There are 878 people residing in the Karelian settlement of Shyoltozero, another 467 live in the neighbouring settlement of Rybreka. None of them were drafted to the war in Ukraine. The residents of these villages are Veps, a native people of the North — there are only several thousand of them left in Russia. Shyoltozero, Rybreka, and the surrounding villages used to form the Veps Volost, a national autonomy that was disbanded in 2004. However, the spirit of the Veps is unbreakable, as you will soon see. By the time the “partial mobilisation” came about, it turned out that all 14 people who were eligible for the draft in both villages had left to pick cranberries in the far-away Karelian swamps. “It’s cranberry season,” their fellow villagers said without batting an eye. During cranberry season, the Veps do not have time for call-up papers.

“Where would you go?” his girlfriend asks, pulling on his sleeve.

“Come on, stop it!” he pulls his hand free. “What else is there to do, go to jail for ten years?”

He pushes his girlfriend towards the exit. While he is pushing her into the door to open it, I tell him that there is no prison sentence for refusing to come to the draft office when summoned, the maximum fine is 3,000 rubles (€47).

“What did you say?” the guy turns around sharply to face me, while the door pushes his girlfriend back into the store. He displays a great deal of interest in the articles of the Russian criminal and administrative codes regulating the draft process.

Photo: Irina Tumakova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

All-terrain vehicle

The Karelian village of Shyoltozero is located 30 kilometres away from the border with the St. Petersburg region. The shortest way to get here is to get on a ferry on the Svir River, at the spot where it flows into Lake Onega.

Svir divides the Voznesenye village into two parts. According to Wikipedia, 170 residents of Voznesenye were among the victims of the Great Terror. There are photos of the village in 1942 available online, and it seems that not much has changed since then: even the lamp posts look the same, albeit slightly tilted. On the left bank of the Svir River, there is a Sberbank office, a grocery shop, a post office, residential houses and the village administration building, where the local draft chief is stationed. On the right bank, there are granite quarries and a couple more villages. Every day, residents of Voznesenye and its neighbouring villages have to travel between the right and left banks of the Svir River. The river is not much wider here than the Neva in St. Petersburg, but there is no bridge, though.

“For as long as we’ve lived here, we’ve been dreaming of a bridge,” a woman with a large bag queueing up for the ferry sighs. “The grocery shop is on this bank, and I live on the other one.”

The ferry. Photo: Irina Tumakova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

The ferry leaves once every hour from 6 AM to 11 PM: the trip takes about 10 minutes, if you don’t count the time spent in the queue. The only other option is to travel 80 kilometres in the direction of St. Petersburg, to Podporozhye, where the nearest bridge is located. You can also travel around the Onega Lake if you want, but the trip would cover about 700 kilometres.

“If you don’t make it in time for the ferry, you can pay five times more and they’ll get you there,” an assistant at the fishing store on the left bank tells me.

Five times more is 850 rubles for a passenger car. Residents of local villages have to spend three hours gathering cranberries to earn this sum.

Three men queueing up for the ferry exit their car. They tell me that they work at the quarry collecting gabbro-diabase, a type of Karelian granite. This stone is used to make tombstones and is considered good for the liver if it is applied to the skin; however, it is harmful to extract it, as gabbro-diabase dust is toxic. But there are no other jobs. It’s hard enough to get a job at the quarry: many people from Petrozavodsk, the capital of Karelia, are coming to work here.

“Three people from our brigade got drafted,” a grey-haired man, the oldest out of the three, says. “They called us at work and told us that there were draft papers in our name. They told us to come. We don’t even have a draft office as such, there’s a man working at the administration in Voznesenye.”

“And you came to get the draft papers yourselves?” I ask them.

Photo: Irina Tumakova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

“And why not?” the older man says. “There’s this guy that went to Turkey with his family on vacation. He came back and he tells me: his wife and his kid are having fun, but he can’t stop thinking of those damn Ukrainians there, the Banderites (originally members of the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists led by Stepan Bandera, active in the 1930s-1940s. This term is now used by Russian propaganda as a slur against Ukrainians — translator’s note). He says that he just couldn’t look at them! They came there on vacation, too. And he knows that he can’t do anything: if he beat them up, they’d kick him out from the resort. His trip was ruined. He came back, and then the draft papers came.”

“And he left to beat up some Banderites then?” I wonder.

“Why would he? He didn’t get called up,” the man answers.

Voznesenye, where people come to get their draft papers themselves, is technically not part of Karelia, it is located in the St. Petersburg region. They finally allow us to board the ferry. My car is the last one on it, but the bumper is hanging over the ramp. “Five centimetres forward!” the captain orders. Ten minutes later, I go ashore on the right bank of the Svir. I drive by the village of Shcheleyki and see the Church of Dmitry Mirotochivy, built in the late 18th century. The plaque in front of it reads: “Protected by the state”. Judging by the look of it, it isn’t protected by anyone. Then I drive by the village of Gimreka. According to the data for 2017, there are 35 people in total living in these two villages. I see a man from the group of quarry workers I talked to in the queue for the ferry. His name is Misha.

“They drafted three guys, but one of them got back,” Misha adds to what the other quarryman said. “My brother. He had a broken collarbone, they had to put in a plate. He didn’t know they wouldn’t draft him because of that. He came and got his call-up paper himself, but they sent him home.”

A hand-made vehicle with four giant wheels enters the yard. I’ve seen two of these on the road on the way here, but now I can get a closer look at it. This is the main form of transportation here.

An all-terrain vehicle. Photo: Irina Tumakova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

“It’s an all-terrain vehicle,” Misha announces with pride. “It can drive through swamps and forests. We drive them in winter and in summer. You can drive it to the swamp to gather cranberries. It can even drive through water.”

This village is where the St. Petersburg region ends and the Veps Volost of Karelia begins. There is a patch of asphalt even, but then it disappears. An unwashed Russian flag hangs from a rickety wooden house. I really need some petrol and something to eat. I ask a thin man wearing glasses standing near the house with the Russian flag if there is some kind of café nearby. He is not sure, but he thinks there is a canteen near Shyoltozero. There is indeed a canteen there, but it’s only for the quarry workers.

“I’m from Shyoltozero myself, and the mobilisation is going alright,” a man wearing a boilersuit with the quarry logo tells me unkindly. “I repeat: everything’s fine here, no one is hiding.”

Signs selling dried fish, smoked fish, mushrooms, bath brooms. Photo: Irina Tumakova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

Cranberry season

It’s October, so the days are getting shorter in Karelia: it gets dark by six in the evening. Until twilight, people are selling cranberries in jars and mushrooms in buckets along the road. Business is booming: there’s an entire camp of small houses and tents with people selling produce all year round. Raspberries, blueberries, lingonberries, cloudberries, cranberries: this year, there are more cranberries than usual. Fish is sold all year round: sun-dried, smoked, fresh, you name it. A skinny teenager in a raincoat is walking along the road, his rain boots splashing loudly in the puddles on the pavement. His hood is practically covering his face, but I can see that he has a shiner.

“Hi, Max, you’re here for the berries?” Maria, a saleswoman at one of the local shops, comes out to greet him. Max is a first-year university student at Petrozavodsk State University. He lives in the city and comes home every weekend to get cranberries.

“Berries are money,” he says with a sour face, hiding the shiner. “We gotta earn money somehow.”

“If you don’t work at the quarry here, you earn your keep in the forest,” Maria tells me. “There are good salaries at the quarry, but there’s nowhere else to work. Everyone knows where you can sell berries. A kilo of cranberries can be sold for about 100 rubles.”

There is a sign on the lamp post by the road that reads: “Cranberries, cloudberries, blueberries”. There’s another sign on a small house with a big window promoting smoked, dried or fresh fish. The house was built to function as a shop by Valera. He and his sister Natalya have been selling fish and produce for twenty years, since the factory where Valera worked at shut down. They’ve got powerful freezers inside the house, so you can even buy berries that are already out of season: a kilo of cloudberries is sold at a thousand rubles (€16). There’s smoked fish and jams of all kinds. Valera is getting fresh produce, while his wife Natalya cans and sells it.

Valera and Natalya. Photo: Irina Tumakova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

“We used to have a factory here that processed wood and made furniture,” Valera sits down on a small chair in his shop to talk to me. “There was a pottery workshop. We had a farm, we had fields. There’s nothing left. People from Moscow, St. Petersburg came here, bought everything, got their money and abandoned it all. There are cottages there, on the fields where there used to be a farm.”

Valera sells a one-litre jar of cranberries for 250 rubles (€4). He sells it himself and doesn’t hand it over to resellers.

“They’re paying 60 rubles [less than €1] for a jar!” Valera whistles. “So, I’m spending half a day knee-deep in a swamp, and then I’m gonna sell it all for a thousand rubles?”

Gathering cranberries is hard work.

“If I don’t push myself too hard, I can collect about 30 kilos of cranberries a day, but there needs to be a lot of berries,” Valera boasts. “I’ve got a friend who gathers it with a harvester. He can collect 15 ten-litre buckets in a day, but you need to carry it all from the swamp. So he spends all day carrying the buckets out of there: you need to make a lot of trips to the swamp to get it all out. It’s a three- or four-kilometre walk, knee deep in water. Not everyone has an all-terrain, and you can’t get closer without it. Plus, petrol costs money. Some people camp out in the woods for several days, and then take it all out at once.”

Photo: Irina Tumakova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

Berries and mushrooms are not the only thing on offer here. The roadside and the fences of houses along the road are littered with hand-made promo signs offering all kinds of services: from excavator operators to electricians. Some sell wood, some offer bath brooms, some — to build bath houses. There’s also a man with a cow who sells milk and manure as a fertiliser. Waste-free production. The villages practice subsistence farming: I give you manure, you give me potatoes.

“Yeah, that’s about the gist of it,” Lena, another cranberry saleswoman, confirms. “I’ve got a truck, and my husband transports granite from the quarry to the plants. When they announced the mobilisation, my first thought was: if they take him, what am I going to do with the truck? And our houses here are not like city apartments. If they take my husband, I won’t even be able to deal with our house pump: it freezes in the winter.”

Other village residents thought the same on hearing the news of the upcoming draft. Lyuba has a shop by the road built by her son-in-law.

“Do you want some fish?” she comes out to greet me. “There’s smoked trout, some pike perch, too.”

“Cloudberries, cranberries, lingonberries”. Photo: Irina Tumakova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

The shop has Soviet-style open refrigerator displays with fish wrapped in plastic. The hand-written price tags read: 1,250 rubles (€20) for a small fish. And of course, there are cranberry jars on the shelves. Whatever you sell here, you can’t go wrong with some cranberries.

“My son-in-law got the draft notice, so he went,” Lyuba sighs. “And he’s the only man in the family. He saws wood, he builds everything: it’s all on him. He catches fish, smokes it himself. We’ve got a whole farm: chickens, turkeys, quails, piglets. When he got called up, me and my daughter got so scared: what if they take him? What about us? Thank God, he went there and came back. He’s an ambulance driver, they said there is no one to replace him. But there’s a woman whose son and husband both got drafted.”

I was driving by the villages, stopping by at the makeshift cranberry markets and talking with the locals. I was on my way from Petrozavodsk to the Shyoltozero village. The village of Ladva wasn’t on my way. But the cranberry salesman told me to come there and look for the Gorinov family, where a father of three got drafted.

The Gorinov’s house. Photo: Irina Tumakova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

Ladva

Ladva is one of the largest villages near Lake Onega with a population of 2,000. It even has street lights. There are also peculiar road construction works: no new lanes are added, and two cars can barely pass one another, but they’re putting in fresh asphalt and installing white kerbs. And no one is selling cranberries. Either there are no buyers or no sellers.

“Someone has a c-cottage over there,” a short man dressed in red explains. He followed his large skinny mutt out on the road. His house was the first one with the lights on, so I stopped in front of it. The man decided not to introduce himself, but told me his dog is called Rex. I asked him about the Gorinov family.

Rex. Photo: Irina Tumakova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

“They drafted a lot of p-people here into the army,” he said with a strong stutter. “They t-took my cousins. Igor worked at a boiler room. When the draft notice came, they told him they wouldn’t keep his job. And Yura… well, he didn’t work. Just took some side jobs. He asked me for help once, to erect a monument in the cemetery. He picked berries and mushrooms in summer and autumn. His house burned down, his mother died. Then they bulldozed his house. Yura, he’s… well, you know.”

The man flicks his neck. This gesture means his brother Yura is a heavy drinker. When they drafted him, his wife said it was alright, as long as they compensate him.

Two more houses down the road did not have any lights on. Then I saw the remains of a fire, which is where Yura’s house likely was. Next to it, there was the Gorinov’s house: not much to look at, like everything else in the village besides the fresh asphalt. The owner of Rex pointed me towards it.

A woman looked out the window and then came out to greet me. It was Dima’s wife, Lyuba.

Lyuba Gorinova. Photo: Irina Tumakova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

“They took him, and so he went,” Lyuba shrugs with a frown. “Everyone says that you get 10 years in prison if you don’t show up. It was a Sunday, they handed him a call-up paper on 25 September, and told him to come to the draft office on Monday morning…”

We entered a warm kitchen. A middle-aged woman — Dima’s mother, Veronika Kazimirovna — was sitting at the table. A young guy and a full-figured, red-faced young woman with a towel wrapped around her head were sitting beside her. They were drinking a yellow drink, likely non-alcoholic beer, judging by the discarded can under the table. The younger woman was holding up her smartphone, talking to a man with a raspy laugh. A girl ran into the room to tell her grandma it was now her turn to enter the sauna. Lyuba took the phone out of her daughter’s hands.

“He’s calling us right now, ask him yourself,” she said, handing the phone to me.

The phone screen said that “Demon” was calling.

“They drafted me, which means they had to,” the man said with a laugh. “Which means they need me. Nah, I wasn’t scared of jail, I don’t care about jail. I went because it’s my duty. My duty.”

“Before your Motherland,” his daughter suggests.

“Before the Motherland,” he agrees. “We are at a training centre now, Luga-3. Our living conditions are great.”’

“They feed you well,” his mother notes.

“Yes, they do,” Dima agrees. “It’s warm. I sleep under a bedsheet. There are about a hundred of us from the Leningrad region, and the remaining 600 are from Karelia. There are four barracks here. Or more, I don’t remember. They sent some guys over there already. We were told we’re here until the 25th. Of this month.”

“October,” his daughter says.

“October,” Dima confirms.

The family didn’t have to buy much for the new conscript, Dima said, “just the tactical vest and the balaclava, the rest was provided on the spot”. I heard Lyuba quietly sigh behind me. Dima is 37 years old, but there are some men older than him there.

“Everyone has families,” Dima added. “My family is used to me working!”

“Come off it, don’t say we’re used to it!” Lyuba suddenly exclaims.

“He wasn’t working or earning any money,” his mother chimes in.

“And now I’m going to earn money,” Dima replies. “I just got a bank card and registered it in my wife’s name. They promise to pay me 47,000 [rubles, about €750] a month. Well, I don’t know how much they’re gonna pay me. I’ll probably get more soon. I’ve got a contract… I think its for three to five months. I was drunk when I signed it. We were told they’d send us off to the war on 25 October. Until then, we’ll stay here.”

Dima says that the draftees are undergoing military and political training in Luga.

“They tell us all kinds of bullshit. About Khokhols (a Russian slur word for Ukrainians — translator’s note).

We do improvised fighting in the forest. We assemble and disassemble guns.”

I heard a sob behind me. Lyuba was quietly crying. I handed back the phone to Dima’s daughter and came outside with Lyuba. She was smoking in silence, with tears streaming down her face.

“I didn’t want to let him go,” she said after a while.

“We wanted him to dodge the draft somehow,” his mother, who came out to the porch with us, said. “He’s got high blood pressure, he was seeing a doctor. But he said he’d go anyway.”

Lyuba has spent 25,000 rubles (€400) so far to get Dima ready for war. This is her monthly salary, which is considered pretty high here.

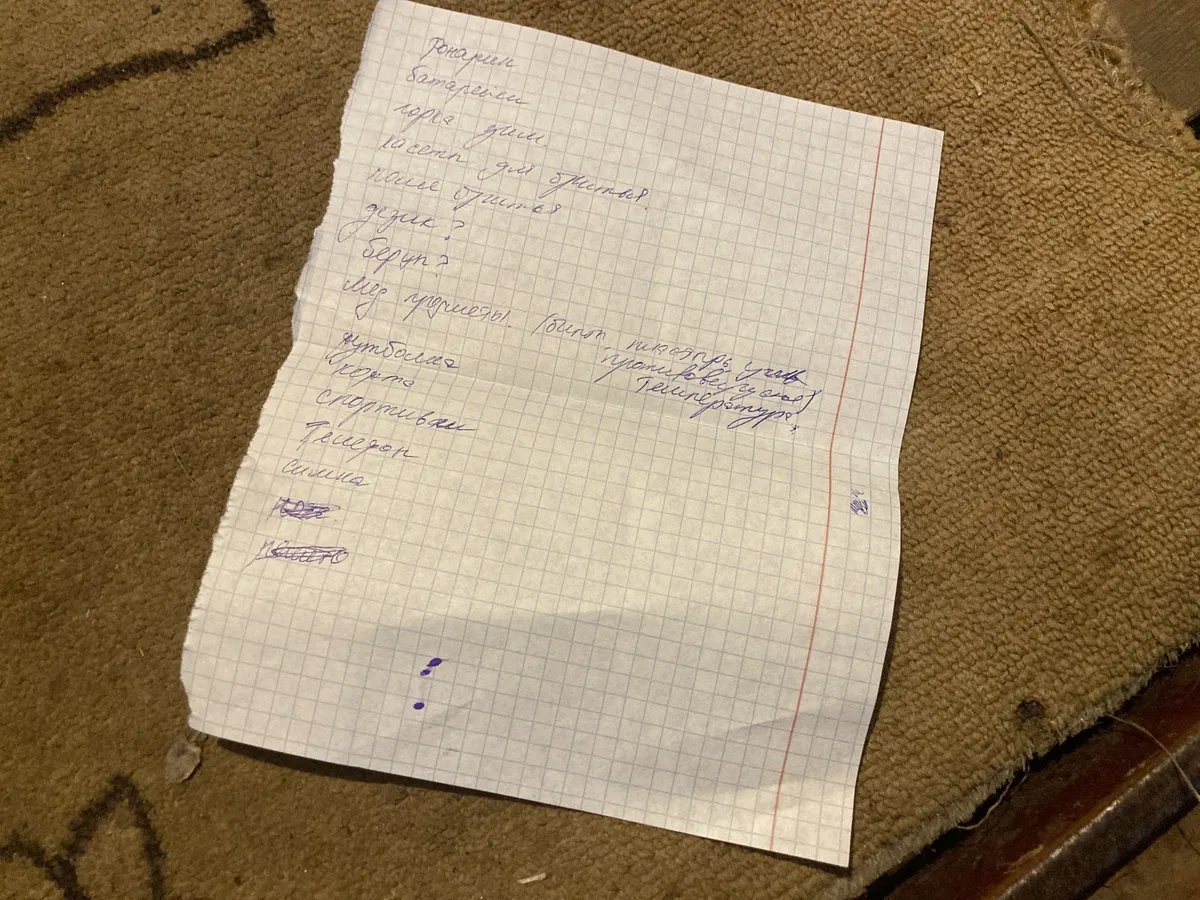

“Here’s a list, Dima read it to us, and our daughter wrote it down,” she hands me a piece of paper. “And it’s not even all of it. There’s 50,000 rubles worth of stuff. And that’s without the bulletproof vest and the helmet, I don’t even know where to get them from.”

A list of things for a conscript: “Flashlight, batteries, anorak, shaving supplies, deodorant (?), boots (?), medical supplies (gauze, band-aids, anti-viral/anti-fever drugs, a T-shirt, a sweater, sweatpants, a phone, a SIM-card”. Photo: Irina Tumakova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

“I took some money out of my pension. My pension is 16,000 rubles (€250),” Veronika Kazimirovna sighs. “His grandma, my mother, has a higher pension, she also helped. Then we’ll have to take loans. What else can we do? Who can help us?”

Lyuba wrote to Artur Parfenchikov, the governor of Karelia, to ask if he plans to support the conscripts. There are reports online of the Moscow regional government issuing 200,000-ruble (€3,180) payments to the draftees.

“Parfenchikov wrote to me… One second,” Lyuba says, going through her phone. “Here’s his response: ‘Good afternoon! We will consider the mechanism of support for the families of the servicemen.’ What does it mean? I’ve started reading up on how it’s done in the Moscow region. Their governor says: ‘The money will arrive proactively after the first salary.’ What does ‘proactively’ mean? I asked Parfenchikov whether they’ll do it ‘proactively’, too. He didn’t respond. But I don’t even need money, I just want my husband back. Alive and well.”

Shyoltozero road sign. Photo: Irina Tumakova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

Shyoltozero

On 4 October, Karelia regional governor Artur Parfenchikov announced that the region had met its mobilisation goals. Karelia has a population of 30,000, about half of them live in Petrozavodsk. Reportedly, they drafted 30 people each from villages of 1,000 residents. They planned to draft 1,000 men, and they did. The last batch of draftees left on 5 October on a bus marked “Children”. On the same day, it was reported that no one had been drafted in the Veps regions of Shyoltozero and Rybreka. They received zero draft notices there. On the 6th, the son of Galina Gennadyevna (the name was changed on her request) came back home.

“Do you know why they took them away in buses?” Galina Gennadyevna squints slyly, pouring me a cup of cloudberry tea in her tiny kitchen. An oldies song about “a road without end” has been playing on the TV for the past ten minutes, it seems. A song without end.

“Because you can escape from a train,” she answers her own question. “You can’t escape from a bus. And they didn’t let those who came to the draft office out. They gave them four hours, so that their families could buy them everything they needed. And now they’re taking them there to their deaths. You know it, too.”

In May, Zhenya Chubarin, a resident of Shyoltozero, left for the war in Ukraine. He grew up with eight siblings. He also had a wife and a two-year-old kid. He wanted to earn some money, but he couldn’t find a stable job. You can’t earn much collecting mushrooms and berries to feed so many people, especially in the spring.

“The last day Zhenya was still alive, he called my son,” Galina Gennadyevna said. “My son put him on speaker, he said I need to hear this. They took them to their positions and started handing out uniforms. He said there was some old and torn stuff, and some new gear, too. But they were told to pick their gear from the old and torn pile. Zhenya said they’re selling the new ones. They gave him a bulletproof vest, but it only had the front part, and nothing on the back. So yeah, he called my son, and on the next day, he got killed.”

Zhenya Chubarin had only fought in the war for two days. He left on 11 May and died on the 14th. As of that time, 15 people across Karelia had been killed in Ukraine and buried back home. Since then, 20 more residents of Karelia have been killed in the war. And now, their peers are waiting for a call-up card.

“I know that they always hated us in Ukraine, Russians only did hard labour there,” Galina Gennadyevna shakes her head. “But why should I send my son there? What for? My son told me: I’d rather spend two years in jail, but at least I’ll be alive then. If they come and attack us here, I will defend my country, but I have no need to go there, he says.”

A church in Gimreka.

A church in Gimreka. Photo: Irina Tumakova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

Galina Gennadyevna, who either worked at the Veps Volost administration some time ago, or simply knew everyone there, told me her version of what happened in the two Veps villages.

“You know what they do here?” she started. “A man gets a draft notice, and they fire him retroactively, the day before. Because no one wants to hold the spot for him.”

They say that the residents of the Veps villages found out the names of men that were to receive the call-up papers. On the same day, 14 young men in Shyoltozero and Rybreka remembered that it’s cranberry season. They couldn’t wait any longer: a day more, and the berries would become overripe. And they took off for the swamps. To make the cranberry collecting process more comfortable, some of the locals let the guys stay at a hunter’s lodge in the forest. And then, on the day when governor Parfenchikov announced that the partial mobilisation had been a success, they suddenly realised that they had collected enough cranberries. It was time to go home.

Делайте «Новую» вместе с нами!

В России введена военная цензура. Независимая журналистика под запретом. В этих условиях делать расследования из России и о России становится не просто сложнее, но и опаснее. Но мы продолжаем работу, потому что знаем, что наши читатели остаются свободными людьми. «Новая газета Европа» отчитывается только перед вами и зависит только от вас. Помогите нам оставаться антидотом от диктатуры — поддержите нас деньгами.

Нажимая кнопку «Поддержать», вы соглашаетесь с правилами обработки персональных данных.

Если вы захотите отписаться от регулярного пожертвования, напишите нам на почту: [email protected]

Если вы находитесь в России или имеете российское гражданство и собираетесь посещать страну, законы запрещают вам делать пожертвования «Новой-Европа».