There are over a million Ukrainian refugees in Russia. Svetlana Gannushkina, chairwoman of the Civic Assistance Committee (this organisation is on Russia’s foreign agent register), says that the figures may vary depending on who is keeping count.

Ukraine suggests that about 1.2 million people have left for Russia. According to the UN, there are 1.4 million refugees currently in Russia. The Russian Defence Ministry offers a figure of 2.2 million. Russian lawmaker Konstantin Zatulin said that the country “is fighting for these migration flows”.

Only 304 people in Russia have an official refugee status. In the first quarter of 2022, only two people were officially recognised as refugees. It is simply not in the government’s interest. Firstly, people with a refugee status are eligible for all benefits and pensions that Russian citizens have. Secondly, how can there be refugees from “liberated territories”?

The majority of Ukrainian refugees in Russia are granted “temporary asylum” instead. Or worse, they do not have any official status at all.

The refugees get a bed at temporary accommodation centres, where they are also given food. But there is nothing else there. People need a change of clothes, shoes, shampoos, combs, toothbrushes and so on. They do not have the money to buy these things. Without a Russian citizenship, the refugees cannot find a job or apply for social benefits. Applying for Russian citizenship costs 6,000 rubles (€100), a sum that the refugees often do not have. In any case, it takes the government several months to process the application.

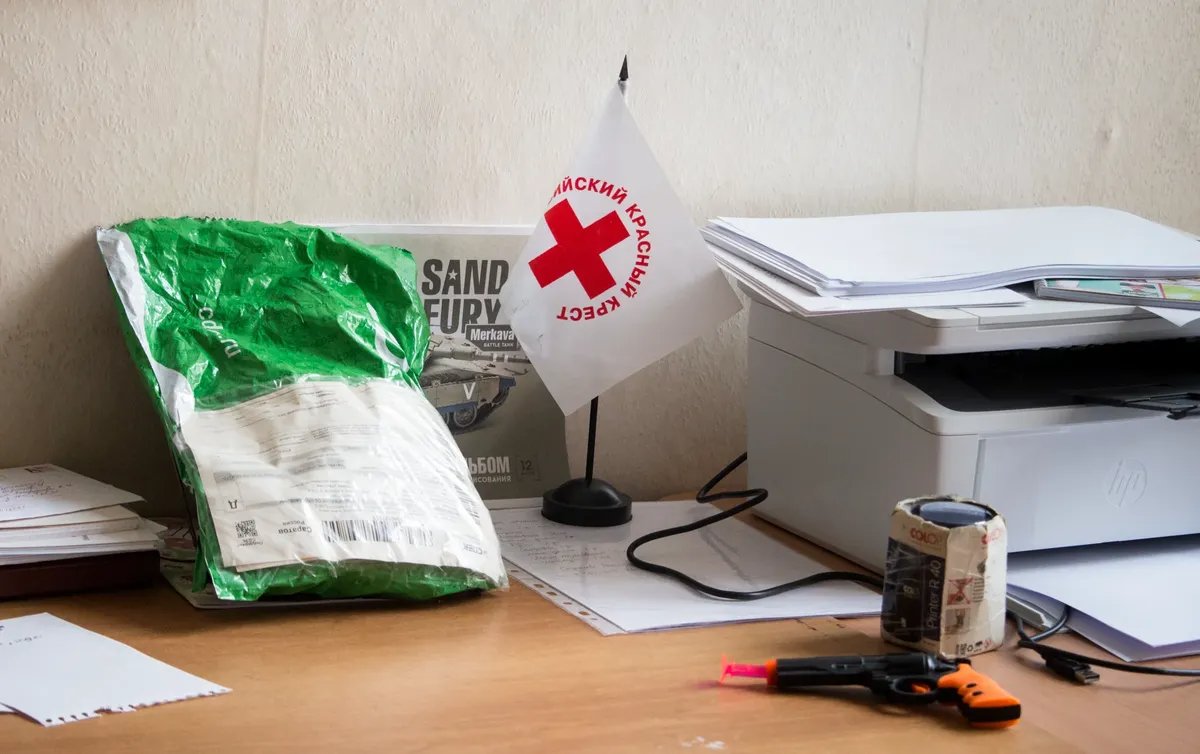

The Red Cross at a standstill

A white banner with a red cross can be seen at the end of the hall. The lights are out, the walls are covered in cracked plaster. The regional office of the Red Cross is the only place in Russia’s Saratov region that collects humanitarian aid for Ukrainian refugees.

Everything is stored in the rooms down the hall: cleaning products on the right, food and clothes on the left. “We attended the refugees at reception. Volunteers asked them questions, filled out a request and got the things they needed from the warehouse. We tried to make our food packages bigger and asked refugees to bring large carrier bags,” chairman of the Saratov Red Cross office Alexey Zakharov says. “Not everyone can list off everything they need in these conditions. It’s hard to imagine: a regular person who lived a good life was suddenly left with nothing. They don’t even have their own toothbrush.”

Zakharov was surprised by how high the demand for hand cream and panty liners was. House slippers were also an in-demand item: in the spring, many refugees had to wear shoe covers and felt boots. They had no shoes that they could use inside.

The Red Cross got an office with no electricity or central heating from the Saratov government in February, when the first refugees from Donbas arrived in the region.

On the wall, there is a calendar for the year 2009 with a picture of cute dogs. The place has been abandoned since then. Zakharov, a dentist who heads a small private clinic, took out two trucks worth of trash and installed plastic windows at the office. He also bought a pickup truck to transport humanitarian aid to temporary accommodation centres. The volunteer paid for the petrol himself.

The local youth ministry promised to send in volunteers to the Red Cross office. However, people usually left after one day. “About four or five people remain after these few months. They’re just as crazy as I am,” Zakharov laughs.

Alexey Zakharov. Photo by Matvey Flyazhnikov, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

The expected level of horror

“What does a person who gets a job at an international organisation that has been helping the sick, the poor and the hungry for 150 years expect? They think that they’ll get a nice uniform, be put on a helicopter with a red cross and sent to save the children in Africa,” Zakharov says. A colleague invited Alexey to the Red Cross in 2016. Alexey, a young successful doctor, found out a lot about his home city. The local Red Cross office had their hands full even before the “special operation”: the Saratov region is not a well-off one: 44% of its residents earn less than 19,000 rubles (€320) a month.

“One time we got a call from a man, a father of ten children. He said that his nine-year-old daughter had broken her leg, got sent to a hospital and there was no one to take care of her: he had to work and his wife couldn’t leave the other children,” Zakharov recalls. Alexey’s wife agreed to visit the hospital to help out. “What I saw there shook me to my core: the girl weighed just 16 kilograms. She was bald: they had to cut off her hair because of lice. She devoured the hospital rice in one go. But she was an outgoing and fun girl. She said that she had stolen a chicken and was running away with it when she fell,” she says.

Alexey’s wife and her friends took turns staying at the hospital. They gave the kid food and clothes. “We asked the children’s right commissioner’s office to find out whether everything was okay in the family. They told us that they’re a normal family, the children even do afterschool programs. It’s just that they are poor.”

“It’s not that I’ve gotten used to it, but it’s not unexpected to me now,” Zakharov says of his experience at the Red Cross. Before the “special operation”, the office collected and delivered gifts for orphanages and retirement homes,

clothes for families with many children, food for bedridden people with disabilities and low-income seniors.

“People I know often think I’m crazy. They ask me what I’m doing this for,” Alexey says. “I tell them: the problem is that we don’t want to see what’s happening around us. Everyone’s got their own problems, everyone has bills to pay. And yet, there are people right beside us who really need our help.”

When the photo-op is over

In March and April, scores of people came to the Red Cross to help the refugees. “The railway, the nuclear station, the gas workers: companies visited us one after another, put up their logos and took pictures with them. Regular people brought us stuff, too: from worn jackets to microwaves,” Alexey recalls.

Now, the sun-soaked warehouse that used to store cleaning products and personal hygiene items is completely empty. In the opposite room, there is a pile of stuff that no one wanted: a lilac jacket, striped trousers, a stuffed pink mouse, a bent puzzle box.

“People stopped bringing humanitarian aid to us very suddenly, as if on command, in late April. Maybe we had run out of organisations that needed a photo-op. Maybe people just got tired of it mentally: I bought 100 cans of meat, I did everything I could, alright, I don’t want to think about it anymore. Maybe the TV reports from Europe [shown on Russian TV] are working: they show people how bad and greedy the refugees are, how they’re smashing everything up. I don’t know if it’s actually true and what they are showing it for,” the Red Cross worker says. “I practically never watch the news myself. I don’t even have a TV at home.”

Photo by Matvey Flyazhnikov, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

In May and June, the Red Cross handed out the supplies it had stored up: over 30 tonnes of stuff. Now, there is nothing left.

The chairman of the Red Cross office says that up to 60 people call them every day: usually refugees that came to Saratov on their own to live with relatives or rent a flat. Zakharov says there is about a thousand of them in the region. Unlike those living at temporary accommodation centres, people who live on their own need food the most. They need grains, pasta, canned goods.

“Right now, I’m telling people: I don’t have anything, call back next week. What will happen next? I don’t have an answer. I am doing everything that is in my power. We tried to collect humanitarian aid at a local festival. They brought us two packs of pasta and two bottles of water,” Alexey says. He also wanted to find out whether the local ministry of social development could help. But they called him back to ask: “Another 360 people have arrived, can you help us?”

A hero of the ‘Russian world’

“Please, no photos and videos. Don’t include my surname. What if the khokhols (a Russian ethnic slur for Ukrainians — translator’s note) find me?” says Oleg, a former militiaman of the self-proclaimed Donetsk “people’s republic”, also known as the “DPR”. He postponed our meeting twice, and then asked us to hold our interview over the phone. “It’s better that I don’t be seen.”

Oleg has severe post-concussion syndrome. He does not have a right eye; the left eye does not see well. He walks with a cane due to spinal injuries. The man often switches to Ukrainian while we talk. He suddenly asks me: “What year is it?”

Oleg was born in 1966 in near Russia’s Saratov. “When I was two, my dad took me to Horlivka. They paid the miners very well there.” Oleg studied at a Ukrainian school; he knows the language as a native speaker. He completed his two-year conscript service with the Russian Airborne Forces in Novorossiysk and then found a job as a construction worker. “I built the settlement near the Oktyabrskaya mine in Donetsk. In Kharkiv, Kremenchuk, Melitopol. We built such a great holiday base in the Carpathians! All our miners used to go there. 1,200 cottages in Ilichevka (now Ilichanka — translator’s note) in the Odesa region. I don’t know if they’re still there now,” Oleg recalls.

His family lived in Hrushivka, not far from Horlivka: “It was a nice and cosy miner town. People went to work at the mine, and their families lived there. They’re saying it’s gone now.”

His wife’s name was Elena. “Olena in Ukrainian,” Oleg repeats her name several times, and then stops himself. “I’m not going to tell you anything. I don’t want to rub salt into the wound. She was killed in 2014.”

Oleg joined the “people’s militia” in the “DPR”. According to various estimations, there were over 20,000 people serving in “the people’s militia” until the “special operation”. There was no conscript service in Donetsk, everyone signed a contract. The servicemen were paid from 24,000 rubles (€400) a month, about the same as the average salary in the “DPR” and its neighbouring Luhansk “people’s republic”, or the “LPR”. The requirements for contract service are very lax here. People from Russian regions that could not sign a contract with the Russian army due to their criminal record or health problems easily got accepted into the “people’s militia”.

Oleg says that in 2014, he was concussed and sent to a hospital in Russia’s Volgograd region. He was then transferred to a hospital in Saratov to continue treatment. It was reported in the Russian media that fighters of the “DPR” and “LPR” had undergone treatment at local hospitals, although they are neither Russian citizens nor servicemen of the Russian army. For example, a VK group dubbed Help and Support to Novorossiya (or New Russia, this is how the Russian propaganda refers to Ukraine’s southern and eastern regions — translator’s note) talks about the treatment of injured militiamen in 2017. BBC Russian told the story of a 20-year-old resident of Donetsk, a citizen of the “DPR” who was taken to a hospital in Russia’s Rostov after an injury near Kherson. According to Russian law, non-Russian citizens who do not have access to free healthcare can only receive emergency medical aid.

Oleg returned to Donetsk after he had completed his treatment. He wanted to apply for Russian citizenship, but he did not have enough money for a bribe, the man says. In the autumn of 2021, the militiaman was sent to Saratov once again with a spinal injury. He decided to stay in Russia. He was offered to apply for citizenship under a procedure for citizens of distant foreign countries. He filed a complaint with the governor’s office and found out that he can apply for expedited citizenship under a procedure available for Ukrainian, Belarusian and Kazakh nationals since 2019: they do not need to live in Russia for five years, have a certain sum of money on their bank account or take a Russian language test. But even the expedited procedure takes six to seven months and requires money.

“You need 5,000 [rubles, €85] for the medical examination, 2,500 [rubles, €42] for the translation of your Ukrainian passport. The translation needs to be notarised. You also need four pictures. The fee is 3,000 [rubles, €51],” Oleg says. “Where would I get this money? I borrowed it from my friends.”

In 2021, 735,400 people were granted Russian citizenship, over half of them were Ukrainian citizens. Experts with the Civic Assistance Committee note that this is a record high figure. However, in the first quarter of 2022, 12% fewer foreigners were granted Russian citizenship than in the corresponding period of 2021.

Oleg was supposed to receive his Russian passport in May. Shortly before that, he came to the train station to meet another group of refugees. “I don’t know where I lost my Ukrainian passport,” the man sighs. He had to re-apply for citizenship because of that.

Saratov employers do not want to hire foreign citizens: they have to report that they hired a foreign national to government bodies within three days, otherwise they will get fined.

Oleg found a job as a guard without an official contract. He could not apply for benefits as a disabled person without a citizenship either. The man says that he needs spinal and eye surgery. Without a Russian passport, he cannot get free healthcare.

Oleg is not the only Ukrainian national in this situation. “There are 18 guys from our battalion with light injuries,” the former militiaman says. The “DPR” patients say that they were discharged from hospitals with a bag of pasta. They moved to a dorm on the outskirts of the city. Some of the militiamen went back home.

‘The war changed all our plans’

“We’re not homeless,” Viktoria Alekseevna stresses. She is a professional seamstress. Viktoria Alekseevna used to sell women’s clothing at Mariupol markets. Her parents moved to Mariupol during the Soviet era from Russia’s Far East. They worked at local steelworks. Up until February 2022, Viktoria Alekseevna lived in a three-bedroom flat in the centre of Mariupol. “The flat was renovated, we had all household appliances, I prepared everything to spend my retirement there. The war changed all our plans,” the Ukrainian refugee says.

Photo by Matvey Flyazhnikov, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

The 62-year-old woman spent two months in a basement. She only went outside to get food from her apartment: she stored up on sugar, grains and canned food. One time, “a man with a large beard” knocked on the basement door: her district was occupied by Kadyrov’s (Ramzan Kadyrov, the head of Russia’s Chechnya — translator’s note) forces. The first thing Viktoria Alekseevna did was ask for a phone to call her daughter.

An acquaintance that had a car and was taking his mother out of Mariupol agreed to give them a ride. They spent nearly 24 hours waiting on the border. On 1 May, the women successfully went through a Russian filtration camp. After that, they drove to Russia’s Izhevsk, where her ex-husband’s brother lived.

Viktoria Alekseevna took 19,000 hryvnias (about €640) with her: that was all she had saved up. She came to a Russian bank to exchange the money, where she was told that they can only exchange 8,000 hryvnias (€270) per person at a fixed exchange rate, only after the refugees receive the 10,000-ruble (€171) payout announced by the Russian president.

Refugees can apply for this payout through several Russian regions: the Rostov, Belgorod, Kursk, Voronezh, Bryansk, Stavropol and Krasnodar regions, as well as Crimea. The refugees that ended up in the Saratov region must send their applications to the Krasnodar region. It takes several months to process their documents.

According to official information, Russia has already spent over 4 bln rubles (€68.5 mln) on payouts to the refugees. This figure is set to increase: over 624,000 people have applied for the benefits so far.

In Izhevsk, Viktoria Alekseevna and her daughter were granted temporary asylum. According to the Civic Assistance Committee, in 2021, 19,800 people were given temporary asylum in Russia (including 18,300 Ukrainians). In the first quarter of 2022, 4,700 people were given this status, over 95% of them are from Ukraine. According to Russian law, people granted temporary asylum can work and get free healthcare on an equal basis with Russian citizens. In actual fact, Russian regional officials do not know what to do with foreigners that were granted this status.

“The woman working at the passport office saw our temporary asylum papers and sent us to her boss. She said she doesn’t know what they mean. We waited in line to see the boss. She told us that this is not a document,” Valentina, Viktoria Alekseevna’s cousin, says. Valentina lives in a small town in Russia’s Saratov region. Her relatives from Mariupol came to live with her from Izhevsk.

Valentina decided to get Viktoria Alekseevna and her daughter a temporary residence permit. “They sent us to a commercial firm to fill out the forms. My cousin told them that they speak Russian, they can fill them out themselves. But they were adamant that we had to pay. They charged us 300 rubles per each form and an additional fee for photocopies.”

Valentina was warned that the officials might visit her flat to see if her relatives really live there. If they leave to another town to look for a job, Valentina may be faced with criminal charges for falsified registration of migrants. She could be fined 150,000 (€2,500) rubles or sentenced to three years behind bars.

Photo by Matvey Flyazhnikov, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

Employees of the local job centre told them that refugees can only work illegally. Valentina tried to prove to them that it is not true, as the document explaining the rights of people granted temporary asylum was on their boss’ desk. But the official did not listen to them.

The refugees were promised pillows and blankets at the centre of social services. “The boss called all the local organisations asking for help, but no one wanted to help,” Valentina says.

Valentina works as a boiler house operator. She earns “a good salary” for their town: 20,000 rubles (€342). She spends half of it to pay for her daughter’s classes. “I realise that no one except me can help my family. But my salary won’t even be enough to feed and clothe them, even feeding them is hard enough.”

Valentina managed to get an appointment with a local MP. The refugees were then provided accommodation at an apartment that had stood empty for years. “Now we have our own room, there’s hot and cold water. After what happened to us, I didn’t even believe that it could happen. We didn’t think anyone was going to help us,” Viktoria Alekseevna says.

The refugees want to go back to Mariupol by the winter. But their friends who remain in the city tell them that “it smells of corpses on the street, there is nowhere to live.”

‘I don’t see a future for my children there’

By order of the Russian government, 1,300 temporary accommodation centres were established in Russian regions that can take in 96,000 people. The Russian state spends 1,328 rubles (€22) a day to accommodate one Ukrainian refugee (including 415 rubles, or €7, for food). The Russian government allocated a total of 11.8 bln rubles (€202 mln) to help Ukrainian refugees. According to The Moscow Times, since February, Russian regions signed over 600 government contracts on the transportation, accommodation and food for the refugees to the tune of 1 bln rubles (€17 mln). The federal government must reimburse this sum to the regional budgets. So far, the government reimbursed less than 500 mln rubles (€8.5 mln), The Moscow Times estimates.

There are four temporary accommodation centres in Saratov. The first train with 1,300 “LPR” evacuees arrived in the region on 21 February. In the spring, refugees from Mariupol and the Kharkiv region were sent to the Saratov region as there was not enough place for them at the accommodation centres in southern Russia. There will likely be even more people sent to the region. According to governor of Russia’s Rostov Vasily Golubev, every day, from 12,000 to 20,000 people arrive in Russia from the “LPR”, “DPR” and Ukraine.

Elena and her daughters lived in Kirovsk, known in Ukraine as Holubivka, a town about 40 miles way from Luhansk. “It’s a small town, 30,000 people live there. The mines were operational. There was a park for children,” the woman recalls. In 2014, the city was shelled, but “not much”, Elena says. She was not in Kirovsk at the time, but not because of the hostilities: her elder daughter needed surgery.

Elena has a degree in teaching Ukrainian language and literature. After “LPR” was formed, she started teaching Russian instead.

On 19 February, Elena came home from work and lied down for a nap. The children were staying at their grandmother’s. Suddenly, she got a call from her sister. “Are you sleeping? Pack up your things, we’re leaving!”

The city announced an emergency evacuation. “I packed up the first things I saw: warm sweaters, tights, toothbrushes. I only packed one bag,” the woman recalls.

Elena’s mother refused to leave: she did not want to abandon her cows and garden. Her sisters and their children boarded an evacuation bus. On the way to Luhansk, residents of neighbouring villages joined them. They spent the night at a community centre in Donetsk. “We thought that we were leaving for three days, ten days at the most. We were planning to wait it out somewhere nearby, in Rostov. Then they told as at the Likhaya station that we’d be sent to Astrakhan. Then they told us we were going to Volgograd. We only found out we were going to Saratov when we were on the train.” Elena did not know anything about Saratov: “I have no relatives in Russia. My sister and I are on our own. We have each other.”

The refugees were taken to a health resort on the Volga River. When the holiday season began, they were transferred to a smaller resort that used to belong to a now-bankrupt chemical plant. A total of 170 people from Donbas and Mariupol live there now. The seniors who were left without their retirement benefits have it the hardest.

“We need summer clothes and personal hygiene items: deodorants, shampoos, diapers,” Elena says. Some families brought their pets with them, so they need cat and dog food. Elena has been tasked with keeping note of the humanitarian aid the Luhansk refugees need. However, local residents do not donate food and clothing to the refugees that often.

Elena was offered a job at a local social service centre. She is a Russian citizen: she got a Russian passport several years ago as a resident of the “LPR”. The problem is that she left her teaching diploma in Kirovsk, and without it, she cannot find a job as a teacher.

Elena’s mother tells her over the phone that “it’s never quiet at home”: the neighbouring village of Stakhanov, known in Ukraine as Kadiivka, located about six miles from Kirovsk, is shelled every day. The frontline is about 20 miles away.

The teacher plans to stay in Russia. “I don’t know how fast they’ll recover Kirovsk. My children are getting older. I don’t see a future for them there.”

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]