Flagship Russian boot brand Faraday has become a Russian manufacturing success story despite the country’s severe sanctioning by the West. Somehow, despite its contracts to supply the Russian military fighting in Ukraine, Faraday’s owners remain unsanctioned, and continue to enjoy access to European markets as well as the freedom to travel there.

Svetlana and Oleg Andrianov have spent much of the past 30 years building their successful family business in Russia from the ground up, having created a boot brand marketed for outdoor activities and the military. The couple currently employs over 1,000 staff in their two factories, which produce 5 million pairs of boots annually.

For several years, Faraday was the sole supplier of boots to the Interior Ministry and the Russian National Guard, and the company’s business model has always focused on winning government contracts.

While it is common practice for manufacturers to drastically slash prices to win contracts, often at the expense of quality, the Andrianovs chose a different path, and have developed a reputation for refusing to compromise on the quality of their products, even when this has meant losing out to other Russian companies for government contracts.

Unsanctioned growth

The war in Ukraine does’t appear to have impacted Faraday as much as you might expect. Shortly after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Faraday’s public VK account published several anti-war posts, which were quickly deleted, as the company claimed its account was hacked and apologised for posting “political and extremist content”. This mishap didn’t seem to deter the Russian Defence Ministry from signing contracts with Faraday, whose combat boots were now in high demand.

The details of procurement orders made by Russia’s Defence Ministry have been classified since the beginning of the war, but there is substantial evidence to indicate that Faraday has been supplying footwear to Russian soldiers fighting in Ukraine.

Faraday is listed as a tailor “supplying clothing items” by Voentorg, Russia’s main military supplies retailer, and several mobilised soldiers serving in Ukraine have confirmed to Novaya Europe that Faraday boots were issued to them as standard kit.

Since the start of the war, the company has ramped up production significantly, thanks in part to a favourable loan from Russia’s Industry and Trade Ministry. “This year we’re completely rebuilding, and re-equipping the factory,” Svetlana Andrianova told Vladimir Putin.

Since the start of the war, the company has ramped up production significantly, thanks in part to a favourable loan from Russia’s Industry and Trade Ministry. “This year we’re completely rebuilding, and re-equipping the factory,” Svetlana Andrianova told Vladimir Putin during a Kremlin meeting on industrial development in August 2023.

Faraday’s well-established relationships with prominent global footwear brands have helped it avoid too much fallout from the war in Ukraine on the international market. The only Russian company to incorporate materials such as Gore-Tex membrane and innovations such as the Boa quick lacing system, Faraday has seen itself join the ranks of popular global brands such as Adidas, Camper, Timberland and Patagonia

According to customs data, Faraday has imported 1.2 billion rubles (€12.5 million) worth of goods from Europe — including equipment needed to retrofit its factories — since the war in Ukraine began, as well as textiles and fabrics from Italy and Spain totalling nearly 1 billion rubles (€10.4 million), with purchases ongoing throughout 2023.

Novaya Europe reached out to some of Faraday’s suppliers for comment, including Boa, which is still listed as a partner on Faraday’s website. In its response, Boa said that while they had done business with Faraday in the past, all collaboration between the two companies ended on 7 March 2022.

Life in unfriendly territory

Olga Andrianova, the daughter-in-law of Faraday’s founders, has a studiedly patriotic profile picture on Russian social media network VK, showing her standing proudly in front of a Russian flag. Her Instagram account tells a slightly different story, however, and is where she shares selfies from her frequent trips all over the world, despite the app being banned in Russia.

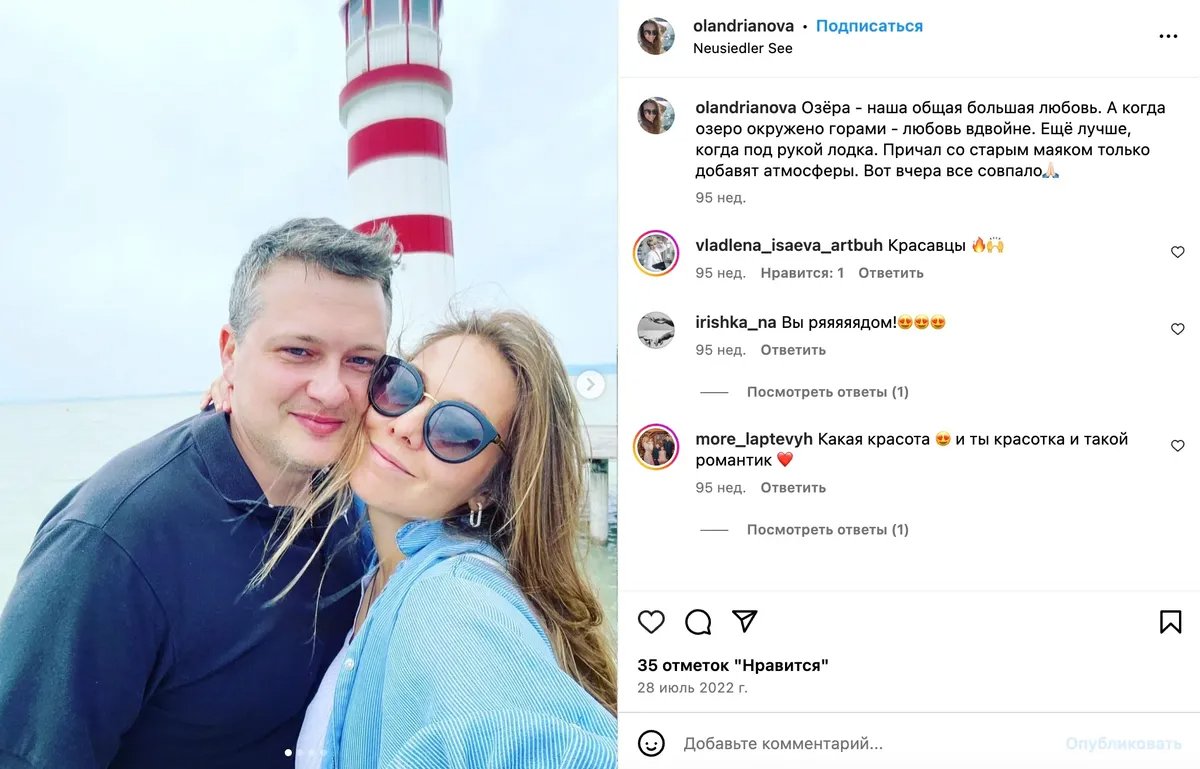

In July 2022, she posted a photo from Slovakia while on a trip to Europe with her husband Alexander near the shore of Lake Neusiedl, a picturesque UNESCO World Heritage site on the border of Slovakia, Austria and Hungary.

A selfie posted on Olga Andrianova’s Instagram account. Screenshot

The Andrianovs’ presence in Slovakia came despite the country imposing a moratorium on issuing visas to Russian citizens following the Kremlin’s decision to invade Ukraine. Slovakia was among the EU countries that declined even to grant humanitarian visas to Russians fleeing mobilisation, but the Andrianovs appear to be an exception.

This is due to the fact that Olga and at least two of their children hold Slovakian citizenship, information leaked from the Russian Interior Ministry’s database confirms.

Novaya Gazeta obtained documents confirming that the family owns several plots of land totalling nearly 30 hectares as well as two houses in the village of Limbach near the capital, Bratislava, an area known to be favoured by wealthy Slovaks.

The family owns a 400 square metre cottage with a large garden and swimming pool where the couple’s children and grandchildren like to spend time during the summer. A second house, spanning 376 square metres, is located a 10-minute walk away.

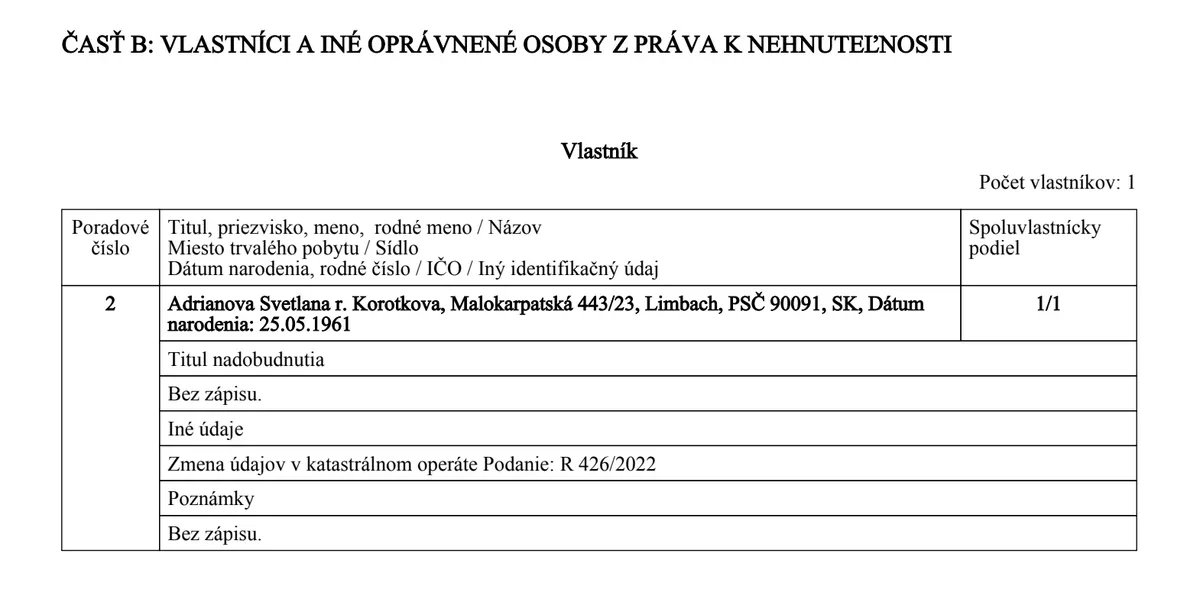

Screenshot from the cadastral register of Slovakia

All of the property is registered to Svetlana Andrianova, who acquired it in 2013. After comparing the registers for 2019 and 2024, Novaya Europe has learned that her last name was changed by one letter after the war started — from Andrianova to Adrianova. All other data, such as year of birth and maiden name, remained the same.

“It cannot be ruled out that this is done to avoid sanctions. Will it really save them from EU sanctions if they want to impose them? I don’t think so,” said Alexander Pomazuev, the head of the sanctions department of the Anti-Corruption Foundation, founded by the late Russian opposition leader Alexey Navalny.

More recently, in April 2023, the family spent a month in Cyprus, where they own another home. In an Instagram story, Olga Andrianova wrote that the family has its own “private beach” where “there is never anyone but us, even during the beach season”.

A photo posted on Olga Andrianova’s Instagram account. Screenshot

The Andrianovs remain free from sanctions even despite their ties to the Russian army, but Pomazuev says campaigning for individual sanctions against them could work in this case.

“I believe that sanctions, when targeted to affect only those benefiting from the war, should be intensified,” Pomazuev said. “This is the beauty of individual sanctions. Random people will not fall under them, and they can be more effectively implemented,” he added.

Campaigning for sanctions helped in the case of Mkrtich Okroyan, the chief designer at the Soyuz aircraft engine research and development complex, who was placed on the sanctions list for his direct links to the production of Russian missiles.

“We had to go and convince people that he had assets, that he should be on the sanctions lists. And to a large extent, this eventually happened because the case was too egregious, because there was a direct link between missiles and assets abroad,” Pomazuev recalled.

“Countless” Russian businessmen who work for the Defence Ministry, like the Andrianovs, end up flying below the radar, Pomazuev lamented.

Still, “countless” Russian businessmen who work for the Defence Ministry, like the Andrianovs, end up flying below the radar, Pomazuev lamented.

Novaya Europe reached out to the European External Action Service, the EU Representation in Slovakia, and the Slovak Interior and Foreign Ministries to ask why Faraday had not been sanctioned, despite supplying equipment to the Russian military. We also asked how EU officials viewed the Andrianov family’s real estate holdings in EU countries and their free movement within the bloc.

Peter Stano, the European External Action Service’s chief representative for foreign affairs and security policy, told Novaya Europe that sanctioning in the EU is an “internal process that is confidential”, which is why EU representatives do not discuss in public how a sanctions decision is made.

Ingrid Ludviková, head of the press team at the Representation of Slovakia in the EU, explained in her response that the sanctions list must be “subject to unanimous approval of all member states”. Ludviková added that such matters fall under the jurisdiction of Slovakia itself rather than the EU as a whole.

Neither the Slovak Interior Ministry nor the Slovak Foreign Ministry responded to Novaya Europe’s enquiries.

Novaya Europe also contacted Oleg and Olga Andrianov to find out what they thought about travelling to “unfriendly countries” during the war. Oleg immediately ended the call upon learning it was a journalist, while Olga listened to the question, hung up, and did not respond to further calls.

Written with the participation of Andrey Serafimov

Join us in rebuilding Novaya Gazeta Europe

The Russian government has banned independent media. We were forced to leave our country in order to keep doing our job, telling our readers about what is going on Russia, Ukraine and Europe.

We will continue fighting against warfare and dictatorship. We believe that freedom of speech is the most efficient antidote against tyranny. Support us financially to help us fight for peace and freedom.

By clicking the Support button, you agree to the processing of your personal data.

To cancel a regular donation, please write to [email protected]