“So basically, we’re encircled,” a guy wearing military gear with no insignia says to the camera. His body armour has a badge reading “Shkabrik” and a khaki-coloured Totenkopf patch.

“Actually, we’re almost certainly fucked,” his older comrade-in-arms says as he grins. “But fucking hell, maybe we’ll survive?” The two are sitting on stone rubble, their backs leaned against a brick wall. Gunshots can be heard nearby.

This 20-second-long video emerged in Z-channels and pro-war sections of Russia’s social media in late November. “Two followers of the Kyiv regime are encircled, and they make a video about it,” people wrote in the comments.

“This is Spartak, there’s no doubt about it, I’m 100% sure,” Stas Kuryanov says as he recognises his twin brother in the guy who’s hoping to survive. Spartak Kuryanov used to be a prisoner from a maximum-security penal colony in Russia’s Saratov region. Stas received this video from a PMC Wagner representative. He also received a cross necklace, two medals, a merit certificate from Leonid Pasechnik, the leader of the so-called Luhansk “people’s republic” (“LPR”), and the death certificate of Spartak Kuryanov, born 1990. The paper says Spartak lost his life on 23 October 2022 in Artyomovsk, “DPR”. This is what Bakhmut used to be called.

Spartak Kuryanov was serving time for robbery and left prison on 30 September 2022 despite being scheduled to do so only on 11 July 2025. Alongside other recruited convicts, he headed for the airport and then to a PMC Wagner training camp.

What could force a 32-year-old man who was set to be released in less than three years to go to Ukraine for war? And why no supervisory or monitoring authority that his uncle, a human rights defender, addressed, could prevent his recruitment, which is a criminal offence?

Maximum security penal colony #2, Engels. Satellite footage. Photo provided by the author

‘Bloody cannon fodder’

“Aren’t you guys being recruited out there? I hear they visited the#10 prison,” this is what Pyotr Kuryanov, an expert with a foundation protecting convicts’ rights, texted Spartak in late September as he found out PMC Wagner’s envoys arrived in the Saratov region. “Is this bullshit for real?” Spartak responded. When Pyotr told him crowds of convicts had already been sent to frontlines, his nephew was actually interested, asking what was really going on. “That’s bloody cannon fodder,” Pyotr told him. He failed to bring this home to Spartak, though, who did not believe there was no chance of survival.

Spartak was serving a 6-year sentence at the#2 colony in Engels. He was found guilty of robbery in July 2019. According to the verdict, on the night of 14 December 2018, Spartak attacked a woman in the street and, having punched her several times on the head, tried to seize her phone worth 500 rubles (€6.3), and when this failed, he committed a robbery attack on another woman, and seized her smartphone worth 1,500 rubles (€19), also using violence. He was also trying to steal her bag but failed to do so as he was interrupted.

For this, Kuryanov was sentenced to six years in a maximum-security prison. An aggravating circumstance was the fact that he had been convicted twice before: to eight months of probation for fraud while he still was a minor, and while still on probation, to 9 years and 8 months for murder. He served his time at the maximum-security prison and was released in May 2018. After his release, he even set up a social media account where he uploaded several photos of him: a stiff face and a wan look on his face. And then he was detained for robbery the following January.

He was assigned to the#2 prison for repeat offenders. This prison was the only one in the Soviet Union to be awarded a commemorative ruby badge “For Labour Valour” by the decision of the Communist Party and the government. People who know the place say there is neither maximum security there (the prison has an underground casino, as well as supplies of drugs, booze, and cell phones) nor justice: an inmate needs very little to fall out of favour with the prison guards and cause himself problems. And Spartak also had problems, apparently, as he was serving time in a punishment cell for the past two years.

Поддержать независимую журналистику

Независимая журналистика под запретом в России. В этих условиях наша работа становится не просто сложной, но и опасной. Нам важна ваша поддержка.

‘A one-way ticket’

Pyotr Kuryanov often video called his nephew and could even see what the cell looked like: the table and the inmates sitting around it. Spartak was reluctant to discuss the Ukraine war, saying he wasn’t quite versed in this topic. He made it clear to his uncle that such talks were discouraged. “By the warden?” Pyotr used to say as he bantered with his nephew, although he was aware that the common rule among inmates was that politics was not supposed to be discussed while inside. A politics discussion might lead to an argument where someone might be offended, and what if OMON (special police) breaks in one day and beats everyone up — and who will help you if this happens?

Pyotr would share videos of Ukrainian settlements after shelling and articles on the consequences of Western sanctions.

“Spartak would agree that the country was in an economic downfall. For some reason, I was certain that he had the correct view of what was going on, and I wasn’t concerned he could have gone to war,” Pyotr says.

When he asked his nephew about the recruitment, he just wanted to find out if PMC Wagner’s envoys were actually welcome at the prison. He knew that in some prisons, they waved them off, while in others, inmates would actually sign up.

That is why Pyotr became alert when Spartak did not believe him that convicts were doomed to become cannon fodder on the front lines. Pyotr sent him a video from a Ukrainian Telegram channel, showing the interrogation of a captive PMC Wagner convict. “That’s another option for you,” he wrote and added a smiley, meaning that getting captured was also possible.

“Well then I’m going,” Spartak replied, and it was unclear whether he was serious or kidding. Kuryanov realised what his nephew’s intentions were when he told him that it was more difficult to get captured back then than it used to be before, and Spartak replied: “I’m not going to, it’s a one-way ticket for me.”

This was similar to what Yevgeny Prigozhin, the founder of PMC Wagner, used to say in his “motivational speeches” before convicts. He would say that everybody who joined PMC Wagner would get a one-way ticket, and none of them would return to prison. Prigozhin would also say his job requirements: “murderers and robbers are wanted in the first place”. Spartak’s criminal history matched the description perfectly. Soon thereafter, Pyotr’s source in the prison told him his nephew was apparently preparing for departure.

Consensual crime

“Is it possible that he actually gave his consent?” a secretary with the regional public monitoring committee asked Pyotr Kuryanov when he told her his nephew would be taken into the combat zone within a couple of days by some public military company and asked her to address the situation (Novaya-Europe has the recording of this conversation). “Consent to what? To committing a criminal offence?” Pyotr asked her in return. Apparently, the secretary who introduced herself as Kristina was unaware that recruiting was a criminal offence in Russia (Article 359 of the Criminal code, penalised by 4 to 8 years in prison), same as participating in an armed conflict as a hired gun (3 to 7 years in prison).

The woman referred to numerous videos on Telegram where convicts were being told during recruitment what consequences their decisions might lead to. “They cannot send him there against his will, can they?” she asked. She did not clarify, however, what does it have to do with someone’s consent when it’s about someone preparing to commit a crime. Russia Behind Bars, a non-governmental organisation providing legal and humanitarian assistance to citizens facing Russian investigations and the penitentiary system, reported instances of such “consent” when convicts were recruited with a prosecutor present and were asked to state their willingness to become mercenaries on camera.

The same day he spoke to Kristina, on 26 September, Pyotr filed a grave crime report to two more institutions: the prison itself and the General Administration of the Federal Penal Correction Service in the Saratov region. In both statements, he asked to prosecute the employees of the prison “who, in violation of the current legislation, with a clear excess of their official powers and with the assistance of PMC Wagner, were preparing to illegally transfer Spartak Kuryanov, born 9 February 1990, a punishment cell prisoner, to the area of hostilities and to illegally grant him a firearm”.

Another inquiry was filed by a local human rights newspaper to the regional prosecutor. Not hoping for a prompt response from law enforcement agencies and “public controllers”, Pyotr asked a friend of his, a lawyer, to visit his nephew in the prison, so as to prevent him from being sent to Ukraine “just in case”.

The response from the interim prison warden arrived two weeks after Spartak’s funeral. Other letters remained unanswered.

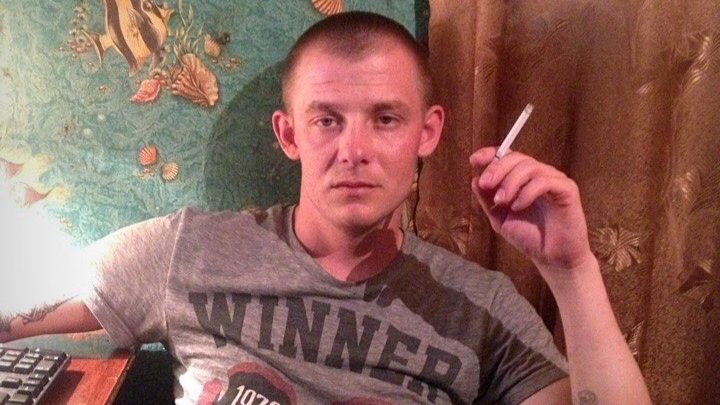

Spartak Kuryanov Photo: VK

Before being sent to Ukraine

“He had no health issues, otherwise he would not have been sent to war. He was allegedly assigned some diagnostic testing (at a notorious prison TB hospital — Novaya-Europe), says lawyer Alexander Kalabin.

According to him, his client was taken to this hospital a couple of months prior to joining PMC Wagner. The “hospital” in question made headlines in October 2021 after media published footage of torture and rape from the “penitentiary service archives”, smuggled abroad by Sergey Savelyev, a former convict who attended the place. And although since that time, around 15 criminal cases were initiated against the employees of the institution and their henchmen, and its former chief was arrested, suspicious deaths in the hospital continued: a prisoner committed suicide there again last August.

Spartak’s lawyer believes his client was sent to the hospital in an act of intimidation, although he is unaware of the reasons behind it. After Kuryanov Jr. was released from hospital, he was put into a punishment cell again. “It is a cell that accommodates six to eight prisoners, and their beds are attached to walls during daytime, so they’re not allowed to lie on those. Prisoners are allowed to walk in an interior yard, three by four metres large, once a day, and take a shower once a week. They spend the rest of their time in this cell,” Pyotr describes the conditions within the punishment cell.

“After a normal person barely sees any daylight for almost two years, they start going insane,” says Alexander Kalabin who was raised in the same neighbourhood as Spartak.

A lawyer, he would periodically visit him in prison. He was not trying to ensure parole for his client, but rather helped him solve violations of incarceration conditions. For instance, Kalabin says his client would sometimes not receive a meal or be handed dirty, lice-ridden laundry.

By request of Pyotr Kuryanov, Kalabin arrived at the prison on 28 September. He received his visit order, and then had to wait for a long time to get his pass. After a few hours, he was allowed inside a room divided by a glass wall pierced with holes for communication. “Those were like drill holes,” Alexander says. He had a CCTV camera behind his back, and a prison guard would supervise the meeting through a window. It was impossible to have a private conversation in such conditions.

“I’m not going anywhere! Don’t know where Pyotr got that from,” Spartak said about the recruitment. Kalabin says his client was dressed in a usual manner: a prisoner’s robe with a label and a cap. “He was calm as can be and tried to act naturally as if nothing had happened,” Kalabin recalls.

After exiting the prison, he gave a call to Pyotr and told him how the meeting went. He gave Pyotr another call in just two days and told him Spartak was going to war. Kalabin received this information from a source in the same prison, another man recruited by PMC Wagner.

Soldier of fortune with poor eyesight

“I loved going to a shooting gallery, and he just couldn’t do that. No wonder, he’s not made for shooting, he was almost blind and wore glasses!” says Stas Kuryanov about his brother’s “military skills”.

He claims he used to pretend to be Spartak during military preparation classes in school: the two were twins, so it was no big deal. Spartak did not wear glasses for long: he ditched it after a while and told his parents he lost it.

“He was perfectly fit physically, though. I used to be a good shooter, but he was an even better fighter,” Stas says.

It is unknown if Spartak had any other traits that may have been useful at war: he never served in the army and was not even liable for draft.

“Where would he have any skills from? He went to prison when he was 18 and was released when he was 28. Spent a year on the outside and returned there,” Stas says with sorrow.

The two were out of touch with each other for the past two years. It was a surprise when Spartak gave his brother a call in late September and told him he was going to war.

“First, he said everyone gave up on him and nobody needed him. And then he went: ‘What did I do in my life? I’m a disgrace to our parents, to you, and our cousins… Maybe I’ll clear my name this way,” Stas recalls his brother’s words.

The call lasted about 20 seconds, so the two apologised to each other and said their goodbyes. They never talked to each other again.

Spartak did not tell his brother how many inmates went to the frontline alongside him. It is only known that at least one more convict from the same prison joined the mercenary group, another client of Alexander Kalabin’s. He says the man in question lost half a million rubles (€6,400) in the prison casino. His mother paid the debt, but the man decided to go to war to earn this money and repay her.

‘We’ll bury him without your military bullshit’

Obviously, Spartak and his fellow traveller were among those 10,000 prisoners that dropped Russia’s official prison population from 348,000 to 338,000 people last September. Mediazona analysed official stats provided by the Federal Penitentiary Service and found out a total of 23,000 male convicts had “disappeared” from Russia’s prisons in September and October as PMC Wagner was actively recruiting.

The next time Stas learned something about his brother was in early November. He was at work when a PMC Wagner representative called him and said that Spartak had lost his life, blown up by a land mine. He was certain about Spartak’s death as there were numerous witnesses of this. The death certificate, issued on 10 November in Rostov-on-Don, indicated the date and place of Spartak’s death: 23 October, “Artyomovsk, DPR”. At the same time, for some reason, the letter from Leonid Pasechnik, the head of the “LPR”, said that “Spartak Kuryanov gave his life for the freedom and independence of the Luhansk People’s Republic.”

Spartak Kuryanov’s decorations. Photo provided by the author

Spartak’s documents, decorations (a PMC green ribbon medal and a medal “For Courage”) and the “compensation” were handed over to Stas Kuryanov by PMC Wagner’s representatives in person. They met in Samara in a hotel room. Their manner of speaking and lack of tattoos made Stas believe they were not convicts.

Spartak’s body was going to be delivered to Engels in the Saratov region where his parents were buried. However, this took a lot of time. “You have to wait,” PMC Wagner kept telling Kuryanov’s relatives. They explained that issues with Aeroflot, Russia’s state-owned air company, were behind the delay. At some point, a PMC representative suggested burying Spartak at a cemetery in Samara on the Alley of Heroes, with military honours. The relatives refused to do so, though.

“I told them: ‘No, guys, bring him over here. We’ll bury him without your military bullshit! In a normal way,” Stas recalls the conversation.

Due to the body transportation issues, Spartak Kuryanov was only buried just before the New Year’s Day, next to his parents. Only relatives and friends were present at the ceremony.

Two weeks after the funeral, on 12 January, Pyotr Kuryanov received a response to his September request from the prison warden: “We inform you that in accordance with the Federal Law of the Russian Federation of 14 July 2006#152 “On Personal Data”, the requested information cannot be provided,” wrote A.A. Simonov, the interim prison warden. As of early February 2023, Pyotr Kuryanov has yet to receive any response from the regional penitentiary service, the prosecutor’s office, and the local public monitoring committee.

Делайте «Новую» вместе с нами!

В России введена военная цензура. Независимая журналистика под запретом. В этих условиях делать расследования из России и о России становится не просто сложнее, но и опаснее. Но мы продолжаем работу, потому что знаем, что наши читатели остаются свободными людьми. «Новая газета Европа» отчитывается только перед вами и зависит только от вас. Помогите нам оставаться антидотом от диктатуры — поддержите нас деньгами.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]