On 18 July, Tatyana Novikova, Professor at Belgorod State University’s Pedagogical Institute, linguist, Doctor of Science and “the best scholar” in the region, was fined 30,000 rubles (€535) for “discrediting” the Russian Armed Forces. The university moved even faster to force Novikova to publicly explain herself before her colleagues and fired her for “engaging in immoral practices” ahead of the court hearing. Novikova’s students had to defend their theses without an adviser.

“I am a linguist and I do understand the meaning of the word ‘discredit’. Therefore, I know that I in no way could discredit the armed forces,” Tatyana Novikova said with a melancholic smile. The frail and youthful woman sat down for an interview with me in her flat in the outskirts of the city.

Belgorod was struggling in the heat of over 30°C. The Kyiv cake, which I bought because it was highly recommended in the shop and not because of its name, began melting while I was in the taxi. Rescue workers were taking down the building debris left after a direct missile had hit the central part of the city in the early hours of the morning on 3 July. There was still a week to go before the court hearing which would ultimately find Novikova guilty. She could barely believe what was happening.

“The word ‘discredit’ presupposes being inside the system,” she told me, making the case for why the court would ultimately back her.

“I can discredit myself as a linguist, as a teacher. But I cannot discredit the army because I have nothing to do with it.

You, for example, can discredit yourself as a journalist. While only a service member can discredit the armed forces. Does this make sense?”

It did. I also have a very good understanding of the Russian language, unlike those patriots who hastily drafted the law about “discrediting” the Russian army. But while, at that moment, I did not know all the details of Professor Novikova’s case, I could very well imagine the verdict that the court would pronounce. Since it was about the army, the woman would at least receive a fine.

I looked up Tatyana Novikova on social media platforms to schedule an interview. I found her profile on VK (Russian social network — translator’s note) and started reading her posts. I truly enjoyed the music she shared on her page. Impeccable Russian, immaculate politeness to other people and passionate reviews from students. I felt like we were on the same wavelength with this woman even though I did not know her at the time. I messaged Novikova privately to ask for a meeting. The professor responded, saying that she did not want “any fame”. But later, she reluctantly agreed.

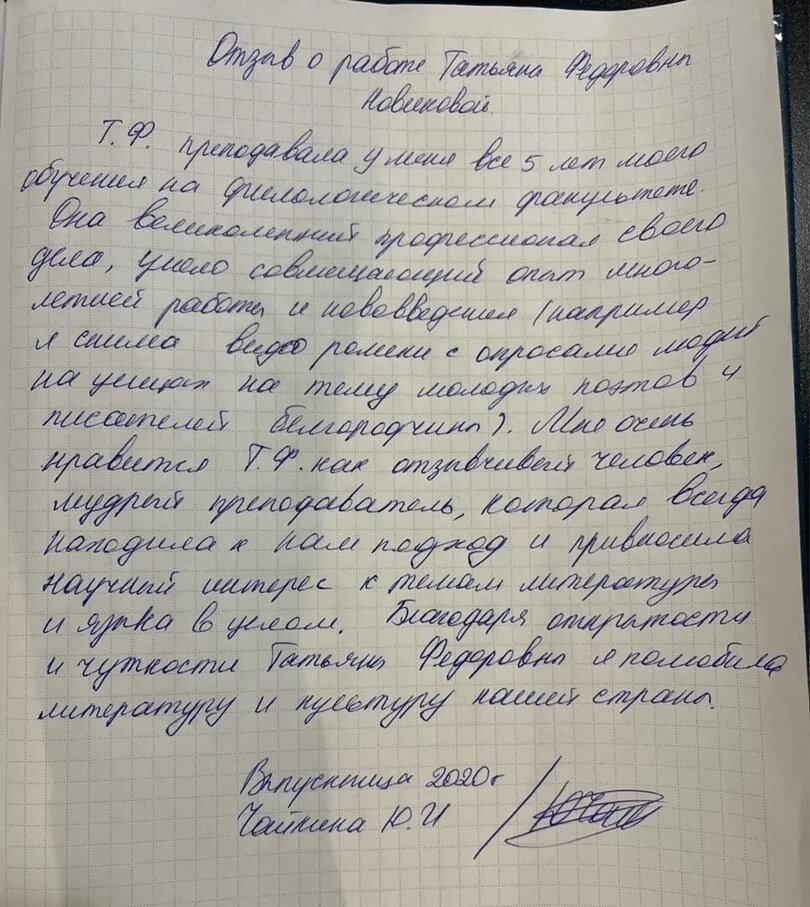

A graduate’s review of Tatyana Novikova’s class

I would later still need to look for other university staffers to clarify the details behind Novikova’s dismissal. The professor herself refused to speak about her colleagues’ actions and wanted all questions to be about her only.

Professor Novikova’s flat is not what a professor’s flat should look like. The one tiny room is full of books, more books, even more books, there is a massive cat and then there is Tatyana herself, the DSc who worked in Belgorod State University for 35 years, almost half of her life.

“Once burglars broke into my flat while I was not here,” she told me with a laugh. “A police officer came to take a statement. I told him that I am a professor. He stopped and looked around the room. Yes, I told him, I should have a private office by law. Here it is: a private office, a living room and a bedroom all at the same time.”

She poured me a cup of cold tea made from dried berries that she had picked herself in the forest next to her friend’s country house.

Now, she barely has any friends left in Belgorod. They started to disappear after 24 February and went completely silent when Novikova was sacked.

Belgorod is the Russian city closest to Ukraine. Ukrainians were always coming here, especially from Kharkiv. The Russian language and literature department (where Novikova worked) is headed by Irina Chumak-Zhun, she graduated from a university in Ukraine’s Poltava and defended her PhD thesis in Kyiv. It is very hard to find a person here without Ukrainian roots or family in Ukraine.

Tatyana Novikova has brothers, sisters and cousins in Kharkiv. She can freely read poems by Ukrainian authors written in Ukrainian. Her favourite poet is Lina Kostenko who famously banned translation of her works into Russian and rejected the title of Hero of Ukraine, saying, “I will not wear political jewellery.”

“When it all started on 24 February, I could not stop crying for two weeks straight,” Novikova said. “A friend of mine came to see me, saw the state I was in and said, ‘I have a different opinion.’ I burst into anger. Because ‘a different opinion’ can be about a book or a movie. But I do not understand ‘a different opinion’ about people dying.”

Tatyana Novikova. Photo from her personal archive

‘She doesn’t work here’

The Pedagogical Institute is structurally a part of Belgorod State University. Novikova joined it back in 1987. She got her PhD and DSc degrees in Moscow. She gave lectures about teaching Russian as a native language all over the country. She is believed to be one of the best specialists in the field in Russia and the only one in Belgorod. She authored many teaching methodologies. She is also involved in studying linguistic variations through the prism of regional traditions and cultures. She spoke at conferences all over the world. But she dedicated almost all of her professional life to Belgorod State University, 10 years in village schools aside. She was given the title of professor two years ago. A year ago, her work contract was extended by five more years after a careful selection process. So, when I needed to interview Novikova, I found her work phone number on the university’s website.

“She doesn’t work here,” a female voice told me.

“Never worked or doesn’t work anymore?” I asked.

“D-doesn’t work,” the voice stumbled.

The website still has a profile on Professor Novikova. It says that Tatyana Novikova enjoys “great standing in the community of Russian language scholars”, she “has proven to be not just a top-class specialist and researcher but also a socially active, responsible and compassionate person.” Novikova is described as “a person of duty, energetic, focused, diligent, who is able to be creative about tasks, think outside the box and fascinate others with her ideas and findings.” She won the title of Best Professor of the university several times. She was recently even awarded a certificate of merit from the Russian Education and Science Ministry.

“Are you sure?” I asked the woman on the phone.

“I am the head of the department,” the voice replied with irritation and hung up.

If it was indeed Irina Chumak-Zhun, then I can understand why she did not want to continue the conversation. It was she who presided over the university review of Novikova’s conduct after her terrible transgressions.

“Back then, Irina used to say that Tatyana should not be so proud of her knowledge of Ukraine,” a university employee who wished to remain anonymous told me. “I don’t know what Irina herself thinks about this but her father and sister live in Poltava.”

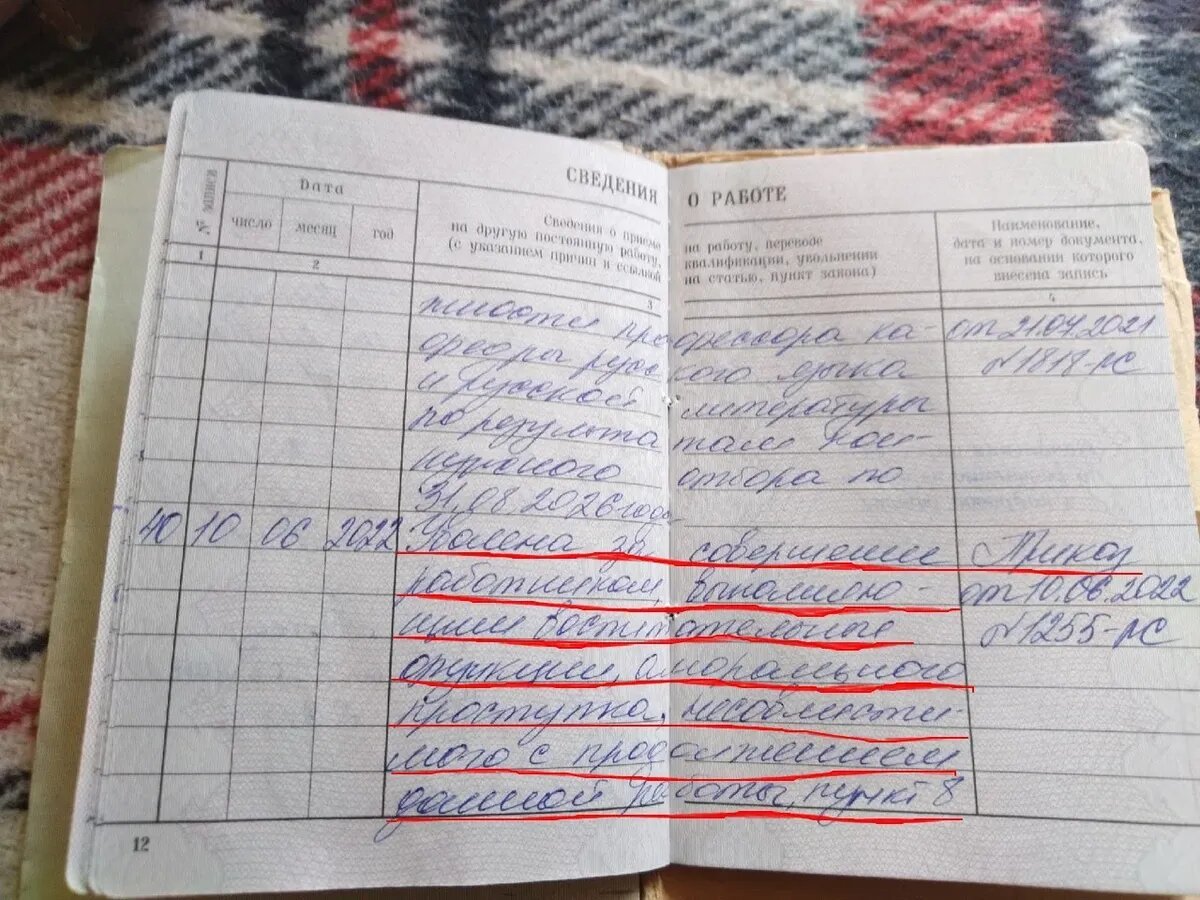

Novikova was fired on 10 June. Very quickly, within a day. The reason given was, “the employee fulfilling education functions committing an immoral act that is incompatible with the line of work.”

Tatyana’s employment record book with the note about the reason for her dismissal

Afterwards, Tatyana Novikova went online to find out what an “immoral act” can be in a work context like hers. Turns out, the “immoral acts” are: theft, bribery, alcoholism or intimate relations with students.

“Maybe it’s for the best,” she shrugged. “I thought to myself that it’s time to calm down and take care of myself. For a long time, I have wanted to write a book about my granny.”

‘Immoral behaviour’

It so happened that Tatyana Novikova has a lot of relatives living on the other side of the barricades, in Kharkiv.

“It was a city of more than a million people and now it’s half empty,” she sighed. “The wife of one of my brothers tells me that, everyday, people go to clear the debris left after shelling, and the mayor goes with them. People work for free, the only thing they get is fresh bread. The other brother used to dream about ‘Putin’s arrival’. Now, I tell him to come visit me, and he replies that he will never cross the Russian border again. His wife is a typical housewife, she used to only be interested in her country house flowers and pickling vegetables for the winter. After learning about my dismissal and other unfortunate turns of events that have happened because I cannot accept any war, she wrote to me, ‘Tanya, don’t cry your heart out. You can’t prove anything to those who have not lived through what we have.’”

Oleg Polukhin, rector of Belgorod State University. Photo: Belgorod State University

Oleg Polukhin, rector of Belgorod State University, spoke to the local media about sacking “the best professor of the university” and said, “Colleagues can express their distrust in a person if they have violated moral and ethical norms. And if the Code of Laws on Labour stipulates liability for violating them, I sign the order to fire that person.” The rector also added that he had received countless complaints about Novikova’s immoral behaviour from “disgruntled citizens outraged that she continues to work at the university”. The rector claimed that the regional governor had also been receiving the same complaints from the same “disgruntled citizens”. According to him, the whole of Belgorod was boiling with indignation because of Novikova’s immoral character.

The Code of Laws on Labour that Polukhin had mentioned was in fact active in the Soviet Union.

The document that was adopted in post-Soviet Russia is named differently. But his slip of the tongue is very emblematic, seeing as Novikova’s firing is very much in line with the practices of those times.

“I am not very active on social media,” Novikova told me. “I only had the VK page to talk to my students. Out of curiosity, I ended up on a page of the town of Shebekino in the Belgorod region, right on the border with Ukraine. I was born there; this page was dedicated to discussing local news. And then I saw vicious comments about a woman that had protested in the centre of the town with an anti-war poster. Turns out she came from Kharkiv. I started defending her. I could not comprehend why she was being targeted that way. Would it have been better if she had written ‘Yes to War’?”

If we try to follow the events using screenshots and web archives, on 12 April, Tatyana Novikova wrote a comment under the slew of other terrible comments aimed at the woman from Kharkiv, it said, “Beware, don’t sing ‘May There Always Be Sunshine! May There Always Be Sky! on 1 May, this means celebrating the Ukrainian flag.”

After that, Novikova herself became a target. “Are you a teacher? You will definitely not teach anyone patriotism,” user Elena Kravchenko wrote in all caps. Novikova carelessly responded, “You can’t teach patriotism, you become a patriot when there’s something to be proud of.”

“I wrote that we are proud of 1945, 1961 and our athletes,” Novikova recalled her past comments. “And then… Then came the very terrible thing that I am accused of.”

“The terrible thing” was her writing that “we are bombing cities, killing people and driving them out of the country” and “turning a prospering country into rubble just because it does not want to live as we do.”

“To be honest, I truly cannot support what is happening now,” she sounded as if she were making excuses. “I know Ukraine very well. I had a close friend, a professor from Kharkiv, who died last year. He was a very educated person, a Russian-speaker, like all people in Kharkiv. We drove around the whole of Ukraine together. I speak Polish, therefore, it wasn’t hard for me to understand Ukrainian, but they all spoke Russian with us, there were no issues. In 2015, we marched together in Kharkiv for the Immortal Regiment. Now, we are told that people were killed for wearing St. George ribbons. But there were many people with the ribbons, everyone who wanted to was marching with them. So, when all this nightmare erupted on 24 February, I just could not understand: where did they find Nazis in Ukraine?”

User Vitaly Kasumov told Novikova in a comment, “get a grip on yourself or somebody else will handle you.” It is exactly what happened in a few days’ time.

Belgorod State University. Photo: Belgorod State University

Colleagues

One university staffer told me that several colleagues approached Novikova one by one to loudly tell her how much they did not share her terrible position. Loudly enough so that everyone around would hear. Novikova herself did not understand what was happening at the time. In the month and half since 24 February, she had gotten used to people feeling like it was their obligation to be very much in your face about supporting the “special operation”.

“People have different positions, and I wasn’t paying attention to everyone’s views,” she explains. “A conference, which I was preparing for a while and was supposed to host, was approaching, there were a lot of things going on.”

She was told that the event would take place without her a week before it was meant to start. Then she was suspended from teaching. Then she was asked to take a sick leave.

“My blood pressure was hitting very high figures, indeed, I once fainted at a doctor appointment,” she told me. “Of course, I did get the sick note. I could already see that it was a misstep to write all those comments. I should not have brought myself down to talking to people who would misinterpret my comments anyway. But I did not see it as any kind of offence. Furthermore, after working in schools and universities for 45 years, I have thousands of students who can vouch that I have never taught them anything wrongful. I was certain that I didn’t even have enemies.”

She returned to work on 8 June. That evening, three university representatives came to see her and handed her an invitation to a general university meeting.

“She was at her wits’ end, I remember, she was taking tranquilisers,” says one of Novikova’s former students who dropped by to support her.

Representatives of each department were delegated for the university meeting.

Each representative was told to leave a signature in a special journal to prove their attendance. The only one who was not allowed to do so was Novikova.

The director of the Pedagogical Institute led the meeting. At least half of those present, probably, were Novikova’s students at some point. Many were sitting with their eyes glued to the floor. One of her former students stood up and mumbled, “Tatyana Novikova is a brilliant teacher, she just made a tiny mistake.” Another quietly added, “Tatyana Novikova has never discussed this with students.”

“I also kept quiet,” says a university staffer who agreed to speak with me. “I am ashamed now but I was very scared then. Before, I have only read what things were like in the 1930s in the Soviet Union and now I felt it myself. My mother told me not to say anything. She said that they would remember my name and then I would be targeted.”

Another colleague loudly demanded that Novikova stand up before them and admit what her position on the special military operation was. As if her repentance would be the end of it. She did stand up, though. And said that she had the right to have an opinion and was not obligated to share it. However, which decision to take was their moral choice because some of them did love to give their students the “moral choice” topic for essays.

The representatives concluded that Novikova did not regret her delusions and issued her a reprimand. Members were rising from their chairs one after another to declare that they disagreed with Novikova in every way possible.

“I truly did not know what I was to do,” Tatyana told me, half-smiling, in her kitchen. “Disown my brothers and sisters in Ukraine? All the books I’ve read? Everything I’ve seen Ukraine and know about it?”

And then it became clear that the decision had already been made regardless of her actions or words, which would not have changed anything.

“The meeting was taking place after my dismissal had already been signed,” Novikova smiled ironically. “I was only formally reprimanded, but the decision had already been made. And I was also forced to write an explanatory note to the rector! I remember that the faculty dean took that paper from me without even looking.”

On 10 June, Novikova only had to pick up her documents from the HR department.

‘Special operation’ and peace

“At first, I thought that all these reports about my ‘case’ and these accusations had tarnished my reputation,” Novikova said with a sad smile while hugging her massive cat. “I barely had any friends left in Belgorod. But then, suddenly, strangers from different cities started messaging me. It turns out that many do support me. A student from a different faculty wrote, ‘I am proud of you and wish you could be my teacher.’ Students and colleagues from Moscow, St. Petersburg and other cities write to me. A few days ago, some people sent me money. I called one of them to try and explain that I am not really in need. He said, ‘this is to pay the fines. This is our contribution to the fight for peace’.”

Those who have been at Belgorod State University long enough say that they only remember one other case of dismissal before Novikova’s. It was in the law department, a very questionable corruption case. A general meeting was also convened then. The only person to speak in defence of the accused was Tatyana Novikova. She just stood up and said that a person should not be accused without evidence.

Towards the end, I asked Tatyana Novikova about the future, possible conversations with colleagues and former friends. Because at some point, I added, it would all be over, there would be peace and victory, whatever anyone’s idea of it is now…

“As a linguist, I can tell you that you cannot win a ‘special operation’,” she told me. “You can win a war, and we have a special operation. You can only end it.”

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]