Alexander Druzhinin was set to be released from prison in eight years at the minimum. He was deceived by the state before and did not believe he would have his term reduced after going to Ukraine for a few months. “I’ll go and take a walk in the fresh air. I’m sort of used to this kind of thing anyway...” he told his wife.

The former hitman did not clarify what he is “used to” exactly, neither to his wife nor his cellmates. He used to say in court almost with pride, however, that he was a hitman and that his job was “contract killing”.

Igor Makarov (his name has been changed, but Novaya-Europe knows the real one), a detective with the police’s organised crime unit, had an almost friendly relationship with Druzhinin. He told Novaya-Europe that the hitman treated his contracts as “business only”: just like any other job.

“I was on his case for almost five years, starting from his arrest and until his last trial,” Makarov says. “It was beyond my understanding at first that murders can be treated so dispassionately. Like mowing grass or something. And he would simply shrug his shoulders and say: ‘That’s how it was back then: kill or be killed. I was just an executioner: it used to be a well-respected job some hundred years ago”.

From an athlete to a thief

Druzhinin was born in 1964 in Kirovsk, Russia’s Murmansk region. Sasha Druzhinin used to be a skier from an early age: his hometown Kirovsk is located in the Khibiny Mountains and has great skiing tracks that used to welcome skiers for training not only from all around the Soviet Union, but also from abroad back in the day.

Druzhinin was drafted into the Soviet army in the early 1980s, where he served in a unit for seasoned athletes. He completed his military service in 1984, tried to go back to professional sports, and even participated in some international competitions. However, his performances were below average, which forced Druzhinin to retire from skiing. Nevertheless, his passport with a European visa remained valid for many years.

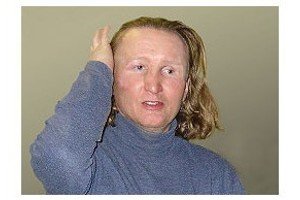

Alexander Druzhinin

“Druzhinin told me that he used to be a part of a gang that was doing thefts and robberies all across Europe in the late 1980s and early 1990s,” Igor Makarov told Novaya-Europe. “There was no Schengen agreement at that time (it was introduced in 7 countries in 1995), but the European borders used to be pretty transparent back then anyway. So, mobs used to tour Europe back and forth.

They were not afraid of prison as they knew Europe was like a holiday resort for them. They did not kill anyone, though. If Europol was a thing back then, using an integrated database, they would have been caught pretty soon.

But cooperation between police agencies of different countries left much to be desired at the time. That is why Druzhinin and his henchmen remained free for a long time. Most of the gang members were identified, though, and simply deported to Russia.”

First blood

Having returned to Russia, Druzhinin opted not to go back to Kirovsk but settled in St. Petersburg instead.

His sports connections helped him join a racketeering gang led by Vyacheslav Serikov (killed by five Makarov pistol bullets on 2 October 2005, the assassination still remains unsolved).

This organised crime group led by Serikov, a former student of the MSU Faculty of Journalism, was a part of the so-called “Malyshev’s criminal network”, called after Alexander Malyshev, who used to bear the title of “St. Petersburg’s criminal emperor” in the early 1990s. They collected tribute from businessmen in the St. Petersburg port, namely the Baltic Marine Engineering Plant.

The Baltic Marine Engineering Plant. Photo: Wikimapia

Igor Trofimov, a businessman who was trying to get rid of the gang’s patronage after Malyshev left the country, was shot dead by two hitmen wearing masks and using AKs on 11 November 1997. One of the hitmen, the investigation believes, was Alexander Druzhinin.

“He didn’t say it directly, and the court acquitted him on this charge, but from his hints I understood that Druzhik [Druzhinin’s nickname] indeed was involved in that case,” Makarov believes. “He also said that this wasn’t his first murder. He first killed a person a year before that.”

Druzhinin visited Kirovsk with a friend of his in 1996 to meet his parents, former classmates and fellow athletes. They went to a local casino where they had an argument with the local mob. The locals beat Druzhinin and his friend half to death.

After spending several weeks in a hospital, the two decided they would not return to St. Petersburg defeated: they would have lost all their respect that way. Having checked out of the hospital, they got their hands on some firearms and started a shootout right in front of the casino, killing two mobsters, including the leader of the local gang. Druzhinin and his friend were unhurt but left town right away.

A couple of weeks later, Druzhinin was summoned by Konstantin “Mogila” Yakovlev, the leader of a criminal network that Druzhinin had joined as part of the Serikov gang earlier. This happened because mobsters from Murmansk came to St. Petersburg and tried to hold the two responsible for the Kirovsk shootout.

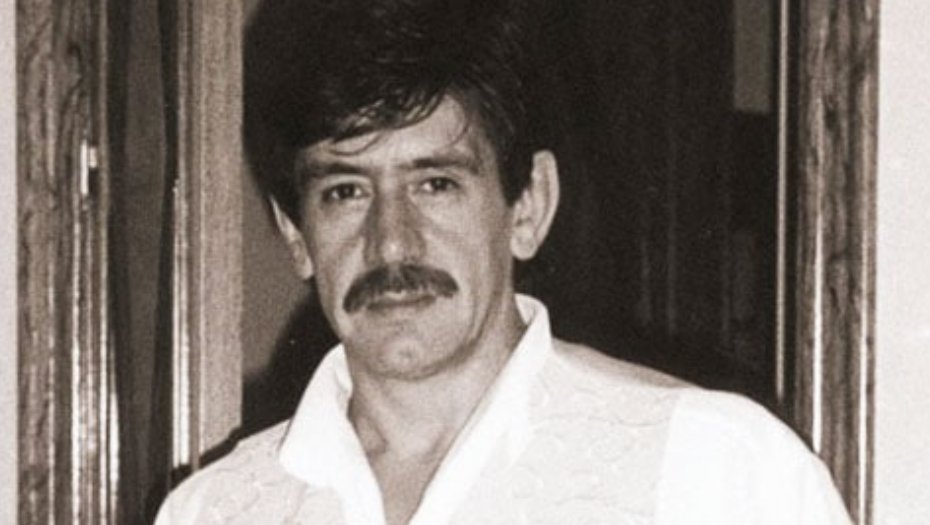

Konstantin “Mogila” Yakovlev

Yakovlev listened to both sides and concluded that his men were beaten up in Kirovsk and took revenge on their attackers, which was fine in terms of the gang “rulebook” back then.

The visitors had to return to Murmansk none the wiser, and Druzhinin was noted by Vladimir Kulibaba, the Yakovlev’s right-hand man who was in charge the gang’s muscle.

Arrested and acquitted

Serikov’s gang was arrested in 1999 after a failed assassination attempt on Vyacheslav Ivanov who used to be the gang’s member for a long time but decided to quit after Trofimov’s assassination. At least that was what he told the police. Ivanov was suspected of many crimes the gang committed earlier.

The first attempt to assassinate him happened om 7 September 1998 when he was returning home from Turkey with his common-law wife. While on the way from the airport, Ivanov’s car was chased by a motorbike. According to the investigation, the motorbike was ridden by Druzhinin, who used a Škorpion machine pistol to shoot a round against Ivanov’s vehicle. The attack left Ivanov unhurt and forced him to beef up security measures.

The next assassination attempt occurred in almost a year’s time, on 5 August 1999. Serikov’s gang attacked Ivanov in Moscow and shot up his car again using a machine gun, but Ivanov managed to jump out of the car and tumble down the side of the road. He recognised Druzhinin in one of the attackers and realised that Serikov would not leave him in peace, so he went to the police, where he shared a lot of details about the gang.

Serikov, Druzhinin, and two more gang members were arrested, and another two mobsters signed a pledge not to leave town. They were accused with assassinating Trofimov and attempting to assassinate Ivanov; the prosecutor demanded that Serikov be sentenced to 15 years in prison and Druzhinin to 20 years. However, the St. Petersburg City Court found the accused not guilty, believing that Ivanov had simply slandered them.

After Serikov was killed, his gang ceased to exist. Speaking in sports terms, Druzhinin started offering his services as a free agent. However, he was closely associated with Yakovlev’s crime network anyway. This is where he got another contract to kill, which turned out to be the turning point of his criminal career.

Caught in the act

Vadim Chechel, the CEO of Kaskad, a security company, was assassinated on 24 April 2008. The investigation found out that Chechel left the apartment he shared with his fiancée Maria Stroganova and her son and got into his car. At this moment, a man approached him and knocked on his car’s window with an envelope. Chechel rolled down the window, and a silenced gun was pressed against his head.

The hitman pulled the trigger a few times and started walking towards the roadway without dropping his weapon. It was revealed later that he planned to get into a getaway car, although he did not make it.

Some individual witnessed the whole thing and started running after the assassin. As the latter was passing by a road police vehicle, the witness shouted to the officers that the man in front of them was an armed criminal. They did just the right thing and wrestled the assassin down to the ground; a silenced pistol fell out of his pocket.

Vadim Chechel and Maria Stroganova in London

The hitman’s identity was verified in no time: it was Alexander Druzhinin, wanted nationwide for murder since 2003. Having been caught in the act, the hitman did not use the Article 51 of the Constitution that allows people not to testify against themselves, but rather stated he was ready to name his contractor. The person he claimed to be his paymaster was Denis Volchek, an MP (a business partner and friend of Konstantin Yakovlev’s, a State Duma MP from the Liberal Democratic Party, currently under investigation for fraud).

However, this legend was not confirmed. After two and a half years, Druzhinin changed his testimony and said the paymaster was Vladimir Kulibaba.

“Druzhik could have told the police he killed Chechel with personal motives, not mentioning any contractor,” Makarov says, “This way he would have been sentenced to eight years and could have been released on parole after five years in prison. Obviously, we knew he had killed at least ten more people before, but we had no real evidence to prove this. However, Druzhik was really desperate to take revenge on Kulibaba and his sidekick, driver Nikolay Baranov, as both ‘stiffed’ him. This is why Druzhik agreed on a plea bargain. As a result, a regular murder, penalised by 6 to 15 years in prison, turned into a contract killing, which is penalised from a minimum of 8 years in prison up to a life term.

Two birds with one stone

Druzhinin testified in court that while planning out the killing, Kulibaba was assuming that Druzhinin might eventually be arrested. Should that have happened, he promised to raise the bounty tenfold (the initial bounty on Chechel’s head was $40,000). Such a generous raise had one requirement: Druzhinin had to mention Volchek as his contractor during testimony.

“I find it most likely that Kulibaba was going to turn me in from the very start as I noticed ‘agents’ watching me as I was preparing the assassination,” Druzhinin said in court.

Vladimir Kulibaba. Photo: the press service of the Russian Wrestling Federation

Druzhinin actually had a point there. The behaviour of a random witness that rushed after the hitman is not something an average person would do: who wants to run towards the armed criminal, running the risk of becoming an extra (dead) witness, rather than running away from the scene? The whole thing looks more like a premeditated plot to catch the hitman in the act.

Kulibaba gave Druzhinin 500,000 rubles (over $20,000 at the time) to prepare the assassination. The killer spent half the money on preparation (the pistol, the car, the tracking of the victim, etc.) and left the rest in cash in his rental apartment. Before approaching Chechel’s car, he asked the man who drove him to the house where the victim lived to visit the rental apartment should he get arrested, and gave him the keys to it. The accomplice was instructed to get rid of the weapons stored in the apartment and to collect the rest of the money.

He was told to give 150,000 rubles to Druzhinin’s mother, leave some part of the money for an associate of Druzhinin’s, and to keep the rest (around $5,000).

The accomplice indeed visited the apartment and collected the money, but neither Druzhinin’s mother nor his associate got their shares. So, it was no wonder Druzhinin was willing to get revenge. Additionally, he got a chance to reduce his prison term significantly.

“In exchange for the testimony against Kulibaba, Druzhinin was promised to have his term reduced (he was eventually sentenced to 20 years in prison for assassinating Chechel — Novaya-Europe), Makarov says. “Druzhik kept to his end of the deal and even testified in court where he directly called himself a hitman earning his living by contract murders. He told the court in detail when and how he met Kulibaba, how the latter asked if Druzhinin could assassinate Chechel, as well as where and when Kulibaba gave Druzhinin his advance payment for the contract to kill the CEO of Kaskad. However, Kulibaba was found not guilty, and the prosecutors “forgot” about the promises they gave to Druzhinin. They used some details about his earlier career that he shared while preparing for the trial, and filed additional charges against him, adding five more years to his 20 years term. So, the earliest he could be released, even on parole, was 2030.”

Support independent journalism

Why was Kulibaba found not guilty? The most common, and the most likely explanation is that the jury found Kulibaba and Baranov not guilty in 2012 because of the phenomenal work done by Yury Novolodsky, their lawyer. The attorney managed to pass Kulibaba off as the victim of “police lawlessness”.

However, other reasons behind the acquittal can be heard here and there.

“If you remember, Kulibaba was arrested several times in this case,” a former major mobster from Yakovlev’s gang who wished to remain anonymous tells Novaya-Europe. “After Druzhik provided his testimony in late 2010, Kulibaba was arrested, but soon released on pledge not to leave town. This cost Kulibaba one million dollars. Then he was sent to jail once more but was soon released again. The first time he was spending his own money, but the second time he asked us for help. So, we collected that money altogether. I don’t know who exactly took the bribe. I also know there was a bribe for the verdict, too, and I even know who took that bribe, but I will not say this: I don’t want to get killed. I’m not sure how big the bribe was, but there were rumours that the entire trial cost Kulibaba $10 million.”

To do one’s thing for the good of the state

Makarov kept in touch with Druzhinin even after the hitman had been eventually sent to a maximum-security prison.

A penal colony in Fornosovo where Alexander Druzhinin served his sentence. Photo: Russia’s Federal Penitentiary Service

“He gave me a call last August,” Makarov tells Novaya-Europe, “said recruiters from PMC Wagner were visiting his prison. He told me he was going to accept their offer. Druzhik was deceived by the Russian state several times, and he did not believe he would be released after spending a couple of months in Ukraine. But he said it was a perfect chance for him to have a change of scene and take a walk in the fresh air. He called his wife last September, told her he was going to war, and we didn’t hear from him for several months. I for one thought Druzhinin simply used this whole situation and made a run for it. Unexpectedly, he resurfaced last December. It turned out he was wounded in the knee and was in hospital. He told me he had been firmly promised a full amnesty and the removal of all convictions, as atoning for his guilt with blood. I laughed at it, and said it sounded like a penal battalion during WW2. He told it was exactly the same sort of thing. They even have blocking units who shoot those trying to escape from the battlefield. PMC Wagner does not really trust former convicts out there, so they are trying to guard against desertion. He also told me he was going to visit his family once he gets better, take a rest, and then come back: not as cannon fodder this time, but rather a blocking unit trooper. Said he was promised not to be used in the heat of the battle, and controlling cannon fodder from the rear was just what he needed, he said. He told me one more thing: he said his dream finally came true — he was now doing what he can do best for the good of the state, earning a decent coin for it.”

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]