Viktor, 67, and Gennady, 73, tied to each other with a pair of handcuffs, are forced into a police van. Somehow the two manage to get inside the cage and are now escorted to the local courthouse yet again. Novouralsk, a closed town in Russia’s Ural Mountains, is home to 79,000 people, and they all have different attitudes towards the “special military operation” in Ukraine. Although much of the townsfolk do not support it, only two old men are brave enough to protest against the Ukraine War under the constant supervision from the FSB, Russia’s security agency and the KGB’s successor.

An Unsent Letter

Viktor Kazakov was born in 1954 in Novouralsk. Starting from the 1940s, the Soviet Union’s top scientists were sent into numerous closed towns all over the country and were forced to conduct their research under strict supervision from the KGB and police. Kazakov’s parents hailed from different parts of the Soviet Union and met each other in Novouralsk. Galina, Kazakov’s mother, was born in Dnipro, modern-day Ukraine, and used to be a straight-A school student. She graduated the Moscow State University, the Soviet Union’s most prestigious educational institution at that time, and was “distributed” to a closed city — just like many other graduates of her time. After arriving in Novouralsk, she started her job in a local research facility. Vladimir Kazakov, Viktor’s father, graduated college in Gorky, modern-day Nizhny Novgorod in Central Russia, and was also sent to Novouralsk. Viktor Kazakov’s parents worked together for the Soviet Union’s nuclear project.

“I became an anti-Soviet person in 1980,” Viktor says. “I really loved Vladimir Vysotsky, so I decided to collect his aftermath to save it for the future generations. I started to write down his lyrics on paper, and, in a year’s time, I had a three-volume collection of 400 poems by Vysotsky. I also became friends with some other fans of Vysotsky from other parts of the Soviet Union, and I learned that I wasn’t alone. It was at that time that I realised I couldn’t stand the Soviet regime with all its lies. I was 26 years old at the time.”

Viktor was not accepted as member of the Komsomol, Soviet Union’s youth organisation, because of his long hair and love for Vladimir Vysotsky and The Beatles. His parents were called to see the school principal numerous times as Viktor used to share his liberal opinions with his peers and teachers. “My father would often tell me: think what you say in public. So, I was allowed to say what I think at home, but not at school.”

“Live Not by Lies, an essay by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn really inspired me,” Viktor recalls. “I heard it on Voice of America and used to quote it at school a lot.

The teachers would warn me against doing this, they said someone would report me and my parents would have problems. They would never report me themselves, though. They also hated the regime, like most of the people did at that time. But they were afraid as they remembered what Stalin did to them and their contemporaries.

Now how did I become so liberal you would ask? We had lots of books at home, we all read a lot. My parents would discuss everything that was going on, so I heard it. It’s needless to say that their opinion was very different from what was said on TV and on radio.

Once my mother found a letter that I had written for Voice of America. She was shocked and wondered if I had sent it. I did not send it, which was a huge relief for her. There was nothing special in the letter to be fair, I was just asking them to broadcast some specific songs because all of them were banned in the Soviet Union. I understand why my mother was so afraid. We could have been evicted from the town for being disloyal, my parents could have lost their jobs; we could have lost our home.”

Photo: Isolde Drobina, exclusively for Novaya Gazeta. Europe

Kazakov’s interest in politics aroused in March 1985 when Mikhail Gorbachev became the leader of the Soviet Union. “He appeared to be a normal, living person, unlike his predecessors,” Kazakov says. Gorbachev supported the freedom of expression and transparency, which was very surprising at that time.

Yekaterinburg saw its first political rallies in 1987. In the meantime, a so-called “Voters’ Club” was introduced in Kazakov’s native Novouralsk. Kazakov was a prominent political activist back then. Later, the Soviet Union made amendments to its Constitution, abolishing the Communist Party’s monopoly, shortly before its collapse in December 1991. Kazakov, alongside his fellow activists, called upon Boris Yeltsin, who hailed from the same region and later became Russia’s first president, to put an end to the Soviet regime. They also demanded a Nuremberg-like trial against the Soviet Communist Party.

Gramps Behind Bars

Viktor Kazakov retired in 2012. He has been actively protesting since 2014, often in support of his native region’s natural environment.

“A close friend of mine once told me not to be afraid of anything as I was defending the Earth, our Lord’s creation,” Kazakov explains his firmness against political oppression.

The local police first visited his family house in 2018 when Viktor called for boycott of the Russian presidential election. He glued posters all around the town calling to ignore the election, and when he came home, his family said people from the criminal police had been looking for him. They said Kazakov’s neighbours complained about his family making noise at night, which sure was a decent reason for detectives to be involved. The district police officer and an investigator visited Kazakov in the evening and took him to the police station.

“My family followed me and supported me all the way to the station,” Kazakov recalls. “It was different back then. One could demand that their rights be respected. They didn’t, however, let any of my family inside. They filed a simple administrative offence report against me for urging others to boycott the election, as if I would hide from them in a closed town.”

Viktor’s protests were more or less undisturbed from then on — up until 24 February 2022.

“I had a feeling of an upcoming trouble the day before [the War began]. I was hoping that this would resolve peacefully, but I haven’t been able to sleep at night since then,” Viktor says. How come people die and suffer and you can’t even protest against it?”

Viktor Kazakov in a single picket. Photo from personal archive

On that day, Viktor called Gennady Lomakov, a friend of his, and told him he could not help but take to the streets. He bought some drawing paper, some paint, and created an anti-war poster. All reports filed against Kazakov mention that he created the poster himself.

Kazakov went for a solo protest on 27 February; and Lomakov took a picture of him holding the poster. The two were detained a minute later; they were surrounded so that Viktor’s poster would be not visible by other people in the street.

A woman passing by tried to defend the men: “Leave them alone, they are doing the right thing! Our foolish president started this war.” Kazakov and Lomakov were taken to the police station. The officers on duty told them they had received a report template from a senior Yekaterinburg officer that they had been asked to use against protesters, with a blank space left to be filled with a detainee’s name.

The men were fined 3,000 rubles (€50) each for an “unauthorised rally.” The indented solo protest was declared a rally since two men were present at the scene. This is how Viktor and Gennady became “brothers in crime.”

“Later, someone reported us to the police for ‘discrediting the Russian army’ in my blog,” Viktor says. “We were sentenced to spend nine days in a detention centre. They took us to the courthouse the next day. They would tie us to each other with a pair of handcuffs as if we were some hardcore criminals. Gennady barely made it into the police van. He used to be a pro athlete in the past and now his hip joints are causing all sorts of problems. So, we got into the police van somehow and were taken to the courthouse. They fined us 40,000 rubles (€670) each and took us back to the detention centre.”

Gennady Lomakov in a paddy wagon. Photo from personal archive

Checking the Stitches

“We were put in separate cells like partners in crime,” Viktor is being sarcastic. “There was a guy in my cell who was arrested for violating his probation. He would always say: “Look, I’m 36 years old, and I’ve already spent 13 years in prison.” There was another guy in my cell, a shoplifter who would steal beverages and food from supermarkets. He was visiting our town; said he steals in large quantities and then sells to a different shop at a cheap rate. Like he would sell a huge salami sausage for 100 rubles (€1.70). He boasted that he could steal 40 huge salami sausages in one go. So, this is what he does for a living. There was one more guy in our cell who had his fingernails painted black. He refused to tell us what he was in for and said his name was Grigory Rasputin. We all spoke about politics a lot. The lads were aware that something was wrong about our country, they could easily tell a lie from the truth. We used to listen to the radio a lot and discuss things. They said I helped them understand what was really going on. I think these people are much more humane than those in charge of our country.”

Later on, someone from the local Civic Chamber accused Kazakov and Lomakov of drawing a “rebellious” anti-war graffiti. Neither of them did it, in fact, Kazakov simply took a picture of it earlier.

A policeman visited the two in the detention centre hours before their release; he was wondering if they were the ones who created the graffiti. Kazakov and Lomakov told him they were actually more into drawing posters, not graffitis.

“We’re helping them to boost figures, unfortunately,” Viktor says regretfully. “My lawyer says there are lots of offenders like us in Yekaterinburg, but it’s totally different in other settlements. Here, we are but two crazy old-timers who ruin the whole image of a loyal closed town. This is why they are trying to shut us up.”

Photo from personal archive

Kazakov was later detained again for taking pictures of a pro-war rally. The police considered this an offence against the state and demanded that Kazakov delete all the pictures. They were specifically furious about a picture where the rally was moving next to a bus stop with the words “No to War” written on it.

“They told me I wrote it. They said they would prove that I did this, told me the court was rigged, said it would do as they say,” Kazakov complains. “They speak about things like that openly, but only after they search me and make sure I don’t have a voice recorder on. They would search every stitch of my clothes to be on the safe side. They firmly believe that I’m ‘working for someone,’ they struggle to understand that one may have an opinion different from the crowd. I’m trying to mock them sometimes. “Yes officer, I’m working for the Capitol Hill, you got me,” this is what I say to keep their world view intact.”

Kazakov was detained again on 9 May. He walked the street of his town, taking pictures of the Victory Day military display. Viktor was taken to the police station without any declared reason and searched again.

“First they made sure I had no voice recorder on me, and then they threatened to put me behind bars simply for walking around with a camera,” Viktor says. “They used so much foul language, horrible. They are state officials after all. They demanded that I delete all my blog posts published since 24 February. Actually, I had thought about doing this before they threatened me, thought I might write some things for myself and publish it later. My family also asked me to delete those posts. The police promised to put me behind bars for 15 days and then file criminal charges against me. So, I gave in, and now I’m sick at heart, wondering if I did the right thing. It looks like I betrayed myself, doesn’t it? I might as well go to prison, but this will keep me from capturing what is going on in my town. It turned out, however, that negotiating with the police was a stupid thing to do. They filed another report regarding my posts just as I spoke to them.”

Dzerzhinsky’s Portrait

“I was first taken to the FSB office in 2018 after I reacted fiercely to some of Putin’s words. He said that should a nuclear war happen, Russians would go to heaven, while others would simply drop dead,” Kazakov recalls. “I was outraged. I was wondering if we were threatening the world with starting a nuclear war. So, I had a long talk with the FSB, but they didn’t file any charges against me. They took some notes about me, I guess. There was one thing I noticed when I was there. There was no portrait of Putin on the wall, only Dzerzhinsky’s (Felix Dzerzhinsky was the founder of the Soviet secret police — translator’s note). I asked them if I could take a picture of the portrait, they said I could not.”

Photo: Novaya Gazeta Europe

Today the police detain Kazakov in the blink of an eye when he raises his poster in the street. It was easier back in 2014, however, although sometimes passers-by would attack and insult him, some would even try to snatch a poster out of his hands.

“I don’t blame them,” Viktor says. “I never call them ‘vatniks’ or whatever. I always think of the Germans in the 1930s. People are the same everywhere. Propaganda poisoning is a disease, not a vice. People are getting turned into degenerate monsters against their will. But I also think that those in charge of propaganda are worse than pedophiles. I listened to radio Russia a lot during those nine days in the detention centre. I feel sorry for the people who listen to it, to be fair. Most of my friends are trying to stay away from me, just like the Soviet people did. No one called me to express their support, even my long-time friends. I think they are afraid. I don’t blame them, they probably have reasons for that.”

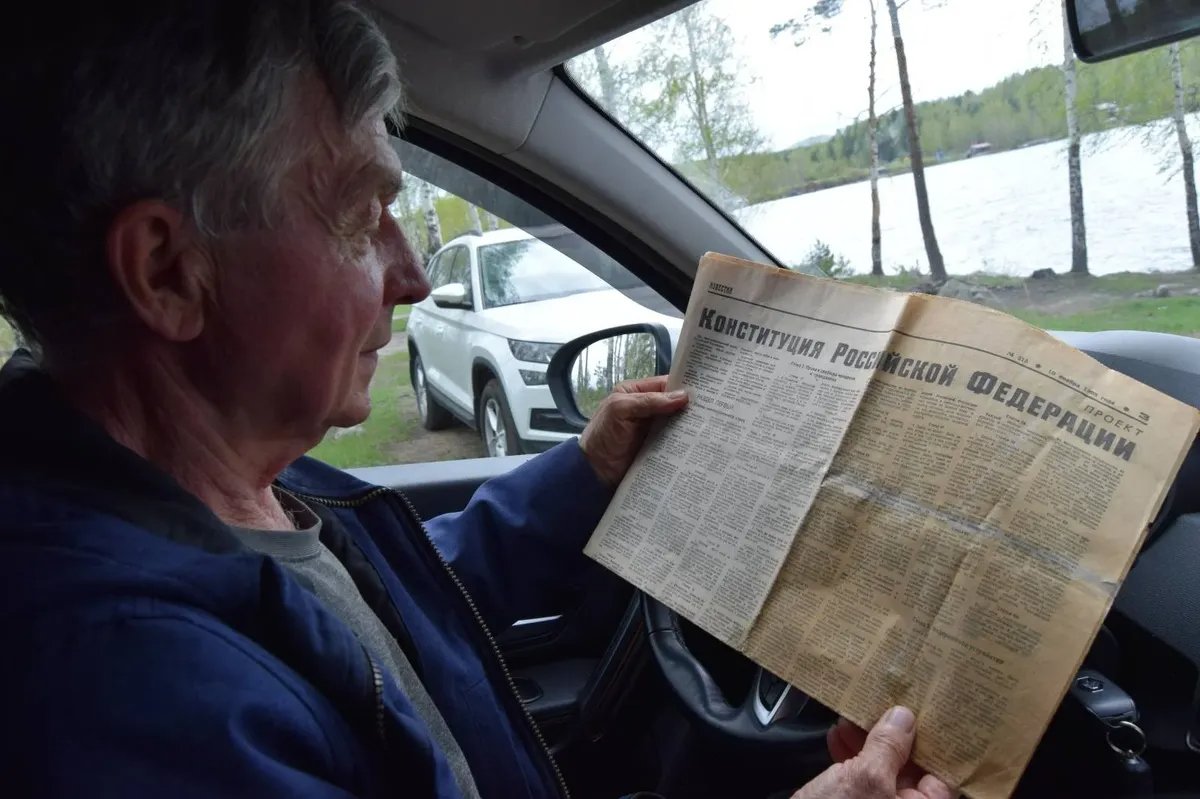

Viktor unwraps and old newspaper from the early 1990s as we are nearing the end of our talk. The newspaper cites a project of the future Russian Constitution. Viktor reads the lines mournfully aloud: “The People, their rights and freedoms are the supreme value. Everyone shall be guaranteed the freedom of ideas and speech. The propaganda of social, racial, national, religious or linguistic supremacy shall be banned.” Viktor barely holds his tears as he reads the paper. He admits he read this paper with great hope back in the day.

“I fought the Soviet regime back when I was young and now it has started all over again,” Viktor sums up. “I mean, it’s nothing on a scale of history, of course. But I’ve spent my entire life here, and I only have one. Still, I believe the good will eventually defeat the evil.”

P.S.

Viktor has had five reports filed against him for “unauthorised rallies” and “discrediting the Russian army” up to date.