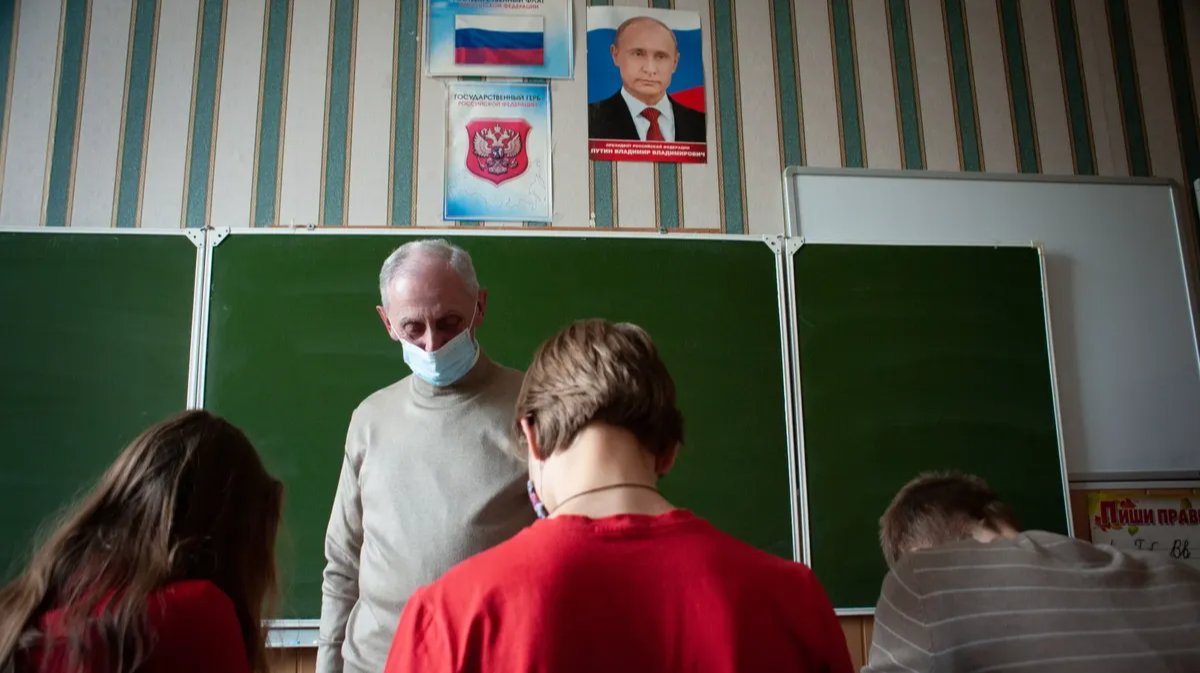

Russian high school and kindergarten teachers have been offered to spend the next school year in Ukraine’s occupied territories — education officials have also been called on to ‘russify’ Ukrainian curricula. Novaya Gazeta. Europe spoke to the teachers, educators, and methodologists who volunteered to go to the occupied regions about the reasons behind their actions.

In late June, The Russian Ministry of Education announced that it would provide «assistance for a wide range of educational needs» in the occupied Ukrainian territories, subject to «urgent need.» The announcement was made in response to media reports about teachers potentially being sent to the so-called «DPR».

As of today, 230 teachers from 33 Russian regions have confirmed their intent to work in occupied Ukraine, and have been listed into a corresponding database. In early July, the database, provided to Novaya Gazeta. Europe by the Alliance of Teachers, mistakenly popped up on the Dagestan government website. The volunteers include teachers, school principals, methodologists, kindergarten teachers, drivers, and regional officials.

In July, Russian Education Minister Sergei Kravtsov handed out certificates to schoolchildren from the Zaporizhzhia and Kherson regions of Ukraine, promising to bring the entire education system in the seized territories to Russian standards by 1 September — the start of the school year.

In the Kherson region, 20 teachers and officials from Krasnodar will help «russify» school programmes. «Our main job is finding out which schools need methodologies and curricula,» explains Vitaly Pavlenko, deputy head of the education department of the regional Ministry of Youth Policy. «We’re also organising field trips for children from several schools to our region [Krasnodar].»

Kindergartens in the occupied territories will also receive «methodological support» — this includes training and seminars for teachers, as well as the adoption of the Russian legal framework and language. «I’m expected to go on long business trips to the LPR, where I’ll provide managerial support to local educators,» says Tatiana Taratinova, head of the Mankovsky kindergarten in the Rostov region. «The point [of our work] is to stop all attempts at ‘bending’ the Ukrainian program and bring the system in line with the Russian format. My task is making this transition less painful».

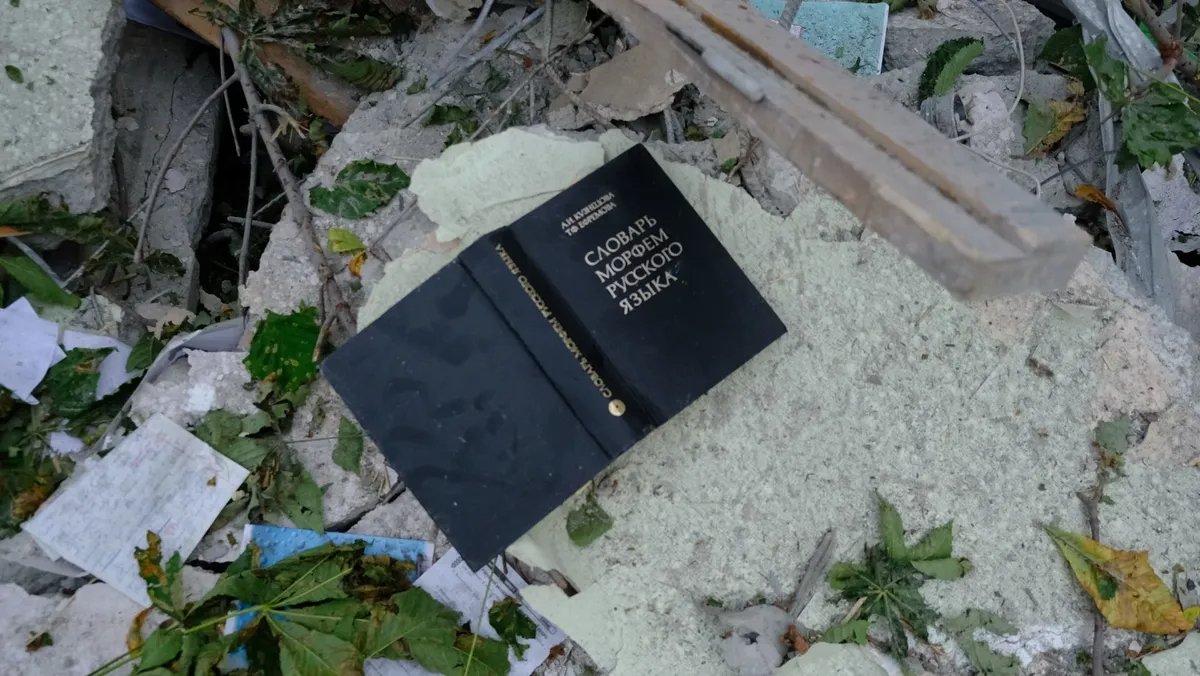

The wreckage of the school after the shelling of Kharkov by Russian troops. Photo by Abdullah Unver / Anadolu Agency / Getty Images

‘‘If I have to teach — I’ll teach history, and if I have to fight — I’ll be a marksman’

Konstantin Matyukhov, deputy principal and history teacher at School No. 97 in Omsk, on his way to the ‘LPR’:

I don’t just want to be among the first who are ready to help their motherland, but I can actually be useful. I work as a deputy head teacher in a school now, and I also teach history. I have three higher education diplomas: one in history and two managerial degrees. If needed, I could even take up arms — I’m seriously considering this option. I was a sniper in the army, and I’m a reserve lieutenant colonel. If I have to teach — I’ll teach history, and if I have to fight — I’ll be a marksman.

In addition, as part of the Cossacks, I’m the deputy of the Omsk regional ataman for the organisation of military-patriotic education and youth training for army service. I’m active in the cadet movement — I’ve been there from the start: my cadets have won first places in competitions in Russia and in Kazakhstan. I also have diplomas and awards from the Omsk regional Ministry of Education.

In the LPR, I’m going not only to teach children, but also to conduct patriotic extracurricular work, as well as to help our people come closer to each other. After all, there can be no division between Russians and Ukrainians, because we are one Russian people.

Under the tsar it was like this: “Velikorossy” (“Great Russians”), “Belorossy” (“White Russians”) and “Malorossy” (“Little Russians”) — we’re all Russians. There is no Ukrainian and Belarusian — these are the two dialects of the Russian language.

There’s a lack of teachers everywhere, including Russia. That’s not the reason for me going. I have four grandchildren, and I just want to make them proud. In terms of fear — I’m not afraid of anything anymore. When my wife left me, I lost my family and it was like I lost myself. Now, I’m not burdened with anything — besides, I want to find my relatives. They moved from Kyrgyzstan to Chukotka, and then left for Ukraine and now they live in Krasny Partizan in the Luhansk region. Although I only know their last name, I still hope I can find them.

‘My wife wants her own garden’

Yuri Baranov, a history teacher from a grammar school in the town of Chusovoy in the Perm region, headed to Zaporizhia:

My wife and I may be given a plot of land in the Zaporizhia region. We’re pensioners — we’re 60 years old — so we’re really hoping that our application will be approved. My wife wants her own garden at home.

Before 2014, I lived in Ukraine and I understand how locals treat Russians — there’s a lot of bitterness and hatred. If I’m sent to the city, I can still hope for tolerance, but if they send me to the countryside, I will have to live in semi-isolation. It’ll be very difficult for us without a Russian-speaking environment.

I have a personal dislike for Ukraine. Not for the people, but for the state, which has been brainwashing its citizens and fostering hatred of Russians for 30 years. Despite Putin’s statements about the trial of fascism, we won’t be able to destroy all Ukrainian Nazis — that’s unrealistic — so we have to solve the problem using other means.

The territory where I hope to move — as a historian, I consider to be Russian. As a Belarusian, I think the same. It was called that — Novorossiya (“New Russia”). I'm 60 years old and it was very frustrating to watch a great country give up its position [in the world]. But, as Nicholas I said — “Where the Russian flag was once raised, it should never be taken down.” Maybe I’m a chauvinist and imperialist, but I grew up in the Soviet Union, and I have the same views as I did when it was still around. I’m sure that older people in Ukraine hold the same opinion.

A school destroyed by shelling in the Bakhmut, Ukraine. Photo by Diego Herrera Carcedo / Anadolu Agency / Getty Images

‘Melitopol has a good environment, it’s close to the sea’

Daria Ganieva, English and Russian teacher from the Pochetna educational and educational complex in Crimea, on her way to Melitopol:

I came to Crimea from Siberia and haven’t yet found a full-time home. Of course, I’m scared to move, but I’m hoping for a place to live along with a decent wage. Besides, Melitopol has a good environment and it’s close to the sea.

You can be scared anywhere. It really depends on the person, whether they’ll be affected by the conflict. I don’t have a hostile attitude towards any nation and I don’t care about politics. You have to stay human under any circumstances.

Wherever I work, I always focus on the results. It’s important for me that the children win competitions and get a good education. That’s impossible without good teachers, and teachers are in short supply everywhere. All the more so in the conflict-ridden territories, because of the fear of the military operation.

Just like in Crimea, Melitopol will have its own referendum, and the people will decide to join Russia. But even if Ukraine regains control of the Zaporizhzhia region, the people won’t be abandoned. As a last resort, we’ll be evacuated or supported somehow.

‘People are crying, hugging, and kissing our soldiers’

Andrei Chetverkov, a music teacher from school No. 4 in Elista, is going to the ‘DPR’ or the ‘LPR’:

I applied out of a feeling of patriotism. We have to help people, our Slavic brothers, our compatriots, even though officially they still live in another country. The kids need to learn, to keep up with life, and there aren’t enough teachers. They shouldn’t be just hiding from the bombs.

I’m not afraid of going. Everywhere’s unstable these days: coronavirus, the environment, emergencies.

If the DPR wants to join Russia, let it follow our example.

After all, “Malorossiya” (“Little Russia”) was part of the Russian Empire — a single power — for centuries. I’m not talking about Western Ukraine, let them decide for themselves — that’s up to the politicians. The Donbas has always been Russian and will never be Ukrainian. Even though the DPR and the LPR broke away during the revolution and perestroika, they remain historically Russian territories. That is, the people there are Russian — they think and speak Russian. For that reason, 99% of the inhabitants [of the DPR and LPR] voted for reunification with Russia.

Only if it comes to a global conflict can Ukraine take these lands. In any other case, under any pretext, under any threat, we will not surrender the Russian people. Every day on TV they show people there crying, hugging, and kissing our soldiers. I understand that the Ukrainian media shows very different things, but I trust my reporters and my TV channels more. I don’t watch anything else.

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]