In 2021, Muratov and a Filipino journalist Maria Ressa received the Nobel Peace Prize for “the efforts to safeguard freedom of expression, which is a precondition for democracy and lasting peace.”

Muratov was awarded the legendary gold Nobel medal as part of the prize. Soon after the war in Ukraine broke out, he decided to auction it to assist displaced Ukrainian children.

According to the UN, the Russian invasion has caused “the fastest and one of the largest forced displacement crises since World War II.” Approximately 16 million Ukrainians had to flee their homes since the hostilities began.

“More than 3 million children saw their education suspended — an entire generation of children whose future hangs in the balance. All over the country, hundreds of thousands of people do not have access to water and electricity, and millions do not know where their next meal is coming from,” Amin Awad, UN crisis coordinator for Ukraine, said in a statement.

Those close to Dmitry Muratov told Novaya Gazeta.Europe that “he couldn’t wrap his head around the fact that two-thirds of Ukrainian kids had become refugees.” Then, on March 22, he made a decision to offer up his Nobel medal, “the most treasured and valuable thing that he had” to aid war victims.

“The world no longer has alien refugees,” the Novaya Gazeta editor-in-chief said earlier.

The Nobel Committee and the newspaper’s staff unanimously backed Muratov in his decision.

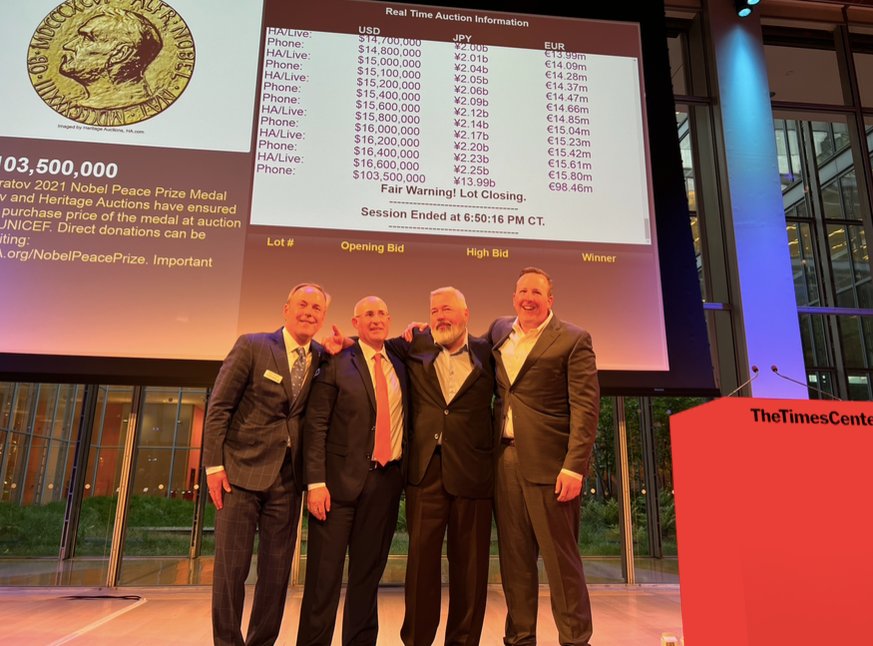

The auction was launched online by the US Heritage Auctions on 1 June, International Children’s Day, and closed on 20 June, World Refugee Day. All proceedings from the sale — the record-breaking $103.5 million — will go to the UNICEF humanitarian mission assisting Ukrainian child refugees and their families wherever they may be, in the EU, Ukraine or Russia.

Russian journalist Elizaveta Kirpanova covered the historic auction in New York City for Novaya Gazeta.Europe.

***

The Times Center that hosted the auction is nestled around skyscrapers in the very heart of Manhattan. The same building houses the office of The New York Times, one of the most renowned American newspapers. There is certain symbolism to this, it seems.

Guests start gathering around cocktail tables in the hall by 5 p.m. The women are dressed in gorgeous gowns of every colour imaginable and heels, while the men donned stylish suits and ties. Servers are skillfully maneuvering around people to bring out drinks and snacks. The sounds of piano are filling the hall.

Photo: Elizaveta Kirpanova

The sole auction lot, the gold medal with the engraved profile of Alfred Nobel, solemnly rests on a round table in the corner next to a bouquet of white and purple flowers. It is guarded by two security officers. You can take a picture of it but no touching is allowed.

In the centre of the hall, I come across two women dressed in all black, Polina Buchak and Marina Prikhodko. Polina is wearing a small brooch made in blue and yellow. They are Ukrainian activists who work for “Razom”, a non-profit organization that provides humanitarian assistance for Ukraine, particularly purchasing medical equipment, medicine and evacuating children and their families to safer regions. Moreover, the non-profit extends grants to small Ukrainian organization so that they can supply food to people and shelter them.

“The goal behind this auction is to unite everyone to help Ukraine,” Marina says. “We support Dmitry Muratov and hope that others will follow suit.”

“Also, we are Ukrainian women and just could not miss the chance to attend this event,” Polina adds.

Dmitry Muratov enters the hall 30 minutes after the banquet started. He is immediately swamped by reporters with cameras. Muratov’s child Fin asks journalists to turn off bright flash. In early April, the Nobel prize laureate was attacked in the broad daylight — someone splashed red paint laced with the solvent acetone on his face while aboard a train in Russia. The attacker shouted, “here's to you for our boys.” Muratov was later diagnosed with eye burns so it now hurts him to look at bright lights.

Photo: Elizaveta Kirpanova

Few minutes later, Muratov walks into a separate room to rest before the auction presentation. Muratov is greeted there by Robert Wilonsky, communications director for Heritage Auctions, to instruct him about what will happen on stage.

“I’ll just say a few words,” Wilonsky says softly. “The auction will take 15-20 minutes. But this is a historic night and it doesn’t matter how long it will take.”

“Is Zubrowka (flavoured Polish vodka — translator’s note) still going to be on the table after the auction?” Muratov responds.

Wilonsky laughs. “Are you having vodka or whiskey? The chilled vodka will be next to the stage.”

“Then you can say more than ‘a few words.’”

Meanwhile, more and more people are arriving at the hall. According to the auction team, around 120 people attended the historic event.

Igor Shneyderov, a likable man in glasses and a grey shirt, is among them accompanied by his wife Larisa. He was born in Kyiv but has been living in the US for more than 40 years.

“I am from the collectors’ community, I am a numismatist,” he says. “Heritage is a major auction, the top one in America. They are offering up a lot of very interesting lots, particularly the ones linked to Russia and the Russian Empire. So, we are very happy that today’s event is taking place in NYC, the Big Apple.”

“Did you place a bid?”

“I won’t say anything about it,” Shneyderov smiles. “However, there were talks among potential buyers.”

The auction drew in more than just relic connoisseurs, but also New York City intellectuals from very different professions.

Here is Olly (he asked for his surname not to be mentioned) who works in workforce optimization.

“I didn’t know much about Dmitry but knew what had happened to some of his colleagues, like the journalist who was killed in her home (Anna Politkovskaya — Novaya Gazeta Europe). When I learnt that this event was taking place, I wanted to take part in it because I sought to understand how you can support the mission of independent media in Russia. I value freedom of the press. And I wholeheartedly support what Dmitry Muratov is doing now.”

Here are actors Jack and Aiden.

“I think that this is a right message to the whole world — we are here to help Ukraine. Muratov emphasizes that he is doing this for the kids, for their future. It is amazing,” Aiden shares. “I am following the war reports. My family has been donating money to support Ukraine and we have been sending clothes for those who need it.”

“We have also been donating money,” Jack adds. “My family have also participated in the flash mob when people from all over the world were booking flats on Airbnb in Ukraine after the war began to help out those left without any income.”

Photo: Elizaveta Kirpanova

***

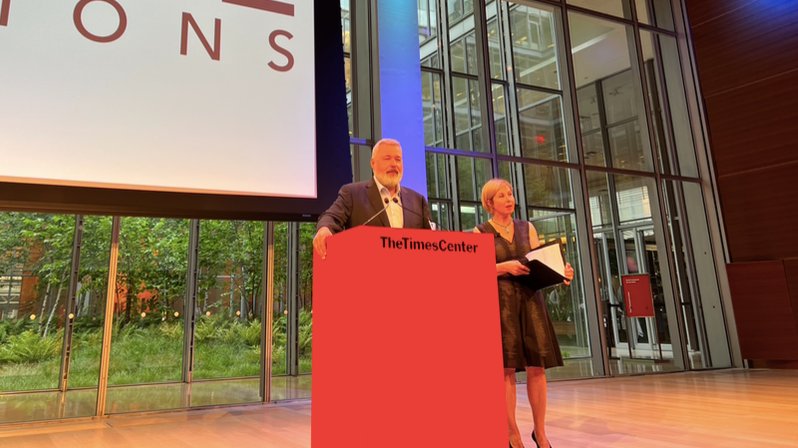

We are nearing 7 p.m., the time when the auction kicks off. The organizers ring the bell to announce it and the guests are slowly moving away from the cocktail tables and closer to the stage. Robert Wilonsky is the first to come out.

“Let me thank everyone who is here and, first and foremost, Dmitry Muratov. When I left the newspaper I used to work for and moved to Heritage, I never thought that I’d be honored to work with the bravest journalist I have ever met.”

“As Alfred Nobel once said, the Nobel Peace Prize is awarded to those who have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind,” Josh Benesh, Heritage Auctions Vice President, continues. “The journalism of Dmitry Muratov is the epitome of this quote. However, what is happening here today goes far beyond this.”

Muratov himself is next to speak.

“Today is World Refugee’s Day and it’s not a celebration. My speech will not be a celebratory one. 16 million Ukrainian refugees. 16 million! 90 percent of the refugees are women and children. Two-thirds of all Ukrainian kids were forced to flee their homes. Ask me when this last happened. And I’ll tell you — never. More than 5.2 million children need urgent aid. These people had their past killed. And now their future is in danger.”

The complete silence in the hall is only interrupted by camera flashes.

“How can we help civilians live their lives? We at Novaya Gazeta decided to give our gold medal to Heritage. Heritage won’t keep a single cent for themselves. It is also a sign of enormous solidarity. I am glad that UNICEF is here. I believe them. Our newspaper believes them. The world believes them.”

The hall erupts in applause.

“All the money that we raise today will go to UNICEF. The funds will be directed to all the countries hosting Ukrainian refugees and children of Ukrainian refugees, Poland, Russia, Germany, Moldova, Slovenia, Hungary and the Czech Republic. If we manage to raise a large amount, UNICEF can allocate some money to help child refugees in Africa and Laos.”

Muratov calls on others to follow in his footsteps and offer up their relics “to aid others.”

It is not the first time he has auctioned something personal and of value. In 2020, Muratov sold an ice hockey stick of legendary Soviet player Valeri Kharlamov from his private collection. He managed to raise $100,000 and sent the amount to a fund organized to pay for an expensive medicine to cure a boy suffering from the deadly spinal muscular atrophy. A few months ago, Muratov auctioned off 39 more hockey sticks from his collection for 55 million rubles (€1 million) to help kids with cancer.

“One child, a refugee from Mariupol, had a prayer,” Muratov continues. “I was told about it — ‘Dear God, help me charge my phone to call my mom.’”

A few people in the hall suddenly snicker.

“I ask everyone in the hall to imagine for a second that this is your child,” Muratov says pointedly. “Our auction does not have a gavel but if it was here, I’d ask for it to drive a nail into the war’s coffin. <…> I’d like to thank the Nobel Committee once again for fully supporting Novaya Gazeta. Thank you. Now, place your bids and let the money flow!”

Mike Sadler. Photo: Elizaveta Kirpanova

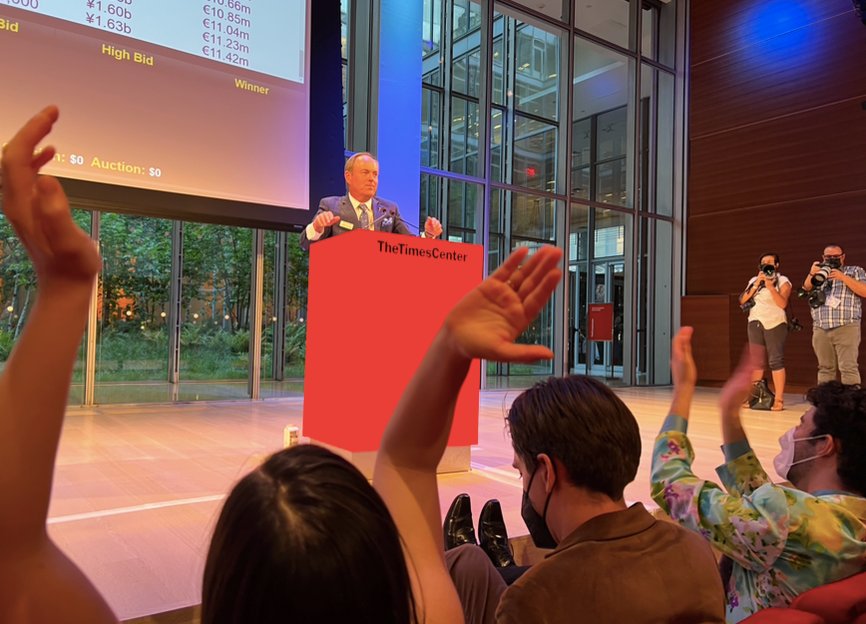

Auctioneer Mike Sadler is next to take the stage to present the lot. Two women who are tracking online offers on the Heritage Auctions website are sitting on the side. Two more members of the auction house staff are sitting in the corner to accept phone call bids. The screen is already showing initial offers, the biggest one being $787,500.

Sadler officially opens the auction. He resembles a conductor, only difference being that he is in charge of the white paddles that are raised practically every ten seconds. In the first minutes, the offers go up by $50,000. However, it all changes when the bids start exceeding $1 million. The amount on the screen changes to $2 million in the blink of an eye. The hall greets this development with a round of applause.

Muratov, who is still in the hall, is trying to keep a straight face. He is recording the historic event live.

Sadler is very quick but he still cannot keep up with the constant stream of bids. We rapidly reach the six-million mark. The guests welcome each new million with more applause.

“Give me the lucky seven!” Mike insists.

And seven million does appear on the screen after somebody placed a bid by phone.

“Dmitry, are you having a good time,” Sadler laughs.

Not being able to hide his emotions anymore, Muratov smiles and raises his thumb in approval.

When the highest offer reaches $10 million, people in the hall start exchanging surprised looks. However, Sadler is far from being done and puts even more pressure on the bidders.

“This is a lot of money but we are donating for refugees all over the world. One more push, one more push! What are we thinking? What are we thinking?” Mike impatiently asks the Heritage staffers assigned to the phone lines.

We are now past the $15 million mark. The bidding slows down noticeably.

“I need the sweet 16, baby. And yes, I do get it, 16 million. So now what, what have you gone all this way for? What are you thinking? Are they saying ‘no more, no more’ on the phones?”

Suddenly, one of the employees, who was speaking with a buyer on the phone (who will remain anonymous, a regular occurrence at auctions), raises from his chair and names a new price but it is hard to hear anything because of his face mask. The crowd goes quiet and he repeats, “I bid $103,500,000 for the lot.”

The hall gasps in disbelief.

“Is there anyone in this room or the whole world who can offer more? If not, then… Sold!”

Muratov returns to the stage accompanied by thunderous applause and takes a selfie with the screen showing the record-breaking nine figures.

Photo: Elizaveta Kirpanova

***

“Let’s continue,” he smiles and then moves to a separate room to give interviews to reporters.

This is what Muratov told Novaya Gazeta.Europe about the auction and its results:

“Faith in God is a private feeling. It is a private matter for a Jew, a Muslim, a Christian or a Buddhist. When the war broke out and there were almost 16 million refugees, it became clear that people in different countries started applying their faith. They welcome refugees into their homes. They share their houses, money, clothes, warmth, water, firewood, travel cards and pillows from the rooms of their children.”

“I have many famous friends like this all over the world who do these things without going public about it. The state failed to stop the war. But people are succeeding in this. The faith in justice and helping those close to you, sharing everything you have, has amazingly come to the forefront. People suddenly displayed their outstanding qualities. Maybe the humanity indeed is God’s mistake. But at some point, God might think that maybe it is not. Maybe it is not a mistake. Like right now.”

“The main thing for me is not to create symbols or words but to take action which will bring about events. This is what we were coming from when the editor’s office was thinking and discussing what can be done. We decided to make a flash mob out of it. And I am very much counting on it continuing further.”

After our conversation is over, Dmitry is asked to come out to the press to say a few final words.

“Can your deed stop the war and the horror that is taking place now in Ukraine?” reporters ask.

“I am not Macron, Scholz or Biden. We are citizens, not politicians. What can citizens do? Citizens can take upon themselves the things that the state cannot. They can publish free media and help war victims.”

“What are your plans now?” somebody shouts from the crowd just as Muratov turns to leave.

“I plan to have a drink… and go home.”