Oil, like other fossil resources, often causes violence and wars. In 2003, the US started a war in Iraq, according to some, seeking to gain control of the oil fields. Twenty years later, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, financing it with money from oil and gas exports.

Much has changed in the past year. European countries have virtually refused to buy oil and gas from Russia and have urgently started looking for alternatives. This is a good chance not only to stop financing aggressive petrostates, but also to limit the irreparable damage to the environment caused by burning fossil fuels.

But will the world face a full-fledged energy transition — or will we simply replace some hydrocarbons with others? And is it a good time to think about a “green economy” while a war is going on? That’s what we discussed with Naomi Klein, Professor of Climate Justice at the University of British Columbia and author of ‘This Changes Everything’ and ‘The Shock Doctrine’.

Naomi Klein

Writer

Professor of Climate Justice at the University of British Columbia

Many experts believe that the 1990s radical market reforms in Russia were one of the reasons why the country eventually turned into a dictatorship — they were too painful and misguided and partially because of them people were disappointed in democracy. Last year, Russia launched a full-scale war with Ukraine. To what extent is “shock therapy” to blame for what’s going on right now?

I think it has a huge amount to do with it. It’s very clear that there was no desire in Washington for Gorbachev’s vision of the Soviet Union. He talked about a Third Way and the Scandinavian social democratic model. But there was this bunch of cold warriors in Washington who wanted Russia to pay. They didn’t want Russia to be strong, they were still in a Cold War mentality. But also, we know that the “Wild West capitalism” was what created the oligarchs. They, in turn, absolutely backed Yeltsin, without whom we would not have Putin. The history of “shock therapy” is inextricable from the fact that civil society never stood a chance in Russia.

As North Americans, we have a terrible tendency to make ourselves the star of every story, for better or worse. We’re either the hero or the villain, but we’re never just a part of the story. So there is a danger of telling this story in a way where the US is the only relevant actor and I don’t think that’s true.

But I do think that Washington’s policies and its duplicity in this period helped put Russia on the front of a very, very dangerous and damaging path.

Russians were led to believe that there would be an aid package in exchange for these brutal economic policies but it didn’t come.

But it wasn’t the only factor, of course. As to what’s happening with Ukraine right now, I’ve been really distressed to see Zelensky kind of getting into bed with BlackRock, JP Morgan, going to American businesses and saying “Here, take my country, rebuild it”. We’ve seen this before and this is what’s called “shock therapy” or “disaster capitalism”.

A video conference president of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelenskyy with Larry Fink, CEO of one of the world's leading investment managers, BlackRock. Photo by President of Ukraine website

Ever since the US invaded Iraq, it redefined this playbook of treating post-war reconstruction as a private business opportunity and not as a duty to build a sturdy, self-sufficient economy, which was the ethos after the Second World War. The only alternative to that is Russia paying reparations. So there’s either going to be justice or there’s going to be injustice. And the injustice takes the forms of these inequitable economic policies that are going to lead to backlash of various kinds.

In one of your essays, you wrote that “bombs follow oil” speaking about the war in Iraq. It seems like today the pattern repeats itself in a slightly different way — bombs that were created using oil money are now exploding in Ukraine. Are natural resources, violence, and conflict that interconnected?

Of course they’re profoundly interconnected. Wars have always been fought to seize the wealth of the land. Wars have also been fought for fossil fuels: to control the extraction and the transportation through pipelines. It really is the story of warfare in the modern age.

We are very deep in this cycle. Oil is underwriting the war machines, frankly, on both sides in Ukraine. Obviously, Russia is a petrostate and its number one export is fossil fuels. There’s a vicious cycle with war and petrostates because any conflict drives up the price of oil, and so it becomes more profitable to export it. So, even other forms of economic sanctions are much less effective when the price of your primary export is soaring because of the war.

That’s what’s been happening with Russia. But what’s also important to remember is that when the US sends weapons to Ukraine, it does so using the infrastructure that has been underwritten by oil wars for many decades now.

You’ve said multiple times that extracting fossil fuels is immoral because it’s harmful to the environment. Does it matter whether we’re purchasing oil from Putin, Maduro or someone else?

All of our economies are underwritten with substances that are destabilising life on Earth. Whether we’re petrostates or we’re petroclients, I don’t think that that’s a particularly meaningful distinction. There’s no doubt that fossil fuels spark economic interests, be that state interests or private interests, and often the two are so intertwined that it’s pretty difficult to pry them apart. These forces are driving policies that have been very effective barriers to good intentions, to various attempts to get off fossil fuels. They doggedly stood in the way.

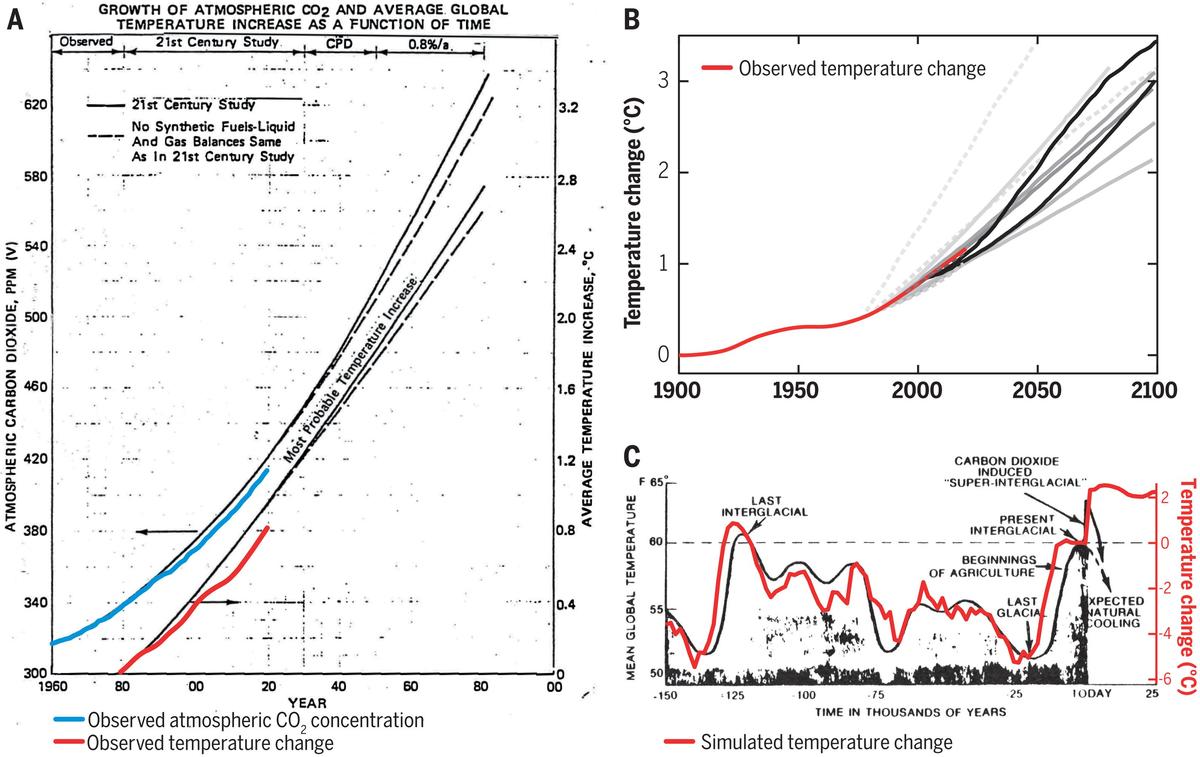

There’s a particular responsibility that rests with those forces, and we learn more and more about it every day, for instance in terms of obstruction that a company like Exxon has engaged in. The research that they themselves did dating back to the 1970s and then the misinformation that they spread and the interference in policy debates. I don’t think that we’re all equally guilty just because some of us buy oil and some of us dig it up. But I do think that it’s profoundly immoral and all the parties involved are responsible.

Historically observed temperature change (red) and atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration (blue) over time, compared against global warming projections reported by ExxonMobil scientists. Photo by Scince

The study that you mention claims that ExxonMobile have been building climate change models since the 1970s, and those turned out to be quite accurate. But then they stopped researching this field and chose to use the money for lobbying for fossil fuels extraction. What does this case tell us? Have we had all the knowledge we need about global warming for decades and have done nothing with it?

To be clear, what we’re getting [from this study] is more details. We already knew the broad structures of this. We have copies of reports that were sent to the Johnson (Lyndon B. Johnson was the president of the US from 1963 to 1969 — editor’s note) administration about the fact that scientists knew that fossil fuels were going to lead to significant and dangerous warming.

As to why “we” ignored it, firstly who is “we”? There were many attempts to respond, we have had various international gatherings. If you think about the Rio Earth Summit and the momentum that came out of it which led to the creation of the Triple-C (initiative that collects data on various climate change related projects within the EU — editor’s note), there is also IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a UN body — editor’s note) and so on. There have been so many attempts but those attempts have been blocked, sabotaged and interfered with.

Поддержать независимую журналистику

It’s really important to not just use words like “we”: “we didn’t act” and “why didn’t we do this” — it’s really a recipe for hopelessness and defeatism. Because if “we” knew and “we” decided not to act all these years and then why would that change?

It’s the question of money in politics, certainly in the United States and in my own country, Canada. You’ll have elections where politicians will promise to take climate change seriously and then they get elected on those promises and roll back. This research shows all the lobbying trails, very aggressive efforts to undercut climate action.

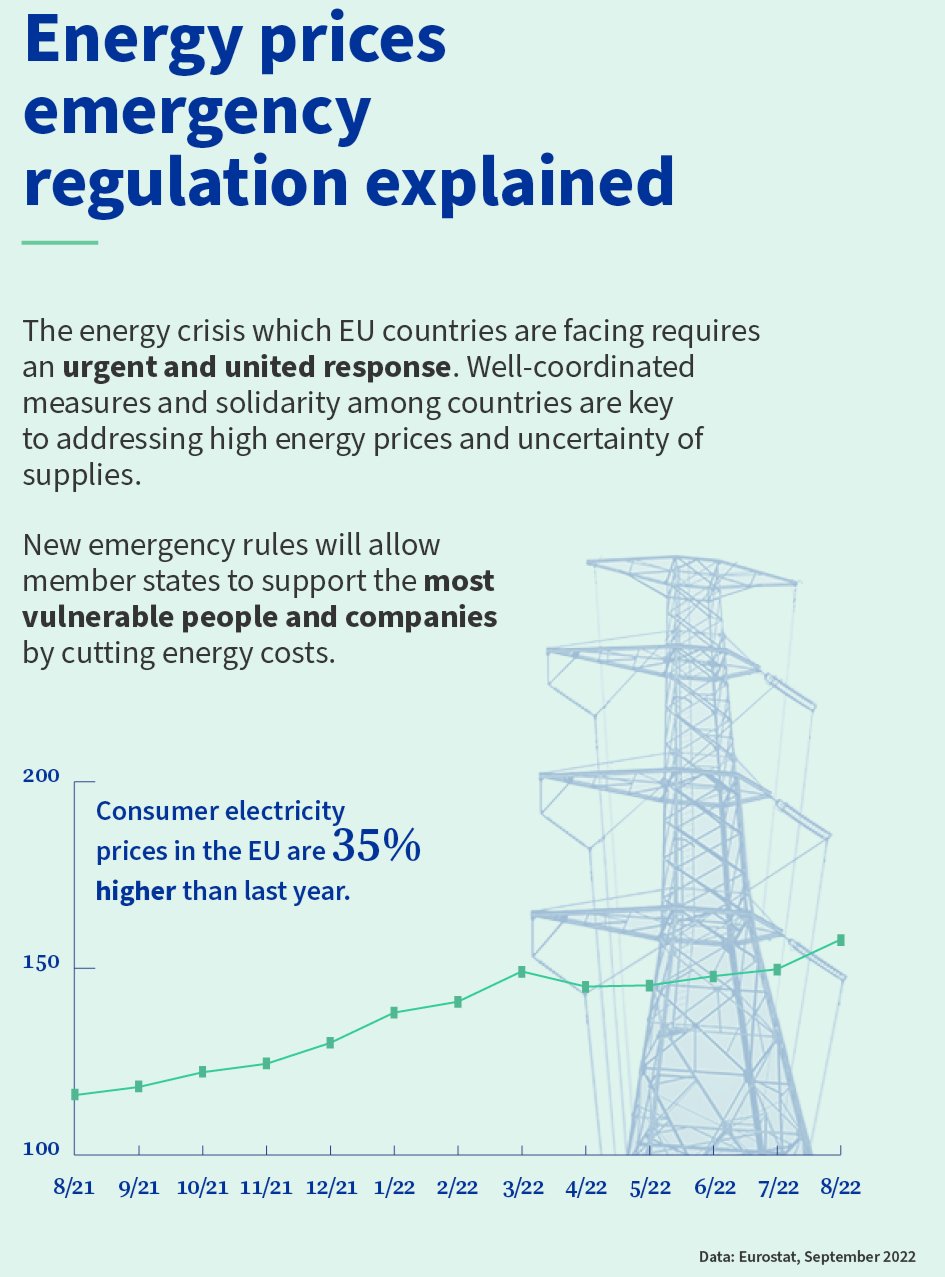

Another thing that has happened repeatedly is that you’ll have some impulse towards action and then there will be a crisis that is harnessed by fossil fuel interests, which lets some argue: “Well, we now can’t afford to act on climate.” We saw a lot of this after the 2008 financial crisis, when Europe was ready to roll out renewable energy. A lot of European countries were getting serious about that transition and then were kind of blasted back by the financial crisis. The governments started saying: “If we have to choose between putting food on the table and acting on climate, obviously we’re going to put food on the table.”

This, however, really was a false dichotomy because the whole point of having a serious green industrial policy or a global Green New Deal (set of policies, primarily in developed countries, aimed at addressing climate change — editor’s note) is that it is a plan to create jobs, and transform the economy to a system that is meeting people’s needs much better than our current system, which is wildly unequal, unfair and is forcing people into situations where they’re living such economically precarious lives that any marginal change in the price of energy is impossible to hold.

We saw that after the financial crisis in 2008, and now we’re seeing it around inflation and the war in Ukraine. Once again we’re being told that climate action is a luxury good.

That’s a failure of policy. It is absolutely possible to design climate policies that put the burden of the costs on the polluters who not only caused the crisis, but actively obstructed every attempt [to overcome it] for many decades. We have COP-27 (UN Climate Change Conference — editor’s note) which means governments have been meeting for 27 years, (actually 28 because they missed one) to talk about lowering fossil fuels use but we’re still going in the opposite direction. And the next COP is going to be led by a former fossil fuel executive.

So if anything, fossil fuel companies are getting more power in these negotiations, not less. As a result what we have is governments’ unwillingness to go after the large players and get them to pay for the green transition. Instead we have policies that ask working people, unemployed people, to accept higher petrol and heating costs. Of course, there’s going to be a backlash, right?

So if we think about the situation we’re in right now with Ukraine, but also the fact that other repressive regimes are profiting off of Russia’s aggression, what is the best way to reduce the power of a petrostate, whether it is Russia or Saudi Arabia? It is for the rest of us to get off fossil fuels as quickly as we can. And the only way that’s going to happen is if we design policies that are actually fair for working people. That is going to require for the forces that got us into this mess, which are oil companies and petrostates, to actually foot the bill for this transition.

In order not to rely on Russia for fossil fuels, many Western countries might either invest into greener renewable sources of energy or look to purchase fossil fuels elsewhere. They are also increasing their military spending which requires a lot of resources. Do these factors make the green transition more or less likely?

We’re in a very bizarre moment where we’re seeing evidence for both scenarios. Certainly European countries are spending more on their military than they have in many years. But we’re also seeing an acceleration of some green investments, of transition to renewables.

Germany is an interesting case for that. It is both accelerating its renewable transition, increasing coal extraction and building new LNG (liquefied natural gas — editor’s note) terminals, which is locking them in to continue their LNG reliance, and they’re spending more on military.

Russian and Western politicians visit the Sakhalin-II project on 18 February 2009. Photo by Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0

Obviously, there’s going to be a stop gap — no energy transition takes place overnight. In the earliest days of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the US and Canadian energy companies immediately came out and started saying things like “This is why we have to drill everywhere all the time, any pipeline that you’ve ever stopped, we need to approve it now, because we are going to fix Europe’s energy crisis.”

That’s a fantasy, because that requires building infrastructure as well. It’s also going to take time. So it’s a question of where our investments are going to be. In my opinion, they should not be in the infrastructure that is torturing the planet and is bankrolling all of these nefarious players around the world, in Russia, in Saudi Arabia, but also in the United States.

Our possibilities are, to a large extent, shaped by the price of fossil fuels. Whenever there is instability in an oil rich region, the markets panic and the price goes up. Now with Putin’s war, the industry is bound and determined to dig it up while the price is high.

There is a flip side to that though, which is consumers. From a producer’s perspective, when the price is high, you want to dig it up. But from a consumer’s perspective, when the price is high, you want an electric vehicle, you want a heat pump, and you want to consume less because it costs more, right? I think we have a very small window of time to work with the consumers and their realisation that they might not want to be on this rollercoaster anymore.

At a certain point, choices have to be made. This is the thing about climate change — you actually have to make some hard choices, including consuming less.

This is the part of the climate discussion that you’re never allowed to talk about, at least in North America.

But climate disruption is intimately connected to wealth and overconsumption. It is overwhelmingly the wealthiest 10% that is responsible for this crisis.

We, overconsumers, have to not just be talking about how to replace our fossil fuel vehicles with electric ones. We have to be talking about consuming less energy overall because there’s no such thing as a perfectly green, clean technology. Everything requires extraction. Everything comes at a cost, including lithium for the batteries.

So if we don’t want to repeat the exact same patterns about military conflict and environmental depletion, but only in the name of green technologies, we have to be talking about consuming less. We need major investments in public transit, in electrified public transit, as opposed to everybody supposedly being able to get their private electric car. At the same time it is crucial to recycle the resources that we use, including metal and batteries. We’re still in this fantasy of being able to deplete and consume endlessly, just moving from one input to another.

Source: European Council

Restrictions on Russia’s energy sector resulted in high prices for gas and electricity in Europe. Many governments were urging people to save energy. Do you think this could help?

When I mention consuming less, it’s not an individual lifestyle issue, I’m talking about overconsumers. What creates backlash is when the elites are able to do whatever they want, continue flying around in private planes. And then people who are living very economically precarious lives are told: “Well, the solution is for you to turn down the heat or put on a sweater.” This is the great rule of living in a capitalist society — you’re really not ever supposed to talk about consuming less.

But, for example, during the Second World War, citizens in Canada, the US and Britain reduced their consumption dramatically, including their consumption of energy. It’s really interesting to look at how they pulled this off. At the high point during the Second World War, Americans were getting 40% of their produce from the gardens that were planted in their backyards. Public transit use in Canada went up by around 85% because people were conserving oil and there was a ban on leisure driving, almost like during COVID.

What’s really interesting about how they were able to do this is that they stressed the fairness of these measures. Even Hollywood celebrities and large corporations had to follow the same rules. And that was the only reason why people accepted them.

Nowadays it’s almost unthinkable to expect the ‘Davos class’ to have to follow the same rules as everyone else. So long as that’s true, of course, people should not accept the idea that they have to solve the climate crisis themselves.

This is why people latch onto it. We saw this with Macron when he introduced carbon pricing and it inspired the yellow vest movement. Unjust climate policies will lead to backlash. But that doesn’t mean that every climate policy has to be unjust. And that is the whole idea behind policies like the Green New Deal, which merge the need for a much fairer economy, the need for better unionised jobs that are going to meet people’s needs and the urge to lower emissions radically and on a very tight timeline.

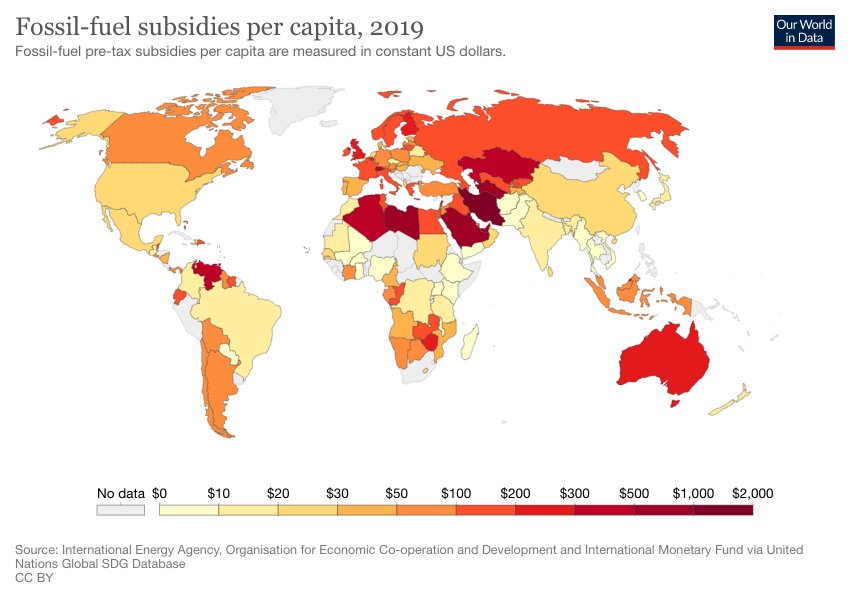

Fossil-fuel subsidies per capita, 2019. Photo by Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0

Are there countries whose policies regarding climate are something that one should look up to? Countries that overcame the “extractivist mindset”?

There’s some exciting things happening in Latin America right now. Colombia’s new government is really taking the leadership role on moving away from fossil fuel extraction, which is tremendously brave for a country with very high levels of poverty.

There were moments like this before, when Ecuador elected a leftist government and wanted to go back to the project of leaving oil underground in the Yasuni rainforest, but came to international climate negotiations and said “We want to do this, but we don’t believe we should have to pay the full cost.” And it is fair, right? Because we all benefit from oil staying underground. That’s a basic principle of justice. And the international community didn’t step up at that time. And eventually the pressures for extraction won out in Ecuador.

There’s this new batch of left governments in Latin America: in Chile, in Brazil, in Colombia and elsewhere. If we want these governments to leave fossil fuels in the ground, then countries that have been emitting carbon for a couple hundred years and have the historical responsibility when it comes to climate change, have to pay into these kinds of funds that like they said they would but have been completely recalcitrant. This principle of reparations is one that we have to take seriously. When it comes to climate and when it comes to war.

Climate justice is not a luxury. If we don’t do this in a fair way, it won’t be done at all.

The West hasn’t succeeded in helping Ukraine to end the war yet. However, major world powers were able to respond with military support. They were also ready to suffer serious economic damage by breaking up ties with Russia (e.g. almost stopping oil and gas trade and withdrawing assets from Russia). Does it give you any hope that such cooperation is possible on a global scale — as a response to the climate crisis? Will this war be a lesson for the world on how to deal with future disasters?

There has been such a rapid response to Russia’s invasion that it shakes off the biggest barrier to our ability to respond to public crises, including climate change. After I published ‘This Changes Everything’ in 2014 I heard things like: “Oh, we don’t need to do that much; We can just have a carbon tax, right?” But now everybody's starting to understand that it’s going to take a paradigm shift. It’s going to take a transformation of what our economies are for — not for growth, but for meeting people’s needs, for quality of life. People believe that it cannot be done.

But when we see change on a rapid scale, when governments are breaking their own rules — like standing up to billionaires, even if they’re only Russian oligarchs — it shakes off the sense of impossibility. We grew up in the neoliberal era and most of us can’t remember the way people mobilised during the Second World War and transformed their lives to support the war effort. Our memories are only of governments unmaking and undoing, locking in trade deals that tied their own hands and prevented them from being able to do things quickly.

So when we see swift action, whether in the face of COVID or in the face of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it is positive because it tells us we were lied to. It tells us that it is possible to act swiftly. There are still incredible double standards in when our governments decide to be outraged. Why Ukraine and not Palestine? Why democracy there and not in Saudi Arabia or Egypt? It is the double standards that are killing us now.

What we need are international movements and coalitions that are rooted in principle: if we believe in democracy, we believe in it everywhere. If we are against foreign invasions and occupations, we’re against them everywhere. If we believe that if you break a country, you have to pay for the reconstruction. We have to believe in it everywhere — in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Ukraine.

Делайте «Новую» вместе с нами!

В России введена военная цензура. Независимая журналистика под запретом. В этих условиях делать расследования из России и о России становится не просто сложнее, но и опаснее. Но мы продолжаем работу, потому что знаем, что наши читатели остаются свободными людьми. «Новая газета Европа» отчитывается только перед вами и зависит только от вас. Помогите нам оставаться антидотом от диктатуры — поддержите нас деньгами.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]