According to media calculations, in August 2022 — before mobilisation had been announced — Muslim regions of Russia were among the regions with the biggest number of casualties in the Russia-Ukraine conflict. In the top ten, Dagestan was at the top of the list, Bashkortostan came fourth, and Chechnya — tenth. Tatarstan ended up after the Yekaterinburg region, at 12th place.

Furthermore, considering the inaccessibility of information on Chechnya, it would be naive to rely only on public data. With the number of people Ramzan Kadyrov was able to mobilise for the “special military operation”, his losses should be significantly heavier. Although it should be noted that not all people recruited for Kadyrov’s military units are Chechnya natives.

One way or another, “ethnic-Muslim” component is quite visible among the soldiers on the Russian side in general and among the people being killed in this war in particular. And if there is no point in talking about the motivations of people forced to mobilise, when it comes to volunteer fighters who went to the war, one of the reasons for going, among dire financial circumstances and dependence on local authorities, was ideological indoctrination.

The paradox here is that during ideological preparation for the “special military operation” Vladimir Putin and other advocates for the “Russian world” constantly appealed towards “defending Russians and Orthodox Christians” and the idea of “one nation”, which Ukrainians and Russians allegedly make up — both are Slavic people and Orthodox Christians. However, the people who are being convinced to fight in this war are neither Slavic nor Orthodox, which requires a lot of creativity from propaganda aimed at Muslim audience.

National imagery of Imperial mobilisation

These goals are being met both on the national and religious levels. For example, in Bashkortostan, the central symbol of local residents’ mobilisation for the “special operation” was Minigali Shaymuratov, Soviet general and native of the former Ufa Governorate, killed in Donbas during the Great Patriotic War.

Minigali Shaymuratov. Photo: Wikimedia

Shaymuratov is a perfect figure that combines state-wide character and national flavour. This is what sets him apart from the two other people in honour of whom the three Bashkortostan battalions are named: Russian Ufa native paratrooper major Alexander Dostovalov and leader of the Bashkir uprising Salawat Yulayev. While Dostovalov’s image does not resonate with ethnically focused Bashkirs, Yulayev, a Banderite of his time, makes the Russian part of the local population nervous.

Meanwhile, the image of Shaymuratov is for everyone — for both Tatars and Bashkirs, because he is “local”, and for Russians, because he “died for Russia”.

Still, pro-government propaganda tries to use characters like Salawat Yulayev for its goals, too, even though it is challenging. The same thing is being done with another historical figure who fought against the Russian Empire, just like Yulayev — Dagestani Imam Shamil. Despite the fact that he spent several decades fighting for independence of the Caucasian Imamate from Russia, today his name is used to mobilise native Dagestanis for warfare, the original goal of which was “restoration of Russian lands”.

Together with national symbols, quasi-religious leaders and reasons are being actively used to draft Russian Muslims.

Away from ‘Russian world’ and then back to it

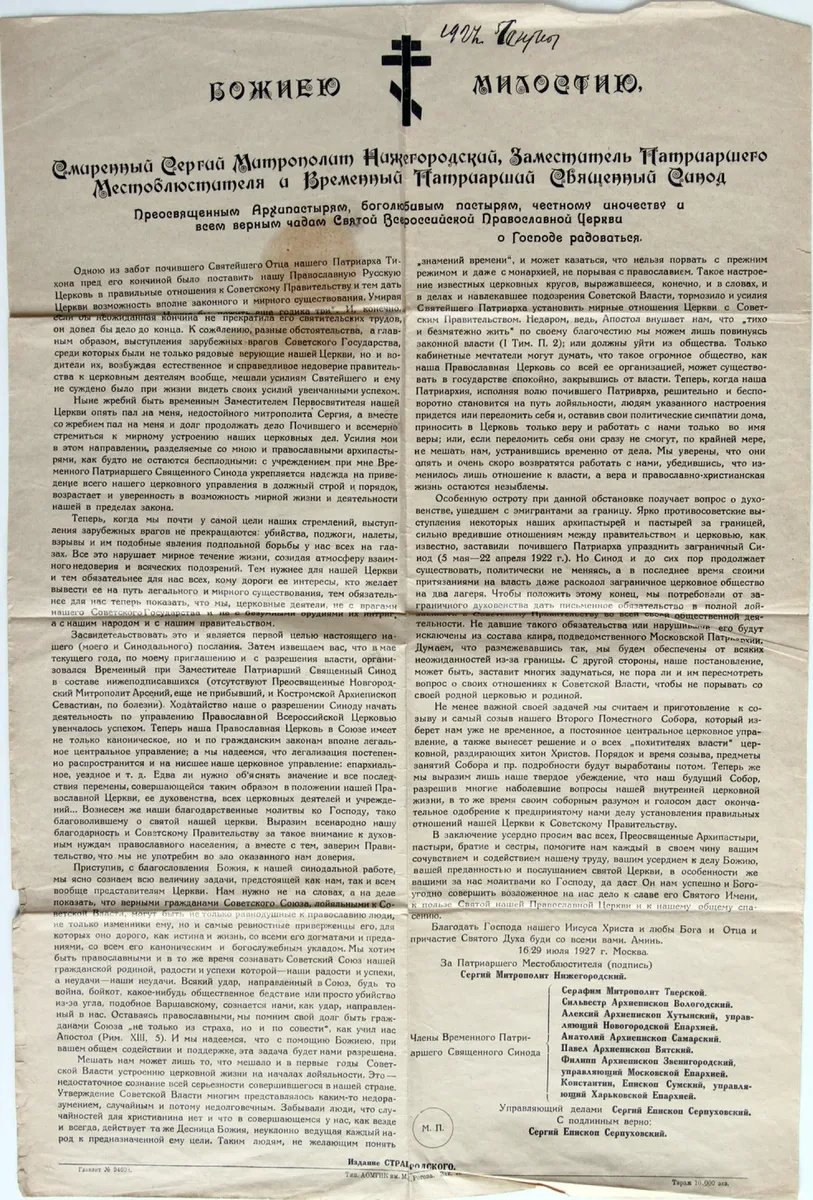

In Soviet Orthodox circles, the term “sergianism” became infamous. It derives from the figure of Patriarch Sergius of Moscow. It was he who in his Declaration dated 1927 called upon Orthodox Russians to accept the Communist government, hostile towards them, as their own. Muslims who had not suffered any less than Orthodox Christians under Communist rule experienced their own “sergianism” in the Soviet times, too. That symbolic figure was based on Mufti Abdurhaman Rasulev who used to send letters of support to Stalin and receive thank-yous in response.

Leaflet with the text of the Declaration by Patriarch Sergius. Photo: Wikimedia

The collapse of the totalitarian regime gave way to wishes of emancipation from tight government control for the Muslim community, too. How this story ended for all-Russian Muslim religious institutions is well known. However, the evolution of certain dissidents is quite revealing, considering that a lot of Muslims placed their hopes on breaking away from the “Muslim sergianism” tradition on them.

On 16 March, a conference titled Spiritual Devices and Social Mission of Religious Organisations in Context of Forming All-Russian Civil Identity took place in the city of Vladikavkaz. During the conference, a “statement by the leaders of Muslim religious organisations” was made. Citing examples from Islamic history that are canonically not applicable to non-Islamic states, the statement justified the “preventive” attack on Ukraine, while Russian Muslims that had been killed during it were called “shahids”.

The authorship and circumstances of this statement being made are also of interest. According to media reports, a number of its signees — among them not only “reliable” Talgat Tadzhuddin, Albir Krganov, and Ismail Berdiyev, but also Mufti of North Ossetia Khadzhimurat Gatsalov, several students of which had been killed by death squads and whose community had been subjected to pressure from secret services for years — said in private conversations that their signatures had been backdated and added without their consent.

The writer of the statement, according to non-refuted reports, ended up being the person whose figure evokes the phenomenon of “Muslim sergianism” without any exaggeration.

The man is Vyacheslav Polosin, known as Ali Vyacheslav Polosin — the first Russian Orthodox priest who publicly converted to Islam. Although the fact that Polosin was an Ortodox priest before converting is public knowledge, the reality that he used to be Patriarch Kirill’s assistant back when Kirill used to head the Moscow Patriarchate Department for External Church Relations is known to a far smaller number of people.

Ali Vyacheslav Polosin. Photo: islam-today.ru

This is largely what made Polosin the character that annoyed the patriarch and his close circles back when they were on their way to gaining power in the Moscow Patriarchate of the Russian Orthodox Church. Furthermore, during that time, from the end of 1990s to the beginning of 2000s, Polosin provided reasons for this annoyance not only with his public activity in his new role but also with his irreconcilable critique of the doctrine that eventually became known as the “Russian world”. For example, in his book Direct Path to God (1999), Polosin vehemently criticised the Moscow, third Rome doctrine, the despotic tradition of the Grand Duchy of Moscow’s statehood being that of a Golden Horde ulusnik (vassal — translator’s note), and Russian Imperial autocracy he had credited to “Byzantium-Mongolian colonial legacy” which he had counterposed to the Novgorod Republic.

“If the public says yes to the leadership of a chief who does not have strict moral limiters that can be cultivated only by monotheistic religion with its eternal and absolute values, then one irresponsible maniac who got his hands on power and the ‘nuclear suitcase’ will be able to destroy the entire planet in the blink of an eye,” Polosin wrote in that book just before the election of the new Russian president. He also warned Russian people not to end up “in seductive and ambitious utopias of the past”, searching for ghosts of a “holy” state unaccountable before its people, searching for “post-Byzantium all-Slavic CIS”, all of which would turn into “final death of both the state and Russian civilisation”.

What inspired the ex-assistant turned, after converting to Islam, antagonist of the current patriarch to end up on the same side as him in the war for “Russian world” is quite an interesting question, although there is no option of discussing it in this article. Luckily, Polosin is far from the only and not the most important representative of “Muslim sergianism” that today is responsible for recruiting thousands of Muslims for the “special military operation”.

Young and promising men serving the system

Support for the “special operation” by fierce loyalists like the official Muftis of Chechnya and Dagestan came as no surprise. But the similar stance taken by a number of regional Muftis was the cause for disappointment for those who had still harboured illusions about them. First of all, this applies to two young, well-educated, and promising Muslim leaders.

The first one, Aynur Birgalin, was accused by his detractors from the local Muslim establishment of spreading “Wahhabism” ahead of his being elected the Mufti of Bashkortostan. Usually, such a profile demonstrates the otherness of the respective Muslim leader from the religious officialdom, representatives of which love hiding behind “traditional Islam” and accusing their opponents of “Wahhabism”. The unusual thing was that the person who became the Mufti of one of the biggest regions of Russia at 30 years old was someone who had studied not only at the Russian Islamic University but also Egypt’s Al-Azhar University.

However, all of this did not prevent him from taking an extremely rampant stance after the “special military operation” had started: he blessed the participation of Bashkortostan’s Muslims in it, despite the fact that three volunteer battalions had already been created.

Aynur Birgalin, Mufti of Bashkortostan. Photo: Aynur Kinzyabulatov

The second case, the Mufti of the neighbouring Tatarstan Kamil Samigullin, went similarly. Samigullin even became the head of the Spiritual Administration of Muslims of Tatarstan at 26 years old, and he also is quite well versed in the questions of Islam. He obtained part of his education in Turkey, which is why his detractors linked him to one of influential Turkish communities. However weird, but neither this affiliation nor his reputation of being a sincere believer prevented him from becoming an official Mufti. With time, it became clear why he had acted within the strict lines established by the system and why he had based his public assessments of the government’s actions on infallible loyalty instead of his Islamic knowledge. He, too, supported mobilisation of Muslims for the war, however, not as blatantly as his neighbouring colleague, instead doing it pharisaically. It was indicated in the relevant statement that Tatarstan’s Spiritual Administration of Muslims did not doubt the “soundness of the Russian president’s decision, seeing as it was formed based on expert opinion and competent assessment by professionals from key agencies of our country”.

In general, these two cases, as do many others, prove one thing — however religiously educated and sincere a person seems, when they end up in a leading position in the system of official Muslim religious institutions and quasi-public organisations of Russia, they will have to cater to state policy. Just like when it came to the original sergianism, the alternatives can be either repressions, or catacombs, or exodus. All of this is known by Russia’s Muslim community modern history as well. But that is a topic for another conversation.

Kamil Samigullin, Mufti of Tatarstan. Photo: Wikimedia

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]