Amid the war in Ukraine, the Baltic states are acting in a united front — for instance, they have stopped issuing tourist visas to Russians or are removing Soviet-era monuments. On the other hand, each particular country uses its own methods of opposing the Putin regime. For instance, Lithuania is planning to strip people of its citizenship for supporting Russia, and Latvia to restrict the use of the Russian language at work and at public places. Anyway, these are only plans thus far, while Estonia has already banned its colleges from admitting students from Russia since the very start of the war, and it is only when this move caused a stir that it allowed those who are already receiving an education in the country to complete their studies.

Journalist Ilya Azar travelled around Estonia and spoke to some of the local Russians unhappy about the fact that the anti-Putin campaign launched by local policymakers is affecting their lives, as well as Estonians who do not object too much to their government’s decisions.

A tank and memory

A Soviet T-34 tank has stood on a highway between Narva and the town of Narva-Joesuu since the 1970s. Narva residents liked the tank very much, and taking pictures against its backdrop used to be an essential element of their wedding ceremonies.

The tank was put on a tractor unit and taken away to a museum outside of Tallinn on 16 August, even though local residents were unhappy about it and the local administration had not authorised this. A number of other Soviet monuments in Narva and its suburbs were demolished on the same day, as well.

Yana Toom, a European Parliament member from Estonia, a red-haired woman in bright hipster-style glasses, was in Narva-Joesuu that day, a community not far away from the place. Her trip was unrelated to the tank monument.

“I like to come here, and I decided this year to give my kids some rest and take my grandchildren with me. But in the end, I have to give live interviews and waste my time on other kinds of shameful things,” Toom explains with her typical sarcasm. Her grandson and granddaughter eat ice cream at the beginning of our conversation and then run away to have some fun at a nearby playground.

Yana Toom, member of the European Parliament from Estonia. Photo by Vladislava Snurnikova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

Toom, an ethnic Russian, often criticises the Estonian government. Speaking about the tank, she points out that all the monuments that have already been demolished were owned by the local self-government, and the City Council did not decide that the tank must be removed (some of the lawmakers favour its preservation, and others were afraid to lose any support from local voters).

“The locals had been prepared for its dismantlement, and everyone had come to terms with that, but the way this was done...

Narva residents told me that a plane flying over the city had woken them up, and then people in balaclavas arrived to dismantle the tank. But why not talk about that first?” Toom says.

Locals have set up a sort of makeshift memorial in place of the tank, forming a heart with candles and roses and placing a toy tank in its centre. While I was there, Narva residents kept coming to the memorial by their cars for ten minutes or so. Men would stand silently with their arms crossed over their chests or say something angrily, and some women would weep. No police were present.

If you are unaware what actually happened here, you could easily assume that people come to commemorate some celebrity killed in a car crash.

Improvised memorial in place of the demolished tank monument in Narva. Photo by Vladislava Snurnikova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

An elderly woman tells me tearfully: “They said we’ll go to the future together with them, but I don’t know how to go to the future with them... But I do know how much the Russian people suffered, how much they built here and what’s left of this.”

She says her husband and she had come here on their wedding day, and she has also been there each Victory Day.

“This is our history and our memory. People gave their lives to liberate this land. This is so painful! So many people died, and we know what that war cost. [Estonians] visit the monument to the Nazis, and by the way, it’s not out of nothing that Russia resorted to that step in Ukraine,” the woman says, refusing to introduce herself.

“Do you support that step?” I press her to make things clear.

“This is a provocation to sow discord between Russians and Estonians,” her husband breaks in. “The Anglo-Saxons want to make another Ukraine here.”

The wife shuts him up but keeps complaining, “What’s in store for us? They say America has set off some explosion, and that’s serious!”

The opinion that the war in Ukraine was started by the U.S. is very popular among the visitors of the improvised memorial.

“All of this has been done at the Americans’ behest. Anyway, what was wrong about that tank?” an elderly man laments.

“It’s not monuments they don’t like but us, the Russians. They don’t like it that we remember everything, and so they want to erase our memory,” a dignified old man says in a trained voice, as if he were a professional actor.

“But you remember, don’t you?”

“It’s true, but I fear that our children and grandchildren will forget it, and that’s exactly why it’s been done. After all, they’ve been rewriting the history of WWII for a long time, saying that it’s America and England that won it, not the USSR. In my opinion, Estonia won’t live long enough this way,” the old man predicts suddenly.

“I am surprised that Putin is too peaceful, or otherwise he’d cut off gas and oil supply to them in the blink of an eye,” responds the man who started the conversation.

Another elderly man comes to the memorial on a bicycle and lays a picture of a tank to the flowers, the caption saying, “Many thanks for everything! Remember and will remember.”

“I come here not only on 9 May but also on other holidays. My grandfather was wounded outside of Tallinn and liberated Narva. This is not okay, they shouldn’t have touched our memories. But nothing will work for them! People have visited and will keep visiting this place,” he says, gradually rising his voice.

“But why have they done this at all?”

“We have Nazis in power! They’d better create jobs and address electricity and gas bills,” the man replies, walking away to pick up his bike.

Two different Estonias

I would recommend that those Russians who have long been absent from their country and miss it but cannot return there now should travel to Narva, where nearly 90% of the local population are ethnic Russians. The first person I met in Narva upon getting off the bus was a young man in a T-shirt featuring a Kalashnikov assault rifle on the chest and a Russian flag on the shoulder.

“Can you really walk around here like this?” I wonder.

“I bought it in Estonia, and so I think I can,” the guy answers me, putting quail eggs he bought in the store in the boot of his car. “I even have a receipt at home.”

It’s almost impossible to hear Estonian speech in the city, and therefore, a journalist from Delfi showed me a local Irish pub where bartenders and waiters speak on principle only in the official language.

Mihhail Stalnuhhin, a member of the Estonian parliament and a writer, was of course in Narva together with some of his voters when the tank was being removed. He is an outspoken critic of the demolition of Soviet monuments in Estonia, arguing that this campaign has been prompted by pro-Nazi beliefs of its initiators and Estonia’s economic problems.

“Numerous people are asking questions, as electricity bills this July were three or three-and-a-half times bigger than last July. Everyone perfectly understands that there’ll be something unimaginable with the heating this coming winter,” Stalnuhhin said.

Estonian parliamentarian and writer Mihhail Stalnuhhin. Photo by Vladislava Snurnikova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

He tells me that Estonian sawmills and the local chemical industry cannot operate because of restrictions on timber and gas supplies from Russia, and the local travel businesses are suffering from the closed borders.

“Against this backdrop, the government needs a small but a successful war, and Estonia can fight successfully only its own people but cannot its neighbours,” Stalnuhhin says with a sigh. “The tank is just a decoy and a way to show [Estonian voters] what great guys they are.”

“But why is that tank so important to you?” I ask, because I don’t quite understand why the memory of the dead should be honoured near a tank where nobody is buried.

“I believe you can’t find a single family in Narva whose ancestors did not fight in the WWII. My uncle was a pilot, and he died when he was very young, at 18. One of my grandfathers fought with the Estonian Rifle Corps, and the other one was executed as a partisan. There is a stele in Gus-Zhelezny (a town in Russia’s Ryazan region — translator’s note), and there is the name of Mikhail Stalnukhin carved on it, after whom I was named. Whoever you take here, all of them have relatives who fought, and some of them died. The same goes for the other side (meaning Estonians — author’s note), but they forget that they fought on both sides. Therefore, the country that had been a country of descendants of [the Soviet] Estonian Rifle Corps before 1991 turned later into a country of descendants of the 20th Waffen SS Division. They simply can’t understand that. Perhaps you can’t understand that, either. But to us everything is clear.”

When Stalnuhhin was getting married, he also came to the tank to have a picture.

“This tank is dear to us, it’s part of us. I’ll remind you about Arnold Meri, the first Estonian Hero of the Soviet Union, who served with the 22nd Estonian Territorial Rifle Corps. I once travelled together with him on a train at night, and he told me how everything was wiped out here with artillery fire, and the place was literally covered with heaps of dead bodies, which nobody removed for half a year afterwards. What are we supposed to do about that? Erect heaps of monuments stretching for 15 kilometres? That tank symbolised all of this,” he explains.

Just like any local, Stalnuhhin mentions the cross that was erected in 1994 in memory of the Estonian 20th Waffen SS Division at Sinimaed Hills.

“It’s like about non-traditional sexual orientation here. What happens in the bedroom concerns solely two people. If you feel some affection to the SS, what can I do about it?

We have the understanding that people may have different opinions, but they don’t,” Stalnuhhin resents.

I ask him whether he thinks that the Soviet tank has become inappropriate after Russia started the war in Ukraine, but he disagrees. Instead of answering my question, he tells me that “the things are really wild as concerns corruption and the judicial system in Ukraine” and that “Ukraine is not a European-level country.”

“What does it have to do with that?” I am a bit stunned.

“It does, because when [Estonia] expresses solidarity with Ukraine, it’s in fact hatred toward Russia,” Stalnuhhin replies. With his refined manners mixed with conservative rhetoric, he looks to me a bit like some 19th-century Slavophile author.

It appears to me that Stalnuhhin embraces the official Russian view on the events in Ukraine, although he does not say this directly.

“I have to watch my mouth, because what I say and you publish later determines not only my future but also the future of the people I work together with.”

“But regardless of your attitude toward the war, it is going on, and it obviously affects attitudes toward everything Russian,” I say.

“Well, right, let’s ban Tchaikovsky and Dostoevsky,” Stalnuhhin replies sarcastically.

“That would be too much, of course,” I agree.

“During the past war, Goethe wasn’t banned in the USSR, but Pushkin is being outlawed in Ukraine now. In such situations, I always suggest that people recall The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. After all, nobody remembers that its author wrote articles demanding that the Indians be exterminated completely,” Stalnuhhin recalls for some reason.

David Vseviov, a professor with a degree in cultural history, has been hosting the Mysterious Russia radio show for nearly 30 years. He started his lectures long ago with the Byzantine era, and one of his recent programmes was about the Cuban Missile Crisis. He believes there was no alternative to the tank’s removal.

David Vseviov, doctor of cultural history. Photo by Vladislava Snurnikova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

“When milk comes to the boil and overflows, you can turn off the stove, but that won’t help anymore. When only emotions are left, then there is no solution,” Vseviov explains the situation to me and compares the tank with the Bronze Soldier, a monument to the Soviet liberators of Tallinn (its removal in 2007 caused serious riots in Estonia — author’s note). “As a historian, I’d wish we could treat our past calmly, for we should remember both good and bad things. After all, we don’t plant former concentration camps in Poland with shrubs, we leave them as they are so as not to forget,” Vseviov notes reasonably, but then arrives at the same controversial conclusion: “But when behind this monument or another are absolutely different interpretations of history and absolutely different interpretations of events that happened [in Estonia], unfortunately, there can be no other choice.”

He explains to me that Estonians do not want to see symbols of Estonia’s occupation by the Soviet Union, over which the country lost one-fifth of its entire population.

“When we travel around India and see a swastika, it does not elicit [too negative] emotions in us, because it is placed within its inherent cultural environment there. When we see tanks with letter Z firing upon peaceful cities and civilians in news programmes, this highlights the essence of the symbol. Therefore, when someone lays flowers to the tank, they do not only commemorate those who died in that war, but they also offer symbolic support to the actions of [Russian] tanks now, and Estonia doesn’t want to tolerate this,” he says.

Unproductive Russophobia

At the end of August, Filipp Loss, art director of the Russian Theatre in Tallinn, wrote a Facebook post alleging that, with the start of the Ukraine war, “filthy rotten Russophobia has started crawling out of the woodwork” in Estonia and compared problems being experienced by ethnic Russians in the country to the situation in which Jews found themselves during WWII.

As Delfi journalists put it, Loss’s words “really blew up the Estonian community.”

“In my post, I shared my concerns about the rampant Russophobia in Estonia, citing as an example what happened to the Jews before WWII. It also started with ‘innocent’ discriminatory measures to end up in a catastrophe: a whole nation was blamed for all kinds of sins based on their ethnicity, which later led to heinous crimes,” Loss says explaining his point to me.

Filipp Loss, art director of the Russian Theatre in Tallinn. Photo by Vladislava Snurnikova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

The post triggered heated debates in Estonian media, but the art director was supported mainly by Russian-speaking residents of the country. He says some of them have even stopped and thanked him in the street.

“It’s obvious that the problem of discrimination against Russian citizens should be discussed publicly, as this affects the interests of a substantial part of Estonian society and runs counter to the spirit of freedom, democracy, and friendship between nations,” says Loss.

Even though the Russian Theatre’s art director tried to explain in interviews that followed up that he did not mean to draw direct parallels between the Holocaust and visa restrictions, most Estonians felt deeply insulted. European parliamentarian Urmas Paet demanded that Loss’s “job contract and residence permit be annulled immediately.” The Estonian Directors and Dramaturgs Union (EDDU) expelled Loss, saying that his statement “denigrates the Estonian nation, state, and culture.”

Loss’s contract as the Russian Theatre’s art director was to expire on 5 September, and it was not extended. The theatre’s director, Svetlana Jantsek, took over the job temporarily, while Loss was supposed to stay in the theatre as stage director.

However, on September 12, Jantsek terminated that contract with him, as well.

“She decided that she had the right to sack me based on that Facebook post. She wrote that I had undermined the Russian Theatre’s reputation and even put its very existence at risk. That said, members of the theatre’s board did not consider it necessary to apply repressive measures to me, and so that was her personal decision,” Loss says.

The former art director is determined to go to court to demand his reinstatement in his favourite job. He is not planning to leave Estonia.

“Something done by a particular person cannot change my attitude toward my colleagues from the Russian Theatre and the entire theatrical community of Estonia, a country that I love and where I’d like to live,” he says.

Shortly before those dramatic events, I had been to Loss’s office at the Russian Theatre. While he did not compare Estonia to Nazi Germany during our conversation, he still spoke quite harshly.

“Rejecting everything related to Russia, breaking up all cultural, scientific, educational, and other ties (which Estonia, as well as the other Baltic states, did at the very start of the war — author’s note) looks absolutely unproductive to me. What’s more, it actually contributes to the Putin regime’s unbridled aggression rather than opposes it. This only foments tension, fear, and enmity. This only fuels aggression, which all of us want to resist,” says Loss, a big and amiably-looking man.

The state-run Russian Theatre had not experienced pressure from the Estonian government before the end of the summer.

“Fortunately, nobody seriously tried to make us remove the word Russian from our name (something that happened in Lithuania — author’s note). Our theatre hosted a traditional theatrical festival on World Theatre Day, and even though some had proposed that the venue be changed, the majority of Estonia’s theatrical community said no. We had the Estonian president and parliamentarians here, all of them were happy, and all came together. After all, we see ourselves as part of Estonia and jointly oppose the aggression,” Loss said.

There has been no talk about ending the government financing of the Russian Theatre, not to mention shutting it down.

“I think this would be utterly absurd, for our theatre is one of those bridges that link Russian and Estonian cultures, and it serves as a guarantor of peace and accord in society,” Loss said.

“So it turns out these bridges are no longer necessary?” I ask him.

“You just can’t move one-third of the Estonian population somewhere overnight. These people feel like a part of this country, but it’s a Russian part, and you can’t just issue a decree and forbid these people to be Russian,” he says.

“But you can shut down the theatre.”

“You can. You can also forbid people to speak in Russian and strip them of their citizenship for that. There are no boundaries to idiocy. But you should be aware why you do something.”

Of course, Loss complains about ruptures of cultural ties with Russia.

“We were confronted with the fact that the agreement on cultural cooperation between Estonia and Russia has been severed for three years, but the Estonian theatrical community is deeply rooted in Russia. Many people who are seen as cultural icons here studied in Russia and collaborated with Russian theatres. Numerous actors have regularly come here, and the entire Estonian elite has always been eager to attend Golden Mask guest performances. Tours, festivals — all of this became unwanted immediately.”

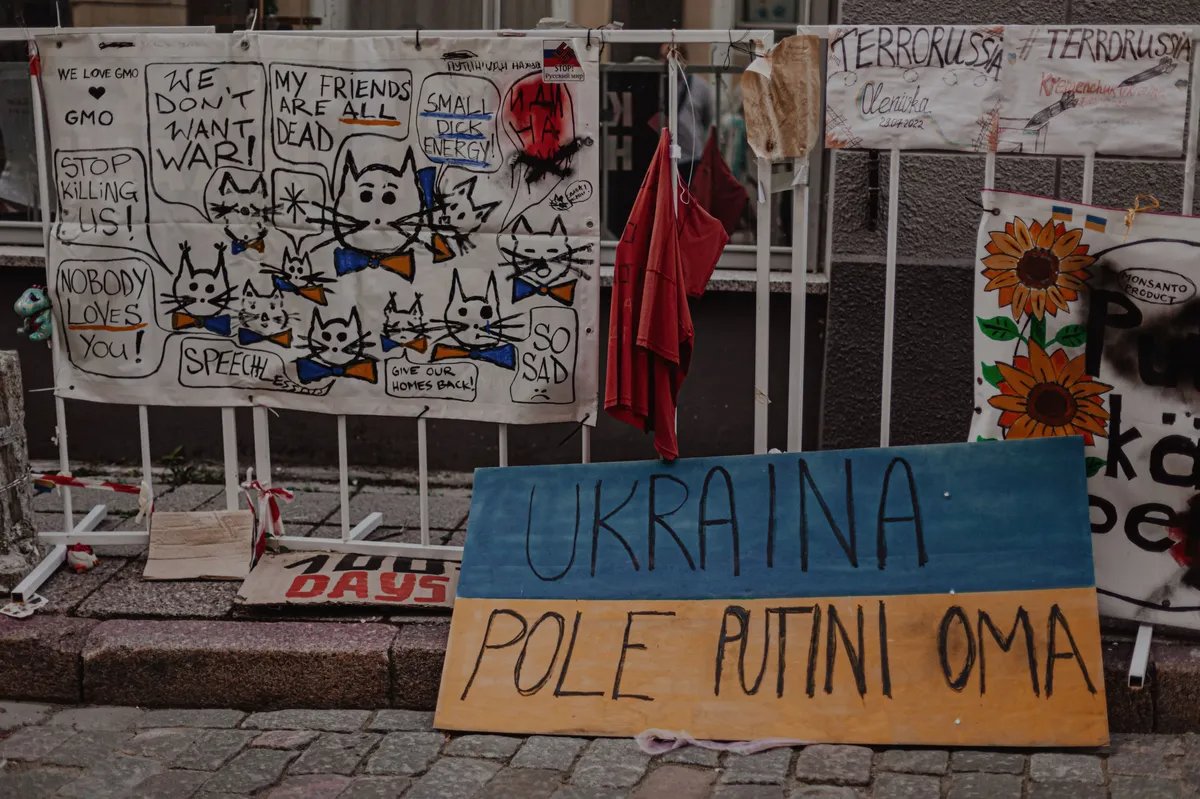

Posters in support of Ukraine in Tallinn. Photo by Vladislava Snurnikova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

For instance, the playwright Vyacheslav Durnenkov was supposed to come from Russia to work full-time at the Russian Theatre this coming winter, but alas.

“I cannot invite a stage director or an actor from Russia for purely legal reasons now, although I believe there should be exemptions. After all, in the current situation, it’s very important to take into account this person’s civic position, their attitude toward the war, and their interrelations with Putin’s government. For many excellent and honest people, working abroad is the only opportunity to survive nowadays,” complains Loss.

What matters even more, in his words, is not particular persons but the state’s strategy.

“What many view as deterrence of Russia is pointless, in my opinion. This breaks up the few ties that still exist between Russia and Europe, between Russian and European culture. The people who are imposing all these sanctions steer in the same direction as Putin does, namely toward isolating Russia. Virtually any move made by the Estonian authorities automatically gets in the crosshairs of Putin’s propaganda.

Didn’t they ever think why anything they do plays into the hands of Putin and his entourage? Why help Putin sail toward outright tyranny?”

He maintains that the local elites expect to score political points to win the next elections “by showing what strong politicians they are and how much tougher they are than the rest of Europe in countering Russia’s aggression.” The art director does not justify the war and describes the Russian army’s actions as monstrous, and yet he is sure that Putin’s goal is “a total break-up with the European civilisation,” and Estonia is helping him to achieve it, which is “wrong, preposterous, and harmful.”

Loss points out that one-third of the Estonian population speaks in Russian, and these people are as legitimate Estonian residents as all the others, many of whom have been living here for generations.

“Why insult them and live in fear, thinking all the time what those Russians might be up to tomorrow? Wouldn’t it be better to communicate with those people as much as possible, try to understand and take into consideration their sentiments? Isn’t it a more farsighted policy? If this idiot (Putin — author’s note) uses a nuclear weapon tomorrow, it’s curtains for us. And if [the Estonian authorities] think that what they’re doing can avert this threat, they’re sadly mistaken,” he says.

What is interesting is that virtually all government buildings in the Baltic countries have displayed Ukrainian flags, but there are none on the Russian Theatre.

“Some might criticise you for not supporting Ukraine enough,” I tell the art director.

“We are the Russian Theatre, but this is not a reason for us to display a Russian flag. But if someone thinks that they can stop the war by hoisting a Ukrainian flag, they’re also deluded. If you want to fight for the good cause, take up arms and go fighting. If you want to help, find those who are in trouble and help them. I have refugees from Ukraine living in my apartment now. I want the bloodshed, killings, and mutual hatred to stop as soon as possible. I understand that this is mostly utopian, but I am for peace,” Loss answers.

He has been working in Estonia for the sixth year and does not want to return to Russia.

“I left Russia because I wanted to live and work in Estonia. I recently travelled to Moscow and met my relatives and friends, but my home is here. I sincerely share Estonia’s interests. I wish this country all well. It’s not that I fall asleep and wake up thinking about Russia, but I am concerned about Russians living here. They are my spectators and my compatriots,” says Loss.

Studying for nothing

Adam Alidibirov, a student of the Narva College of the University of Tartu, does not care either about the Soviet tank or the Russian Theatre and is concerned about quite different problems.

“I learned that this tank existed only after all of this started. It doesn’t mean anything to me personally. I don’t care if they’ve removed it,” he says.

Alidibirov came to Estonia from Chechnya two years ago to study and qualify as an IT specialist.

“My goal was to leave Chechnya for any other place. And not Russia, because they’ll find you there. Estonia had a program under which you had to learn the Estonian language for one year for free and then study IT. Naturally, I thought this was a cool opportunity, and so I was interviewed, passed tests, and was admitted,” he says.

Immediately after the Ukraine war started, the University of Tartu (to which the Narva College belongs), as well as other Estonian universities and colleges, refused to admit students from Russia. Alidibirov and other students were assured at the time that this measure would not apply to them, but the war was continuing, and the Baltic countries began coming up with more ideas as to how to oppose Russians. In August, the Estonian government decided not only to stop issuing residence permits to Russians, but also to stop extending the valid ones.

Adam Alidibirov, a Narva College student. Photo by Vladislava Snurnikova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

This directly affected about 80 Russian and Belarusian students of the Narva College, because Estonia normally grants a standard student residence permit for three years (as the term of study), but most of those students had to spend the first year of their stay in Estonia to learn the official language.

The decision came as a complete surprise to Alidibirov.

“I didn’t expect that they would [make the decision] based solely on nationality. I thought they’d see what kind of a person it is. If someone supports the war and draws Z, that’s quite understandable,” he says.

Alidibirov said he did not know a single student campaigning for or even supporting the war. On the contrary, many have volunteered to help Ukrainian refugees in Narva.

The University of Tartu declined to help its students, and so they appealed to the television and printed media and launched a petition. It took them only one day to collect enough signatures in support for their petition to make it obligatory for the parliament to consider it. This prompted the authorities to review their decision and allow those already staying in Estonia to complete their studies, but they would still have to leave the country after completing it.

Alidibirov reasons that this decision does not help either Estonia or Ukraine in any way.

“This is absolutely illogical and pointless. When we applied to study here, one of the selection criteria was our desire to stay in Estonia and apply knowledge we gain here. In the end, they’ve enrolled students, taught them for four years, and now they’re sending them back!” he says in surprise.

“But the war broke out,” I say.

“True, you can say that this explains it, but how reasonable is this decision? I am not saying that [the Estonian authorities] are bad. But knowing that I’ve wasted two years is frustrating. I understand there are people whose situations are even worse, and I don’t demand anything.

If they don’t change this decision, I’ll have to move to another country, but it took me a year and a half here to start standing on my own feet,” he complains.

Alidibirov says he feels absolutely at home in Estonia now, although seeing how uncomfortable he feels being interviewed by a journalist, it is clear to me that it was quite hard to do for a Chechen. During his first year in Estonia, he travelled to live in Tallinn and Tartu, as Narva is the wrong place to get immersed in an Estonian language environment.

“I am learning not only the language, but also literature and films, like, for instance November. I immerse myself in Estonian culture not because I am being forced to or because I need this but because I am interested,” the young Chechen says.

He even customised his web browser to be able to highlight any Estonian word and see immediately how it is inflected for case and how it is used.

Alidibirov says he personally has not experienced discrimination in Estonia. On the contrary, everyone praises his attempts to speak in Estonian.

“Perhaps the attitudes toward local Russians are such here because they don’t learn the Estonian language and don’t try to integrate into society,” he reasons.

Photo by Vladislava Snurnikova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

I ask Alidibirov whether he feels any guilt for what is happening in Ukraine and what he thinks about collective responsibility.

“I don’t feel any guilt, that’s what I can say for sure. I grew up in Chechnya during the war started by Russia. As soon as I reached voting age, I left, and therefore, I didn’t vote in elections and didn’t attend rallies. Therefore, I think I have nothing to be blamed for. It’s the people making decisions who are to blame,” Alidibirov says, admitting at the same time that he does bear some responsibility, as well as all those who have a Russian passport.

Filipp Loss, former art director of the Russian Theatre in Tallinn, also says he does not think he should feel ashamed for being Russian.

“While I am a Russian Jew, and now already an Estonian Jew, I feel absolutely no desire to abandon my Russianness. This would be absolutely unnatural and absurd for me. This would mean losing myself,” Loss says.

He says he understands and does not condemn people who feel ashamed, describing this feeling as their protective response.

“I sympathise with the people who find it emotionally hard to admit that their country is an aggressor. I am also really unhappy about it, but at the biological level, this doesn’t make me feel overwhelmingly ashamed and doesn’t prompt me to cut off and discard anything that links me with Russia,” he says.

On the other hand, he says seeing what numerous European policymakers chiefly do makes him feel “a natural desire to defend my Russianness.”

“I feel pain for my country, but I also feel pain when someone tries to humiliate it. Perhaps the Russian world idea is hopelessly discredited for long, but I am absolutely unwilling to get rid of my Russianness. Russia’s history has lots of pages I keep being proud of. And the war against Ukraine is just a disgraceful episode, and there’ve been quite a few disgraceful episodes in Russia’s history,” Loss said.

Photo by Vladislava Snurnikova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

Doctoral students, go home!

Adam Alidibirov is particularly perplexed by Estonia’s intention to expel even students trained to teach the Estonian language.

“There is a huge shortage of teachers in Ida-Virumaa (the county where Narva is located and which is inhabited chiefly by ethnic Russians — author’s note) as it is, and now they’re also kicking out those whom they’ve trained for three years. I just can’t understand where else in the world teachers of the Estonian language are in demand, apart from Estonia itself,” says Alidibirov.

The same concerns medical doctors, who have come from Russia and learned Estonian but who are being sent back now.

Polina Oskolskaya, a doctoral student at the University of Tartu’s Institute of Estonian and General Linguistics, also wonders where else teachers of Estonian might be needed. She specialises in Finno-Ugric culture, and all her life in Russia was related to the Estonian language.

“I learned it in Russia, and I taught it in Russia, too,” she says.

There were two or three teachers of the Estonian language per five million people living in St. Petersburg at the time, she says.

Since last year, Oskolskaya has been studying in Tartu, writing longreads on specifics of the Estonian version of Russian, and running a Telegram channel.

“I have a residence permit as a doctoral student. People completing their masters’ or doctoral programs earlier tried to find a job in Estonia, but now they won’t have this opportunity,” she says sadly.

“Moreover, even though they allowed such students to complete their courses, they might change their mind, as well,” I note.

“That’s true, and that’s why I don’t feel confident. I have no feeling that I can stay here writing my doctoral thesis for another two years and not be worried about anything.”

Irina Belobrovtseva, doctor of philology and professor of Russian literature at Tallinn University’s Institute of Slavonic Languages and Cultures, says that, when the decision was being made to stop admitting applicants from Russia and Belarus, only the rector of Tallinn University spoke against it.

“Two artistic schools, the Academy of Arts and the Academy of Music and Theatre, thought an exception would be made for them, as each of their students is a rarity, but it turned out later that all must comply, and even the private Mainor Business School had to refuse the students they had already admitted,” she says.

Irina Belobrovtseva, professor of Russian literature at Tallinn University's Institute of Slavonic Languages and Cultures. Photo by Vladislava Snurnikova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

Oskolskaya and Alexandra Milyakina from the Chair of Semiotics at the University of Tartu in March launched a petition against the decision not to admit students and doctoral students with Russian passports. The ladies say it was signed by about 2,000 people, including some Estonian professors.

“Anyway, we were criticised for having mostly Russian names on the list. Pro-rectors from the University of Tartu spoke in the media from time to time to say that the petition didn’t mean anything as it didn’t represent the university’s position,” Milyakina says. “Then they arranged a Zoom conference with pro-rectors for semiotics and philosophy specialists, and for most of its time, we were shown a presentation on cyberwarfare and lectured on how easy it is to become its target and how not very smart and intelligent university employees and students become a tool in it.

Then the petition was also scrutinized for possible links to Russian propaganda because of a bot attack on the University of Tartu’s social networks.”

As Belobrovtseva sees it, there are mixed feelings in Estonian society about the government’s decision not to admit students from Russia.

“Certainly, the decision is inappropriate, but nobody can do anything about it, and no matter what we think about it, this can’t influence the situation in any way. Our prime minister has declared officially that our worldview should be black-and-white. Take, for instance, Marko Mihkelson, head of the Foreign Affairs Committee at the Estonian parliament, who doesn’t see any problem in this situation, telling me that he had met a Russian graduate of Oxford University 20 years ago, who proved to be ‘a pure Stalinist’.”

Polina Oskolskaya, a doctoral student at the University of Tartu's Institute of Estonian and General Linguistics, and Alexandra Milyakina, an employee of the Chair of Semiotics at the University of Tartu. Photo by Vladislava Snurnikova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

At the University of Tartu, only 218 of the roughly 13,000 students are Russians, although there were 359 of them last year, and this number had been growing steadily.

“We don’t really have too many foreign students, because there are only 30 programs where people not knowing Estonian can apply,” Oskolskaya says.

Milyakina says the decision has actually affected many people, as everyone she knows in Russia is considering precisely an academic path of emigration. In her view, the Estonian authorities have decided to apply this measure to show that they do at least something and at the same time not to affect too many people.

“But this doesn’t mean that those people deserved this,” Oskolskaya says.

She admits that she did not expect Estonia to protect her and understands why it is acting this way, and yet she wants these measures to be more “merciful.”

“I’ve been speaking out against the Ukraine war for half a year, and I’ve been doing this pretty openly, too. This includes speaking in the media and at rallies, financially supporting organisations banned in Russia, and helping refugees. If I were expelled to Russia now, this would be very dangerous for me. I agree to feel responsibility [for the war], but perhaps I’d better sponsor refugees than be put in jail in Russia,” Oskolskaya says.

This policy has also affected members of Finno-Ugric ethnic groups, who live in Russia and whom Estonia has always supported actively, she says.

“Such ethnic groups as Mordva or Komi — all of them are Russian citizens, we love and study their language and culture, but they are now denied entry, and all cultural ties are banned,” Oskolskaya says emotionally, also mentioning those who have bought real estate in Estonia, which they cannot even sell now.

That said, Oskolskaya and Milyakina also like it very much to be in Estonia.

“I don’t feel any hatred or rejection here. Particularly in Estonia, there have been periods of mutual tension between Russians and Estonians following the Soviet Union’s breakup, when, as locals say, [Russians] might’ve been kicked out of a bus. Everything has changed very much over these thirty years, and now, when an article about my story was published, there were comments like ‘Couldn’t you really make an exception? Perhaps you might grant citizenship to this person?’” Oskolskaya says. “But I understand that Estonia is a small country bordering a very big one armed with nuclear weapons. At the start of the war, everyone here, including me, was scared and everyone feared that something similar might also be started here.”

Milyakina says that, as an LGBT person, her return to Russia would be “an untoward option.” Her wife has already received an Estonian passport, but she herself has been waiting for about a year for Russia to agree to annul her citizenship.

Aimar Ventsel, professor of ethnology from the University of Tartu, a bald-headed Estonian with tattoos, has frequently visited Russia in the past, and now he stands ready to support the decision to ban Russian students from studying in Estonia.

“If you look at this as some symbolic sanction, there is a positive aspect here. This makes it understood: sorry, but your country is committing a crime. I taught at Russian colleges in Siberia and gave a couple of lectures in St. Petersburg, and I disagree that all Russian students are opposition activists. There are those who favour Putin, there are those who are opposed to him, and there are those who don’t care,” he says.

Aimar Ventsel, professor of ethnology at the Tartu University. Photo by Vladislava Snurnikova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

Estonia has imposed the ban “with fanfare,” while, for instance, Scandinavian countries have forbidden sending emails to Russia from university accounts or defending their doctoral theses based on materials gathered in Russia, but none of this has gained such publicity, Ventsel says (I was unable to find confirmation to this — author’s note).

“But doesn’t it matter that people come here to study and learn something new? If they study only in Russia, nobody will ever change anything there,” I point out.

“But there is a moral responsibility factor. It’s your state and it’s your president. After all, all of this has been continuing since 2014, and the Russians have elected this government themselves.”

“But what if people didn’t vote for Putin? Don’t you know that elections [in Russia] are routinely falsified? If you show a ballot with a tick against Putin, will you be allowed to study?”

“I’ve been thinking about this regularly since February. And it’s not a black-and-white situation, but how would you sort good Russians from not that good ones? I’ve seen a proposal that this could be done based on a selfie from a police van, but it’s easier to refuse them all for the time being,” the professor replies.

Asked whether he thinks that any university is interested in having talented students, including those from Russia, Ventsel replies that numerous Estonian businesspeople have voluntarily phased out cooperation with Russian companies.

“A university is also a business in some respect, which sells education and promotes itself owing to having talented employees.

A friend of my dealing with construction materials has said he won’t buy anything from Russia. And similarly, universities won’t use talents from Russia on principle,” Ventsel says.

Visas as a privilege

It seems it was Estonia, namely its Prime Minister Kaja Kallas, who started the debate back in early August as to whether the European Union should stop issuing tourist visas to Russians. The Baltic countries have discontinued doing so since the second day of the war, but, at Kallas’s behest, the visa discussion came to the foreground for nearly a month even amid the war. “Stop issuing tourist visas to Russians. Visiting Europe is a privilege, not a human right,” Kallas wrote on Twitter.

The result is: the Baltic countries have stopped admitting Russians with ordinary Schengen visas issued by any country since 19 September. In addition, Baltic politicians have repeatedly explained this measure as follows: let Russian citizens topple Putin at home rather than vacate at European resorts.

Marko Mihkelson, who chairs the Foreign Affairs Committee at the Estonian parliament, meets me at his office wearing shorts (he has a day off) and invites me to sit down where a Russian ambassador once sat.

“Is this a good comparison?” I ask him.

“No, not at all,” Mihkelson replies sombrely. He worked as a reporter of Postimees in Moscow in the 1990s, and by all appearances, he did not fall in love with the city at the time. “I am sure there are lots of people in Russia who are opposed to the war and genocide in Ukraine. However, there are lots of others who fervently support this. We see numerous videos on social media on which Russian tourists behave very inappropriately,” he says.

Marko Mihkelson, head of the Foreign Affairs Committee of the Estonian parliament. Photo by Vladislava Snurnikova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

He approves of the idea to bar Russian tourists from entering the European Union, “because Russians should understand that the war that is ongoing will affect their personal lives, because all of them bear responsibility for it.”

The lawmaker says that nobody would put obstacles to those who need a humanitarian visa to remain free or even alive, and yet he makes this reservation:

“I’d like Russians to be as energetic and vigorous [as they are regarding Schengen visas] in trying to change something or say something against the war every day and every hour, but I don’t see any of that.”

“But they get fined and then jailed for that,” I point out to Mihkelson.

“Yes, it’s a totalitarian state, and it’s clear that it’s hard for ordinary people to do something overnight. But when Kommersant asks its readers whether they support a new offensive on Kyiv and sixty percent say yes, what does it mean? It’s pure fascism in Russia now, as [historian] Timothy Snyder describes contemporary Russia in his interview to Mikhail Zygar. This is not just some minor conflict but a war comparable to a global one. The entry ban is one of those measures that should make people think what’s going on and what kind of future they want to live in,” reiterates Mihkelson.

Yaroslav Varenik, a journalist from the Arkhangelsk-based publication 29.ru, is one of those who fell victim to the new visa policy. In the early hours of August 14, he was first subjected to a humiliating interrogation by Russian border guards (he had been searched some time before as part of an investigation of the Anti-Corruption Foundation), after which Estonian border guards barred him from entering their country, and what is more, annulled his Schengen visa.

“I disagree with the European Union’s policy,” the journalist tells me. “It’s hypocritical on the part of European politicians, because they’ve been sponsoring the Putin regime for years by buying oil and gas from it.

To shift the blame, they scapegoat activists, journalists, and actually all Russians. By doing so, they distract the attention of their own citizens.”

Mihkelson agrees with Varenik on this, saying that Estonia has long been trying to persuade its European Union fellows to stop buying oil and gas from Russia.

“It’s clear that Russia takes advantage of supplying [commodities] to Europe to attain its foreign policy goals. We realised this many years ago, but unfortunately, we weren’t heard. And lots of our friends in Europe admit now that they used to think we were simply paranoid because of the complicated history of our relations with Russia,” he says.

Varenik is sure that Baltic politicians would not attain the declared goals through imposing an entry ban, as Russians can still travel to Europe through other countries.

“And besides, a typical Russian tourist is a well-to-do person with a family, who is unlikely to risk their business or freedom by joining protests, which Europeans are seeking to prompt them to do,” Varenik said.

The authorities of the Baltic countries keep clarifying that the entry ban does not apply to those who have humanitarian visas or to opposition activists and journalists who suffer from persecutions at home. However, it is quite hard for a typical activist to receive a humanitarian visa, and many flee to Europe precisely with tourist visas. Varenik, a journalist from Arkhangelsk, was not planning to flee Russia but simply wanted to spend a weekend walking around Tallinn and “taking a closer look if I’d still have to leave.” Obviously, the annulment of his visa and the entry ban imposed on him did not make him more confident about his future.

Tallinn. Photo by Vladislava Snurnikova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

When Estonia decided to stop admitting Russians with Estonian Schengen visas, European parliamentarian Yana Toom described this step as “feebleminded.”

“Okay, we’re saying that Russians don’t oppose Putin resolutely enough, and if all of them are locked there, they’ll topple him. But, firstly, protest does exist in Russia, and it is quite significant, too. I have numerous friends whose children have been thrown into a police van a hundred times. And we’re telling them that they are a piece of shit because they failed to topple Putin, aren’t we? What is it? And secondly, who is saying that? Estonians, who tolerated [the Soviet] occupation for 70 years without saying a word! Dissidents [of that era in Estonia] can be counted on one hand,” Toom says, recalling that Prime Minister Kallas’s father was also a prominent Soviet official.

Historian David Vseviov assures me, however, that the Estonian authorities will eventually find out whom to issue humanitarian visas and whom not.

“You need to give asylum to those who are entitled to it. And you should stop others from travelling to Paris for luxury bags,” Vseviov says. He also mentions the reason why the Baltic countries can easily afford this ban:

“Ninety percent of Russian tourists use Estonia solely to enter the Schengen zone, that is, we have no economic profit from this but only bear a moral burden.”

Vseviov admits that nobody forced German migrants of Jewish descent to return to Berlin and topple Hitler in 1939, but he recalls that Estonians, just like opposition-minded Russians nowadays, were also hostages to the USSR.

“You can’t do anything about that. Don’t look for someone to blame elsewhere once you started this mess yourself. After February 24, nobody knows for certain what’s right and what’s wrong here. Someone is robbing someone, and shall we say that nothing will help? Something needs to be done, after all,” he says.

“Perhaps the Estonian government wants to do at least something?” I recall Vseviov’s words during my conversation with Toom.

“You can’t sanction whole nations. You can do that with respect to regimes, businesses, individuals, or companies, or even social groups, but not to all. And besides, what’s the point, considering that 76% of Russians don’t have a foreign travel passport, and half of them never leave even their province. Whom are we punishing this way?”

Toom has to give some attention to her grandchildren: the elder sister has just hit her younger brother with a plastic stick, and the latter starts crying.

“Kids, you’re barbarians. Come over here, I’ll pity you,” Yana tells the boy. “You’re a moose, not a sister! We’ll go to the spa when I finish the conversation, and if you don’t hit your brother, I’ll finish it earlier. Look, my grandson is hitting the toy horse with his stick for absolutely the same reasons,” she continues to answer my question. “He has to do something, and perhaps he even concluded with his little brain that, if he keeps whacking the toy horse with his stick, he’ll go to the spa sooner. But a politician can’t behave that way, after all. And yet this is actually how a lot of things are done in Estonia. The same happens to gas bills here. Indeed, as a result of the sanctions, the gas prices skyrocketed, and it just so happened that, having sold less gas, Putin got more money. But it’s something we don’t like to talk about because it’s very unpleasant. All of this is like some theatre of the absurd.”

In defense of activists

Unlike Yaroslav Varenik, Russian activist Yevgenia Chirikova had no problems entering Estonia, as she had arrived here back in 2015.

“Crimea’s annexation came as a huge blow to me. I didn’t expect that [Russian people] would support that so enthusiastically,” Chirikova says, explaining why she decided to leave the country. “It might look naïve, but I was sure that the whole nation would stand up and win, because Russians would not accept the violation of an international convention. Then started this ugly propagandistic campaign for war, and I felt physically disgusting to be amidst all of that.”

Yevgenia Chirikova, a Russian activist and human rights campaigner. Photo by Vladislava Snurnikova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

Anyway, Chirikova attributes her decision chiefly to her desire “to develop as a civic activist.” While in Russia, she was known as the organiser of a campaign in defence of the Khimki Forest. She was later elected to the Opposition Coordination Council and founded the Activatica website dealing with all forms of activism in Russia and other countries.

“I saw it as my mission to help civil society, and I realised that I wouldn’t be allowed to do that if I stay in Russia. I also understood that my taxes finance the war mongering campaign, and that’s why I decided to evacuate,” Chirikova said.

She chose Estonia because “this is an ideal place to help Russian civil society,” and she keeps doing this now, as well.

“We have managed to build a large network of activists both in Europe and in Russia. My situation is the following: I am here physically, but I am still there mentally. My mornings begin with reading news from Russia, and I am always in touch with Russian activists, because I am in charge of evacuation programs. I believe this is exactly a force that will build a perfect democratic Russia of the future when the regime falls, as these people are firmly committed to democracy, and they know what it is like and why it is necessary,” she said.

Since the start of the war, Chirikova and her colleagues have been helping Russian activists and Ukrainian refugees flee to Europe via Narva.

“The Activatica web portal saw its mission as supporting civic activists all over the country, whose interests varied from renovation to environment protection, but with the start of the war, all of them have virtually forgotten about themselves and are helping Ukrainian refugees stranded in Russia. We have three shelters in different countries, and Russian activists work in all of them. It seems to me that this is really cool. We show that it’s an absolute lie that all Russians have elected the Putin regime and that all of them support it,” she says.

Chirikova sees the ban on entering Estonia with Schengen visas as an obstacle to her work, but she believes all the blame for this should rest exclusively with far-right Estonian politicians.

“In order to be liked by their rightist voters, they seek to lobby legislation barring Russians from entering Estonian territory. I know that a hundred percent of [Russian] civic activists facing criminal charges for anti-war activities at home who have been granted protection and refugee status in Europe had entered with tourist visas, because it’s virtually impossible to receive a humanitarian visa. I know that, for I tried to get it myself,” Chirikova said.

Now she has to evacuate activists to Bishkek, Almaty, and sometimes to Georgia, where some of them have been denied entry recently.

“Dozens of civic activists opposing the Putin regime are waiting for help. They have every reason to enjoy international protection. Once an ordinary activist whom nobody would defend is put in jail, anything can happen to them. These are people I am worried about most of all,” Chirikova says.

The campaign against Russians launched by right-wing Estonian politicians has even overshadowed the issue of Ukrainian refugees, she says.

“We’ve had problems with Ukrainian refugees whom Estonian border guards didn’t allow into the country for some reason, and those cases really deserve more attention, because the debates about the tank and visas won’t help Ukraine win, while they divide society very much. Putin’s media have already taken advantage of this to tell Russians once again that they are hated in Europe,” she says.

Photo by Vladislava Snurnikova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

Chirikova proposed selling the Narva tank at an auction as a piece of art and using the money to buy a Bayraktar drone for the Ukrainian Armed Forces.

She refuses to share collective responsibility, arguing that she did all she could back in 2012, when she set up a tent on Red Square and called for dismantling the Putin regime.

“I perfectly remember how I fought the Nord Stream 2 project for eight years. Estonian politician Marianne Mikko and I urged German policymakers to decline that project, but they wouldn’t listen to us. Why should those who warned about the danger of collaboration with Putin now fully bear the blame for the fact that he still isn’t gone? And what about those who pumped money into that regime for years — shouldn’t they? I think the question of who is to blame sidetracks us and doesn’t help those Ukrainians who are dying under Putin’s bombs,” Chirikova says.

She has visited the Estonian Foreign Ministry to explain all of her reasons, after which she was assured that nobody would be deported from Estonia.

“As a matter of fact, Estonians are not that categorical at all, they’re very humane, and you can always reach a consensus with them. My seven-year experience shows that local officials have human faces, and I do believe a dialogue is possible,” Chirikova says optimistically. “Estonians should come to understand us now at some genetic level. After all, they’ve been through occupation, and the Putin regime to me is like occupation, as well.”

However, there is little hope for this, as even people like Aimar Ventsel, the progressive professor at the University of Tartu, admits that he has no firm position on visas.

“I have friends and colleagues in Russia. For instance, Russian punks who are deeply integrated into the Western punk community and often perform in Estonia, have always been opposed to Putin’s politics. I know their convictions, and therefore, I don’t think they need to be cut off from Europe, but I’ll tell you frankly that I don’t care about people whom I don’t know. Indeed, I am aware of the reason that this is a way for opposition members to come to Europe because they are in danger at home, but when I read discussions about this, I am really happy that I don’t have to decide,” Ventsel says.

It should also be noted that Ventsel has no clear position as to whether Soviet monuments should be dismantled.

“I am not really a big fan of the demolition of monuments, but the situation is so heated now that, if there were a referendum, I’d speak in favour of removing the tank, because thirty years is enough to be fed up with that stuff,” he says.

Polis Narva

“For Estonians, the tank is a symbol of occupation. For many Russians, it’s certainly a symbol of liberation from Nazism. People are afraid that, once they sort out the monument problem, they’ll eventually get at us. And there is actually some point here,” Yana Toom argues.

She notes that the 100,000 Russian citizens living in Estonia are feeling extremely uncomfortable now. Estonian media call them “a threat to national security.”

“If we are in a state of war, this means that there are 100,000 citizens of the aggressor state in Estonia. Obviously, there is some plan as to what to do to them, but nobody knows anything about it. This is why such fantasies appear,” she says.

Photo by Vladislava Snurnikova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

Ethnic Russians in Estonia do not feel happy about “the visa thing,” as Toom put it.

“Not because everyone cares about Russian tourists, but because all of us have families or friends in Russia. My sister lives in Lipetsk, and to my invitation to come to me, she replied, ‘You’re not a relative to me’. The website of our embassy says that parents are relatives, but a sister is not. Russia did not let my sister travel to Estonia to attend our father’s funeral, because she was a public servant, and now that she has retired, Estonia tells her, a sixty-year-old woman with cancer, that she must topple Putin. This is kind of unpleasant,” Toom says with her unmatched sarcasm.

She reminds me that Estonians have never viewed Narva as a full-fledged part of the country.

“In the 1990s, there were attempts to hold a referendum here to set up something like the Donbas republics. This was eventually settled, but Narva was looked askance at for years. Over the past ten years or so, efforts have been made to promote the so-called integration. They established the Estonian Language House and opened the VabaLava theatre centre here. The prime minister lived, worked, jogged, and spoke to locals in Russian here for a month. But now we are back where we were,” Toom says.

In Toom’s words, this did not make a great impression on the locals, because Estonians “view integration as something similar to assimilation, where you have not only to speak but also think in Estonian.”

Narva. Photo by Vladislava Snurnikova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

“But it’s actually a person’s right to speak in any language. If I pay taxes and don’t seek to be elected a parliamentarian, what’s the problem?” she wonders.

Here is how lawmaker Stalnuhhin expresses the opinion of Russian-speaking Narva residents about their treatment by Estonia.

“The Russians here don’t have any illusions anymore. We have a typical ancient Greek democracy with a parliament of sorts, where women, slaves, and those who are younger than 31 cannot make decisions. And there is also property qualification, and if you don’t have enough land or enough slaves, you have nothing to do in this parliament. Similarly, we have less than 9% of Russian-speaking voters, even though Russian speakers make up a quarter of the entire Estonian population,” Stalnuhhin says.

As Yana Toom explains to me, there are “citizens of two rates” in Estonia, and the second-rate people have no right to vote in parliamentary elections. Now some wish to deprive them also of the right to vote in local elections (which they were granted as a condition of Estonia’s accession to the EU). Stalnuhhin explains this by the desire to deprive the Centre Party of power in Tallinn, where this moderate force has been in office for years “mainly owing to this excessive constituency.”

Stalnuhhin knows Estonian as a second native language. He got his degree as a teacher of Estonian for a Russian school back in 1995 and has written several Estonian language textbooks.

“The Russians in Estonia have the perception that nobody would ask us anything. They’ll do anything they want with our education, and they’ll try to do anything they want with our memory. The constitution entitles me to choose a language of education for my child, but the state says that it is going to switch everything over to the Estonian language,” Stalnuhhin says angrily.

“But if we live in a democratic country and a person pays taxes, why should some of us decide that their children should receive an education in their native language and other children in a foreign one?

Turns out that, while some call themselves democrats, they are in fact downright totalitarianists.”

The legislator insists that a person should be able to choose a language in which to receive an education.

“As a Russian language teacher, I can tell you absolutely certainly that there are people particularly inclined to learn foreign languages, there is a general mass of 70% who need to practice the language all the time so as not to forget it, and there are also 10% of monolingual people who can’t be taught a foreign language. I’ve taught about 2,500 people in this town, and I know this,” Stalnuhhin says. “By making the Estonian language obligatory for all, you simply deprive a substantial number of people of the opportunity to get a higher education and build a career.”

He insists that this is actually one of the goals of the education policy pursued in Estonia.

“The Russians must be kept down, for they are necessary only as street cleaners and bus drivers,” he says.

According to Stalnuhhin, the Estonian government has not bothered even to make proper textbooks over the past 30 years.

“Let me put it in layman’s terms. If you study the Estonian language, you’ll see that it has a special declension and conjugation system, and in order to get the right words in all forms, you have to know several forms. Only one dictionary in Estonia published since 1985 contains all those forms,” says Stalnuhhin, who compiled the “correct” dictionary himself in 2012, which has never been officially approved by the Education Ministry.

Photo by Vladislava Snurnikova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

In Yana Toom’s words, the problem is that “however tiny the pool of Estonian language teachers is, they’ve dispersed it even more” lately.

“The level of knowledge of the Estonian language has declined rather than grown over the past several years. I made an inquiry with the ministry to find out that less than half of our Estonian language teachers at Russian schools are Estonian native speakers and received instruction in Estonian themselves,” she says in surprise.

Nevertheless, Estonia plans that the majority of schools shall switch to instruction in the Estonian language as early as in 2023.

“I’ve been telling my fellow lawmakers for twenty years: ‘You can do whatever you want, but let children and elderly people alone. Children as regards education and elderly people as regards historical memory’. But you should understand how appealing it is to a politician to make up a problem and solve it if you can’t cope with a real problem. This happens all over the world, and they’ve mastered this skill in Estonia,” Stalnuhhin concludes.

When I ask Yana Toom whether she believes Narva residents would welcome the Russian army if it suddenly invades Estonia, she flatly disagrees.

“All of us know what it’s like to be in Russia. After all, all of us have friends and relatives there. They have their own issues, and everyone who wanted to live in Russia already live there. There was quite a long period of time when real estate in Estonia was more expensive than, say, in Smolensk. Therefore, I don’t believe that, in case of Russian aggression, anyone would be happy here.”

She recalls coming to Narva at the start of the war together with Anton Alekseev, a reporter from Estonian television, to speak to locals and tell them that military aggression is a bad thing.

“You know, the room was full, but nobody tore us apart. They certainly argued with us, but it seems to me we basically managed to reach a consensus that, while Russians in Estonia do have problems and there is some discrimination here, we don’t want these problems to be resolved with bomb strikes. After all, everyone understands that, from a purely technical standpoint, you’ll have no chance to rejoice at this tiny piece of land where we are meeting now, considering the contemporary warfare methods. That’s as clear as day,” she says.

Russian prospects

Igor Rosenfeld, an elderly grey-haired man with a black moustache, runs the Kripta bookshop selling Russian books in Tartu. He graduated from the Russian literature department of the University of Tartu back in the Juri Lotman times. He opened his first shop in 1998 and has been in the book business since then. He says there are about 30,000 Russian-speaking people living in Tartu, but it is mostly children’s books that sell well.

Igor Rosenfeld, a book business owner in Tartu. Photo by Vladislava Snurnikova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

Before our conversation, he shows me three books he has written himself, one on Russian conservatism, another one, titled Third Marxism, “an attempt to formulate contemporary leftist ideology,” and also Estonia Before and After the Bronze Night. Rosenfeld is certain that military problems should not be extended to the humanitarian and educational field, but he declined to speak about this in detail until the Left Party of Estonia, in whose establishment he is involved, is registered officially.

As a Communist, he certainly is opposed to the removal of monuments.

“What does the Narva tank have to do with the military operation? The Russian government is not a Communist one, and the program of Russia’s Ukrainian campaign is in fact a whiteguard one, since it’s about a united and undivided Russia. But, for instance, they’ve also started speaking about removing the monument to Ernst Thalmann in Germany, as if Thalmann, an antifascist killed by the Nazis, were to blame for the Russian aggression. This is distorted logic,” says Rosenfeld, who maintains that “power in Ukraine belongs to radicals under whose leadership the country is behaving aggressively.”

Rosenfeld insists it was wrong “to provoke Russia with Maidan” and “cut Ukraine off it.”

“The philosophy of our right-wing radicals implies that Russia had to be countered. [Former Estonian Prime Minister] Mart Laar, for instance, published a booklet about the 20th Waffen-SS Division, was an advisor to [former Georgian President Mikheil] Saakashvili in 2008, and then dealt with the problem of Chechnya. That is, our people were in the vanguard of those who worked to weaken Russia in the 1990s. That’s why we have this situation now,” says Rosenfeld.

“But your shop hasn’t experienced any problems, even despite numerous books on Stalin present here, has it?”

“There’ve been no direct reprisals against me, and nobody has closed my shops. They let me work. After all, certain freedom of opinion does exist in Estonia, and even though there’s some censorship here, it’s not like that in the USSR,” Rosenfeld admits.

Most of Russians who have come to the Baltic countries lately are surprised at how widely the Russian language is used here. With the rare exception, you can hear Russian speech in stores, restaurants, and government institutions, and most of local websites have Russian versions.

“Estonia speaks in three languages, and this is true for both government institutions and business organisations. This is convenient to all except for a bunch of politicians who think they should highlight their efficiency before the Estonian share of their voters,” Loss says. “And if they think they can ban people from communicating in the Russian language in a snap, this is utterly naïve.”

In the view of Irina Belobrovtseva, doctor of philology, Russian schoolchildren going to Estonian schools “will retain the Russian language at the level spoken at home, and with the entire education system’s transition to the Estonian language, it’s hard to say what’s going to be left of their Russian.” However, she believes Russian will not die quickly in Estonia.

“Some five or six years ago, an Estonian children’s author was outraged to see the word ‘milk’ written in Russian on a carton, but such things still happen occasionally at the level of some hotheads. If there are Russian people who are unable to correctly understand information in Estonian, this information should also be available in Russian. Anyway, this is a matter of a couple of decades, after which our generation will become extinct,” says Belobrovtseva, who perfectly knows Estonian as well.

Future for everyone

Political scientist Karmo Tuur meets me at the counter of his beer shop Gambrinus in the very heart of the old part of Tartu. The selection of craft beer in his cellar is quite impressive.

“You can see by looking at me that I’ve been a beer fan since childhood,” Tuur grins into his fluffy moustache. “When I first walked into a special beer shop in Belgium, which we didn’t have at the time, I thought I should open something similar. I did this with the only goal in mind, so that not I should bring home beer but beer should come to me itself. That’s exactly what happened.”

Political scientist Karmo Tuur. Photo by Vladislava Snurnikova, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

Tuur has run his shop, standing from time to time at the counter himself, for about ten years now. In spare time, he comments on Estonia’s foreign policy. Tuur, who speaks Russian quite well, tells me that a number of excellent private breweries have lately emerged in Russia, and his shop occasionally used to offer Russian craft, as well, but “now it’s too toxic.”

“We are currently in the city of Tartu, which Russian troops have invaded 13 times, including twice when it was purposefully razed to the ground and its people were taken away under Ivan the Terrible and Peter the Great,” says Tuur.

“Do you believe there is the danger that this might happen again?”

“Such plans do exist, and the relevant agencies are thinking whom to invade to resolve Russia’s geopolitical problems. Countries like Latvia and Finland have been mentioned in this context, and the only question is when they take those plans off the shelf and put them on the table. Indeed, this danger does exist, and it’s quite realistic, too, but Moscow currently has some other things to worry about. We hope Ukraine would be able to postpone if not completely dash those projects.”

Tuur said he is sure a democratic Russia is possible in the future only if it breaks up into several states.

“There will still be people there who would moan and would like to restore the former greatness, but if they don’t win the majority and if a normal Pskov and Novgorod republic emerge, perhaps the imperial sentiment would vanish for some time. I have a friend, a professor, who has analysed all states in world history, calculated a breakup formula, and, applying it to Russia, got 2052.”

While the beer-loving political scientist is waiting for this date to come, lawmaker Mihkelson looks forward to a replay of the Nuremberg Trials — and of course, he expects this would happen sooner than that date.

“In the past hundred years, not a single hangman has been convicted, not a single decision to commit genocide or mass killings has been ruled a crime in Russia. And this is the main problem for Russia’s future. If you don’t address this, unfortunately, you can’t get out of this hole where the security men have driven Russia. It’s precisely this war that is a great chance for Russia to do that,” he says.

The Alexander Nevsky Cathedral is located right in front of the Estonian parliament building in Tallinn. Built in 1900, it is a vivid symbol of the Russian empire, which owned these lands starting from the 18th century. Mihkelson assures me that, unlike the Soviet tank monument, Estonia will not demolish this cathedral. However, the attitude toward the Soviet period in Estonia’s history still divides the Estonians and Russians living here.

Mihkelson insists that, after February 24, there can be no discussions on Soviet legacy, and all key monuments to Soviet occupation would be removed by the end of the year. Mihkelson’s fellow-parliamentarian Stalnuhhin says, when asked what he thinks about recognising the Soviet period as occupation:

“If I say yes, this would set me against my voters who don’t think so. If I say no, this would set the party against Estonian voters who think that there was occupation. Whenever Estonian journalists ask me such questions, I always answer this: ‘You’d better agree that Estonians were collaborationists, for how could it be that there was occupation but no collaborationism? Do you really mean all Estonians were forest brothers?”

Stalnuhhin says that, after the tank’s demolition, he has felt as if having been treated as an invader.

“I was born here, my mom was born here, and my grandma and grandpa were born here, too. You’re speaking of events that ended 30 years ago. Isn’t it enough to build a country anew? How long are they going to harp upon that? Show me a living invader who crossed the border in 1944 and is still holding some office. What are you talking about?”

“About memory! That’s what you like to talk about, isn’t it?”

“Was there occupation in the 18th century as well? Then you should tear down the monuments left from Peter the Great, like, for instance, the Kadriorg [Palace].”

“Well, they’ve torn down monuments to Columbus in America,” I note.

“This isn’t a good example for me. All of them are crazy morons there, and I don’t even want to talk about BLM. In Estonia, they’re fighting those who fought the Nazis. About 200,000 soldiers on the one side and 40,000 on the other died near Narva. Soil is soaked in blood here, and now they’re removing monuments. And who is doing that? Fighters of Nazis, really? Or maybe Nazis themselves?”

As Loss puts it, “it’s no good endlessly using the awful word ‘occupation’ to vindicate the authorities’ not very skilful actions toward the Russian-speaking population.”

Then the former Russian Theatre art director utters something like nearly a policy speech.

“Nothing should be justified by what happened yesterday. You should think about what happens today, or better about what’s going to happen tomorrow. I don’t like the extremes, I don’t like hatred. In the current political situation, the worst thing for me is the rupture of ties and trust between people, which have been developing for decades. I understand that I, as well as other people from the theatrical community, will have later to restore empathy, respect for another person’s standpoint, and the understanding that the world and people in it are very different. Everyone has their own truth, and everyone has their own pain. These are things that look obvious, but they are dismissed so easily when something causing fear comes. People can’t be blamed for being afraid of Russian invasion, and when I say that Estonian politicians act stupidly, I understand that their actions are prompted by fear. But fear is an ill adviser.”

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]