On 17 July 2014, a Malaysian Boeing MH17 was shot down from the skies above Ukraine. Then, 298 people were killed, 80 of them minors. That was the first time Europeans faced the war in Ukraine so painfully and intimately, the war that, at the time, was considered by most people to be a local conflict, somewhere on the periphery. It was then that the residents of the Old World (first as part of the group of victims’ relatives, later on, came others, who followed what happened after the tragedy — followed the investigations and court proceedings) saw clearly for the first time how the Russian propaganda machine works: it filled both Russian and European spaces with constant disinformation about the crash. The prolonged investigation became a fight not for justice but for the truth.

It has been eight years. Now, all of Europe has had to face these things — the war and the lies coming from the Russian government.

What do relatives of the killed passengers think about the current events? What have they been doing since the start of the war? Do they continue, as they did before, to hold only the leaders of Russia accountable and not the whole population? What are they expecting from the verdict that is to be pronounced by the end of the year?

Looking for answers, Ekaterina Glikman went to four Netherlands provinces and visited five families, all of which had lost close ones in the MH17 crash.

The first story

Hans de Borst

Monster, province of South Holland

The victim: Elsemiek

The town of Monster is located near the sea, just 6 miles away from the Hague — the place serving as the symbol of hope for justice for so many people across the world. My bus arrives in Monster a little bit ahead of schedule, so I walk down the deserted picturesque streets and find that the church cemetery’s gates are open. There, behind the gates, my attention is at once caught by a small bronze sculpture: a hand holding a newborn. It’s time, I think.

Sculpture at the Monster cemetery. Photo: Ekaterina Glikman

The first Dutchman, whose door I have to knock on, lost his only daughter in the crash — she was 17. His name is Hans de Borst, he is 59. I do not have the time to knock — he is waiting for me by the door: “It’s good that people from your country are still interested in the MH17 case, seeing as now, due to war, you have other things that you have to be thinking about. But these events are connected: our children were killed by Putin too, the same as Ukrainians now,” Hans starts off.

At once, I notice portraits of a beautiful girl on the wall. “Sometimes, we feel as if this were our Dutch 9/11,” Hans says. “But you can’t compare it to what’s currently happening in Ukraine, of course.”

There were four of them on the plane: his daughter Elsemiek, her mother, stepfather, and younger half-brother. “Her mother and I had been divorced for 10 years by that point, and my daughter lived in two houses: with them in the Hague, and with me here. The plan was as follows: she would spend the first part of the holidays with her mum in Bali, and then the second part — with me in Spain,” says Hans. Elsemiek had one year of school to go.

Hans de Borst near the portrait of his deceased daughter, holding “Russian Elsemiek” in his hands. Photo: Ekaterina Glikman

“That 17 July fell on a Thursday,” Hans remembers. “There wasn’t any useful information on TV, but I knew for certain that she was on that plane — she texted me before they boarded. And the ground fell beneath my feet.”

The next day, on Friday, he went to her school. All her classmates were there.

They were crying, and Hans could barely handle it, but he did not think that he had a choice: he felt that he had to be there, with the children. And a year later, when they got their diplomas, he was also there with them.

On 19 July, a Saturday, police came down to his house. They had to collect information that would help to identify Elsemiek. They asked about her teeth, tattoos, and a piercing. “She had a ring that she had got from her grandma. This is how they identified her later on,” shares Hans.

Hans placed the ring in a small glass box, and now it is always with him — on his watch strap. “This is the most important thing that I have left of her,” he says.

Hans displays Elsemiek’s ring. Photo: Ekaterina Glikman

Her passport has been returned to him, too. With a boarding pass inside! Hans shows me the passport, and suddenly throws it on the floor as hard as he can, demonstrating how it fell from the sky to the ground. It is a bit eerie. “It’s good that her body remained in one piece. Others were receiving a new body part every month,” is his terrifying continuation.

Hans has spent his entire life working in a bank, but a few years ago he left his job. Yes, the decision is connected to the crash: first of all, he could not concentrate on his work any longer, secondly, the court proceedings started, and it was important for him to be there. He sometimes still does work projects from home, but he spends the majority of his time on making sure the MH17 flight is remembered. He has a girlfriend, she lives in the countryside, and they see each other several times a week. “And that’s good,” Hans adds.

He was always interested in politics, more so after the crash, especially when it comes to Russia. Hans thinks that in his next life he is going to be a journalist. “Currently, no one can stop Putin, but someday he will not be there anymore,” he predicts. “And Russian people will see that the world isn’t against them.”

Elsemiek’s passport and boarding pass. Photo: Ekaterina Glikman

The municipality of Westland, which Monster is a part of, can be easily seen from space — all its territory is covered with greenhouses that glisten in the sun. Westland is the main exporter of vegetables and flowers in Europe. From here they were, of course, also exported to Russia. After the MH17 crash, the government prohibited export to Russia, but just a year later, a local mayor began talking about restarting deliveries. “I was against it,” says Hans. “A lot of people put the economy before justice. I don’t agree. Justice should be served first. But we continued exporting our flowers and buying gas. Europe was being naive. I asked the prime minister: how come? He replied: well, we have to continue negotiating with them, so we can have opportunities to remind them about the MH17 crash. But now you can see: Putin isn’t interested in these things — he only cares about money.”

Unfortunately, Putin still has a lot of friends, reflects Hans. And not just Serbia and Hungary. “There are some even in Holland!” he exclaims. “Yesterday, I was listening to Thierry Baudet’s speech (a Dutch Parliament party leader — — E.G.), he was saying: Putin is the best statesman of the last 50 years. Unfortunately, populists have recently become very popular in the West. It’s a problem.”

The most important thing to Hans when it comes to the trial is that all the evidence and proof is presented. “It gave me a clear picture of what exactly happened on the plane,” clarifies Hans. “I know that no one will ever go to prison. We knew that from the beginning.

If Russia doesn’t want to play by international rules, there’s nothing anyone can do about it. But it doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t act. No!

All the investigators, judges — they did their job. It was the right thing to do. Here in the Netherlands, we have our famous objective court. Its verdict will be presented to the entire world. You can’t commit a mass murder and just walk away, thinking that no one will investigate it. This is what justice is.”

Last autumn, he participated in the court hearing that saw relatives of the victims take stand. He held the portrait of Elsemiek in front of the judges, and he felt as if his daughter were there with him. It was harder than he imagined.

It took Hans a long time to realise Elsemiek was not coming home. “She was at the stage of turning into a woman from a girl. She wanted to study. She worked as a waitress, part-time. She brought her friends here, and they watched TV. It takes 20 minutes by bicycle from the place where she lived to mine. When she came down, I heard the bell of a bicycle, then a “click” of the door. These small moments — you miss them most of all,” Elsemiek’s father reflects.

Every year, on 25 April — her birthday — Hans and six friends of Elsemiek go to a restaurant together. The girls tell him about their lives. And he sees a bit of Elsemiek in them. He is curious which of them will get married first. “Sometimes, I think: they do this for me,” he confesses. “But then I see: they do it for themselves too. They’ve been traumatised too. They were 17-18, and they are still thinking about it.”

You can feel how close the sea is by the movement of the flowers in Hans’ small garden, visible from the window. Ever since 17 July 2014, Hans “feels handicapped” but he goes on living. He does things to occupy his time: for example, he jogs on the beach. And during winters, he goes to Austria for a month — to the place where he used to vacation with his daughter — and gives ski lessons to the beginners.

Monster. Photo: Ekaterina Glikman

For a moment, Hans starts speaking Dutch. It sounds like he is thinking out loud. He uses the same short phrases in Dutch as he does in English. He looks at his daughter’s portrait and talks. I stay quiet. It seems as if he is talking to her, and that inspires a feeling of both beauty and pain in me. The talking lasts for a short time, I am not sure if he himself noticed. Then, he raises his eyes and, as if nothing happened, continues in English.

Shortly after the MH17 crash, Hans published an open letter addressed to Putin on his Facebook page. Thousands of people from around the world reacted, including some from Russia. One of them was Kirill from Volgograd. He wrote to Hans: “I am sorry for what my country did to you.” Hans replied: “No, your country didn’t do anything wrong, but some people — they did.” Since then, they have been friendly and talk often. Once, Kirill sent Hans a painting. Hans brings it in and shows me a watercolour portrait of a pretty girl: “Of course, this isn’t my daughter, this is sort of a “Russian Elsemiek”, but it was from the heart and it’s very precious to me.”

After the start of the war, he lost contact with Kirill. But later, he once again reappeared — now, through VPN. Hans always asks him how things are in Russia. Kirill writes that, now, even small children are being taught in school that Ukrainians are beasts. “They say that there are Nazis in Kyiv, but in reality they are the Nazis,” Hans’ friend writes to him from Russia.

“The important thing is: this isn’t West against East”, Hans insists. “These are moral standards against immoral ones. A lot of people in Russia also want justice. There are moral standards in Russia too, there is culture, and it has nothing to do with political dictators.”

The second story

Piet Ploeg

Maarssen, province of Utrecht

The victims: Alex, Robert, and Edith

There is a trail that weaves in the shadow of tall trees on the way from the bus stop to Piet Ploeg’s house. On the right there is a field lit by the sun, on the left — clear dark water of a small channel, adjoined by back gardens of typical Dutch houses, with its colourful flower beds, sun loungers, grills, and bright umbrellas that protect you from the sun. It is quiet, only the birds are singing. A red dog of good breed with long, glistening hair runs towards me, after it, a little behind, walks an old man with a smile on, he is wearing stylish yellow trousers. This paradise on earth is where the chairman of the MH17 Disaster Foundation (Stichting Vliegramp MH17) lives.

Piet Ploeg. In front of him on the table is a box of soil from the crash site. Photo: Ekaterina Glikman

When I arrived, Piet took a pause from an unfinished speech he was preparing for the 17 July ceremony of commemoration of the MH17 crash victims. After Piet’s speech, relatives read out 298 names, one after another.

Piet’s house is full of light, one part of it with its glass walls and ceiling resembles a greenhouse. It is hard to comprehend that a relative of three crash victims lives in this house. Piet himself is also a very warm and inviting person, just like the house. On the sofa and chairs, there are three cats. His kids adopted them, promising that they would take care of them, but, of course, when they grew up, they left their parents’ house without the cats. His daughter became a prosecutor, his younger son an accountant, meanwhile the older son moved to the US, which, to this day, Piet cannot understand. He thinks that life in Holland is much better.

A few weeks ago, a 63-year-old chairman of the Foundation himself went to the US for the first time. So, he went to Washington and he confirmed that he was right all along. Obviously, he was there on MH17 business: the National Air Disaster Foundation organised a meeting for relatives of the passengers of three flights: MH17, PLF101 (the Smolensk air disaster, which happened on 10 April 2010 and in which 96 people were killed, the Polish president and other representatives of the government among them), and KE007 (the Korean Boeing crash, which was shot down by a Soviet jet in the Sakhalin sky on 1 September 1983, 269 people were killed). “It was interesting to hear about the experiences other next of kin had with the Soviet and Russian governments,” Piet says. “Poland didn’t receive the plane wreckage. There was no cooperation from the Russian authorities, the opposite — complete obstruction. There are a lot of rumours that a bomb had blown up on the plane — the relatives think so. The same happened to the Korean plane. It was a different time, but the government's reaction was the same: zero cooperation, only obstruction, and they didn’t even return the victims’ bodies.”

Piet’s brother, Alex’s body was also never found. He is one of the two MH17 passengers, whose remains were never identified. When Piet talks about it, his previously smiling face darkens. On that plane, together with Alex, were his wife Edith and their son Robert — some parts of their bodies were found, yet nothing was discovered of Alex’s — neither body parts, nor luggage. “It’s as if he never existed,” Piet says very quietly. “During the funeral, we had two coffins and three photos. It’s a very strange experience. How do you say goodbye to someone that isn’t there?”

Alex was a biologist, he travelled a lot due to his work in international organisations. He wanted to show his son and wife the place that he himself often visited. “He was a good man, I miss him,” says Piet. He was survived by two daughters, at the time they were 18 and 21. Piet and Alex’s parents were still alive — in 2014, they were 82. Piet was the one who had to tell them. “Mum developed chronic depression,” says Piet. “All she could do was lie in bed. Dad suffered in silence, kept everything inside.”

Alex, Edith, and Robert. Photo from the family archive

Being the chairman of the MH17 Disaster Foundation is a full-time job, even though Piet does not get paid. What does he live on? “My wife has a good job,” he laughs. Before July 2014, Piet was a vice mayor of his municipality, before that, he worked as a financial employee in the Prosecutor’s office and court of Utrecht. It makes sense that, with his experience, he was called on to head the Foundation. So, he decided to dedicate himself to the victims' relatives. “It was important to unite, so we could be stronger together”.

“Doesn’t this job make you sad?” I ask him. “Noooo!” is his reply. “It’s been eight years, the sadness is now in the background. The case that is in the court right now is very interesting. There are 70,000 pages. I’m reading them right now. There are also parallel courts happening. And it’s important that someone is constantly involved in these processes, so they can inform the next of kin.”

He was at all 67 hearings of the MH17 case, which is being tried in the Netherlands, at all the European Court of Human Rights hearings in Strasbourg, and at all the hearings of the International Civil Aviation Organisation. And there are years more to come of such work.

While talking to “other” victims’ next of kin in Washington, Piet saw that they not only have something in common — the way their communication with Russia developed — but also have a striking difference — their relationship to their own countries. “We, unlike them, received colossal support from our government,” Piet explains. “It’s unique. At least two times a year, we meet with the prime minister, the ministers of justice and foreign affairs.

If we need something, I have the prime minister’s number. I can call him and ask for help, and he will provide that help.

The government gave us the funding for the Foundation, too. They helped us hire lawyers for court proceedings. We share the same pain as they do, yes, but not the same frustration.”

Not far away from Maarssen where Piet lives, there is a small municipality of Hilversum, 15 residents of which died in the crash. Every summer, sunflowers are planted along all of the municipality — along the roads and the shopping centres. There is a monument, too — bronze sunflowers. “Last year, the mayor of Hilversum retired, he now lives in our village,” says Piet. “Every year before that, he would go down the houses of every victim, it was something special.”

Every day of the last eight years, Piet has been following all the information on the crash published on the Internet. He knows better than most how the Russian propaganda machine works. He has faced it. Piet tells me that, in the first three days, Russian troll factories posted more than a hundred thousands tweets with various, disorienting versions of what happened, all contradicting each other. And ever since then, the disinformation war never quieted down.

He was never surprised by the Russian government’s behaviour. While laughing, he tells me that it is very consistent. “In the Netherlands, this is impossible. We have freedom of speech. Our government wouldn’t be able to lie like this. But Russia is famous for it. They lie about all the wars, all the crashes. It’s so stupid! If Putin said: we made a mistake, we are very sorry, — there wouldn’t be a need for so many legal procedures. What’s wrong with admitting a mistake had been made? Just admit it!” Piet loudly slams the desk. Overall, he is very warm and smiley, and there are only a few times when he talks quietly and seriously — about his brother’s funeral and now: “For us, for relatives, it would be much easier if they just said sorry. But no. Just lies. Only obstruction of justice. Only alternative theories and tons of false information. Just imagine Peter, who lost three daughters, imagine what he feels like listening to this!”

“Yes, the trial has been going on for a long time,” Piet agrees. “But all our relatives are patient. I respect them so much. They all have reasons to be angry but they always conduct themselves in a dignified and civilised way.”

Last September, 105 people used the right to make a speech at the hearings, Piet was one of them. Speaking at the hearing turned out to be harder than he anticipated — so was listening. He was amazed by the victims’ next of kin, and also by the members of the courts: they are not allowed to show emotions, or cry, and they had to withstand so much grief.

The verdict should come by the end of this year. The court will have to answer three questions:

If it was a Buk missile, then where did it come from? Where from did the shot take place? Are all four suspects guilty — Ghirkin, Dubinsky, Pulatov, and Kharchenko?

Everyone understands: even if they are found guilty, they will not be serving time. Piet assures me that the relatives are prepared for that. The most important thing, according to Piet, is that the verdict will be known across the world, that the public will be aware of it, and that politicians from all over the world will have to react to it, because such a verdict will be impossible to ignore.

“I have my own opinion on Russia — about the government, not about the people,” clarifies Piet. “The Russian people didn’t do this. Russians didn’t shoot down the plane. I think I can speak in the name of all next of kin: this case, for us, is about the Russian government, not about the Russian people. When I found out at the beginning of the war that a lot of Russian soldiers didn’t know where they were being sent, that they thought they were going to exercises, and instead went to war, I thought to myself: who’s responsible? It’s not the soldiers, not the people, but the government. Putin is responsible. When it comes to Russians — I remember the big headline in Novaya Gazeta: Vergeef ons, Nederland (Forgive us, Netherlands). That was the voice of a normal Russian.”

The issue of Novaya Gazeta titled Vergeef ons, Nederland (Forgive us, Netherlands), July 2014. Photo: EPA

January of this year, a month before the start of the war, Piet was a part of, according to him, a historic meeting. It was held in Strasbourg. The hearings on the case of “Netherlands versus Russia” were being held there. “We sat in the middle row,” Piet tells me. “On the right, there was the Russian delegation, on the left — the Ukrainian one. And there was colossal pressure between them. The Russian delegation kept lying. The Ukrainian one was, of course, very angry. And a month later, Putin invaded Ukraine. The signs of the future invasion could be felt at that meeting.”

Piet would very much like to go to the place of the crash, but it was always very unsafe. And now, Piet no longer believes it will ever be possible. He shows me a small crimson plastic box. “That’s all I have from there,” he clarifies. A Dutch director that was filming a movie there brought Piet this box that holds the soil and a piece of molten metal. “At first, it smelled like fire and corrosion, but it doesn’t anymore,” reflects Piet.

The third story

Loes van Heijningen-Gorter and Robbert van Heijningen

Bolsward, province of Friesland

The victims: Erik, Zeger, and Tina

The quaint historic town of Bolsward makes you fall in love with it at first sight. You can enter the town on a small boat, navigate its numerous canals, see the City Hall, considered the second most beautiful building in the country, and visit the ruins of Broerekerk, a Gothic-style church with a glass ceiling. You can also look for the bronze statue of a man leaning against the railings of a tiny bridge over a narrow canal with a bronze fishing rod, and a curious kid pulling at his pant leg.

Bolsward. Photo: Ekaterina Glikman

The town has a population of only 10,000. Local residents think that nothing special is produced in Bolsward at this point, and the only thing the town has to offer is its tourist attractions. However, this is not quite true: Bushido, a brand of coffee that used to be quite popular in Russia, is made here. It is no longer exported to Russia due to sanctions.

This is where Loes and Robbert van Heijningen live. Robbert’s brother Erik, his wife Tina, and their 17-year-old son Zeger were on board the MH17 flight.

In July 2014, Robert was on vacation in France with his family. When he found out about the crash, he could not believe what he heard. He was screaming. He was furious. “Then I realised that the fury, it was like madness,” he admits now. “I was angry at the politicians who offered to go to war (and there were some who did!) to avenge those who were killed. This is absurd. No one has ever been better off because of war. There is a documentary that made an impression on me: it was shot in Israel, there was an interview with a Palestinian guy who lost two of his sons in the war with Israel. And he said: I hate the state of Israel, but I do not have a bad attitude towards the Israelis, my best friends are Israelis. I only hate those several people who are in power and who are making the decisions. And I thought: yeah, that’s it. That’s true. He inspired me to reject hatred.” It is hard to imagine, looking at Robbert’s kind face, that he has ever felt hatred.

Robbert is 65 years old, he is a corporate lawyer. His wife Loes used to work with mentally ill people, before the MH17 crash, but she had to quit. Her boss told her: “You’re grieving too much.” “This is how I lost both my family members and my job,” Loes says. It was difficult to get another job at 50, but Loes did not let that stop her. She started to learn how to overcome loss and grief from a professional standpoint. Then she found a civil service job as a grief counsellor. Loes is now 56 years old, she has a new career, and she is glad that she has chosen this path.

“Many of those who come to us tell me: if you lived through the MH17 tragedy, you know what grief is. And they trust me,” she says.

Loes and Robbert van Heijningen. Photo: Ekaterina Glikman

In the first weeks after the tragedy, they wanted to visit the crash site. They even found a way to do that. But they ended up not going, because their 11-year-old son Jasper was scared that something would happen to them there and begged his parents not to go.

“Why did you want to come there?” I ask them. “To find out what happened,” Robbert says. “To live through our loss. To talk to the locals, to ask them what they feel and think. They suffered, too: they found human remains on the street, there were bodies falling on their homes. Children were finding bodies. It’s terrible.”

Later, Robbert and Loes sent a letter to the residents of Hrabove, a village that was at the epicentre of the crash. “And we got a reply!” Robbert exclaims. “They grieved with us and thanked us for thinking about their pain too. We were very touched.”

Their son Jasper found it the hardest to deal with the tragedy. Soon after the plane crash, he went back to school. At first, everything was fine, but in three months, his grades went down and he could not concentrate on his studies at all. He often had fits of anger, and it was hard to communicate with him. The boy was scared of everything. Only after talking to other relatives of the MH17 crash victims, Robbert realised that this was a consequence of the tragedy.

They were lucky to find a good child psychologist. The therapist explained to them that the MH17 disaster is not just their personal loss, the entire nation grieves with them. It is harder to overcome a loss of this scale.

Jasper brought a photo of Erik, Zeger and Tina to his first therapy session. At bedtime, he asked Loes: “Mum, I had to tell the therapist that they’re dead, but they are still on vacation, right?” Loes did not know how to respond to that. She frantically looked for the right words to say. She finally said: “What do you want me to say: that they’re on vacation or that they’re dead?” Jasper thought about it for a while. Then he replied: “Maybe you should tell me they’re dead, or you’ll be lying, and you never lie to me.”

Jasper was scared for a long time. He used to say: “If I get on a plane, I will die. If I get on a train, I will die. If I get on a bus, I will die.” The therapist offered them to take a trip on a train together, and so they did. “He was so frightened. He was cowering, he became so tiny,” Loes recalls.

“I told him: “Jasper, mum and dad are with you.” He replied: “Zeger was with his mum and dad too, but they are all dead.”

It took him three years to overcome those fears. Jasper is 19 now. He is a tall and handsome young man with a firm handshake. He studies law at university.

Robbert’s brother Erik worked at a bank. His wife Tina taught Dutch. “It seems that Erik was thrown out of the plane,” Robbert says. “Most of his body was found immediately, only his legs were missing. Tina and Zeiger crashed and exploded inside the plane, so there were multiple fragments of their bodies.”

Tina, Zeiger, and Erik. Photo from the family archive

Every time they found another fragment, the police knocked on the van Heijningen’s door to inform them of that. At some point, Robbert and Loes said: “Enough”. They signed a document asking the police not to notify them if any new fragments were found.

Erik’s family lived in the aforementioned Hilversum, which lost 15 of its residents in the crash: the highest of any town in the Netherlands. Hilversum installed a beautiful monument of fifteen bronze sunflowers to honour the victims of the crash: smaller flowers that are not blooming represent the children, and larger sunflowers represent the adults killed in the tragedy.

Robbert follows the court proceedings online. He was also among the next of kin of the victims who took a stand in court. There, he talked about his brother, sister-in-law, and nephew that were killed, about the trauma of Jasper and Loes, and about the residents of the Ukrainian village of Hrabove. It is not that important to Robbert whether the four defendants are found guilty. The court hearing itself is what matters to him. Truth is what matters to him.

One time, the van Heijningen family had a visit from a Russian journalist. He acknowledged that he works for the state and only writes what they want him to write. After the interview, they spent some time talking. The journalist said that he lives in St. Petersburg, that he has one son, like Loes and Robbert. “A nice man,” Robbert says with a smile.

There was another less pleasant encounter: two weeks after the tragedy, he was invited to a meeting with three Russian reporters. “Our friend, a priest, told me: Robbert, be careful, I think they might be from the KGB,” he laughs. “They invited me to visit a place where my relatives would be buried. My friend wrote down their number plates. They really were very strange. It was the only time I ever felt uncomfortable giving an interview. I have never seen their article.”

Robbert is the eldest brother. Erik was a middle child. There is also a younger brother, Ronald. When Russia invaded Ukraine this February, he was with his Ukrainian girlfriend Elena in Kyiv.

They managed to leave the country with other Ukrainian refugees, but it was a very long road home: they travelled by train, by car, and on foot.

Robbert was likely under a great deal of stress. Now, Elena’s father is on the territory occupied by the Russian army, so they know first-hand what is happening there. For eight years in a row, the same war that seemed so far away, has affected van Heijningen’s family directly.

“I don’t blame Russians,” Robbert says. “This is not the fault of common people. I would be crazy if I thought this. A small group of people is to blame: those who are making the decisions. The majority of people want to live in harmony, no matter who they are: the Dutch, the Russians, the Egyptians.” Loes agrees with her husband: “Sting has a song I hope the Russians love their children too. It was written during the Cold War. I often hear it on the radio now. The Russians live in a country that we cannot even imagine. Here, in the West, we live freely. When MH17 crashed in Ukraine, the Dutch were very angry with the Ukrainians who took things out of the suitcases. They called them idiots, they said it was horrible. I disagreed with them: how can you talk about the people there if you don’t know how they live? They are living through a war. There is shelling everywhere, there is no money for food, for clothes. And then a suitcase falls on you, on your home from the sky. Why are we so angry that they took a towel out of this suitcase? If a suitcase fell in your garden here in Holland, no one would take anything from it: we all have towels, money, we can buy everything. The people’s lives are different there. You cannot judge people who live in a different reality. And you cannot judge the Russians, because they live in Russia, not in the Netherlands.”

The fourth story

Anton Kotte

Eindhoven, province of North Brabant

The victims: Oscar, Remco, and Miranda

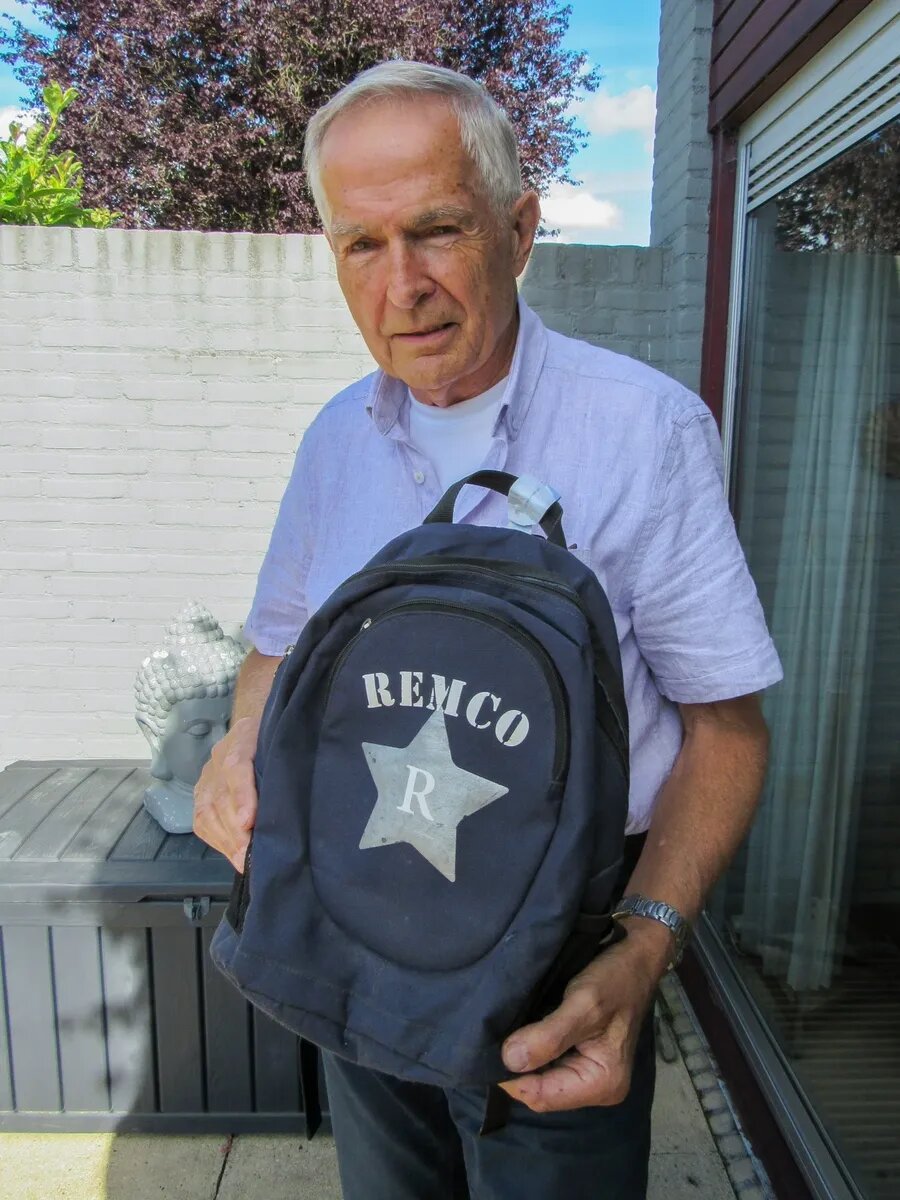

Anton Kotte is a slender and energetic older man. He moves and talks fast. He has an amazing memory for numbers and dates. It is hard to believe he is 78 years old. As soon as I cross his doorstep, he gets right to business and places a photograph in front of me: “My son Oscar, his wife Miranda, and my youngest grandson Remco.”

Anton Kotte holds the backpack of his dead grandson. Photo: Ekaterina Glikman

He remembers every detail from 17 July 2014. “It was a beautiful day,” he says. “We were here in the garden, my wife Hilda was making a barbecue, we ate. And then I saw a picture of the plane on my iPad. And I had a feeling right away. Right away! I ran to the house. I turned on the TV. They were talking about the disaster. It’s hard to describe what it was like. It was hard to believe at first. We spent the entire night in front of the TV. All our family came here, our house was full of people. We tried to support each other. But there was a little bit of hope. I called the hotline on Thursday and Friday, but they only confirmed that my children were on board on Friday night. Since that moment, we knew we had lost them. So, this picture on my iPad was a turning point in my life.

The grief that engulfed us… I can’t even describe it to you. As my wife said, it’s not normal when parents outlive their children.”

A week later, all the next of kin of the victims, a little over 2,000 people, were invited to a large congress centre. The entire Cabinet of the Netherlands was there. The King and Queen were there. At first, the relatives were told all the information that was available at the time. Then, they were given the opportunity to ask questions. And then all hell broke loose, Anton says. All their hopelessness, rage, and frustration came boiling over. “There was a lot of noise. They were moving chairs and leaving the hall. The first question was about money: how do they pay for the funerals of their loved ones. I was so surprised: the first question is about the money! This took hours. But the Queen said: ask as many questions as you need. And they responded to everyone.” Finally, it was Anton’s turn to speak. He said: “We owe it to our loved ones to see this through to the acceptable end.” The meeting ended with these words. Perhaps because of this phrase he uttered at that meeting, Anton still actively cooperates with the MH17 Disaster Foundation. Every year, he organises a commemoration day for the victims. He has attended all 67 court hearings. Anton considers it his mission now.

Despite getting good professional help, his wife Hilda could not recover from this loss neither physically nor mentally. Anton says she was completely disoriented. She died in 2019. Since then, Anton has lived alone. Thankfully, he has another son and two grandkids who live nearby.

“I want to show you something very important,” Anton says and practically runs up the stairs as if he were seventeen. He comes back a minute later with a small dark blue kids’ backpack. I see the name of his six-year-old grandson who died in the crash written on the backpack and understand what it is. “It fell from 33,000 feet and stayed completely intact,” Anton says. “There’s not even a scratch on it! Unbelievable, right? Even the hand luggage tag is still there. And all the stuff inside was intact — books, pens, pencils… I was so happy! It’s such a treasure for us!”

Anton shows the surviving hand luggage tag on the backpack. Photo: Ekaterina Glikman

Soon after the holidays back in 2014, Remco was supposed to start school. His grandma Hilda spent many evenings with the backpack, stroking it, even talking to it at times. Last September, Anton brought it with him to a court hearing to show it to the judges when he took the stand.

Eindhoven, where Anton lives, is the fifth largest city in the Netherlands. It is called the City of Light: the world-famous Phillips company was established here. During WWII, most of the city was bombed, so now it looks very modern, with wide streets and high-rise buildings. It used to be the city of tobacco and textiles. Now, it is considered a city of high technology and IT. ASML, one of the world’s leading producers of photolithography systems that are used to produce computer chips, is based here. Its equipment is banned for political reasons in China, and now in Russia as well.

Anton’s son Oscar worked at Philips Medical Systems. He was responsible for purchasing medical equipment parts. His wife Miranda was an accountant.

Anton started his career as a primary school teacher. Hilda was a teacher too, but at another school. He was later promoted to headmaster and, even later on, took up a position administering the education system. For many years, Anton cooperated with the Dutch Ministry of Defence: he was developing education projects for army schools. The man travelled a lot, working on similar projects in Germany, Belgium, Hungary, France, the UK. “They still contact me for help. I’m surprised: I’m an old man. But they tell me: you have a lot of experience. And I keep working. So, if I don’t have any plans for the day in my calendar, I feel uncomfortable,” he says.

Oscar, Remco and Miranda. Photo from the family archive

Eindhoven is located in the south of the Netherlands. About 50 victims of the MH17 crash were from southern provinces. The first remains of the victims were delivered here, to Eindhoven Airport, from Ukraine. The relatives were waiting for the plane on the tarmac. After the two planes carrying the remains had landed, the crew formed a line on the tarmac.

The relatives came to greet them and thank them for transporting the bodies of their loved ones back home. Anton was there too. He suddenly heard: “Anton! Hey! What are you doing here?”

“Right as he said it, he understood everything. I looked at him and asked: “Christiaan, you’re the pilot of this plane?” He nodded. And then we couldn’t say anything to each other. We were just standing there speechless. Several months before that, this pilot was showing me the planes at a small army base in Hungary. And now he was the one who delivered my kids who were killed to me,” Anton recalls.

A long convoy with dozens of hearses left Eindhoven for the Hilversum military base, where the bodies were identified. People stood in line along the route, throwing flowers and applauding. “Holland has shown its quality,” Anton says.

There were 11 more deliveries of remains to Eindhoven. Anton was there for each one of them.

The main thing that Anton expects of the court proceedings, the main thing he hopes for is that the judge will determine the degree of Russia’s involvement in this tragedy. “Russia — or should I say, the Russian government — behaves in a peculiar manner: they are accusing the world of exactly the thing they are doing themselves. And they don’t want to take one iota of responsibility. They deny everything.”

In January of this year, Anton met a delegation from Russia at a court hearing in Strasbourg for the first time. “They told me they are sorry. It was very good to hear this from Russians, especially in public. But at the end, they said: if you want contributions, you need to start legal proceedings in Russia. I asked those sitting beside me: did I get that right? I didn’t even know how to react: to applaud or to laugh. Who would start the proceedings in Russia? Nobody, of course! Because you know the results in advance! We only hear the voices of accusers in Russia. And it’s unclear where the truth is there. So, I feel very bad for regular Russians. The things the Russian state is doing to its own citizens! I feel very sorry for Navalny who was sent to jail. It’s unbelievable to me. Authoritarianism and no rights for the people. And the people… they survive. Here in the Netherlands, we have a rich life: we have freedom of speech. We can express our opinion absolutely freely, and no one sends us to jail for that,” Anton exclaims.

He thinks that the MH17 tragedy should have been a wake-up call for Europe, “but the European states decided that those were their local issues, they would deal with them themselves, and they stayed asleep: I blame all NATO states for this.”

Over the past eight years, so much has happened in Anton’s life that he wanted to share with his eldest son. The fact that he cannot do that torments him. One time, his youngest son told him: “All my life, I thought that Oscar and I, the two of us, would take care of you when you get old…” When Anton thinks about that, he gets angry.

But recently, he has found a new person to talk to: a woman born in Russia, whose parents are now in Ukraine, lives just a house away from Anton. She worries about her family a lot. Anton says that they have a lot to talk about now.

The fifth story

Silene Fredriksz-Hoogzand and Rob Fredriksz

Rotterdam, province of South Holland

The victims: Bryce and Daisy

The house of Silene and Rob Fredriksz looks like a shrine: no matter where you look, you will find photographs of their only son Bryce and his girlfriend Daisy. They look young and in love. He was 23, she was 20. “Forever together,” reads the inscription on a cross stitch portrait of the couple.

“It’s been eight years already, but it feels like yesterday,” Rob says. “Every day, every hour, we remember.”

“Their room is still the same as it was. I can’t throw out their things. I just can’t,” Silene cannot hold back tears.

Silene and Rob Fredriksz. Photo: Ekaterina Glikman

She remembers 17 July 2014 very well. Silene was at a barbecue with her colleagues. Her phone was on silent. When a colleague handed her the phone saying “Your daughter”, the first thing she thought was: her husband is having a heart attack or something happened to the kids. Her daughter could not speak. Then the husband picked up the phone. He was yelling: “The children! The plane crashed! You need to come home!”

“They couldn’t reach me for an hour and a half! I was the last to find out,” Silene says. “My colleagues took me home. The house was full of relatives already. And our world fell apart. That’s it. Your heart is broken. You can’t think of anything. You can’t do anything.”

“Does it get better as the years go by?” I ask. “It doesn’t get better. It’s different,” Silene says. “We are stronger now. But the pain and the anguish don’t go anywhere.”

Silene is 59. After the tragedy, she had trouble focusing on things. She had to find an easier job and cut the working hours to 15 a week. Her husband Rob was already retired at the time of the crash. He is now 74. At times, both of them go silent and get a faraway look on their faces. They pause for a while, and when I start thinking that they are no longer here, one of them comes back and continues their story.

The only body parts they received are the left foot of their son, burnt to a crisp, and a piece of his girlfriend’s femur. It is very important to them that both of them are identified.

“We think that Russia is to blame for this tragedy, Putin is to blame,” Silene says. “But from the very beginning, there have only been lies, disinformation, denial, and lack of cooperation from Russia.” “If Russia had said from the very beginning: we are sorry, it was a mistake, we did not want this — we would have accepted it,” Rob says. “But all these lies are driving us crazy. Tell us the truth!”

A small group of relatives, which includes Hans de Borst, Silene, and Rob, puts out 298 white chairs in front of the Russian embassy every year in June. The placement of the chairs mimics the airplane seating layout: two aisles and three rows of seats (two seats by the windows and five seats in the middle). This is a very powerful statement: without words, it triggers an emotional response for everyone who sees it. Well, everyone except the Russian Embassy in the Hague, which has ignored this display for eight years in a row.

In the first couple of years, the relatives of the victims also knocked on the embassy door to deliver a letter written by the families of those killed in the crash. But no one came out to collect it. “They only looked at us through the blinds,” Rob recalls. Then the relatives left the letter in the mailbox.

However, there was one response letter after all. Six years ago, the relatives of the victims sent an open letter to Putin. They got a response: not by the president, of course, but by someone from Almaz Antey, a corporation that designs Buk missile systems, which took down MH17. An embassy attaché delivered the letter to them in person.

“It was a very sad-looking young guy. They sent him to us as the messenger,” Silene says. “He said that he had waited half an hour in the car in front of our house, because he didn’t have the courage to knock on the door,” Rob recalls.

“What was in that letter?” I ask. “Bullshit!” Silene says. “That the Buk was Ukrainian and Russia has nothing to do with it.”

Silene says that she will not give up trying to get Russia to admit the truth while she is alive. “We are not angry at the Russians. We are angry at Putin,” Rob stresses.

Bryce and Daisy. Photo from the family archive

“It’s so important to know the truth,” Silene says. “What happened? Who did this? Why did they press the button? Buk was operated by a Russian team, they were well-trained. How could they think that it is not a civilian plane? I don’t understand. I don’t believe it. It is very hard for me to believe that this was done by mistake. The answers to our questions are in Russia.”

“I have questions for Ukraine, too,” Silene adds. “They should have closed the sky. There were active hostilities there.” “But they didn’t want to lose money,” Rob suggests.

Five members of their family took the stand at the court hearing last September. Each one was given the opportunity to speak: Rob, Silene, their daughter, and Rob’s daughters from his first marriage. What did they talk about? They said that their family is now broken. Each one of them suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder. Their daughters have panic attacks. All of them feel empty. Rob says that there is no future for him anymore. It is as if he lives with a life sentence hanging over him. Silene explained how much they all need to get to the truth.

It does not matter to them anymore whether anyone will go to jail for what they did or not. They trust the Dutch justice system and they will accept any verdict of the judge.

Unlike many others, they were not surprised by what happened this February. “We’ve known for all those eight years what Putin is capable of,” Silene says. “The war in Ukraine never ended, it’s been going on since Crimea. Now he is doing it openly, that’s the only difference. He is capable of anything. I don’t know if he’s gone crazy or… He could have been stopped, but no one wanted to do it.

And now… I don’t know what will happen next. You don’t know. No one knows. But it’s bad for everyone: the Ukrainians, the Russians, the Europeans. I think he will destroy Russia in the end.”

Rotterdam, where the Fredriksz family is from, is a major European port. Before the war, 13% of cargo that went through the port was from Russia: crude oil, oil products, coal, steel, aluminium, nickel. The volume of trade between Europe and Russia through Rotterdam amounted to $300 bln a year. Now, the EU sanctions introduced over the Russian invasion of Ukraine are gradually entering into force. The volume of cargo delivered from Russia is starting to go down. The trade is wrapping up.

There is a banana tree growing in Silene and Rob’s tiny garden. Bananas do not grow on it: the tree is purely decorative. It also makes Rob remember Indonesia, where he was born, and where Bryce and Daisy headed for their holidays eight years ago, on 17 July.

“Every time we see a plane in the sky we think of them,” Rob says. “Do you fly?” I ask. “We waited several years and then got on a “test flight” to Spain with a group of other relatives,” Silene responds. “It was difficult, even horrible. We cried on the way back, but we did it.” Four years ago, they finally flew to Indonesia. There, on an island that they visited together with Bryce when he was little and that he called “heaven on earth”, they scattered some of his ashes.

They desperately wanted to visit the crash site. But it was impossible eight years ago and it still is now. They hope that if they cannot make it, their ancestors might be able to visit the place when it is safe. “What for?” I ask them. Silene responds: “Many of Rob’s family members were killed in Indonesia during the Second World War. His parents couldn’t visit it then, but we came there afterwards. We brought flowers there. It’s important that someone from our family brings flowers there. Brings peace. Brings love.”

Monster — Maarssen — Bolsward — Eindhoven — Rotterdam,

The Netherlands

The interviews were edited for clarity

This article was written with support from MediaNet

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]