. “He was a curious boy, loved animals. Of course, he helped around the house, that’s normal in villages, you can’t afford to be lazy here.”

Alexander Kruglyakov, Sergey’s step-father, talks about him in the House of Artisans. Photo: Elena Georgieva, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta Europe

Alexander smiles as he recalls how the two of them would go camping sometimes, while his youngest daughter Natasha was still too small. Once the daughter got older, they went on camping trips together as a family. They would go to the river with a tent for a few days. They relaxed, went fishing, and cooked on a bonfire.

In 2013, Sergey went off to do the mandatory army service. By the end of his term, Sergey signed a contract and continued serving in the Moscow region.

“When Crimea became part of Russia in 2014, they were recruiting young officers willing to serve on the peninsula, and my son was on his way there on one of the first flights,” Alexander says. “He just called me from the airfield and stated that it was a done deal. I think he wanted to be more independent, although by that point he made a lot of decisions by himself.”

In Crimea, Sergey married a local woman. They lived in a private area on the outskirts of Simferopol. According to his step-father, Sergey loved Crimea, he wanted to stay there. He had a lot of plans. He wanted to build a house and have at least two kids.

Alexander does not know how much Sergey made, but it was at least 40,000 rubles (€520) per month. One could earn the same in the village, if they worked at the prison. But Alexander says that his son liked the army, it was his calling.

“We learnt that he had started taking part in the special operation at the end of February, and we were very anxious,” Alexander admits. “But it’s his duty. I myself am retired after 20 years of service. I understand what it’s like. What happens if everyone raises their hands and says that they don’t want to get involved?.. Especially those in uniform, their work is directly related to fulfilling their duty.”

They were concerned about Sergey, but no bad news arrived from there. Even if there had been bad news, Sergey would not have told them. He called them once every week or two. More often, he would share news through his wife, she called his parents. He would say that he was alive and well, everything was OK. He did not talk about anything else.

The penal settlement where Sergey’s mother and step-father worked. Photo: Elena Georgieva, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta Europe

‘There has to be a reason why we need these Ukrainian lands’

The news of Sergey’s death reached them on 18 June 2022. At first, the parents did not believe it, until they received a phone call from the military unit where Sergey served. They packed at once and went to Rostov-on-Don by car, where the identification of the body would take place. But the unit’s commander identified the body before they reached the city. The Defence Ministry helped to pay for the funeral.

Part of the memorial for Sergey Obukhov at the Shileksha school. Photo: Elena Georgieva, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta Europe

“But they can’t pay for everything,” Alexander says. “So, you want to install a monument, for example. You know how much Karelian marble or something like that costs. It’s not cheap, to put it lightly.

The ministry can’t be paying for, let’s say, a 300,000 rubles (€3,900) monument, there must be some limit,” Sergey’s step-father adds, worrying about the state treasury.

“Sergey Obukhov was killed in the village Doslidne, located 30 km away from Kherson,” the official website of the Ivanovo region town Kineshma states. Furthermore, Sergey’s name was added to the Ivanovo region memory book: “He showcased courage and bravery in combat. Sacrificing his life, he saved fellow soldiers who were able to escape the encirclement thanks to his heroic deed.”

Village Shileksha. Photo: Elena Georgieva, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta Europe

The files, sent to the Shileksha school from the military unit in Crimea where Sergey served, state that contract serviceman Obukhov took part in the “special military operation” from 24 February 2022.

Nothing clear is written down about the circumstances of his death. Neither could his step-father tell us how he died. He just muddled his way through a retelling of the official letter, adding that the wife of the injured soldier saved by Sergey came to see Sergey’s wife and thank her.

Alexander’s eyes are full of sadness. Speaking of his son, he sometimes smiles, but it looks melancholy. Talking about his son’s life, from childhood until his last days, he never refers to him by his name.

“Is there an understanding of what all of this is for?” my interlocutor reflects. “Before, we also heard sporadically through news that Donbas was being bombed, people were being shot. But now it has impacted everyone directly. What impact? Our [government] started the special operation for some important reason, there has to be a reason why we need these Ukrainian lands…”

It has been eight months since Sergey’s death. His mother and step-father still can’t believe he’s gone, it seems.

“We have his picture at home, sometimes I talk to him, tell him hello in the morning,” Alexander admits. “He became my real son, all of this hurts me very much. It hurts to look at my wife… And we still have to somehow continue living.”

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]