It was 2018 when Alexander Bortnikov, the director of Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB), declared that the armed bandit groups in North Caucasus had finally been put out of existence. It seemed as if the terrorist menace Vladimir Putin capitalised on to rise to power was no longer a thing.

However, the FSB started finding new “future-oriented” focus areas: Crimean Tatars, Columbiners, and “Ukrainian neo-Nazis”. The notion of terrorism has been expanding its definition during the last 20 years and reached its peak after the invasion of Ukraine had started.

The Russian Prosecutor General’s Office recorded three times as many terrorism crimes in the past six months alone than in 2012. Novaya Gazeta Europe has researched several hundred FSB reports on terrorist attacks Russia’s secret service had prevented in the latest decade. Here’s our insight into what kind of people are being detained most often, who the “Ukrainian saboteurs” are and how the Russia-occupied Crimea became one of its most “dangerous” regions.

In April 2013, a counter-terrorist operation took place near the settlement of Gimry in Russia’s Dagestan. The extensiveness of the operation and the actions of the law enforcers resembled those of the Chechen Wars.

It started off when the security officers noticed a group of armed insurgents in a gorge near Gimry, led by the boss of the largest Islamist gang in Dagestan. The FSB blocked Gimry, concentrating several special units near the village, as well as armoured vehicles and helicopters. Hundreds of local residents fled the locality when gunfire erupted. They had been dwelling in a square near a mosque in a neighbouring village for a week with no food or even tents for them to spend the nights in, Human Rights Watch reported back then.

Meanwhile, the FSB men were looting people’s houses, breaking doors, smashing house appliances and slaughtering livestock, the human rights organisation says. Eventually, possessions of 450 families were destroyed, according to the Dagestani governor’s PR office. The FSB blew up the houses of the 10 families whose relatives were suspected to be linked with the underground resistance.

After the separatists had been routed in Chechnya in 2009 (this is when the counter-terrorist mode was formally waived in the region), some insurgents moved to Dagestan, Ingushetia, and other regions in the North Caucasus. They would blow up police stations and attack police officers, while the FSB would persecute and kill the insurgents.

The agency killed at least 570 “Islamists” in the past ten years, reported preventing over 300 terror attacks in the North Caucasus, and declared its victory in the war against the underground movement in 2018.

The counter-terrorist activities of Russia’s security services halved after the reprisal against the insurgents: the FSB reported preventing 46 attacks in 2016 and only 26 of those in 2017.

It looked like the terrorism menace had finally been obliterated, and that it was high time the staff of the FSB’s anti-terrorist committee be reduced. However, the security officers started finding new “future-oriented focus areas”. For instance, the year 2020 saw a sharp rise in the number of reports regarding prevention of school shootings, and the pre-war period had numerous prevented attacks by “Ukrainian nationalists”.

The FSB executed a total of 48 counter-terrorist operations in 2020, a record within a six-year period. After the war had started, the efforts of Russia’s security agencies were redirected at fighting a new underground movement: more than half of the reported prevented attacks had been allegedly plotted by Ukrainian “neo-Nazis” and the country’s Security Service, namely seven attacks in November alone, as per the FSB’s information.

“The FSB directs its resources at the things the state considers a priority. Preventing terrorist attacks means loads of reports and demonstration of efficiency in responding political requests, which change their nature depending on the circumstances at any given time,” says Sergey Davidis, the head of Memorial’s Support for Political Prisoners project. “Usually, when there are no special political events, the most natural target for the FSB are Muslims. They also focus on children’s safety after notable school shootings. Now that the war is on, it’s understandable that the government is willing to demonstrate that the country that fell victim to aggression has major terrorist activity. This is how they justify their own criminal activities in the eyes of the people.”

Victimless attacks

Two “Ukrainian saboteurs” were shot dead by the FSB in the Voronezh region on 23 November, allegedly attempting to blow up power facilities. As The Moscow Times found out, the Rossiya-1 TV channel passed a logo from the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. video game off as a badge of Ukraine’s nationalists in an FSB-shot video, while the alleged Ukrainians turned out to be airsoft players from Voronezh.

Prior to the war, the FSB’s primary targets were armed insurgents and suicide bombers. The agency has prevented 30 bombings in crowded places in the last 10 years, according to official reports. After the war started, the FSB focused on anti-war acts. Half of the attacks the agency prevented in 2022 did not threaten people’s lives: the “terrorists” attacked the buildings used as offices for local authorities or attempted to cripple railroad tracks used to transport military equipment to the front lines.

Dmitry Lyamin, a resident of Russia’s Ivanovo region, attempted to set a local conscription office on fire this spring. His Molotov cocktail did not penetrate the window, only damaging the glass and the casement. The Investigative Committee initiated a criminal procedure on the account of damage to property, but the FSB joined the investigation in the summer, and Lyamin was accused of committing a terror attack on 4 July and added to the terrorists register two days later.

No fewer than 10 attempts to attack administrative buildings or conscription offices have been treated as terror attacks by the FSB since the start of the Ukraine War. The accused are facing up to 20 years in prison each.

“Terrorism is primarily a demonstrative action which threatens ordinary people,” says Sergey Davidis of Memorial. “The state may treat arsons of its conscription offices as crimes, of course. But the menace to the community triggered by damaging a door somewhere in the countryside is not sufficient to treat this as a terrorist attack.”

Half of the attacks prevented in 2022 were set up by “Ukrainian nationalists”, the FSB says. In the first six months of 2022 alone, 32 out of 61 crimes of terrorist nature were prepared by “neo-Nazis”, as per the FSB reports.

The agency took an interest in pro-Ukrainian ultra-rightists shortly before the start of the war. In two years, the FSB organised several massive raids on “neo-Nazis”: 106 people were detained in December 2021, 60 were detained in March 2022, and up to 187 in September 2022.

All the detained individuals were claimed to be members of the Ukrainian neo-Nazi organisation called Maniacs. The Cult of Murder (MCM). The pro-Kremlin media link the organisation with Ukraine’s Security Service and even “Western secret agencies”, citing the FSB.

Over 150 members of this community were detained in the last two years, allegedly guilty of preparing terrorist attacks in Russia. All the details of the investigation are classified, Sergey Davidis says, but what is found in open sources does not look convincing to human rights defenders: “A hub and spoke organisation called Maniacs. The Cult of Murder with hundreds of members involved in preparing terrorist attacks is more of a joke really. A construct like this, when the FSB makes up a hub and spoke criminal organisation is commonplace for them.”

How ‘terrorism’ moved into Crimea

The FSB detained six Crimean Tatars in August, accusing them of setting up a religious terrorist organisation called Hizb ut-Tahrir.

Enver Krosh, the alleged leader of the organisation’s cell, got beaten up by the law enforcers for refusing to unlock his mobile phone while being escorted to Simferopol. He was tortured with electricity in a basement of a police station in Dzhankoi in 2015, and put to jail for 10 days in 2018 for a photo with a Hizb ut-Tahrir flag on his social media.

Hizb ut-Tahrir is a political party established in 1953 in East Jerusalem by by Taqi al-Din al-Nabhani, a judge of the local sharia court. Its goal was declared to be non-violent unification of “all Islamic lands”.

Russia’s Supreme Court banned the organisation in 2003 alongside Al Qaeda and Taliban. The trial was a closed one, and nobody knows why Hizb ut-Tahrir was banned in Russia.

Different estimates say that there were up to 10 thousand supporters of the organisation in Crimea in 2013. The members of Hizb ut-Tahrir, which is not banned in Ukraine, faced large-scale persecution after the peninsula’s annexation in 2014.

In October 2022, Crimea entered the list of top five Russian regions both by the number of FSB-prevented attacks and terrorism-related crimes recoded by the Prosecutor General’s Office, surpassed by Moscow and the North Caucasian republics where the level of terrorism has always been high.

Top-10 regions by number of crimes of terrorist nature

Crimea hit the top-5 most “terrorist” Russian regions in just 9 years

“Before Russia annexed Crimea, the peninsula enjoyed much diversity in terms of religion,” says Maria Kravchenko. “Hizb ut-Tahrir was also present there. It turned out eventually that its ban in Russia was a handy excuse for the persecution of Crimean Tatars. Not only the supporters of the organisation faced pressure, but also their relatives and local human rights defenders.”

Hunt against schoolchildren

An 18-year-old student committed the deadliest school shooting in the history of continental Europe on 17 October 2018 when he shot dead 21 individuals, including himself, at the Kerch Polytechnic College in Crimea.

The attack drew the FSB’s attention. The agency prevented their first “Columbine” in February 2019: while searching the house of a Khabarovsk student, the law enforcers found numerous leaflets of the so-called Russian National Unity, “symbols of school shooting”, and a rifle.

Many children switched to online education as the COVID-19 pandemic started, so there were no school shootings in 2020. The FSB, however, prevented 10 plotted “Columbines”, their record high. Although there were shootings in Perm, Kazan, and Izhevsk in 2021, the FSB’s interest for schoolchildren started to decrease: the agency reported preventing only five terrorist attacks of the kind in 2021, and just two in 2022.

Russia’s Supreme Court declared the “Columbine” movement a terrorist organisation on 2 February 2022; the court session was a closed one.

“The ban on Columbine is a true honeypot for moving up the ranks,” Maria Kravchenko says. “There is no unified organisation. Only a handful of teenagers interested in the macabre might decide to go to school with a rifle. At the same time, it is possible to initiate criminal procedures for plain sharing of information regarding school shootings or for mere talk in a company of friends. Only psychologists and teachers are able to prevent such tragedies, but the ban on ‘Columbine’ threatens them, too, as they may face persecution for discussing the topic with children or failing to report that a child is interested in the topic.

The FSB began to take an interest in teenagers back in 2016 when the State Duma lowered the age of possible criminal liability to 14 years for certain crimes, including violent upheaval and terrorism.

Three teenagers faced criminal persecution four years later, being the youngest “terrorists” in Russia’s history. The schoolboys were discussing a “blow up” of a model of the FSB headquarters constructed in Minecraft, a video game. The three were 14 years old when the criminal procedure was initiated. A court in Khabarovsk eventually sentenced one of them, namely Nikita Uvarov, to five years in prison.

A total of 92 underaged “terrorists” have been convicted in Russia during the past six years, mostly for posting “public calls for terrorist actions” online. Two years ago, the youngest “terrorist” on the register was 17 years old. Now there are 12 underaged individuals on the list; the youngest of those turned 15 this summer.

“The FSB realises that, starting from a certain point, the young generation had become the least loyal to the current regime out of all age groups, and therefore requires special attention. This is why specific effort is directed at intimidating the youth,” says Sergey Davidis of Memorial.

How terrorism expanded

Alexey Kungurov, a LiveJournal user from Tyumen, was sentenced to two years in a penal colony settlement in 2016 for his post titled “Whom do Putin’s “falcons” really bomb?” The investigators considered Kungurov’s criticism of Russia’s military campaign in Syria to be “justification of ISIS activities”; Kungurov was later transferred to a real prison. He was released in 2018 and left Russia as, he says, the law enforcers threatened him with new persecution.

ISIS was added to Russia’s list of terrorist organisations on 29 December 2014. According to official reports, the FSB prevented no fewer than 90 terrorist attacks plotted by ISIS supporters in 10 years, but, as Memorial noted, people were most commonly convicted for justifying the actions of Islamists.

Large-scale persecution started exactly after the ISIS had been banned, and the Criminal Code’s Article 205.2, “Calls for, or justification and promotion of terrorism” became the most common terrorism crime in 2018. Only two people were convicted under this article in 2013, followed by 26 individuals in 2015 and 199 in 2021.

The notion of terrorism has largely expanded in the past 20 years. There was only one article in Russia’s Criminal Code of this kind in the 1990s: Article 205, “Terrorism”. Now there are eight such articles, and seven of those allow for a potential life term in prison. The list of terrorist crimes was expanded to financing terrorism, assistance in committing terrorist attacks, and calls for terrorism online.

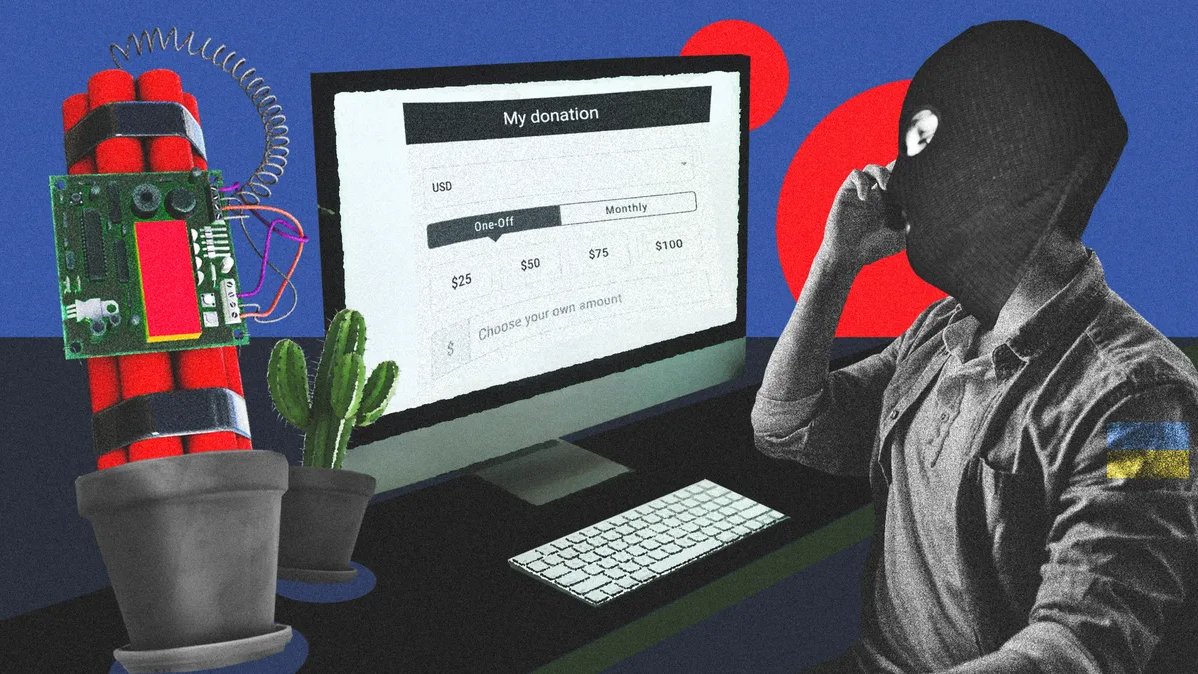

It is now possible to go to prison both for plotting a metro bombing and donating money to the Anti-Corruption Foundation, Alexey Navalny’s project. Russia’s Office of Prosecutor General recorded three times as many terrorism crimes in the latest six months alone than in 2012.

The FSB reported preventing a series of terror attacks in the occupied regions of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia after the start of the invasion. Article 361, “An act of international terrorism”, introduced long before the Ukraine War in 2016 but previously unused, was implemented in the case.

“Now that the “special operation” is ongoing, the anti-terrorism laws will be used extensively for the simple reason that some military actions may be easily defined as terrorism. This is already happening; and the statistics will only grow with time,” says Maria Kravchenko, an expert for the Sova centre.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]