From the standpoint of ecclesiastical tradition, the story is unusual — but from moral and political standpoints, it seems understandable and even inevitable. On 6 September, Latvian president Egils Levits introduced in parliament amendments to the law about the Latvian Orthodox Church (LOC) — a law that caused quite a bit of controversy and was submitted for the consideration of the EU Court of Justice.

Latvia, following the tradition of its interwar government (1918-1940), adopted not one general law about freedom of conscience, but instead a handful of “denominational” laws. They secured for each specific religious organisation the rights to use a whole “denominational brand”: for example, there can exist in the country only one Orthodox Church, one Old Believer church, one Lutheran church, etc.

At one time, the Moscow Patriarchate applauded this method of guaranteeing church monopolies, which was unthinkable in other countries of the post-Soviet space. (Even in Russia, nearly 10 Orthodox denominations are registered.) But given the global geopolitical shift that began after 24 February, what once seemed like a privilege for the Latvian Orthodox Church now seems like a vulnerability for the Latvian government.

Head of the Latvian Orthodox Church Primate Alexander (Kudryashov). Photo: The Riga Nativity of Christ Orthodox Cathedral

The Orthodox Church of Ukraine has already achieved recognition as autocephalous. (In eastern Orthodoxy, an autocephalous church is one whose highest bishop does not report to another higher bishop.) It did so mostly on its own, albeit with some government support; by comparison, then, the position of the Latvian Orthodox Church, which forms part of the Moscow Patriarchate, seems passive and possibly complicit.

The head of the LOC, 82-year-old Primate Alexander (Kudryashov), is a bishop of the “old formation,” ordained when Latvia was part of the Soviet Union. In the age of Latvian independence, his efforts have mainly been aimed at preventing the revival of other “alternative” Orthodox groups in the country. Some such groups have declared their intention to revert to the religious status quo from before World War II, when the LOC, headed by St. John (Pommers), was part of the Patriarchate of Constantinople. For example, the Autonomous Latvian Orthodox Church, which emerged in the mid-nineties and was headed by a “fugitive” cleric of the Russian Orthodox Church, Archbishop Viktor (Kontuzorov), announced its return to the Patriarchate of Constantinople. But for many years, the Latvian government has refused to register this alternative group.

In spite of its purported loyalty to Moscow, the Latvian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate (LOC-MP) has always managed to get along with the Latvian government. In 2019, Latvia’s parliament passed amendments to the “confessional” laws, introducing a “settlement requirement” for bishops — meaning it required them to live in Latvia. Primate Alexander himself was happy with this change; the new law put an end to the scheme, which had been brewing among leaders of the Moscow Patriarche, to replace him with some young protege from Moscow.

This protege did not conform to the new settlement requirement, and so the Latvian government has still not agreed to a visit from Patriarch Kirill, the head of the Russian Orthodox Church, to Latvia.

On the one hand, it could be argued that the current bill constitutes government meddling with internal church affairs. On the other hand, however, the situation in the contemporary Orthodox world is so atypical and unprecedented that the Moscow Patriarchate — which has publicly supported the enormous and obvious violations of the ten commandments on the territory of Ukraine — now appears too toxic even for its most formerly loyal factions. Thus the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate (UOC-MP) completely severed its ties with Moscow at a cathedral in Kyiv’s Feofaniya Monastery on 27 May. As justification for this unprecedented split, the UOC cited the Moscow Patriarchate’s disregard for the ten commandments and its rejection of the very foundations of Christianity.

The new Latvian bill — which would split the LOC from the Moscow Patriarchate in the same fashion — is supported by the church’s leadership and the majority of its clergy. Because the path to gaining ecclesiastical independence is very complicated and lengthy, and the elderly Primate himself is unlikely to find the strength to start this process, the adoption of this law by the Latvian government removes the responsibility from the church administration.

This approach is not unprecedented. For example, in Ukraine a “soft law” had been in effect since 2018 which required religious organisations whose ecclesiastical centres were in territories labelled as “aggressors” by Ukrainian Parliament to indicate the name of these foreign states in their official titles. This law was clearly directed at the UOC-MP, which — thanks to the tragic events of this year — itself renounced its connection to the Moscow Patriarchate.

A still more interesting precedent took place in Ukraine 100 years ago, when Symon Petliura’s government adopted a law called “On the Ukrainian Orthodox Autocephalous Church” (UOAC) on 1 January 1919. It was not possible to accomplish the law’s goal — making the church autocephalous — because in that historical period power in Kyiv was changing hands too frequently to accomplish anything at all.

But that day set in motion the history of the Ukrainian autocephalous church. The process launched by the law reached its high point in October 1921 with the creation of the UOAC, whose bishops were ordained “in a revolutionary impulse” by ordinary priests and all the people who gathered at St. Sofia’s Cathedral in Kyiv.

Introducing the new Latvian bill, president Levits emphasised that the problem of ecclesiastical jurisdiction must be solved by the government, since after the 24 February, the existence of the Moscow Patriarchate in the free world became “an existential question for society and national security.” The president added that the law was intended to restore the historical status of the Lithuanian Church — that is, to return it to the authority of the Constantinople Patriarchate.

Because all factions of the Latvian parliament have preliminarily supported the bill, it will undoubtedly come into effect in the very near future.

It is possible that the Moscow Patriarchate or Russia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs will register an official complaint, but in the contemporary world this no longer bears any significance.

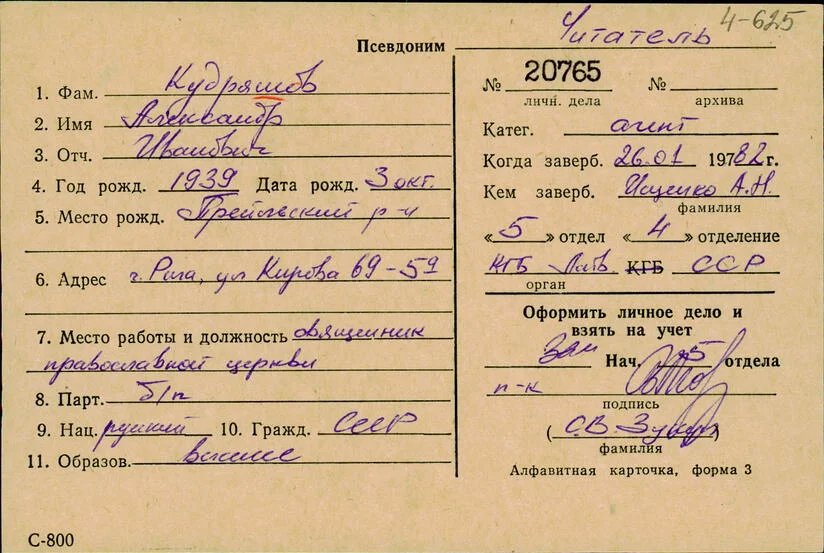

Primate Alexander’s registration card, found in the archives of the Latvian branch of the KGB.

The main problem facing the LOC-MP is the complicated personality of Primate Alexander. In 2018, the primate’s registration card was found in the archives of the Latvian KGB Unit; it says that he was recruited by the unit in 1982 with the agent pseudonym “Reader.” This discovery gave rise to a flurry of indignation in the Latvian press and civil society. According to Latvian laws, exposed agents of the Soviet special services are subject to “lustration” (a form of public dishonour that was often part of “decommunisation” efforts; it can, among other things, bar a person from high-ranking positions in the new post-communist government). However, Primate Alexander does not occupy any governmental or municipal position, so he continued — albeit with a slightly guilty aspect — to hold his esteemed post.

Moreover, the private life of Primate Alexander — who, in a past life, served as a bartender at the Riga restaurant “Tallinn” — has more than once fallen under the scrutiny of the Latvian media.

Primate Alexander’s authority within the clergy and the congregation is already tenuous, so the LOC’s support for the government’s bill has become for the primate a much-needed boost, allowing him, in spite of everything, to continue to govern a patriotic Latvian church that shares European values.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]